Oh, Belle. Belle, Belle, Belle. First, you told us some authors were such a bunch of sexist dillweeds that you didn’t really like their novels all that much. In a throwaway sentence! A sentence that made it clear that you in fact didn’t read such books at all, but merely checked the covers for sexist content and then threw the books away in the trash. In. The. Trash. And then John said you could read fast. Biased much LOL! Yeah, well, so fast that you stopped reading books completely after you reached a sexist sentence! Because that’s manifestly what ‘reading fast’ means. Yes, and then you had an actual man testify again on your behalf that you finished books even if you didn’t super-love them. Like–probably the only chick in the world, seriously! How was any of us to know that “reads books fast” means “reads books”? What is this, some kind of crazy advanced logic class, or a blog?

So then you explained at length, that you were only talking about this one group of male authors who wrote more or less from the ’50s on, and that you didn’t like their novels because you thought they weren’t good novels. When since is that a reason not to like a novel, I would like to know, Missy? Any anyway, Belle, your problem is that you’re reading the wrong thing. Nobody cares about these books anymore! Or, as a commenter suggested: “No. It seems your definition of ‘important’ is skewing your choice of reading, so not surprising that your results are skewed. I’d suggest that you drop everything else for a while until you’ve finished reading all of Pratchett and Banks.” [Here I must note that for whatever odd reason this rubbed me the wrong way. I have already read all of Pratchett and Banks (except maybe one Tiffany Aching one?). The knowledge that there will be no new Iain M. Banks novels dismays me. He’s one of my all-time favorite writers full-stop. WHY AFTER 500 COMMENTS WOULD SOMEONE NOT ASK IF I HAD READ THEM ALL FIRST BECAUSE YOU KNOW, I VERY WELL MIGHT HAVE? Unnamed commenter: I don’t hate on you; it was almost bad luck that you…naw, you still shouldn’t have been so patronizing. But, like, talk to me, dude, what were you thinking?]

Well, dear readers, someone does care about these authors. Someone cares very, very much, and that man is University of Toronto Professor David Gilmour. In a recent interview with Random House Canada’s Emily Keeler, he explained his teaching philosophy:

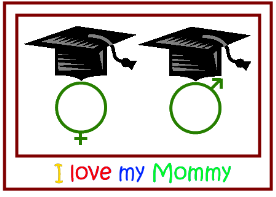

I’m not interested in teaching books by women. Virginia Woolf is the only writer that interests me as a woman writer, so I do teach one of her short stories. But once again, when I was given this job I said I would only teach the people that I truly, truly love. Unfortunately, none of those happen to be Chinese, or women. Except for Virginia Woolf. And when I tried to teach Virginia Woolf, she’s too sophisticated, even for a third-year class. Usually at the beginning of the semester a hand shoots up and someone asks why there aren’t any women writers in the course. I say I don’t love women writers enough to teach them, if you want women writers go down the hall. What I teach is guys. Serious heterosexual guys. F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chekhov, Tolstoy. Real guy-guys. Henry Miller. Philip Roth….

[click to continue…]