ETA 24h later: I told my girls that I was wrong and that everyone on the whole internet explained that they could perfectly well go on and win the Fields Medal if they were inclined to be mathematicians, and that being super-fast at mental arithmetic as a child isn’t the same as going on to make interesting discoveries in math as an adult, and that I was a jerk, and also wrong. Additionally, wrong. So if Zoë (12) wants to take time out from her current project of teaching herself Japanese, or Violet (9) wishes to take a break from her 150-page novel about the adventures of apprentice witch Skyla Cartwheel, then, in the hypothetical words of the Funky Four Plus One: “They could be the joint.” [Listen to this song because it’s the joint.]

“Y’all’s fakes!”

If you’re impatient you can skip ahead to 3:20 or so. Tl;dw: the overly scientific Princess Bubblegum, having snuck into Wizard City dressed in wizard gear along with Finn and Jake, is buying a spell from a head shop place that sells potions and spells and all that schwazaa. But she wants to know what the spell’s made of. “Magic?” Then she asks…read the post title. Then they get busted.

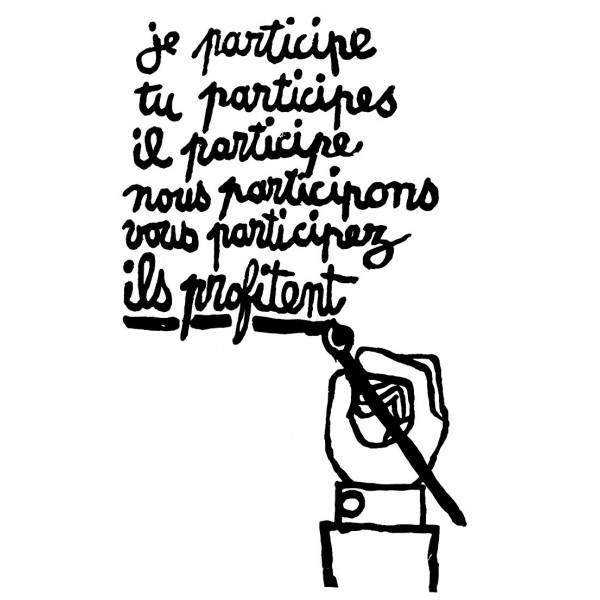

“So, kiddos,” I asked my kids in the elevator on the way down to the pools today, “are numbers real, or are they just something people made up?” Violet: “Real.” Zoë: “Real.” “That’s correct! Numbers are real! Like what if there were a sakura with its five petals, and it were pink, but no humans existed. Would it still be pink? Would it still have five petals?” [At approximately floor 14 I decided to bracket color problems.] “Yep.” “And things that are true about the number five, would they still be true too, like would five times five equal twenty-five and stuff?” “Totally.” “Could two plus two ever equal five, if there were no people around to check?” Zoë: “No, obviously not. Even now, people have lots of different languages, but if they have a word for five, then that word is about something that’s not two plus two, and it’s twenty-five if you multiply it by itself, and stuff like that. And people discovered zero two times.” “Correct! Math is real!” Zoë: “Also people discover important things about astrophysics with math, and then the same numbers keep turning up, and why would it be like that if there wasn’t really math?” “OK, so, we can keep discovering new things about math, right?” Girls: “Sure. Mathematicians can.” Me: “Maybe you! No, not you. I’m sorry.” Zoë: “I know.” Violet: “What?!” Me: “No, you’re both very intelligent children, you can learn calculus just as well as anyone, but if you were going to be an incredible math genius or something we’d kind of already know. Sorry.” [John was doing laps at this point. I’m not sure he approves of my negative pedagogical methods.] Zoë: “What’s set theory?” Me: “It’s just what it sounds like. There are sets of numbers, right, like all the prime numbers, all the way to infinity? Theories about that.” Violet: “I’m going swimming with daddy.” Me: “OK, there’s just more math out there, waiting to be discovered–but sometimes mathematicians come up with stuff that’s crazy. Like string theory. Which maybe isn’t a theory?” Zoë: “Why not?” Me: “I think they might not have any tests at all proposed by which to prove their hypotheses.” Zoë was very indignant: “That’s not a theory at all! What is that? Me: “Math that’s really fun and weird and entertaining if you understand it? John, can string theorists not propose any test whatsoever that would prove their hypotheses or is it rather the case that we lack the capacity to perform the tests that would figure it out?” John: “It’s an important distinction and I think it’s the latter. Like, was there an even or an odd number of hairs on Zoë’s head on March 23, 2006? There’s some true fact of the matter, but it’s indeterminable.” Me: “Well they can’t be demanding time travel, Jesus.” Violet: “We should have counted!” BEST. SUGGESTION. ERVER!1

OK, so, I’m a Platonist about math. Like lots of mathematicians I knew in grad school, actually, but not by any means all. In fact, some were a little embarrassed about their Platonism. My algebraic topologist friend was of the ‘numbers are the product of human intelligence’ school (N.B. while I understood vaguely what my HS friend who was also at Berkeley did set theory was writing is his diss on, in a kind of babified ‘along these lines’ way, I genuinely could not understand at all what my algebraic topology friend was doing. What, even?) This reminds me of an idiotic discussion I had in a Classics seminar with me vs. an entire group of people (including my dissertation adviser). They all maintained that there were no structures absent human recognition/simultaneous creation of the structures. As in, absent the evolution of humans on the earth, there would be no regular geometric structures. I was just like:?! Crystals that are even now locked in the earth inside geodes, where they will never be seen? Beehives? Wait, are these all imperfect and gently irregular, and thus unsatisfactory? They shouldn’t be because many of the crystals are perfectly regular. Anyway OH HAI ITS BENZENE? I…was neither presented with any compelling counter-arguments nor was I winning the argument. It was very irritating. Then I brought up my own objection–this is steel-manning, I guess: benzene was created/isolated by humans? Like Faraday even? Fine, NOBLE GASES! NOBLE GAS MATRIXES! I can draw argon on the board! Look at how this shell is so full of electrons mmmmm this probably doesn’t want to react with anything cuz it’s so lazy amirite guys (but we can make it (but also in the Crab Nebula it’s happening naturally!) but that’s irrelevant))! I still…did not win the argument. We were forcibly moved on to another topic.

I know people wanted to discuss the external reality/human-created nature of numbers and math in the earlier thread, but we got trolled by someone who was ‘just askin’ questions’ and said I ‘had to check with each and every commenter about exactly what he/she intended’ before taking offense ever at something, say, sexist that someone said. (HhHHmmmyoursuggestionfascina–NO.) Now’s your chance!

N.B. Long-time CT commenter Z alone is permitted to use humorous quotes from recalled Barbie and Malibu Stacey dolls in his discussion with me. If anyone else does I will smite you. With smiting.