by Yochai Benkler on September 25, 2017

In Why Coase’s Penguin didn’t fly, Henry follows up his response to Cory’s Walkaway by claiming that peer production failed, and arguing that the reason I failed to predict its failure is that I ignored the role of power in my analysis.

Tl;dr: evidence on the success/failure of peer production is much less clear than that, but is not my issue here. Coase’s Penguin and Sharing Nicely were pieces aimed to be internal to mainstream economics to establish the feasibility of social sharing and cooperation as a major modality of production within certain technological conditions; conditions that obtain now. It was not a claim about the necessary success of such practices. Those two economist-oriented papers were embedded in a line of work that put power and struggle over whether this feasible set of practices would in fact come to pass at the center of my analysis. Power in social relations, and how it shapes and is shaped by battles over technical (open/closed), institutional (commons/property), ideological (cooperation/competition//homo economicus/homo socialis), and organizational (peer production & social production vs. hierarchies/markets) systems has been the central subject of my work. The detailed support for this claim is unfortunately highly self-referential, trying to keep myself honest that I am not merely engaged in ex-post self-justification. Apologies. [click to continue…]

by Henry Farrell on July 21, 2017

This is a belated response to Cory’s post on Coase, Benkler and politics, and as such a class of a coda to the Walkaway seminar. It’s also a piece that I’ve been thinking about in outline for a long, long time, in part because of disagreements with Yochai Benkler (who I’ve learned and still learn a ton from, but whom I would like to see address concrete power relations more solidly).

As I said in my own contribution to the seminar, Cory’s arguments in this book are a kind of culmination of what I’ve called BoingBoing socialism – a set of broad ideas exploiting the notion that there is some valuable crossover between the politics of the left and the politics of Silicon Valley. Hence the aim of this post: not to deride that argument, nor to embrace it, but to think more specifically about its possibility conditions. [click to continue…]

by Henry Farrell on May 10, 2017

Cory Doctorow’s new book, _Walkaway_, a novel, an argument and a utopia, all bound up into one, is out. And we’re running a seminar on it. The participants and their posts are all below.

* Andrew Brown is the author of Fishing in Utopia: Sweden and the Future that Disappeared, and a writer and editor at the Guardian. Chatter chatter bang bang.

* Henry Farrell blogs at Crooked Timber. No Exit.

* Maria Farrell blogs at Crooked Timber. Just Meat Following Rules.

* John Holbo blogs at Crooked Timber. The One Body Problem

* Neville Morley is professor of classics and ancient history at Exeter. Free Your Mind (And the Rest Will Follow?)

* Julia Powles is a prolific writer on privacy and technology, and a researcher at Cornell Tech. Walking Away from Hard Problems.

* Eric Rauchway blogs at Crooked Timber. From Scarcity to Abundance.

* Bruce Schneier is the author of Data and Goliath: The Hidden Battles to Collect Your Data and Control Your World, and a cryptographer and public intellectual. The Quick vs the Strong: Commentary on Cory Doctorow’s Walkaway.

* Astra Taylor is author of The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age, a documentary film-maker, and much else besides. Virality is a double-edged sword.

* Belle Waring blogs at Crooked Timber. The Rapture of the Pretty Hip People, Actually.

* Cory Doctorow is Cory Doctorow. Coase’s Spectre

by Cory Doctorow on May 10, 2017

If you’ve read Walkaway (or my other books), you know that I’m not squeamish about taboos, even (especially) my own. I even confess to a certain childish, reactionary pleasure in breaking through them (especially my own!).

But I have a single to-date-inviolable taboo, inculcated into my writerly soul by the elders who nurtured and taught me when I was a baby writer: DON’T RESPOND TO CRITICS. Not when they’re right, especially not when they’re wrong. It never reflects well on you. You can privately gripe to your good friends about unfair criticism (or worse, fair criticism!), but people who don’t like your book don’t like your book and you can’t make them like your book by explaining why they’re wrong, and the spectacle of you doing this will likely convince other people that you’re the kind of fool whose books should not touched with a 3.048m pole.

A corollary, gleaned from the wonderful Steven Brust when I was a baby writer haunting Usenet in the late 1980s: “telling a writer you think his book’s no good is like telling him he’s got an ugly kid. Even if it’s true, the writer did everything he could to prevent it and now it’s too late to do anything about it.”

Rules are made to be broken. These two rules of thumb have served me well in my writerly and readerly life, but a symposium like this is an extraordinary circumstance, a Temporary Autonomous Zone where even the deepest-felt taboos are exploded without mercy. Let us press on, even as my inner compass whirls, unmoored from the norms that were its magnetic north. [click to continue…]

I suppose I should begin by saying few things have ever made me feel as old as this book does; Doctorow’s idea of utopia seems to be something that maybe some kids would like—but I wouldn’t. I’ve no interest in uploading myself and living indefinitely as a meta-stabilized simulation, even if it means downloading myself someday into some new, buff, handsome body. I find it impossible to believe that either the sim or the physique too sexy for its shirts would ever be, in any meaningful sense, me. I don’t just happen to inhabit my body, which is aging and will someday die; I am it—and that is not just okay; that is me.

That aside, let me say that what I take to be the basis for the book is one I find intriguing indeed: how do we navigate the shift from a society premised on scarcity to one premised on abundance? The recent burst of writing on the roboticization of labor has brought home the imminence of an era in which most of us will be economically surplus. Keynes had an idea that the abundant society would be one of leisure and widespread artistic endeavor, one toward which we should aim and for which we should plan; his was a fetching optimism, which appears to have no purchase on the zero-sum, inequality-hugging societies of our time. But abundance, and the values that recognize it, is where Doctorow wants to go—a future in which acquisitiveness might still exist, but is not only no longer laudable, but has become shameful.

Doctorow’s novel envisions a utopia that takes the blogosphere and wikis and other online communities (probably not metafilter though) as the basic model for how an abundant society might organize itself. Physical spaces are as cheaply furnished in his book as virtual ones now are, online. You could live in a world as sleek and spare and instant as a Squarespace site, only less lonely. The key move in establishing such communities is, in Doctorow’s imagined future, turning passive-aggression into a virtue—if someone has screwed up, someone else will just fix it; don’t bother trying to hold the erring party responsible. Doctorow sketches for us these functioning societies formed by walkaways—self-deportees from a reality not unlike our own. These are real-world spaces, as easily pioneered as a new WordPress blog. They would be just as easily infested by trolls, too—but Doctorow seems to think that community norms could quite readily expel such infestations. My own experience of trying to moderate comments sections makes me less optimistic than I take him to be.

Does this sound as though I’m reviewing a philosophical essay, rather than a novel? I hope I’m not being unfair if I say that Doctorow pretty clearly intends this to be a novel of ideas, in which plot and character are secondary to intellectual development. How much you like it will depend on how much you want to turn the ideas over in your head. Doctorow writes of one of his characters, after she is walked through an intellectual thicket, “This discussion killed her horniness.” As the kids say these days, “it me.”

by Neville Morley on May 8, 2017

If the world is burning, and the walls of western civilization are collapsing around our ears, what exactly is the point of devoting time not only to reading speculative fiction – that might be understood, if not necessarily excused, as a temporary escape from contemporary horrors – but to discussing it in a learned manner? Surely our intellectual energies should be focused on the real problems that confront us, not on the imaginary problems of an imagined future? But, the answer may come, of course these are really our problems; extrapolated and magnified and taken to extremes, but still recognisably versions of the issues we face. Still, time is short; surely a more direct engagement with this world is what’s needed, to have any hope of real solutions? [click to continue…]

by Julia Powles on May 4, 2017

Written under the working title Utopia, Cory Doctorow’s Walkaway is billed as a fable of hope in the automated wastelands of the late 21st century. The protagonists are a likeable team of off-grid hackers and makers who have turned their backs on ‘default’, the loveless, jobless plutocratic society run by the ‘zottarich’. As a novel, Walkaway is loose and scrappy, frequently indulging in long, jargon-heavy, mechanical descriptions and smart-ass monologues from characters who all seem to speak the same way. What is perhaps most interesting about the book is in fact what it doesn’t discuss—the unstoppable juggernaut of power, capital and technology that drives today’s digital culture. This matters, because with endorsements from heavy-hitters like Edward Snowden, William Gibson and Neal Stephenson, this book is being boldly pitched as a blueprint for the builders of tomorrow. [click to continue…]

by John Holbo on May 3, 2017

From a Laurie Penny piece last month for The Baffler, “The Slow Confiscation of Everything: How To Think About Climate Apocalypse”: “As David Graeber notes in Debt: The First 5,000 Years, the ideal psychological culture for the current form of calamity capitalism is an apprehension of coming collapse mated bluntly with the possibility of individual escape.”

That’s a Cory Doctorow thought. More specifically, how can humanity defeat the distinctive sorts of bullshit moral self-delusion that are the bastard progeny of that blunt mating? Evil snowcrash of snowflakes, melting, each trying to be The One. Cory credits Graeber (among others) right there on his acknowledgement page. And I might add: Penny immediately mentions Annalee Newitz’ new book, Scatter, Adapt, And Remember: How Humans Will Survive A Mass Extinction – which bears an effusive Doctorow blurb: “… balanced on the knife-edge of disaster and delirious hope.”

Call it the one-body problem. I’ve only got the one, you see …

Meanwhile, what matters is: you know, humanity. [click to continue…]

Seminar on Cory Doctorow’s Walkaway

Recently, someone who works in an adjacent field was described by a friend as having been radicalised. It’s an odd verb, that, radicalised; to be made radical. It sounds almost as if it happens without agency. To have all the depth, complexity and contradiction in your understanding of human life boiled away, leaving the saltiest essence, crystallised on the bottom of a burnt saucepan. That would take some extreme heat, you would think.

Here’s what apparently happened to this guy. He published a book about competition. Part of it looked at search engines. Talking about the book soon after it was published, his tone was, by my friend’s account, pretty even-handed; full of ‘on the one hand, we need new ways of thinking about monopolies that aren’t just based on immediate consumer harm’, and ‘on the other hand, we get lots of nice shiny things from this free – to consumers – service’. But things started happening. Pieces got spiked. When he wrote about the issues, the company would complain, or insist on a right of reply, either directly or via proxies. And when he spoke in public, there was usually a paid stooge in the audience. [click to continue…]

by Belle Waring on May 1, 2017

No spoilers because I’m just talking in generalities. Read away.

Walkaway is a book in which important issues about how we should live, and how we can live, are discussed and hashed out very thoroughly. Not anywhere near the level of Kim Stanley Robinson, when in the course of reading you are inclined to ask, “did I just read 160 pages of minutes from an anarcho-syndicalist collective meeting? Yes, yes I did. Huh. Why I am I finishing this trilogy? Oh right, I have a compulsive need to finish any book.” Nonetheless, the discussions are full and mostly quite satisfying even as they treat difficult issues. What do we owe one another in society? How should we distribute resources? (I will note in passing that there is a certain tension between the post-scarcity economy that seems to be available and the widespread poverty of the “default” world, but we can hardly expect a smooth transition from the one to the other; perhaps this is realism rather than inconsistency.)

However there is one topic which does not get as much of this treatment, in my opinion, even as it is a very live issue in the plot, namely, is a copy of you really you? If your consciousness could be uploaded to a computer and successfully simulated, would this represent a continuation of your actual self, or merely the creation of a copy of you, like an animated xerox? Would you “go on living” in some meaningful sense? What if these new copies of you were drafted as servants, to use the way we use machines now, but a thousand times more useful? [click to continue…]

by Astra Taylor on April 28, 2017

Is Walkaway a novel? The answer is undoubtedly yes, but as long as I thought about it in terms of literature I’ll confess I found the book a bit confounding. Once I re-categorized it in my head as a book of political philosophy, something in the mode of Plato’s dialogues (which even get a couple of shout outs from Doctorow), I was able to accept, and even enjoy, the text in front of me. The long expository and ideologically-focused conversations (all composed in the same rather pedagogic voice no matter which character is speaking) are extremely engaging by the standards of political theory, and there’s plenty of action—sex, violence, raves, and hanging out in saunas—interspersed with the arguments and explications. And the arguments are thought provoking, if not wholly convincing. Which is fine, because it is a novel, after all. [click to continue…]

by Andrew Brown on April 27, 2017

This is a novel of ideas which proceeds through pages of earnest conversation interrupted by cataclysmic explosions or scarcely less cataclysmic fucks after which another set of characters take up another earnest conversation until the next explosion. Chatter chatter bang bang – and this time the magic car is taking us back to the late Sixties. The counterculture in Walkaway is a very recognisable enlargement of the world according to the Whole Earth Catalog, in which technology and computers and spontaneous co-operation will combine to deliver us from evil. You reach the better world by separating from the Evil Big Daddy world through a tunnel of music, sex and drugs and when you have made this journey of rebirth you build the new Jerusalem, a shining Shoreditch on a hill.

Since I am going to be rude about the ideas, it’s worth saying right now that the novel, is much more interesting than the world that it is set in, because the novel has a couple of complex and well realised characters, among them the heroine’s evil father. And the consideration of how you deal with the existential dread of a computer program which realises it’s a human being is science fiction at its best.

But the world in which this utopia is worked out has fatal problems. [click to continue…]

by Bruce Schneier on April 26, 2017

Technological advances change the world. That’s partly because of what they are, but even more because of the social changes they enable. New technologies upend power balances. They give groups new capabilities, increased effectiveness, and new defenses. The Internet decades have been a never-ending series of these upendings. We’ve seen existing industries fall and new industries rise. We’ve seen governments become more powerful in some areas and less in others. We’ve seen the rise of a new form of governance: a multi-stakeholder model where skilled individuals can have more power than multinational corporations or major governments.

Among the many power struggles, there is one type I want to particularly highlight: the battles between the nimble individuals who start using a new technology first, and the slower organizations that come along later. [click to continue…]

by Henry Farrell on April 25, 2017

One of the people who blurbed Walkaway enthusiastically is William Gibson, whose own most recent book, The Peripheral covers many of the same themes that Walkaway does. The rise of extreme inequality described by Piketty and others, as the super-rich become so different from everyone else as nearly to be a distinct species. Accelerating technological change so that there are no jobs, or only very bad ones, for most people. A post-industrial landscape, in which the wreckage of the industrial era provides valuable resources for those in the new era.

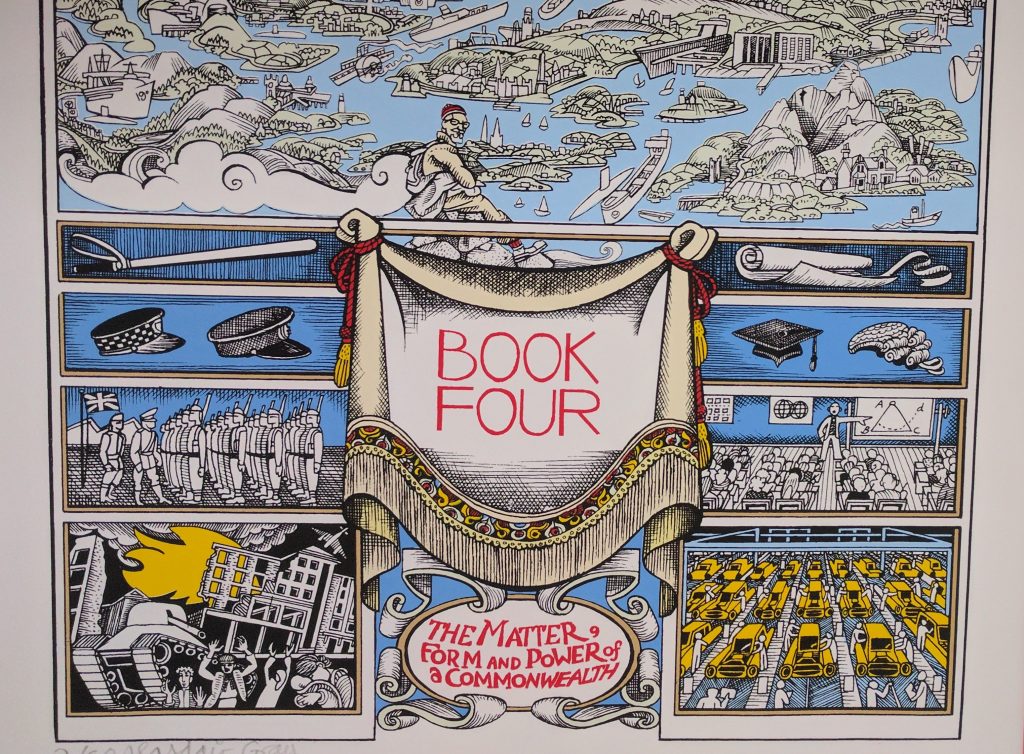

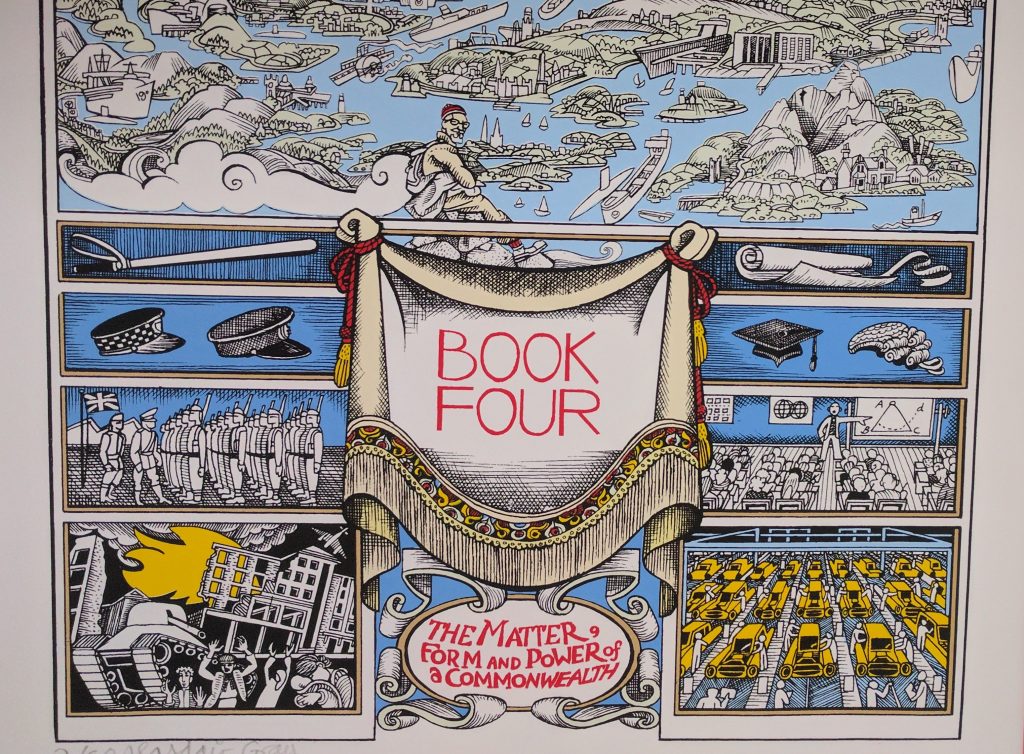

Yet the two books draw radically different conclusions from roughly similar premises. Gibson’s book is a dystopia, in which the rich are so powerful as to be, effectively, beyond challenge. The only possibilities for agency on the part of anyone else are in the interstices, the implied spaces within the structures of the internecine conflicts of the elites. Walkaway, in contrast, is a book about the beginnings of a utopia. The characters frequently quote variants of Alasdair Gray’s dictum that one should “work as if you lived in the early days of a better nation.” Above is a detail from a print by Gray, based on his frontispiece for Book Four of Lanark. It displays the forces through which the state, “foremost of the beasts of earth for pride,” maintains its domination, with the machineries of war to the left, and those of law and thought to the right. At the end of Walkaway, Doctorow’s characters live in a society which appear to have mostly escaped from both kinds of domination. [click to continue…]