I love writing. The medium is excellent for communicating ideas, or a narrative history. But writing is one-dimensional, and it’s much worse at communicating the history of ideas in higher dimensions.

My meta-scientific interest in understanding how ideas travel, how their fate waxes and wanes, has frequently pushed me beyond my preferred medium. Traditional historiography is extremely time-consuming: you have to read and compare various histories of the same topic over time and across perspectives.

An inductive, data-driven approach won’t provide any conclusive results — but it might tell us where we should look. My goal is to find ideas that at one point seemed promising—perhaps, with modern technology, we can explore branches of human development that were prematurely or arbitrarily cut off. The cybernetic socialism of Stafford Beer is one of my favorite such examples; what else can we find?

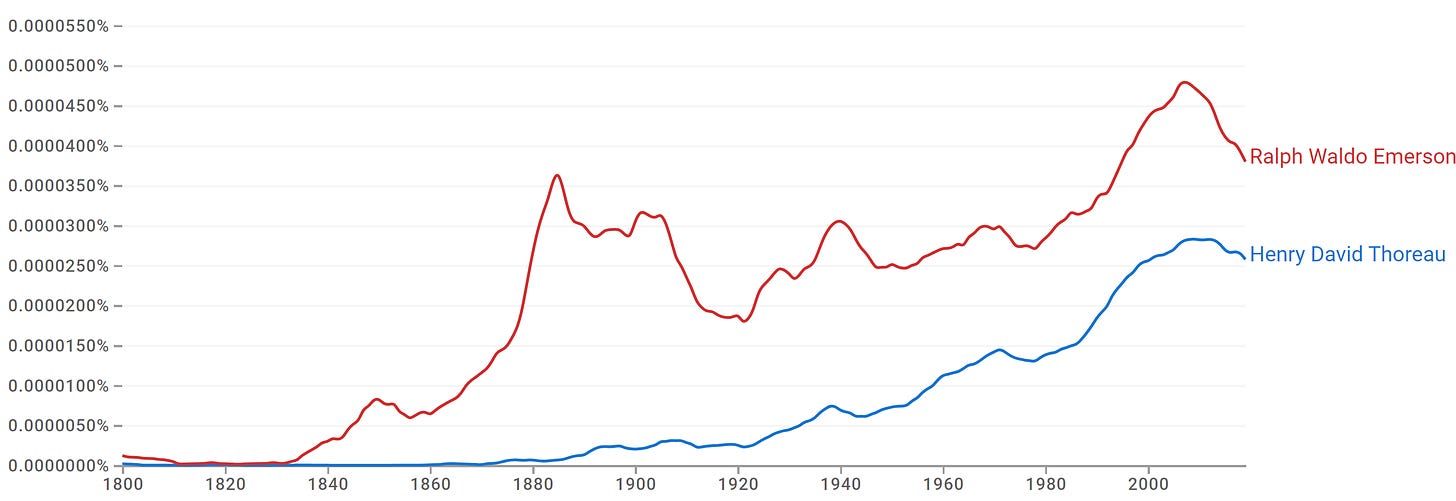

Every American high schooler learns about the twin giants of Transcendentalism: Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. The two most famous members of the Transcendentalist Club, with contrasting vibes, make for a neat narrative. But the data tell a different story.

Emerson has long been an important figure in the history of ideas, but nobody gave a fuck about Thoreau for decades after his death. Poking around a bit, my take is that his anti-war sentiment caused an uptick in interest in the 1940s, and then again in the 1960s and 70s, when the hippies found broader resonance with his more poetic writing. The subsequent elevation is precisely the consequence of the narrative crafted for the high school US History class that prompted me to think of this comparison in the first place. And then there’s the worst fanfic of all time, Walden Two, on which more, later.

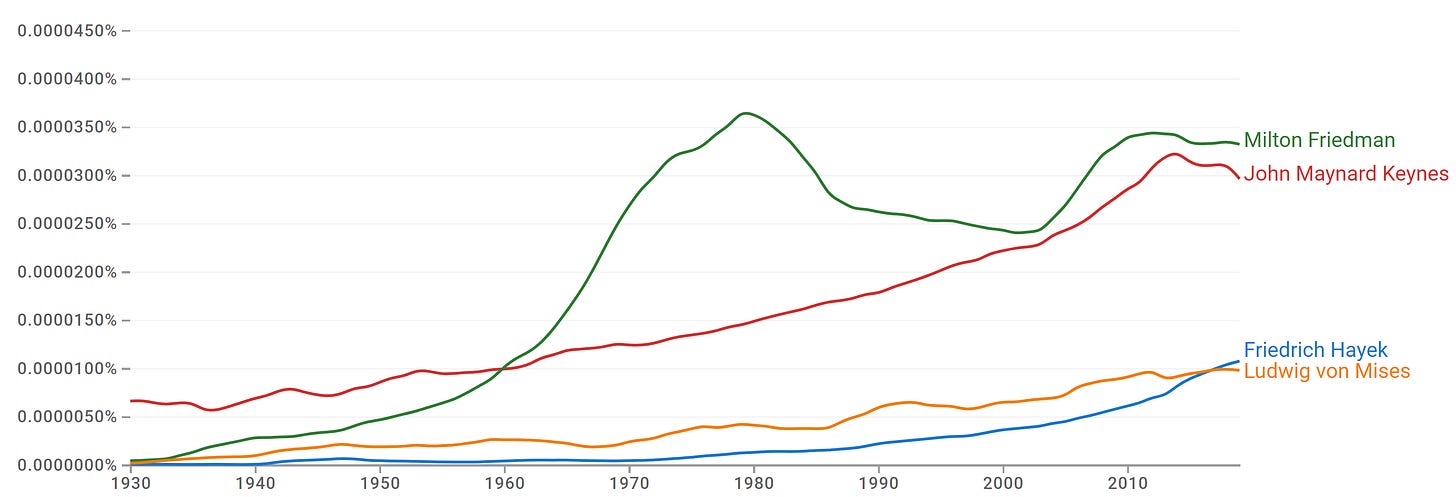

Another example, from Economics. The major axis of debate over the past century has been between the pro-market and pro-state intervention camps, and their respective champions Friedrich Hayek and John Maynard Keynes. Except that…Hayek was an inside job.

Nobody was talking about him (in the English-language books indexed by Google Ngrams) until the 1970s, and there has been a noted slope change in interest in the 2010s. Fellow free-marketer Milton Friedman has always been more important, and even fellow Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises had more coverage until very recently.

Proper nouns like this are a powerful historiographical tool because they’re fixed. Concepts like “democracy” or “feminism” are far less amenable to this method because their meaning shifts over time. We don’t really care about the words except insofar as they refer to the same underlying idea. But proper nouns point to the same person; especially after they die, their referent is fixed, and we can learn about the intellectual context by looking at trends in their use.

Haha. If only it were that simple.

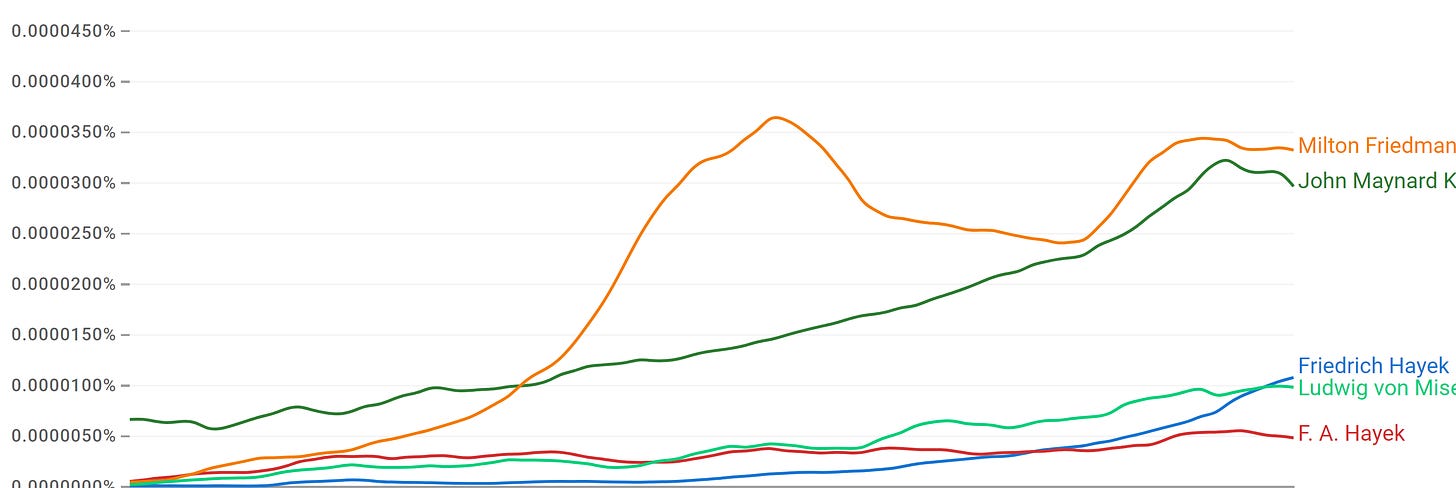

In his lifetime, the anglophile Hayek more often went by “F. A. Hayek” rather than his Germanic given name, which complicates the data-historiographical story. Hayek was important, especially in the 1940s and 50s after publishing The Road to Serfdom. Adding the two lines together makes his case look more like Keynes’, though the sharp uptick over the past decade is still striking.

The Hayek example also casts doubt on the data-historiographical method. I had the contextual knowledge to check for this — a purely machine-driven approach would have a much more difficult time matching these records. The Google Ngrams interface is especially finicky, so I’d take any of these results as preliminary.

(Methodological aside: this problem calls out for some heavy inductive machine learning. Large, comprehensive datasets like the Ngrams corpus or longitudinal surveys like the Census’ American Communities Survey and the political scientists’ American National Election Survey would benefit tremendously from this kind of pre-processing. Current practice entails taking the dataset as given and asking each researcher to preform their own ad hoc data manipulations, a recipe for duplicated efforts, false positives and outright error.)

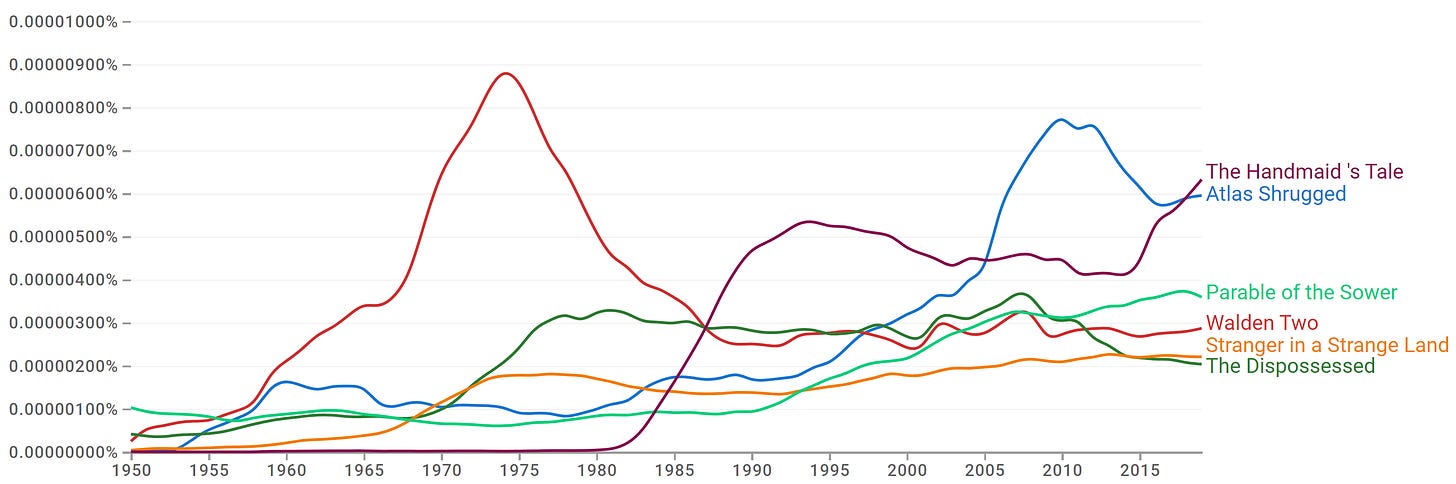

An even more fixed kind of proper noun is that reinforced by copyright law. For intellectual history, the best example is the book. Science fiction is an excellent resource for understanding a society’s fantasies and fears, its vision of possible futures. Or, in the case of Atlas Shrugged, its vision of possible futures foregone.

The Randian masterpiece exploded in popularity in the early 200s, and has since fallen off. The Dispossessed, Ursula Leguin’s ambivalent socialist novel, held steady for four decades before seeing a recent decline in interest. In contrast, Parable of the Sower and The Handmaid’s Tale have seen gradual and sharp growth, respectively. (These two examples also complicate the proper noun story. The former is, of course, named after a parable that appears in the Gospels; the latter recently became a television series.)

The real story here is Walden Two, which in 1975 was more popular than Atlas Shrugged ever was, but which few people today have heard of. This is just as well. This book sucks ass. I picked up a used copy, read it, and then physically destroyed it, I was so upset.

The vision is of scientific fascism, presented as utopia. Ivan Illich, in a book from the same period, refers to the end point of industrial society as “BF Skinner’s worldwide concentration camp.” Strong words, but given the popularity of the book, I understand the urgency. The threat of behavioralism is still with us.

And that’s just the ideas. The prose in Walden Two is laughable. Anyone who has ever called Ayn Rand a hack needs to read literally any chapter of this book and apologize. In the novel, the psychologist-king of the titular commune (an obvious Skinner stand-in) sounds like a dumb pigeon’s idea of a smart person.

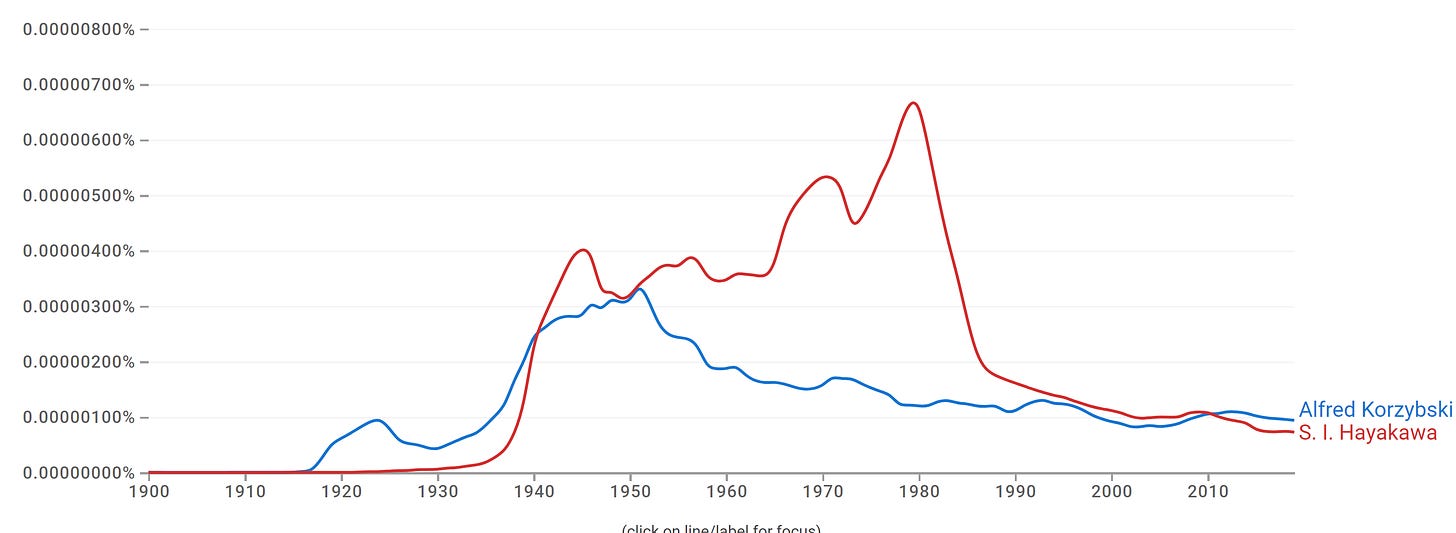

My point, other than just needing to vent, is that some of the “forgotten ideas” are really better off in the dustbin of history. No amount of data can distinguish Walden Two from, say, the General Semantics of Korzybski and Hayakawa. Many of my favorite thinkers from this period mention this movement, but I can’t make heads or tails of it.

The stark red cliff serves as an inspiration for what I’m calling the Hayakawa Question:

Which thinkers have experienced the most dramatic rise and fall in intellectual influence?

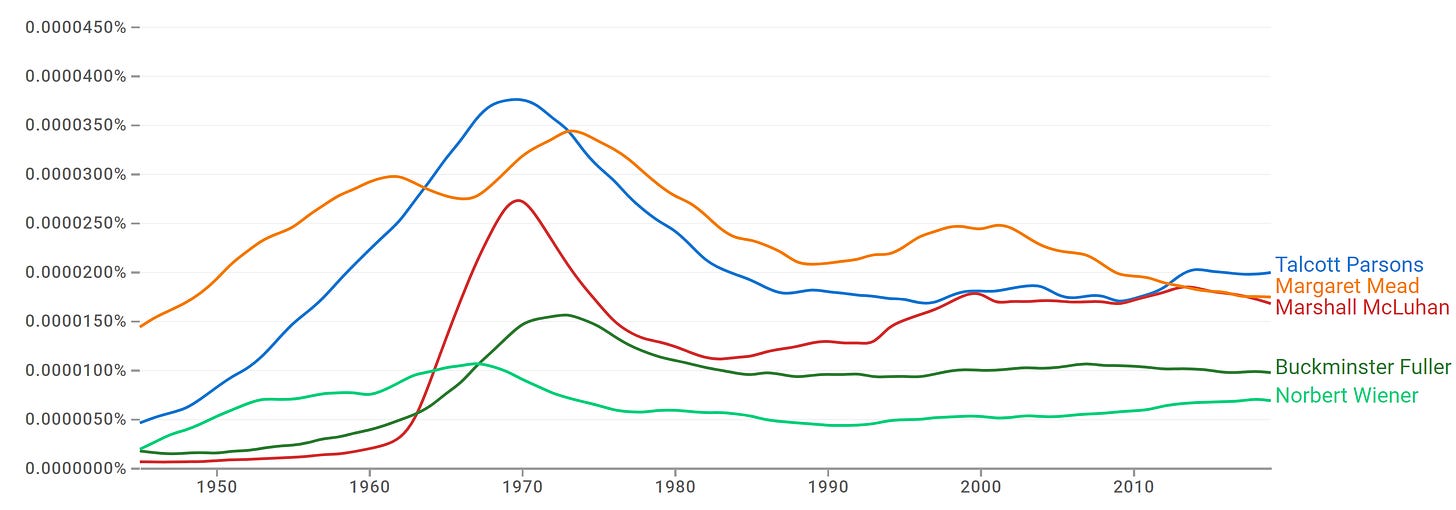

Most immediately relevant for my intellectual project is identifying the thinkers who took advantage of the postwar scientific revolution but who have fallen out of contemporary favor. I started with some of my recent favorites, all of whom were in some way associated with or inspired by cybernetics: Marshall McLuhan, Margaret Mead, Norbert Wiener, and ol Bucky Fuller.

McLuhan’s ascendence and decline was steepest, but recent years have seen a re-appreciation for his work. Mead is the only one still in decline, despite being the most cited for most of the time series…the whole time, really, other than the reign of some dude called Talcott Parsons (???), who a sociologist friend suggested as a plausible candidate for a rapid decline in influence.

The fact that I’d never heard of Parsons is weak evidence of his obscurity; that’s the value of this approach. It turns out that, yes, Parsons is well-known in Sociology…he co-founded the Harvard Sociology department in 1930.

The Parsons example provides further evidence for my theory: he, too, was heavily influenced by cybernetics, was in some ways at the center of it. Another thinker for me to chase down…if you have further suggestions, they’d be very welcome!.

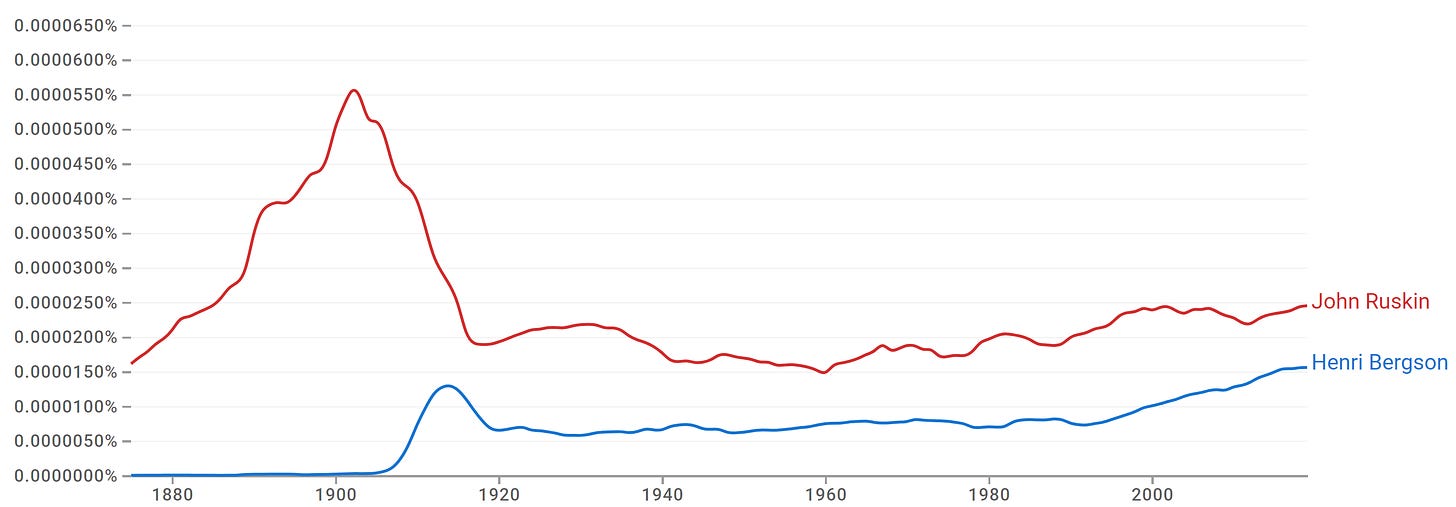

A bit further back in history, I’ve found what I think is the most dramatic decline of any thinker, my current answer to the Hayakawa Question: British polymath and Christian socialist John Ruskin. Another pattern of interest, with a roller-coaster start whose peak has only recently been surpassed, is Henri Bergson, who I think is the key link between the American pragmatists, postwar cybernetics, and the post-structuralist/Marxist tradition.

Google Ngrams cannot serve as the only evidence for the Hayakawa Question. The methodological issues remain: even proper nouns, the most tightly fixed relationship between language and the world, still drift. Though Hayakawa began his career as a semanticist and student of the enigmatic (to me) Korzybski, things took a dramatic turn when he randomly became the Republican Senator from California in 1976.

Wikipedia recounts how he won the Republican primary over “three better-known career politicians,” but was expected to get trounced in the general so badly that his incumbent opponent didn’t even campaign…but then Watergate happened and his status as a political outsider played well enough for him to win. He was apparently so bad at politics that—despite being a sitting Senator—he was unable to get his shit together and didn’t even have the money to run in the primary. “Hayakawa was news media reporters’ favorite fodder, as he was often found napping through important legislative voting.”

Again, I have no context for any of that. But it does explain why, in 1982, his Google Ngrams score falls off a cliff. It doesn’t have anything to do with the interest in his theory of semantics.

I did learn one thing about his mentor Korzybski, though: he coined the phrase “the map is not the territory.”

{ 21 comments }

F 01.17.24 at 6:37 pm

Your charts are leaking.

P.D. Magnus 01.17.24 at 8:05 pm

I used this approach as one strand of evidence in a paper years ago on the concept of natural kinds. Since it is a bit of fixed-phrase jargon rather than a proper name, I tried a few ways to shake out non-jargon uses.

If you’re interested: No Grist for Mill on Natural Kinds

DCA 01.17.24 at 9:05 pm

Great stuff.

There seems to be some inflation of The Dispossessed, since it was published in 1974. It gets a lot of labels, mine is “libertarian utopia which suggests that maximal personal liberty requires abandoning the idea of private property.” I realize that this would make most libertarians’ heads explode.

My own experience of Ngrams is that the default smoothing is too much (though perhaps needed when you are plotting many things).

P.D. Magnus 01.17.24 at 10:45 pm

Oops! That link was broken.

Try… https://jhaponline.org/jhap/issue/view/15

Matthew F Stevens 01.17.24 at 11:01 pm

Probably the best way to summarize Parsons is to read C. Wright Mills’ “translations” in The Sociological Imagination. Unreadable prose, fairly banal conclusions, far as I could tell.

Nathan TeBlunthuis 01.17.24 at 11:27 pm

That poor book. You destroyed it both physically and spiritually.

I’m surprised you hadn’t heard of Talcott Parsons. His rise and fall is a a legendary transition in the history of sociological thought. My understanding is that “Theories of the middle range” was essentially a direct response and critique of Parsons style of theorizing.

M Caswell 01.18.24 at 12:15 am

try “Toffler”.

JPL 01.18.24 at 12:24 am

“The Parsons example provides further evidence for my theory: he, too, was heavily influenced by cybernetics, was in some ways at the center of it. Another thinker for me to chase down…if you have further suggestions, they’d be very welcome!.”

Don’t forget Gregory Bateson. Also, although not so much in the general public, people like Ludwig von Bertalanffy.

Was it Hayek who said, “There are no new bad ideas”? From time immemorial it’s the same old ideas we’re always battling; new people and personalities, but the primitive ways of thinking are still around. E.g., Cassirer’s notion of “mythical thought” does not apply only to “primitive societies”. The General Semantics notion of “identification” seems to have been taken from the esoteric tradition. A field that has never in the least gone in for “General Semantics” is linguistics, and, specifically, linguistic semantics.

John Q 01.18.24 at 3:34 am

M Caswell @7 That was a name that occurred to me also

YL 01.18.24 at 5:12 am

fascinating post, but I would take issue with this line: “[Hayakawa] was apparently so bad at politics that—despite being a sitting Senator—he was unable to get his shit together and didn’t even have the money to run in the primary.” — In fact, he being unable to run reelection campaign was due to two major sociopolitical factors beyond his control: first, by the early 1980s the Republican Party had been undergoing the “Reagan revolution”, becoming more religiously and socially conservative. He himself was not really a conservative figure (when he first ran and won, he happened to be disputing with student protesters in his capacity as university president, and the Republican voters mistook him as an “anti-counterculture” conservative intellectual) and he was even more out of line with GOP’s primary voters six years later. Second, he was, at the time, one of the very few racial minority Republican Senators (and the only Japanese-descent Republican Senator; the other two Japanese American senators were both Democrats, and both from Hawaii); given the racial atmosphere at the time, and given California’s long and uneasily history with Japanese immigrants (one of Hayakawa’s signature achievements was raising awareness about this history of discrimination), he really couldn’t find any ally within his party, and had to collaborate with Democratic colleague basically all the time. So when it came to reelection time, he couldn’t secure in-party endorsements, donors or primary voters.

DavidtheK 01.18.24 at 12:56 pm

B. Fuller will have somewhat inflated results because of the useful properties of the Carbon-60 molecule (which has seen a lot of research since the early 1990’s) which is named for him.

Bob Michaelson 01.18.24 at 5:05 pm

Regarding Sci-Fi: Foundation absolutely crushes Stranger in a Strange Land, and Atlas Shrugged. The latter is really too stupid to be called Science Fiction; it isn’t even a novel, just an extended, tedious polemic.

Bob Michaelson 01.18.24 at 5:12 pm

My errror – while Asimov’s Foundation crushes Atlas Shrugged, as is well should on all grounds, literary and philosophical, Stranger crushes them both.

Scott Anderson 01.18.24 at 6:30 pm

More trouble for counting Hayeks: there’s a “von” in his full name that is sometimes though not always used, but I’m pretty sure I first learned of him as Friedrich von Hayek.

LFC 01.19.24 at 5:15 pm

Re Talcott Parsons: he was the person most responsible for introducing Max Weber’s work to the Anglophone academy; his key book is The Structure of Social Action. In addition to grand theory and exegesis, he also wrote on some specific topics. Probably easier to go to a more accessible tackling of some Parsonsian themes, e.g. by Dennis Wrong in The Problem of Order (1994).

More directly on the question of declines in intellectual influence: some obvious candidates would be proponents of 1950s/60s modernization theory, which gradually lost favor, at least in that form. (Parsons is also relevant here.) However, a lot of social scientists who did modernization theory also did other things, so their N-gram curves may not drop that much. The names would include, among others, Daniel Lerner, W.W. Rostow, Lucian Pye, and Marion Levy, Jr. For background, see e.g. Michael Latham, The Right Kind of Revolution and Nils Gilman, Mandarins of the Future.

Jim Harrison 01.19.24 at 8:26 pm

The guy who disappeared so hard we forgot about forgetting him was Arthur Toynbee.

William Berry 01.20.24 at 8:39 pm

@Jim Harrison:

Ha, good one!

I’ve read Toynbee in the D. C. Summerwell (sp?) condensation of “A Study of History” (ten normal volumes excerpted into three large volumes), which makes me pretty weird, I guess. In my defense, that was likely fifty years ago, when he was not yet so unwellknown.

Alas, Haeckel and Spengler are still hanging in there. Why can’t we forget about those two?

Oh, wait, the Neo-fascists love them, that’s why!*

^Well, H did some important biology, and was a great draftsman, so there’s that.

John Q 01.21.24 at 12:47 am

Decline to obscurity is the norm, I think. Some random examples

Matt B 01.22.24 at 10:27 pm

Erich Fromm might be a good candidate for someone who had a sudden rise in popularity and was then quickly forgotten about.

David Moles 01.26.24 at 3:04 pm

You may already know this, but since you didn’t mention it, I just wanted to highlight that the Library of Congress has a whole catalog of authority records specifically for handling the “Friedrich Hayek” / “F.A. von Hayek” problem: https://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/n80126331.html

It’s not magic, but it does go a long way toward facilitating automated solutions in this kind of situation.

hix 01.26.24 at 5:41 pm

Niklas Luhmann would be my next association with Parsons. Guess this is me getting old – having been exposed to quite a bit of some researcher younger people with an academic career never heard of.

Comments on this entry are closed.