I’m surprised that there hasn’t been more discussion outside Europe about the Anglo-Irish tapes. A summary from a “review”:http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/features/2010/1005.farrell.html I did a few years ago of Fintan O’Toole’s book on the Irish collapse.

bq. Anglo Irish Bank —Ireland’s third-largest bank and the most spectacular exemplar of the Celtic Tiger’s flameout— bet its future on loans to well-connected property developers. O’Toole suggests that “[i]t may be an exaggeration to call Anglo Irish a private bank for Fianna Fáil’s more flamboyant friends—but only a small one.” Not only did Anglo Irish itself invest heavily in the property market, but it lent more than 100 million euros to its chairman (as well as smaller sums to other directors) to speculate in property on his own account, and then hid the loan on its balance sheet through sleight of hand. The Central Bank–based regulator charged with regulating financial services knew about both the loans and the cover-up but declined to act. To borrow University College Dublin economist Morgan Kelly’s term, Anglo Irish was “too connected to fail”—no serious regulatory response was possible.

bq. When Anglo Irish began to get into trouble, a “golden circle” of ten investors borrowed money from the bank itself to invest in its own shares and hence keep the share price from tanking. Seventy-five percent of the loans were backed by the shares themselves. Six members of the golden circle are known; most of them have strong Fianna Fáil connections. Anglo Irish executives and board members were also allegedly given loans to buy shares to help “counter negative publicity.”

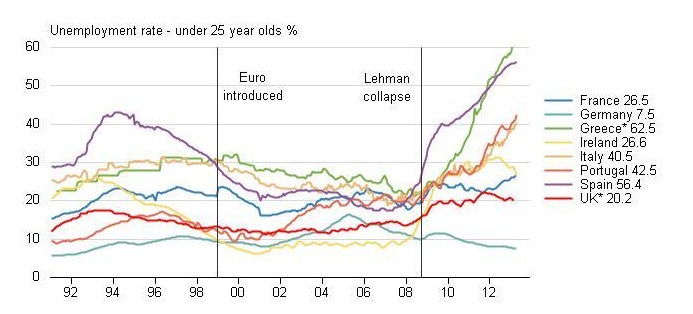

After the failure of Lehmann, Anglo Irish found itself in very serious trouble. The Irish state stepped in first to guarantee the debts of Anglo Irish Bank and other banks, and then to nationalize Anglo Irish. Over the last couple of days, the Irish Independent has been releasing extracts from recorded phone conversations between senior Anglo Irish executives in the lead-up, and they … say interesting things … about the attitude of bailed out bankers. Some of the extracts:

[the problem, as stated to the Irish Central Bank]

bq. To cut a long story short we sort of said. ‘Look, what we need is seven billion euros… what we’re going to give you is our loan collateral so we’re not giving you ECB, we’re giving you the loan clause.

[how the regulator was quoted as responding when he he heard the proposed figure]

bq. Jesus that’s a lot of dosh … Jesus fucking hell and God … well do you know the Central Bank only has €14 billion of total investments so that would be going up 20 … Jesus you’re kind of asking us to play ducks and drakes with the regulations.

[where the 7 billion figure came from]

bq. Just, as Drummer [CEO David Drumm] would say, ‘I picked it out of my arse’.

[why the figure was quoted, even though senior management knew it was inadequate]

bq. That number is seven but the reality is we need more than that. But you know, the strategy here is you pull them [the Central Bank] in, you get them to write a big cheque and they have to keep, they have to support their money, you know.

[response]

bq. They’ve got skin in the game and that’s the key.

[response to the response]

bq. If they saw the enormity of it up front, they might decide they have a choice. You know what I mean? They might say the cost to the taxpayer is too high…if it doesn’t look too big at the outset…if it doesn’t look big, big enough to be important, but not too big that it kind of spoils everything, then, then I think you can have a chance. So I think it can creep up.

bq. So, so … [the €7 billion] is bridged until we can pay you back … which is never. [Loud laughter]”

[when the executives heard that the proposed bailout was causing diplomatic problems with other European states]

bq. So fuckin’ what. Just take it anyway . . . stick the fingers up.”

Also, loud laughter when one executive starts singing “Deutschland Uber Alles” in response to the worry that the saga was causing a rift between Ireland and Germany. As you might imagine, that’s going down a storm with German media.