by Chris Bertram on May 1, 2014

Today is the first of May, a day of international solidarity for the working class and labour movement, and always a day of memory for me. In the mid 1970s when I was thirteen years old, I was sitting with my language exchange partner Pierre in his bedroom in a ground floor flat in Montparnasse. I was leafing through a magazine — Paris Match as it happens — and there were pictures of the May events from 1968. I was absolutely stunned by them. Here, in Western Europe, there had been a street-fighting and a general strike within the past few years? I’d been aware of Czechoslovakia and, indeed, my whole school had chanted “Dubcek! Dubcek!” when the Christmas pudding had been brought out in 68, but of Paris I knew nothing. I resolved to find out more, and when the opportunity arose to choose a school history project, I asked if I could study the May events and produced a longish dossier, complete with photos, newspaper clippings and the rest. A few years later, in 1978 — and hence on the 10th anniversary — I joined the May Day parade for myself at the Place de la République, no longer an observer but a participant.

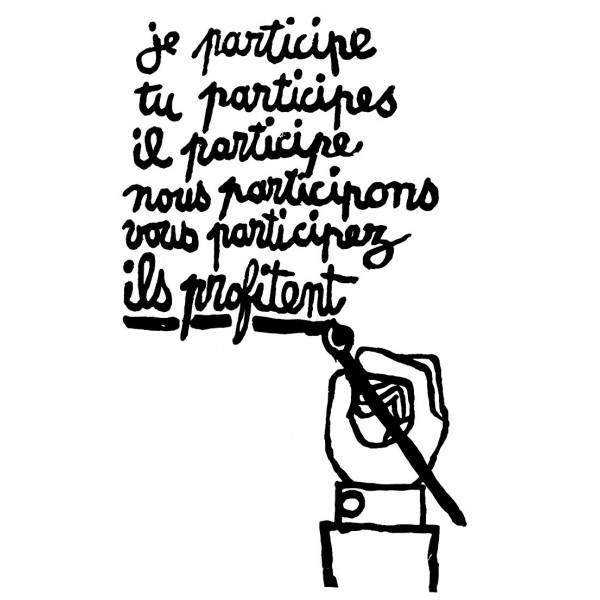

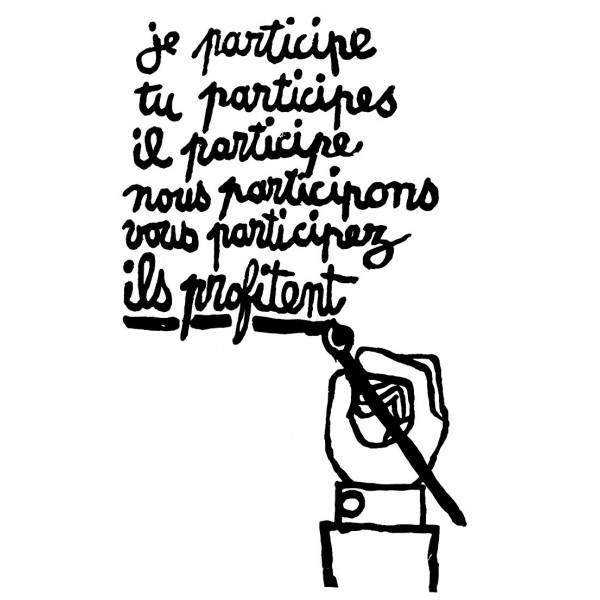

What did May represent for me? There was an element of romantic adolescent attachment to be sure, but also the possibility of another society. In the reconstructed history of the victorious Thatcherites the choice that had to be made was between the marketized West and the gloomy authoritarianism of the Soviet bloc. But May 68 seemed to offer a different way, perhaps (oh dear!) a third way. And in a sense it did, it offered the hope of a non-authoritarian and participatory egalitarianism (and coupled with the Prague Spring, the chance of socialism with a human face). From that flowed a lot of other things, social movements, feminism, ecologism, trends in art and culture (there were other sources for these streams, to be sure). The possibility of rejecting the world of corporate power without embracing dourness and concrete was a liberating thought, some might say a naive and romantic one, to which I say “Soyez réaliste, demandez l’impossible!”

The memory of May, or at least the memory of the possibility of May, has always been there for me as a nourishing idea like Wordsworth’s Tintern when times have been bad (as they so often have since). It doesn’t have to be this way: vivre autrement. Sadly, when I was talking to a very smart student of left-wing convictions the other day, I mentioned May 68 and she asked “What happened in May 68?” It seems the memory of May is no longer there in the imagination of the left. Time for a revival.

by Corey Robin on May 1, 2014

In The Empire of Necessity, Greg Grandin gives us a fascinating history of the phrase “to strike.” Seems like a good story for May Day.

The phrase to strike to refer to a labor stoppage comes from maritime history and is an example of how revolutionary times can redefine a word to mean its exact opposite. Through the seventeenth and much of the eighteenth century, to strike was used as a metaphor for submission, referring to the practice of captured ships dropping, or striking, their sails to their conquerors and of subordinate ships doing the same to salute their superiors. “Now Margaret / must strike her sail,” wrote William Shakespeare in Henry VI, describing an invitation extended by the “Mighty King” of France to Margaret, the weaker Queen of England, to join him at the dinner table “and learn a while to serve / where kings command.” Or as this 1712 account of a British privateer taking a Spanish man-o’war off the coast of Peru put it: “fir’d two shot over her, and then she struck,” and bowed “down to us.” But in 1768, London sailors turned the term inside out. Joining city artisans and tradesmen—weavers, hatters, sawyers, glass-grinders, and coal heavers—in the fight for better wages, they struck their sails and paralyzed the city’s commerce. They “unmanned or otherwise prevented from sailing every ship in the Thames.” From this point forward, strike meant the refusal of submission.

Not unlike how gays and lesbians owned the word “queer.”

by Eszter Hargittai on May 1, 2014

Janet Vertesi decided that she didn’t want companies and marketers to know that she was pregnant. How hard is that nowadays in the US with so little data privacy protection for consumers? It turns out it’s quite complicated. Not only does it result in lots of inconveniences such as seeming rude to family and friends or having to concoct complicated ways of purchasing things, but it may even make you look like a criminal. Reading about her experiences is thought provoking. She certainly does a good job challenging the idea that not being tracked is as simple as opting out through some simple clicks of a button. While those who think about these issues are well aware of that, many people are not as some of her examples show.

by John Holbo on May 1, 2014

For the last month or so ‘political correctness’ – the term – has been bugging me. Perhaps there’s been a slight uptick in usage on conservative sites and blogs, due to some combination of Cliven Bundy, Brendan Eich and Donald Sterling. But really the problem is chronic.

Why did ‘political correctness’, which is so … Dinesh D’Souza circa 1991 … become an evergreen right-wing complaint? [click to continue…]