The efforts of the right to discredit Piketty’s Capital have so far ranged from unconvincing to risible (Chris picked up a particularly amusing one from Max Hastings in the Daily Mail, to which I won’t bother linking). One point raised in this four-para summary by the Economist is that ” today’s super-rich mostly come by their wealth through work, rather than via inheritance.” Piketty does a good job of rebutting this, but for those who haven’t acquired the book or got around to reading it, I thought I’d repost my own response, from 2012.

From the monthly archives:

May 2014

Matthew Yglesias, responding to Tyler Cowen and my critique of same.

high levels of income inequality lead to high prices for art. A lot of this reflects higher prices for old paintings by dead artists, but the art market exhibits sufficient efficiency that higher prices also benefit new works by living artists. … The mechanism, basically, is that art-buying is mostly done by very rich people so when very rich people get richer, the price of art gets bid up. When buying power shifts to the middle class they tend to buy more banal things like bigger houses or nicer cars.

Whether these price trends are good for the arts is going to depend on a bunch of other questions that the paper doesn’t address. Do higher prices for art works induce artists to become more productive? Does greater output come at the expense of quality? Do people shift into painting from more mass market artistic pursuits (music, movies) or from careers outside the arts? Do higher prices make art less accessible to non-rich art lovers? One can imagine a whole range of different outcomes here. But the evidence that inequality boosts the financial returns to the fine arts — largely by diverting financial resources away from middle class consumption of normal stuff — seems compelling.

By coincidence, I’ve recently finished reading The People’s Platform, Astra Taylor’s wonderful new book on culture and the Internet (Amazon, Powells), which gives a much more jaundiced account of what is happening to art in the age of inequality (see here for an interview which gives some flavor of her thinking). [click to continue…]

In addition to Kieran’s terrific write-up yesterday on Foucault’s engagement with Gary Becker, I want to recommend Kathy Geier’s very smart treatment of, among other things, feminist critiques of Becker’s theory of the family.

There are many ideas in Becker’s Treatise on the Family (originally published in 1981; republished in a revised version in 1991) that are problematic and/or offensive to feminists. For one thing, there is the assumption that economic actors behave selfishly in markets but altruistically within families — a theory that’s objectionable in both parts. There’s also the matter of how, in the words of Deirdre McCloskey, “the family in Becker’s world has one purpose, one utility function — guess whose? — unproblematically unified in the way that the neoclassical firm is supposed to be.” [click to continue…]

Gary Becker, University Professor of Economics and Sociology at the University of Chicago, has died at the age of eighty three. I am certainly not going to attempt an obituary or assessment. But something Tim Carmody [said on Twitter](https://twitter.com/tcarmody/status/463022768209285120) caught my eye: “People sometimes talk about ‘neoliberalism’ as a kind of intellectual bogeyman. Gary Becker was the actual guy.” In a somewhat similar way, people sometimes talked about ‘poststructuralism’ as a kind of intellectual bogeyman, and Michel Foucault was the actual guy. It is worth looking at what one avatar had to say about the other. Foucault [lectured on Becker and related matters in the late 1970s](http://www.amazon.com/The-Birth-Biopolitics-Lectures-1978–1979/dp/0312203411/). One of the things he saw right away was the scope and ambition of Becker’s project, and the conceptual turn—accompanying wider social changes—which would enable economics to become not just a topic of study, like geology or English literature, but rather an “[approach to human behavior](http://www.amazon.com/The-Economic-Approach-Human-Behavior/dp/0226041123)”. Here is Foucault in March of 1979, for instance:

> In practice, economic analysis, from Adam Smith to the beginning of the twentieth century, broadly speaking takes as its object the study of the mechanisms of production, the mechanisms of exchange, and the data of consumption within a given social structure, along with the interconnections between these three mechanisms. Now, for the neo-liberals, economic analysis should not consist in the study of these mechanisms, but in the nature and consequences of what they call substitutible choices … In this they return to, or rather put to work, a defintion [from Lionel Robbins] … ‘Economics is the science of human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses’. … Economics is not therefore the analysis of the historical logic of processes [like capital, investment, and production]; it is the analysis of the internal rationality, the strategic programming of individuals’ activity.

Then comes the identification not just of the shift in emphasis but also point of view:

> This means undertaking the economic analysis of labor. What does bringing labor back into economic analysis mean? It does not mean knowing where labor is situated between, let’s say, capital and production. The problem of bringing labor back into the field of economic analysis … is how the person who works uses the means available to him. … What system of choice and rationality does the activity of work conform to? … So we adopt the point of view of the worker and, for the first time, ensure that the worker is not present in the economic analysis as an object—the object of supply and demand in the form of labor power—but as an active economic subject.

I like this song (“Tous les Mêmes” [corrected, thanks Ezster!]) and video by Belgian musician Stromae. I hope you will also.

I am distracted from his alternate blue-green-male/magenta-female personalities by the fabulous furniture in their apartment. Probably my job has gotten to me too much if my immediate thought is “I want that wall-mounted storage unit!” rather than “this reminds me of when I wondered where they got all those implausibly tall, thin dudes to dance on Soul Train, and whether it was just because cocaine is one helluva drug, or what–no, here’s Stromae!” (I grant there’s a hidden premise.) Tertiary May Day thought inspired by outdoor dance scene: I always read that students were throwing cobblestones, and then I ever saw any and thought, “that must have took a damn bit of effort to get up out the ground.” Also I stepped on Eszter’s post. Sorry!

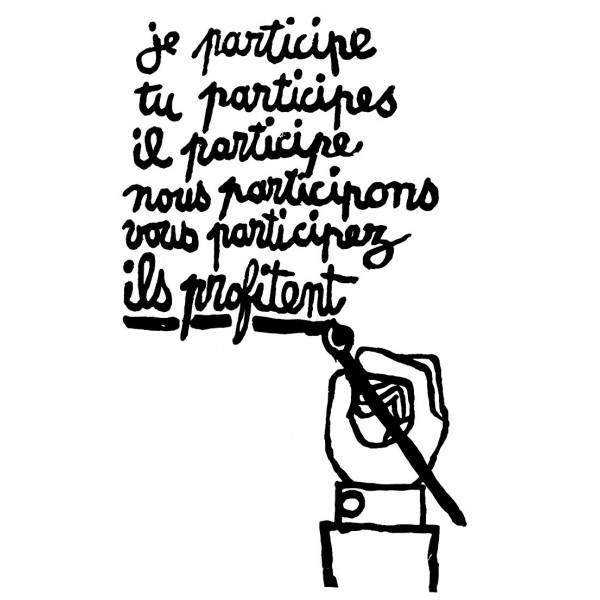

Today is the first of May, a day of international solidarity for the working class and labour movement, and always a day of memory for me. In the mid 1970s when I was thirteen years old, I was sitting with my language exchange partner Pierre in his bedroom in a ground floor flat in Montparnasse. I was leafing through a magazine — Paris Match as it happens — and there were pictures of the May events from 1968. I was absolutely stunned by them. Here, in Western Europe, there had been a street-fighting and a general strike within the past few years? I’d been aware of Czechoslovakia and, indeed, my whole school had chanted “Dubcek! Dubcek!” when the Christmas pudding had been brought out in 68, but of Paris I knew nothing. I resolved to find out more, and when the opportunity arose to choose a school history project, I asked if I could study the May events and produced a longish dossier, complete with photos, newspaper clippings and the rest. A few years later, in 1978 — and hence on the 10th anniversary — I joined the May Day parade for myself at the Place de la République, no longer an observer but a participant.

What did May represent for me? There was an element of romantic adolescent attachment to be sure, but also the possibility of another society. In the reconstructed history of the victorious Thatcherites the choice that had to be made was between the marketized West and the gloomy authoritarianism of the Soviet bloc. But May 68 seemed to offer a different way, perhaps (oh dear!) a third way. And in a sense it did, it offered the hope of a non-authoritarian and participatory egalitarianism (and coupled with the Prague Spring, the chance of socialism with a human face). From that flowed a lot of other things, social movements, feminism, ecologism, trends in art and culture (there were other sources for these streams, to be sure). The possibility of rejecting the world of corporate power without embracing dourness and concrete was a liberating thought, some might say a naive and romantic one, to which I say “Soyez réaliste, demandez l’impossible!”

The memory of May, or at least the memory of the possibility of May, has always been there for me as a nourishing idea like Wordsworth’s Tintern when times have been bad (as they so often have since). It doesn’t have to be this way: vivre autrement. Sadly, when I was talking to a very smart student of left-wing convictions the other day, I mentioned May 68 and she asked “What happened in May 68?” It seems the memory of May is no longer there in the imagination of the left. Time for a revival.

In The Empire of Necessity, Greg Grandin gives us a fascinating history of the phrase “to strike.” Seems like a good story for May Day.

The phrase to strike to refer to a labor stoppage comes from maritime history and is an example of how revolutionary times can redefine a word to mean its exact opposite. Through the seventeenth and much of the eighteenth century, to strike was used as a metaphor for submission, referring to the practice of captured ships dropping, or striking, their sails to their conquerors and of subordinate ships doing the same to salute their superiors. “Now Margaret / must strike her sail,” wrote William Shakespeare in Henry VI, describing an invitation extended by the “Mighty King” of France to Margaret, the weaker Queen of England, to join him at the dinner table “and learn a while to serve / where kings command.” Or as this 1712 account of a British privateer taking a Spanish man-o’war off the coast of Peru put it: “fir’d two shot over her, and then she struck,” and bowed “down to us.” But in 1768, London sailors turned the term inside out. Joining city artisans and tradesmen—weavers, hatters, sawyers, glass-grinders, and coal heavers—in the fight for better wages, they struck their sails and paralyzed the city’s commerce. They “unmanned or otherwise prevented from sailing every ship in the Thames.” From this point forward, strike meant the refusal of submission.

Not unlike how gays and lesbians owned the word “queer.”

Janet Vertesi decided that she didn’t want companies and marketers to know that she was pregnant. How hard is that nowadays in the US with so little data privacy protection for consumers? It turns out it’s quite complicated. Not only does it result in lots of inconveniences such as seeming rude to family and friends or having to concoct complicated ways of purchasing things, but it may even make you look like a criminal. Reading about her experiences is thought provoking. She certainly does a good job challenging the idea that not being tracked is as simple as opting out through some simple clicks of a button. While those who think about these issues are well aware of that, many people are not as some of her examples show.

For the last month or so ‘political correctness’ – the term – has been bugging me. Perhaps there’s been a slight uptick in usage on conservative sites and blogs, due to some combination of Cliven Bundy, Brendan Eich and Donald Sterling. But really the problem is chronic.

Why did ‘political correctness’, which is so … Dinesh D’Souza circa 1991 … become an evergreen right-wing complaint? [click to continue…]