It’s the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington and the Kennedy assassination, both in their way notable events in the history of African American civil rights. But it is also the hundredth anniversary of a different, equally notable event: the racial segregation of the US government in 1913 under newly elected president Woodrow Wilson. [click to continue…]

Posts by author:

eric

The last time the Washington Post was suffering financial difficulties and looking for a buyer, the President of the United States took an interest in getting it a politically sympathetic owner. This was back in early 1933, during the last long lame-duck presidency, when Herbert Hoover was in the White House refusing his appointees’ entreaties to do something about the financial collapse. He claimed he wouldn’t do anything about the nation’s banks unless he had Franklin Roosevelt’s cooperation – and he wouldn’t have Franklin Roosevelt’s cooperation unless Roosevelt swore he would maintain the gold standard and forswear deficit spending.

But Hoover was willing to expend his presidential influence in trying to find the Post a buyer who wasn’t the Democrat and then-Roosevelt-backer William Randolph Hearst.

After talking about the Post with Hoover, newspaper owner Frank Gannett sent an auditor to look the paper over. He found that while the Post had made $23,907 in 1929, it had lost $117,335 in 1930; $140,364 in 1931; and an estimated lost of $275,000 in 1932. Ad revenues had dropped from $1.37 million in 1929 to $629,000 for the eleven months of 1932 with available information.

In consequence, Gannett wrote to Hoover, “the property does not present a very attractive picture.” He went on, “I hate to see the paper go to Hearst. Yet, he seems to be the only one who could afford it at this time, to make any payment for it.” Gannett concluded, “However, if support for the project could be developed, I would be glad to do my part in trying to get control of it and make it a forceful spokesman for the party.”

Notwithstanding his thrashing in the November elections, Hoover, even out of office, wanted the Post to go to “a strong man,” as he wrote on March 28. After leaving DC, Hoover tried to get his former Secretary of the Treasury, Ogden Mills, to join Senator George Moses and Post editor Ira Bennett in a group to buy the Post when it went up for auction on June 1.

Eugene Meyer was still running the Federal Reserve System, though not for long – Roosevelt had declared privately on March 25 that Meyer was on his way out. Meyer was a friend of Hoover’s – though like most of the country he was not, in March of 1933, much enamored of Hoover’s presidency. Nevertheless, he and his wife Agnes remained in touch with the former president.

Meyer bought the Post at auction on June 1, and made himself president, and his wife Agnes vice president. Hoover sent his congratulations. Agnes wrote back that she looked forward to “the opportunity to build up a really strong and independent paper in Washington under present circumstances seemed too important to be renounced.”

Eugene Meyer hired Ralph Robey away from the New York Evening Post “particularly to fight the inflationary policies of Mr. Roosevelt and his crowd, who” – Meyer said with evident annoyance – “thought they could cure the depression by raising the price of gold which was devaluating the dollar and repudiating the explicit contract of government to pay in dollars of the same weight of gold and fineness.” Meyer also objected strongly to the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, and other New Deal measures.

Post reporters complained afterward that Meyer “went over their articles and changed them so that their writers were all disgusted.”

Will we find someday that Barack Obama cared who the Post went to? Will Jeff Bezos take a role in determining the paper’s content? Stay tuned…

The American Historical Association encourages a 6-year “embargo” of completed history PhD dissertations in digital form, because making dissertations thus “free and immediately accessible.… poses a tangible threat to the interests and careers of junior scholars in particular” because “historians will find it increasingly difficult to persuade publishers to make the considerable capital investments necessary to the production of scholarly monographs.”

The AHA is in that last key sentence making a prediction, based on what evidence I don’t know. Have publishers made threats to publish fewer monographs because the underlying dissertations were available online? (As opposed to, because they lose money on publishing monographs, irrespective of where and how the underlying dissertation was available?)

Dan Drezner, a political scientist, and Brad DeLong, an economist, have expressed incredulity.

Economists certainly make working papers freely available online, and have a culture of sharing information. I know of no evidence that economic journals – including journals of economic history – are loath to publish articles based on working papers, nor of evidence that the American Economic Association is seeking to embargo unpublished work in economics.

There is something obviously wrong in a scholarly discipline seeking to limit the availability of knowledge. I don’t think it’s historically how historians have operated, either.

Hanging as inspiration or admonition over the researchers’ sign-in book at the FDR presidential library is a framed application for a reader’s card from Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. There’s a story that historians tell about Schlesinger at the FDR library – that he was there at the same time as some other early FDR biographers, and that he would, if he found something of note, type it up and give it to them.1

I’ve tried to emulate Schlesinger’s openness and generosity myself. There are four writers currently working on books related to my own, and I send them material when I think it apposite – in the hope they will share with me, and also that this sharing will make our respective books stronger, for having been the product of a community of inquiry rather than an individual quest.

When we find ourselves trying to make scholarship less readily available – however good our intentions – we should probably ask ourselves if we can solve our problems some other way.

1I’m nearly sure this story appears in print somewhere, but I don’t know where.

John Maynard Keynes met Franklin Roosevelt on Monday, May 28, 1934. Both afterward said polite things to Felix Frankfurter, who had urged the two to confer: Keynes described the conversation was “fascinating and illuminating,” while Roosevelt wrote that “I had a grand talk and liked him immensely.”

But the best-known account is probably that of Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, who wrote in her memoir, The Roosevelt I Knew,

Keynes visited Roosevelt in 1934 rather briefly, and talked lofty economic theory.

Roosevelt told me afterward, “I saw your friend Keynes. He left a whole rigmarole of figures. He must be a mathematician rather than a political economist.”

It was true that Keynes had delivered himself of a mathematical approach to the problems of national income, public and private expenditure, purchasing power, and the fine points of his formula. Coming to my office after his interview with Roosevelt, Keynes repeated his admiration for the actions Roosevelt had taken, but said cautiously that he had “supposed the President was more literate, economically speaking.” He pointed out once more that a dollar spent on relief by the government was a dollar given to the grocer, by the grocer to the wholesaler, and by the wholesaler to the farmer, in payment of supplies. With one dollar paid out for relief or public works or anything else, you have created four dollars’ worth of national income.

I wish he had been as concrete when he talked to Roosevelt, instead of treating him as though he belonged to the higher echelons of economic knowledge.

In Perkins’s story, Roosevelt did not grasp economic theory, and would have done better with a less figure-laden account of Keynes’s prescriptions. Historians often recycle her description as evidence of Roosevelt’s “limited understanding of some of the matters he had to deal with as president,” as Adam Cohen writes.

And yet we have evidence that Roosevelt was quite happy dealing with economic theory and a rigmarole of figures.

Apropos nothing at all I thought I might address the suggestion, sometimes raised, that John Maynard Keynes’s “love” for Carl Melchior, German representative at Versailles, might substantively have influenced Keynes’s position on what reparations the Germans ought to pay.

Keynes made early calculations for what Germany should pay in reparations in October, 1918. In “Notes on an Indemnity,” he presented two sets of figures – one “without crushing Germany” and one “with crushing Germany”. He objected to crushing Germany because seeking to extract too much from the enemy would “defeat its object by leading to a condition in which the allies would have to give [Germany] a loan to save her from starvation and general anarchy.” As he put in a revised version of the same memorandum, “If Germany is to be ‘milked’, she must not first of all be ruined.”

Keynes also worried that too large a reparations bill might distort international trade. “An indemnity so high that it can only be paid by means of a great expansion of Germany’s export trade must necessarily interfere with the export trade of other countries.”

The point of mentioning it is that Keynes developed these concerns prior to going to the negotiations and meeting Carl Melchior.

Which is not to say that Melchior did not make a great impression on Keynes; as Keynes wrote in 1920,

A sad lot they were in those early days, with drawn, dejected faces and tired staring eyes, like men who had been hammered on the Stock Exchange. But from amongst them there stepped forward into the middle place a very small man, exquisitely clean, very well and neatly dressed, with a high stiff collar which seemed cleaner and whiter than an ordinary collar, his round head covered with grizzled hair shaved so close as to be like in substance to the pile of a close-made carpet, the line where his hair ended bounding his face and forehead in a very sharply defined and rather noble curve, his eyes gleaming straight at us, with extraordinary sorrow in them, yet like an honest animal at bay.

Keynes was so impressed by Melchior’s account of German suffering – both his implicit and explicit account – that he would illicitly confer with Melchior to try to strike a deal whereby the Germans would receive food relief in exchange for giving up merchant ships.

In The Economic Consequences of the Peace, Keynes criticized the treaty not only for what was in it – the reparations demands – but what was not – “The Treaty includes no provisions for the economic rehabilitation of Europe, – nothing to make the defeated Central Empires into good neighbors, nothing to stabilize the new States of Europe, nothing to reclaim Russia; nor does it promote in any way a compact of solidarity among the Allies themselves; no arrangement was reached at Paris for restoring the disordered finances of France and Italy, or to adjust the systems of the Old World and the New.” He warned that without such provisions, ” “depression of the standard of life of the European populations” would lead to a political crisis, such that some desperate people might “submerge civilization itself in their attempts to satisfy desperately the overwhelming needs of the individual.”

At the conference, Keynes himself had made such a proposal, suggesting refinancing the international debts to provide funds for reconstruction and development. Here it is worth noting that Keynes developed the plan after hearing Jan Smuts’s account of “the pitiful plight of Central Europe.”

So it seems that Melchior did matter to Keynes, and inspired him to propose relief for Germany. But as for his critique of the peace, what really mattered to Keynes was British self-interest, which inspired him to warn against reparations before he even went to France, and sympathy for the people of Central Europe, which inspired his “grand scheme for the rehabilitation of Europe” – which of course was only one of many “grand schemes” that showed Keynes’s interest in the long-run welfare of humanity.

The Council on Foreign Relations has a response to my critique of Benn Steil’s Bretton Woods book, in a post by Steil and Dinah Walker. The tenor of the response is conspicuous; Ed Conway notes I “seem to have touched a raw nerve.” Steil himself writes that my criticism is “like being savaged by a dead sheep.”

I’ll set that issue aside for now and just address the substantial areas of dispute here; that is, the gold standard and Pearl Harbor.

The Gold Standard

Of the gold standard, Steil and Walker write,

Rauchway takes specific issue with Benn’s claim that under the classical gold standard “when gold flowed in [the authorities] loosened credit, and when it flowed out they tightened credit,” arguing that this is “at odds with historical evidence.”

Oh?

And then they insert a graphic showing “that long interest rates did indeed tend to rise when gold was flowing out of the United States and fall when gold was flowing in”, adding, “Economics lesson finished.”

I would extend the economics lesson, or anyway the economic history lesson, further. The US was not the only gold standard country. [click to continue…]

When a book reviewer or manuscript referee describes an argument as “persuasive” or “convincing” without explaining exactly what it is that has persuaded or convinced, or alternatively what it would take to persuade or convince, I feel I’ve failed to get my money’s worth. I suspect I’m getting a purely subjective assessment dressed up in fancy language, and I’ve long had a hunch it’s been increasing in use, at least in my discipline.1

But inasmuch as I had only a hunch that irritatingly subjective language was increasingly used, I knew I was being terribly inconsistent, which troubled me. So at last I went to the data.

I searched JSTOR for instances of “persuasive” and “convincing” and their opposites by year in reviews published in the American Historical Review between 1958 and 2007. To weight the occurrences, I also searched AHR reviews by year for instances of the word “that,” reckoning this was a pretty neutral word to look for. I divided the former by the latter to get a sense of the frequency of subjective language in AHR book reviews. Below is the result, which I hope is more persuasive than my hunch.

The language of “persuasive” is on the increase. Unless I’ve made an Excel error.

1I also have a terrible prescriptivist annoyance over “persuaded … that” and “convinced … of” but we won’t get into it.

Today Jim Rickards (author of Currency Wars) says,

Last week I had x ounces of #Gold. Today I have x ounces. So value is unchanged. Constant at x ounces. Dollar is volatile though. #ThinkOz

I know it’s a failing in me, but it is hard not to ponder whether this is charlatanism or delusion. As John Maynard Keynes says in the first sentence of his Tract on Monetary Reform, “Money is only important for what it will procure.” With the stubborn volatility of the dollar, Rickards’s ounces procure rather less than they recently did.

The exhortation #ThinkOz is of course wonderful. I think now of hashtags past…

Last week I had x bulbs of #Tulips. Today I have x bulbs. So value is unchanged. Constant at x bulbs. Florin is volatile though. #ThinkBulbs

Money is a medium of exchange and a store of value, they say.

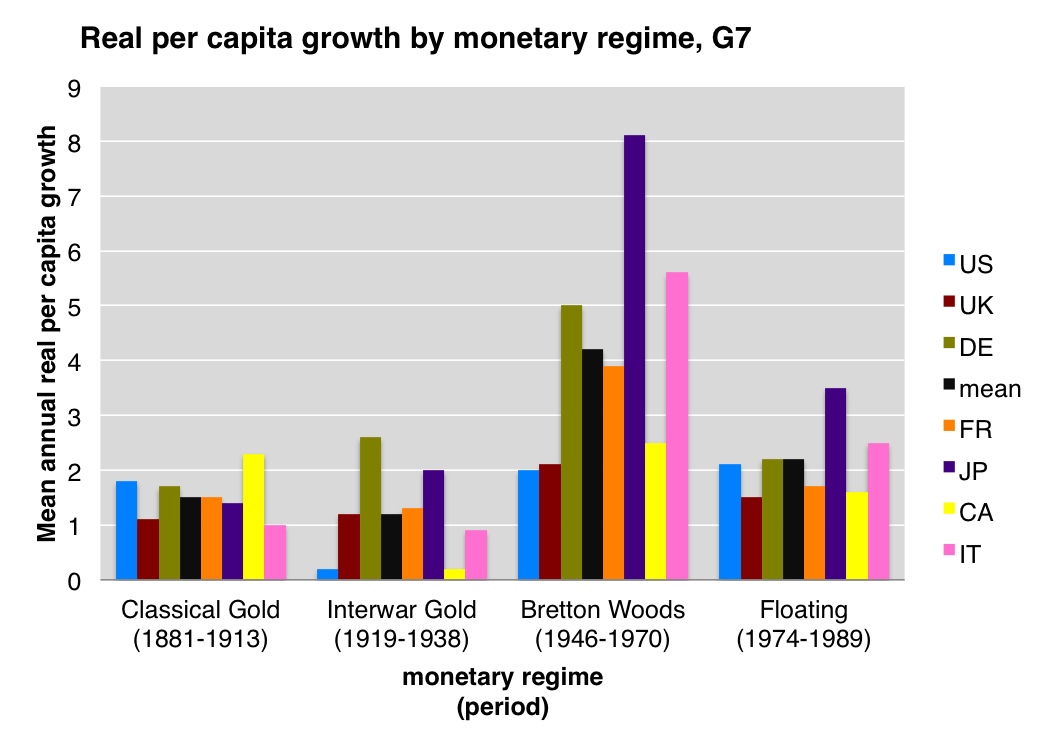

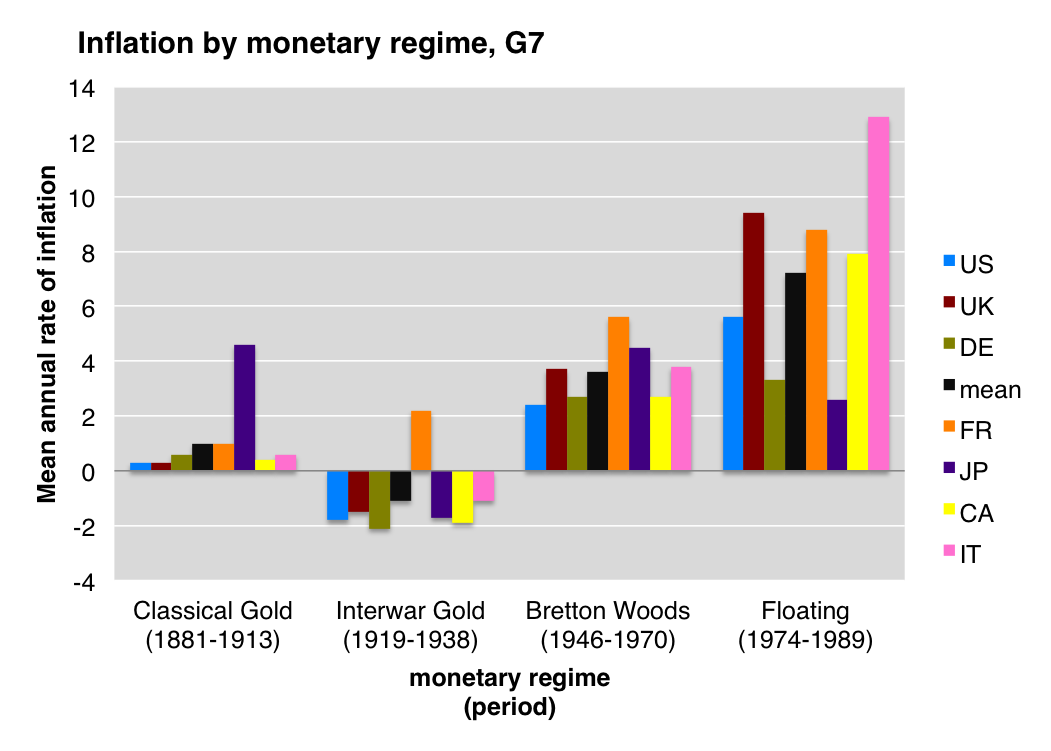

Was the gold standard a golden age, or a gilded one? How does it compare to later monetary regimes? I mean, we know the gold standard was terrible for the US, but what about other countries? I know you want to know, without having to dig in data appendices, so I made you some charts. Because I love you that much. (But not enough to extend the floating exchange rate regime data down to the present; that’s actual work.)

Data from table 1, Michael Bordo, “The Gold Standard, Bretton Woods and other Monetary Regimes: An Historical Appraisal,” NBER working paper no. 4310.

In the recent TLS I have an essay on Benn Steil’s new book on Bretton Woods. Unlike some notices, mine is critical. You can read mine here. If you’re interested in the theory, put forward in Steil’s book, that Harry Dexter White caused US intervention in World War II, read below the fold. If you’re more interested in the late Baroness Thatcher, please carry on down to the other posts for today.

So, I got these two packages from Sweden today. Obviously, this is part two of this episode. Which Jon Ronson wrote about here.

I’m not going to try to analyze the books I received yet, except to note that yes, that’s clearly the Giant Rat of Sumatra speaking the slogan from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, “BORN” as a reference to the original Being or Nothingness and, uh, probably some other stuff. One of the books says “Facsimile” and the other doesn’t. I already confirmed with Jon Ronson that he got one too.

I won’t attempt any further analysis for now. But if anyone else got one (or two) please write in to say…

I would have said “gradually,” rather than “secretly,” but over on Bloomberg I have a little piece on how FDR ended the US gold standard.

There’s widespread disagreement over when the US went off gold – was it with the end of domestic convertibility, which happened on March 6, though it wasn’t made clearly permanent until later? was it with the end of exports, on April 19? Scott Sumner just claimed the US didn’t permanently leave the gold standard at all in 1933, “just temporarily suspended it,” which is an answer Friedman and Schwartz sort of give, though they fudge it – “the gold standard to which the US returned was very different, both domestically and international, from the one it had left”. I myself like the answer given in one article, that the US went off gold “about crocus-daffodil time, 1933.”

Actually, I think the word “disagreement” isn’t quite right – it’s more lack of agreement; I’ve never seen anyone bother to pick apart who prefers which date and why. Obviously it depends on what you mean by “the gold standard,” and what it means to be on or off.

As the Bloomberg post indicates, I’ve been looking into Roosevelt’s intentions and expressed policies, and I’ve become persuaded that he knew pretty clearly what he was doing.

Two weeks before Roosevelt’s inauguration, Keynes wrote,

can it be possible today to forecast a respectable future for [gold], when in the meantime it has betrayed all the hopes of its friends? Yet it does not follow that the monetary system of the future will find no place for gold. A barbarous relic, to which a vast body of tradition and prestige attaches, may have a symbolic or conventional value if it can be fitted into the framework of a managed system of the new pattern. Such transformations are a regular feature of those constitutional changes which are effected without a revolution.

I predict, therefore, that central banks will continue in the future, as in the past, to keep gold reserves for the protection of their exchanges and as an emergency means of settling an adverse international balance.

That’s, in outline, the policy Roosevelt pursued – probably without having read Keynes, but who knows? – beginning with his inauguration. He wanted a managed currency, so he could influence commodity prices, but he also wanted enough gold in US vaults so he could fend off speculative attacks on his managed currency. That’s why he ended convertibility, but didn’t quite announce it. If he said convertibility was done for good and all, it would have been much harder to get hoarders to return their gold to the vaults.

It’s also, of course, the basis for the dollar that became the anchor of the Bretton Woods system, in which, Keynes would later say, reprising his language of 1933, gold had become a “‘constitutional monarch’, so to speak, which would be subject to the constitution of the people and not able to exercise a tyrannical power over the nations of the world.”

FDR’s intentions matter because if he meant to do what he did, if he was carefully managing expectations, then the history of his monetary policy becomes a useful text applicable to modern affairs.

Meanwhile, in modern affairs, it’s not a good season to be a gold enthusiast. As usual, the answer to a headline that ends in a question mark is “no.”

In the current New Yorker, Louis Menand says there is a puzzle about how Franklin Roosevelt got reëlected:

When Roosevelt ran for reëlection in 1936, the unemployment rate was 16.9 per cent, almost twice what it had been in 1930. Yet he won five hundred and twenty-three electoral votes, and his opponent Alf Landon, eight. When Roosevelt ran for the unprecedented third term, unemployment was 14.6 per cent. He carried thirty-eight states; Wendell Willkie carried ten.

When Menand says unemployment was 16.9 and 14.6 percent when FDR ran for reëlection, he is counting federal relief workers as unemployed. According to the economist who constructed the series Menand is using, people working for the WPA were morally the same as concentration camp workers in Germany in the 1930s. If Menand realized that, the puzzle would go away: FDR and his New Deal were popular because they gave people jobs and sparked a rapid recovery.

For more, please see here.

In the sub-basement of the old State, War, and Navy building in Washington, DC, there’s a door with a small, yellowing card next to it reading, in Selectriced letters, “AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION.” (There is, of course, an ongoing debate between the authenticity faction and the archival preservation faction over whether the card ought to be replaced with one made of acid-free paper.) Inside the room is – well, is a lot more dust than there should be, actually, but also an agglomeration of black boxes wired to a console distinguished by its steel heft and Bakelite knobs. There’s a row of lights across the top of it, each with a paper label underneath – 1941, 1942, 1943, 1944, and so on – years extending back to the dawn of the republic and forward, with the limited foresight of the original engineers, to 1976. Fortunately, that year – with a special bicentennial appropriation – the AHA was able to add an auxiliary console, carrying the lights forward to the millennium. But no further; nobody works here full time anymore. [click to continue…]

Maybe Hyde Park on Hudson only really makes sense from a British point of view. It’s right there in the title – “Hyde Park on Hudson” reminds you that there’s another Hyde Park, “on Serpentine,” if you like, in London – and if you didn’t catch it from the title, Queen Elizabeth says it in the middle of the movie. “Why is it called Hyde Park? Hyde Park is in London. It’s confusing.”

The movie itself would be confusing if you don’t recall that Hyde Park in London, although technically crown property, is now overrun by the public and indeed home to radical speech and protest, and if you don’t concede that this description also applies pretty well to Hyde Park in New York, formerly a crown colony, and home to Franklin Roosevelt, then – in 1939 – seen as a radical tribune of the American people.

The two kindred parks yield two kindred stories.

In one, FDR’s distant cousin Daisy has an affair with him, believes she is unique, then discovers he has other lovers. One of them, FDR’s secretary Missy LeHand, tells Daisy that she will learn to share. And she does; in the end, happily.

In the other story, George VI (“Bertie”) and his queen, Elizabeth, come to the American Hyde Park to visit the President and court his support for Britain’s defense. It is the first visit by a British monarch to the United States, and a dark hour for Britain. But Bertie hits it off with FDR, feeling he has found a father figure in him, and declaring (in one of several bits of invention) that the two nations have forged a “special relationship.”

In case we miss the point, Daisy also says she has a “special relationship” with Franklin Roosevelt. Bertie’s special relationship with FDR is no more unique than Daisy’s. The movie ends on a high note, but we know that one day, soon, the British will learn they must share his promiscuous affections; by Bretton Woods and Yalta, FDR was courting Josef Stalin.

Perhaps, like Daisy’s bond with FDR, Britain’s tie to the US is not less special because America is so profligate with its affections.

Historians are supposed to quarrel with the film’s depiction of Roosevelt. I don’t think it’s necessary; the Roosevelt in the movie isn’t the human, historical FDR – he’s America personified – smiling, inscrutable, shameless, exploitive, powerful, popular. Bill Murray doesn’t do an impersonation – though he gets the smile right.

But there are essential things about Roosevelt the film does show, more economically and elegantly than I imagined a work of fiction could.

He got along because he made people feel good about themselves – after their meeting, Bertie bounds up the stairs, two or three at a time.

And he let people think he had not made up his mind, when in fact he had – he talks ambivalently about an alliance with Britain, but by the end of the movie we realize he has meant to make it happen, and has worked hard to make it happen.

And people did look to him, craving his attention, trusting him, even though his interior life was finally inaccessible.

The meeting between FDR and Bertie is a really terrific scene, as are all the scenes between Bertie and Elizabeth – but especially the one when they discuss the web of FDR’s promiscuity, and conclude with relief they did not bring Lilibet. There are some gorgeous scenes of the parklike Hudson scenery, humid, rolling in thistle capped by pale blue skies stacked with billowing clouds. It is a beautiful film to look at, and to think with.