Scholars and critics may learnedly dispute when Schulz did his finest work with Peanuts. Let me say, I’m reading Volume 11 (1971-2) with the younger one, and we were dying over the whole Bunny-Wunnies business. I’ll quote from the wiki bibliography of Miss Helen Sweetstory’s collected works:

The Six Bunny Wunnies and Their Pony Cart

The Six Bunny Wunnies Go to Long Beach

The Six Bunny Wunnies Make Cookies

The Six Bunny Wunnies Join an Encounter Group

The Six Bunny Wunnies and Their XK-E

The Six Bunny Wunnies and Their Water Bed

The Six Bunny Wunnies and Their Layover in Anderson, Indiana

The Six Bunny Wunnies and the Female Veterinarian

The Six Bunny Wunnies Freak Out

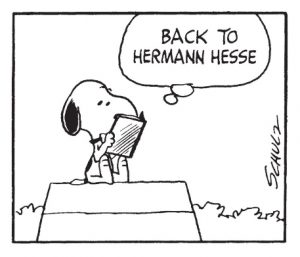

Let’s not forget the time Snoopy became disillusioned with Miss Sweetstory’s collected works and gifted the set to a grateful Linus.

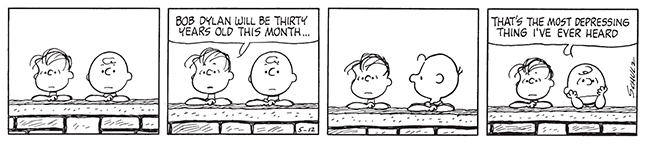

And then June, 1971 rolls around.

Golden, man.

UPDATE: Due to an exegetical difficulty arising in comments, I am posting the following, for scholarly reference.

{ 54 comments }

Anderson 08.20.16 at 4:49 pm

You left out The Six Bunny-Wunnies Visit Plains, Georgia.

I forget sometimes that Peanuts was once good.

LFC 08.20.16 at 5:24 pm

You also left out The Six Bunny-Wunnies, Their Kierkegaardian Leap of Faith, and Its Reception by Certain Neo-Hegelians, with an Excursus by J. Holbo on the relation of the preceding to recent trends in analytic philosophy and libertarianism, etc.

Russell Arben Fox 08.20.16 at 6:52 pm

There was endless wisdom in the work of Schulze, circa 1960s-1980s. What you’re doing with your daughter is wonderful, John; I’d love to do the same.

J-D 08.20.16 at 9:38 pm

According to Wikipedia, the Best Buy format was very popular.

John Holbo 08.20.16 at 10:20 pm

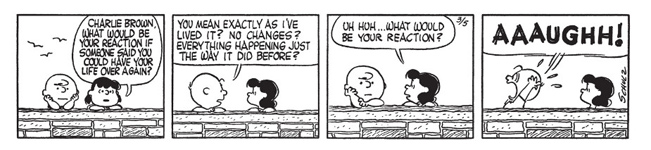

I don’t think “Peanuts” is Kierkegaardian. But it’s certainly Nietzschean. There’s a strip in which Lucy confronts Charlie Brown with the challenge of Eternal Recurrence. What if you had to do it all again, with no changes? Nietzsche says some people will say it sounds glorious, some will despair. Charlie Brown, of course, runs away screaming.

John Holbo 08.20.16 at 10:22 pm

“You left out The Six Bunny-Wunnies Visit Plains, Georgia.”

We actually haven’t gotten to that one yet! I shouldn’t have checked the wiki entry because I slightly spoilered myself. I’m still looking forward to strips in this volume in which “The Six Bunny-Wunnies Freak Out” is banned by the local school board and the kids are upset about it. That’s awesome.

Yan 08.20.16 at 10:50 pm

“But it’s certainly Nietzschean.”

Nah, it’s Schopenhaurean.

LFC 08.20.16 at 11:34 pm

from one of the links:

Was aware of the main Peanuts characters, of course, and occasionally (if I may date myself) read the strip in the newspaper (I mean the hard-copy newspaper), but I don’t believe I’d heard of this Bunny Wunny series. Which may be b/c it somewhat predates my occasional reading of the strip.

LFC 08.20.16 at 11:46 pm

There’s a strip in which Lucy confronts Charlie Brown with the challenge of Eternal Recurrence. What if you had to do it all again, with no changes? Nietzsche says some people will say it sounds glorious, some will despair. Charlie Brown, of course, runs away screaming.

Well, the key phrase here seems to be “with no changes.” Obviously Charlie Brown does not want to re-live his life as himself. Ask the same question of, e.g., a gorgeous movie star, a Nobel Prize winner, a multi-time winner of Wimbledon, a brilliant novelist, or even of some ordinary person who has had a reasonably happy life, and you might get a different answer.

Recurrence as oneself is one thing. Recurrence as someone else is something else. Obvious point, but relevant to the Charlie Brown case.

LFC 08.20.16 at 11:49 pm

p.s. on second thought, probably did run across refs to the Bunny Wunny bks and forgot. That seems more likely.

Dave Maier 08.21.16 at 2:52 am

Russell @3: “There was endless wisdom in the work of Schulze, circa 1960s-1980s.”

You’re thinking of Klaus Schulze, who indeed did his best work then. Charles Schulz spells his name without the “e”.

Of course I remember the Six Bunny-Wunnies, especially the Freak Out episode. Not to spoil it, but I also remember when Snoopy starts writing what eventually turns out to be an unauthorized biography of Miss Sweetstory. Charlie Brown confronts him with this, but the WWI flying ace is out on a mission and cannot be reached for comment.

Also, LFC’s idea is terrific. I would totally read that one.

peter ramus 08.21.16 at 4:40 am

Charlie Brown, of course, runs away screaming.

The bureaucrat can muster no more than a sigh in this recent languagehat post:

robotslave 08.21.16 at 8:54 am

Christ help me, but I when I read the Bunny Wunny strips in reprints (this would have been in the late ’70s) I didn’t take them as anything more than an indictment of the mercenary kid-lit content mill series of the day– Hardy Boys, Bobsey Twins, Nancy Drew, and their ilk.

Of course, I was like 7 years old. But still:

I’m not sure these strips are going to have their full and very necessary impact on contemporary 7-year-olds; what those people need, desperately, is satire of their own pop culture, and not satire of the pop culture of their parents.

Or grandparents.

Bill Benzon 08.21.16 at 9:24 am

Isn’t the kick-the-football bit the prototype of the eternal R?

Graffiti style:

https://flic.kr/p/tWuu6w

Yan 08.21.16 at 3:13 pm

Seriously though, Peanuts is anti Nietzsche, whether or not that’s a good thing. Hence the deep humanity and empathy, more in keeping with Schopenhauer’s ethics than Nietzsche’s condemnation of pity. Charlie kicking the football is a parody of eternal return, affirming eternal life only in the form of passivity and despair: the goodness of grief. But of course Schultz and the reader are meant to be on Charlie’s side, so it’s not Nietzschean critique of Charlie as last man. The closet thing to Nietzsche is Snoopy as Dionysus. But Snoopy is not a protagonist but a temptation, who the reader is always led to recognize as a form of madness, not as an ideal.

But hey kids, if it’s cooler to stick the name Nietzsche in your word salad high low cultural reference collages, enjoy.

John Holbo 08.21.16 at 3:32 pm

“if it’s cooler to stick the name Nietzsche in your word salad high low cultural reference collages, enjoy.”

I defer to your evidently greater experience in that department, Yan.

ZM 08.21.16 at 3:40 pm

Yan also disagreed with you about Kierkegaarde and said he was an atheist on the thread a while back.

Yan 08.21.16 at 3:41 pm

Thanks for keeping track of my crimes, citizen ZM.

ZM 08.21.16 at 3:48 pm

You kept insisting to me Kiergegaarde was an atheist.

Yan 08.21.16 at 4:07 pm

Yes, specifically: either a closet atheist or an unconscious atheist in denial.

Obviously a contentious claim, but not absurd. The man literally says that truth is a state of becoming and that faith is becoming rather than being a Christian. Not a stretch, arguably a logical entailment even.

These contrarian crimes have got nothing on my claim in another thread that Ferante might be very good but not among the greatest. I’m in witness protection for that one.

Yan 08.21.16 at 4:18 pm

John, sorry for the unnecessary snark there, just thought the Schopenhauer contrast was worth considering. I do think the rest of my post makes a substantive point on that topic, worth discussion.

Yankee 08.21.16 at 4:37 pm

Personally, the only kind of “what comes next†I can think about involves a chance to “try againâ€. I don’t know how that would work for the rest of y’all, but I so rarely do. Anyway that’s what I’m holding out for.

Yan: Many people seem to think Spinoza was an atheist also. He wasn’t a Presbyterian, that’s true.

LFC 08.21.16 at 5:53 pm

I’ve read a little Schopenhauer. (Had to read bits of The World as Will and Idea a long time ago in a seminar that was [supposedly] about methods/epistemology in social science and IR specifically.)

Anyway, just about the only thing I distinctly remember (apart from some refs to Buddhism) is a passage in which Schopenhauer rants about noise, like ‘random’ distracting noise, and how much he hates it. That resonated with me.

Yan 08.21.16 at 8:27 pm

Yankee 22, the Spinoza comparison is interesting, but my claim about Kierkegaard’s a tougher case because he presents himself as a Christian, in contrast to Spinoza who gives us an abstract philosophical theism that doesn’t even pretend to resemble that of everyday monotheism.

But to admit he’s no Presbyterian is to vastly underemphize his weirdness. He’s a Christian who says that a pagan worshipping an idol with true faith can be a true Christian, making doctrinal content irrelevant: in his words, it’s only the how not the what that matters. By that extraordinary logic, a worshipper of reason in true faith is a “real” Christian, or a worshipper of humanity, or of the self, and so on. Hell, why not even a devout, subjectively existing in the passion of faith, Satanist?

LFC 22, he’s a really funny, viciously witty write, as in that passage. But that one also has a weird ugly classism to it, since he concludes that noise is a way in which manual laborers violate the rights of intellectuals to uninterrupted thought.

His relevance here is that Nietzsche’s mature philosophy is posed directly against Schopenhauer, but Peanuts has important similarities to Schopenhauer: a pessimistic view of life and human nature in which Charlie brownish grief is inevitable, in which humans are essentially unbearable to each other, and the only good is to lessen each other’s suffering as much as possible.

Nietzsche identifies that kind of ethics as nihilist, sees it as the core of both Christianity and Buddhism, and constructs his entire philosophy around its overcoming. So it’s unlikely Peanuts is Nietzschean on any plausible reading. (Consider too how fitting it seems that the strip has become so embedded with the Christian Christmas story in the cultural psyche–because the New Testament is in many ways it’s philosophical core: suffering and mercy, that’s all there is.)

LFC 08.21.16 at 9:36 pm

Yan @24

Yes, your argument re Schopenhauer vs. Nietzsche (w.r.t Peanuts) is clearly stated (and seems reasonable enough to me). But since I really haven’t read N., I can’t say much more than that.

John Holbo 08.22.16 at 6:45 am

“By that extraordinary logic, a worshipper of reason in true faith is a “real†Christian, or a worshipper of humanity, or of the self, and so on.”

Kierkegaard is clearly not your average Lutheran – I don’t think it has ever crossed anyone’s mind that he might be a Presbyterian – but I fail to see what Kierkegaardian argument could making worshiping reason = ‘real Christianity. Unfold this extraordinarily logic.

ZM 08.22.16 at 9:47 am

John Holbo,

It is due to Yan thinking people are saved and go to Heaven in Lutheranism if they have true faith in anything whatsoever, when you have to have true faith in the Lutheran Christian God actually. That was his argument last time anyhow, maybe he’ll give you a different argument this time. One of my aunts by marriage is Lutheran and they are actually very strict about this, she is married to my uncle who was a Catholic priest and he had to get baptised in the Lutheran Church if he wanted to take communion there. He decided it was ecumenical so the theology was OK and he thinks it’s the same God anyhow.

Also Peanuts is a humourous comic strip which went on for years and was extraordinarily popular. I don’t see how a humourous comic strip has a pessimistic view of human nature, it’s not even sharp cutting black comedy. Plus everyone loves the characters and they are very popular so how does Peanuts comics show people are unbearable to one another?

LFC 08.22.16 at 1:18 pm

@ZM

Yes it’s humorous, but there is a pessimistic (or is it more a stoic? anyway not ‘happy’) undertone. Lucy is continually unbearable to Charlie Brown, continually tells him he’s worthless and incompetent and a loser etc., a self-image he internalizes. Schroeder the pianist is basically a narcissist, Lucy is a nasty jerk, Linus is a regressive infantile mess, Charlie Brown is a latter-day Sisyphus whose life is one defeat after another. The only halfway ‘normal’ character is a dog who thinks he’s flying a Sopwith Camel* in WW1.

[*or whatever the damn airplane is called]

Yan 08.22.16 at 1:45 pm

Holbo 26, never crossed my mind, either. Yankee brought up Presbyterianism, not me. But my comment to Yankee applies to “not your average Lutheran,” too: that profoundly underestimates his weirdness. I think he so twists Christianity beyond recognition that it’s pointless to try to situate him with denominational (just mistyped that as demoninational–coincidence?) coordinates.

Here’s the logic, which I don’t think is that hard to see, even if it involves some controversial drawing out of suppressed premises:

1. faith is about how, a way of existing, a passion rather than an act of will, e.g. faith is like romantic love, and faith is not like rational decision or consent (“subjectivity is truth”–which doesn’t mean, for the record, that “truth is subjectivity”, only that the truth of faith or existential truths are objective truths about subjective states, the issue is the truth criteria of forms of life, not of states of belief or propositions)

–> 2. faith is not about what, not about the object of passion, the reasonableness or truth of the object believed (objectivity is not truth), it is a question of one’s way of relating to the object of faith, not to the nature of that object

–> 3. one can authentically be in a state of faith toward the wrong object and fail to be in a state of faith toward the right one. (Here’s where I think K is either failing to admit the consequences or, as a closet atheist, concealing them: this means, of course, that the entire idea of a “right” or “wrong” object of faith is groundless. If subjectivity is truth, the object is irrelevant in principle, not just in practice.)

–> 4. For Kierkegaard, (true) “Christianity” = “faith” = “becoming subjective”

–> 5. a true Christian can at least in principle achieve faith (a purely subjective way of relating, independent of the object’s nature) in any object, though in practice some would be more difficult than others. I see you only explicitly objected to “reason”–which is probably the most difficult in practice (though you should clarify whether your skepticism is only to that case, or the others too).

The practical problem in the case of reason is that it seems on K’s own terms to be incompatible with faith. Faith is a subjective passion that an occur only when the resistance of reason is withdrawn. But remember the distinction between the how and the what. The object does not determine the relation. If I worship reason on rational grounds, then of course it’s not faith. But notice, first of all, that this sentence really strains the limits of sense. In what sense can one “worship” on rational grounds? On the contrary, if I say someone “worships” reason, I’m implying that their commitment to rationality is false: I’m suggesting, usually pejoratively, that they have a non-rational commitment to the human capacity to use logic to distinguish truth from falsehood, they believe in its general reliability and in the species general capacity to use it well out of desire or hope or fear, not on reasonable grounds.

So, yeah, you can have “faith” in K’s sense in reason: you can love it, find your highest hopes in it, and commit to it despite rational doubt and in the face of even absurd evidence to the contrary, out of a passionate demand that it be so, and you can do so as a form of subjectivity, as an organization of existence, devoting and enacting that passion in every word and deed. And yeah, by the logic K has commited himself to, that’s true faith.

Yan 08.22.16 at 1:46 pm

Shorter version: for K, the “correct” object of faith is faith itself.

Yan 08.22.16 at 1:55 pm

ZM 27,

What LFC says @28. I’d add that Charlie Brown’s bleak worldview is clearly the center of the strip, so to the degree that you find counterexamples (like Snoopy), they must be seen through that central perspective (as I suggested above, Snoopy is, often literally, a figure of insanity, suggesting madness is the only alternative to “good grief”). It’s also worth mentioning that, in good existential forlorn fashion, the adults in this world–the gods who should, presumably, be guaranteeing safety and justice and happiness–are either absent or virtual ghosts, disembodied, ineffective voices.

Anyway, take a look at the strips and imagine how they’d look if you took out the jokes and made them straight, noncomedic descriptions of life. Little boy gets spurned by other children, fails to get a valentine’s card, strikes out at the game, isn’t invited to the party, and is tricked into trying, and failing, to kick the ball again.

I’m reminded of a website that takes all of the cat’s dialogue out of Garfield cartoons, and you realize that it’s not just an accidental effective. The cartoons are objectively depressing. They are, in fact, about human atomism, loneliness, an inability to connect.

http://shutupgarfield.tumblr.com/

Yan 08.22.16 at 1:59 pm

I mean, would a cartoon version of Lord of the Flies made with Peanuts characters really be that much of a stretch?

John Holbo 08.22.16 at 2:04 pm

“And yeah, by the logic K has commited himself to, that’s true faith.”

By the logic you have committed him to. The question then being: is K obliged to be obliging to all this? I think not. The short version why not is that, for Kierkegaard, ‘eternity in time’, a synthesis of finitude and infinitude, is a key element of the equation. Which you have omitted. Faith has to do with making the movement of infinity and getting finitude back. This is why the incarnation is pretty important for him. I don’t doubt that you can convict him of various heresies on this basis, but I don’t really see how, say, worshiping reason could fit the bill. Or bellybutton lint.

John Holbo 08.22.16 at 2:28 pm

“Seriously though, Peanuts is anti Nietzsche, whether or not that’s a good thing.”

Returning to this comment, I suspect your reaction may be due to insufficient familiarity withthe Nietzsche passage in question. From “The Gay Science”, 341:

The Heaviest Weight. – What if some day or night a demon were to steal into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: ‘This life as you now live and have lived it you will have to live once again and innumerable times again; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sigh and everything unspeakably small or great in your life must return to you, all in the same succession and sequence – even this spider and this moonlight between the trees, and even this moment and I myself. The eternal hourglass of existence is turned over again and again, and you with it, speck of dust!”

So we have Lucy’s question, per Charlie Brown’s clarification. (I have updated the post so scholars can consult Schulz’ original.) And Nietzsche foresees Charlie Brown’s reaction:

“Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus?”

Reader, he did.

Of course, Nietzsche goes on to suggest a different reaction would be happier and healthier, but I don’t think Charlie Brown is an especially happy, healthy specimen. (I think you agree, Yan.) But not being healthy doesn’t make him anti-Nietzschean. It just makes him the sort of person Nietzsche is most troubled by: the small man. The broken specimen. I think it is not unreasonable to suspect that Schulz, too, is preoccupied by the fate of the small man, the broken specimen. (I think you agree, Yan.)

Yan 08.22.16 at 3:36 pm

John, I apologized for my earlier rudeness. Either your suggestion that I don’t know my Nietzsche texts was sincere, in which case it’s rude in its presumptuousness and lack of generosity (i.e., “clearly you can’t have a real argument worth engaging, so I have to assume you don’t know the material), or it’s just plain rude.

Anyway, I’m still going to try to play nice, but I think you should consider the possibility that you could be more charitable in your approach. In your reply to my argument, you haven’t directly addressed the argument, but rejected the conclusion on behalf of a second, independent, new argument. I’ll try to infer a version that would address my argument, and you can correct it if necessary.

It’s very unclear to me, but I think your claim is that the paradox of eternity in time found in the Christian doctrine of incarnation is so important to K that it’s a necessary feature of faith. I disagree, but let’s assume so. If so, then it is either a feature of the subjective relation or of the object of faith. If it’s a necessary feature of the object (I must believe, e.g., in a god who became man, thus eternity entered time), then you can reject my premise 2.

However, my premise 2 isn’t a gloss, it’s just literally what K says. So you can only reject it by arguing that K is inconsistent. Moreover, you’d also have to reject K’s explicit claim that a pagan worshiping an idol can be in faith, which needn’t involve the parodox of eternity in time. On the other hand, just as you could conceivably finesse the pagan example to make the temporal paradox a feature (maybe any pagan deity’s greatness implies belief in its essential infinite nature…), so I can finesse my other examples: worshippers of reason don’t just see it as an accidental feature of human thought processes, but a deep metaphysical unity between human thinking and the deep structure of reality itself, a structure that is itself infinite and outside time, but made finite in the human mind in the operation of knowledge, etc.

In other words, if the temporal paradox is a necessary condition of faith, K contradicts himself. And even if so, any object of faith can in principle contain that paradox, you’d have to argue the individual case, you can’t assume that Christian doctrine is the only exemplar.

But to my mind this is beside the point. I don’t think K considers the temporal paradox a necessary condition of faith. It’s crucially important to emphasize it as an essential element of Christian doctrine, in order to argue against rationalist conceptions of Christian faith. It’s a strategic position: when a Christian says you ought to believe because the history checks out, or because read Hegel’s logic, K says nonsense, the claim that eternity entered time is repugnant to reason, if faith in relation to Christianity is possible, the incarnation proves it is only through granting a reality higher than reason.

So the incarnation is important as an insurmountable obstacle to reason, making Christianity a good example of why faith must take the form K says it does. Christianity is the test case, and the one relevant to his audience, not the defining case. It is not equivalent to saying this particular paradox is necessary to any kind of authentic faith.

Yan 08.22.16 at 3:54 pm

Holbo 34, as I suggested earlier, I don’t think Charlie Brown works as the last man. The implied author of Peanuts sides with CB, so he cannot be presenting him to us as a negative ideal, that is, as an ideal in contrast to which he thinks there is a higher, achievable type. The lesson of CB is that higher types do not and cannot exist. CB is not the last man, but everyman, humanity as such. Not the last but the first and only.

He represents not a critique but an affirmation: CB in fact passes the test. He not only wills the return of his existence, he wills it in the exact same form. He knows, and we know he knows, and Schulz wants us to know that he knows, that Lucy will pull the football again. He pretends to “hope” otherwise, but every event in the strip, every event in his life and–most importantly–his every reaction to those events (always a sigh, never gnashing teeth and cursing, or at least never convincingly, rarely surprise or anger) tells us he knows that his life will continue exactly as it has, and he chooses to live it anyway.

He hasn’t passed the test in the abstract, but in practice. The strip consists of the same events, over and over, and his response should be taken literally: grief is good, it is better than nothing. He is, in his way, a true overman, since he defies N’s idealistic belief that “man would rather have the void for a purpose than be void of purpose”. He is free of purpose, like a stoic who achieves ataraxia without needing to believe in reason. He may be a Camusian sisysphus, or a Simone Weil.

Yes, maybe Shulz is preoccupied with the fate of the small man. Because he loves him, because he sides with him, and because he believes we are all him, and that the overman and the small man are ultimately one and the same (it occurs to me that this is the heart of John Williams’ novel Stoner, too). That makes him no more a Nietzschean than Nietzsche’s preoccupation with nihilism makes him a nihilist.

ZM 08.22.16 at 4:12 pm

LFC,

I think Peanuts is humorous. I haven’t read it for ages, but I would be surprised if I started reading it again and found it pessimistic and the characters all unbearable. I think I would still find it humorous. I don’t think you can really say its pessimistic due to one or more of the characters. Its like saying The Gilmore Girls is pessimistic due to Paris Gellar or some other character. There is actual comedy I find too mean or dark etc to be enjoyably funny, but not Peanuts when I last read it, and I don’t think I would now find it very pessimistic and full of unbearable characters.

Yan you can’t take the jokes out of a comic strip so it fits your argument and then say its like Lord Of The Flies.

I think that Kierkegaard’s views on pagans are kind of redundant now outside of the context of 19th C and early 20th C missionaries.

Kierkegaarde seems to have a particular Lutheran approach to the issue of the salvation of pagans based on him asserting if a pagan has faith in the “idol” they worship it counts as faith, compared to a nominal Lutheran who actually doesn’t have faith in the God he is praying to. This seems to be related to the importance of faith for salvation in Lutheranism, whereas in other denominations faith doesn’t have the stand alone importance it does in Lutheranism.

But I think Kierkegaard’s thinking on this is outdated now. Most religious charitable organisations these days don’t even think that the “pagans” they assist are damned if they don’t convert them. And its not really the done thing to call people’s spiritual beliefs “praying to idols” these days and its also probably paternalistic concluding if a someone “in a pagan land” has true faith placed in a mistaken belief in an idol then they go to Christian Heaven. Its not really respecting other people’s spiritual beliefs.*

*And I disagree with Yan that Satanism is a proper religion you need to respect someone’s beliefs in or their covenants with Satan or whatever.

John Holbo 08.22.16 at 4:40 pm

“John, I apologized for my earlier rudeness. Either your suggestion that I don’t know my Nietzsche texts was sincere, in which case it’s rude in its presumptuousness and lack of generosity (i.e., “clearly you can’t have a real argument worth engaging, so I have to assume you don’t know the material), or it’s just plain rude. ”

I assure you I am only concerned that a pure diet of ‘word salad’, as you put it, will not prove sustaining.

“Holbo 34, as I suggested earlier, I don’t think Charlie Brown works as the last man.”

I’m not suggesting Charlie Brown is the Last Man. (Perish the thought! Sorry not to have warned against that misunderstanding. It literally had not crossed my mind.) I’m suggesting he is the small man, the broken specimen, whose recurrence would make the prospect of Eternal Return disturbing and perhaps intolerable. Not the same fellow (although, yes, they could be mistaken for another from a middle distance.)

“That makes him no more a Nietzschean than Nietzsche’s preoccupation with nihilism makes him a nihilist.”

Ah, I think your confusion here is due to mistaking mild hyperbole – it is a comment box, after all – for universal assertion. I was not seriously committing to the thesis that every “Peanuts” strip expresses a Nietzschean thesis or anything of the sort. But the one I was referencing seems Nietzschean. (Nor am I saying that Schulz is a committed Nietzschean, I might add. It doesn’t seem likely. Nor a Schopenhauerian.)

On to K.

“If it’s a necessary feature of the object (I must believe, e.g., in a god who became man, thus eternity entered time), then you can reject my premise 2. ”

Yes. I reject the premise on that ground. See, for example, The Sickness Unto Death:

“Only the Christian knows what is meant by the sickness unto death.”

And why is that? “If a human self had itself established itself, then there could be only one form: not to will to be oneself, to will to do away with oneself, but there could not be the form: in despair to will to be oneself.”

And: “The formula that describes the state of the self when despair is completely rooted out is this: in relating itself to itself and in willing to be itself, the self rests transparently in the power that established it.”

The power that established it.

I’m not denying that it could be some pagan god – far be it from me to labor to establish K’s Lutheran bona fides – but it is not the self. There can be no self-worship-as-faith, per your suggestion above. Nor reason-worship. K. thinks it would be plain silly to suppose his existence is established by the power of pure reason.

“I don’t think K considers the temporal paradox a necessary condition of faith.”

I think he does. This is extremely important to him. But it’s too late at night to pursue the matter textually.

Let me say how delighted I am that we have moved from Bunny Wunnies to The Sickness Unto Death. Wouldn’t it be something if it turned out that Helen Sweetstory was another Kierkegaardian pseudonym?

John Holbo 08.22.16 at 4:43 pm

“Because he loves him, because he sides with him, and because he believes we are all him, and that the overman and the small man are ultimately one and the same …That makes him no more a Nietzschean than Nietzsche’s preoccupation with nihilism makes him a nihilist.”

Nietzsche thinks the overman and the small man are one and the same. So if Schulz thinks that then he actually is a Nietzschean, which hadn’t really crossed my mind. But you might be right.

LFC 08.22.16 at 5:19 pm

ZM @37

I didn’t mention Lord of the Flies; Yan did.

Yan 08.22.16 at 5:20 pm

ZM 37, but of course I can take the jokes out to make my point. The point was not that the jokes are extraneous but that a comic strip isn’t reducible to them and they can blind us to its other aspects. Like good literature, a good comic strip creates a world, and that world is as crucial to understanding its meaning as its jokes. I agree that Peanuts is just plain funny, and often not in the least dark in its humor. It is *also* often dark, and often dark in its humor. In the early ones, the punch line is often literally a punch, like the end of a Zen koan. When we remember to include the picture of the world it presents–and temporarily ignoring the jokes is just a way of getting the rest of the strip’s world into focus–we see that in the Peanuts universe, every character revolves around Charlie Brown as the dark star or black hole that moves it. That is why the Gilmore Girls comparison is inapt: its universe revolves around Rory, that fact completely changes how we interpret its relations and participants.

I’d add that in my last posts, I’ve suggested a somewhat less pessimistic interpretation, closer to Camus or Weil than to Schopenhauer. In any case, it is a nuanced, heroic kind of pessimism. What I call pessimism here–the belief in the inevitability and prevalence of failure, cruelty, suffering, and solitude, but one which is compatible with warmth, affection, humor, and moments of joy–may not be what you mean by pessimism.

Another way to put it is that Schultz thinks life is good despite suffering. I consider that pessimistic in the sense that optimism is a belief that real, lasting progress can be made against suffering.

Yan 08.22.16 at 6:39 pm

John 38, Although I’ve apologized and had assumed you’d accepted the apology, my rude comment from my first post eternally recurs in yours. I don’t quite get your comments about it, perhaps you intend to reverse the charge against me? No matter, I’m happy to continue playing nice.

On N, I think we’re talking past each other, you debating the details of how Nietzsche maps onto Peanuts, and me debating the value of those details, however they’re mapped. You’re reading Peanuts through Nietzsche’s concepts, but I’m asking: does Schultz value those concepts in the same way, is reading through rather than in comparison and contrast to N’s concepts justified? Whether CB is the last man or the small man, you see him through Nietzsche’s eyes as what must be, with difficulty and regrettably, affirmed in the eternal return. But in doing so you fail to see CB through CB’s own eyes and, likely, through Schultz’s eyes. We see the Peanuts universe from outside, from N’s perspective, and in doing so from the start defuse the possibility that Peanuts’ perspective might deeply challenge rather than confirm N’s universe.

On the matter of our different interpretations of N, I suspect they’re bassed on rather foundational interpretative claims that are too deep to fruitfully debate here, but I’d at least insist we both have rather eccentric takes in comparison to the scholarly consensus or norm. (That, contrary to what ZM seemed to imply, it’s not my takes alone that are provocative or highly controversial). Would you admit, for example, that your view that “Nietzsche thinks the overman and the small man are one and the same” is not a very common one among, probably an outrageous one to many, Nietzsche scholars? Not wrong for that reason, of course, though I certainly disagree.

I have a sense that our deep differences here are in part–as with Kierkegaard–a reflection of which texts and topics we take to be central. You seem to give a lot of weight to roughly middle period works like GS and Z whereas I find those most enlightening–as largely a critical philosophy only anticipating a positive project in the future–when read backward, in light of the later texts like BGE, GM, and especially TI, EH, and A.

On K: you accepted my interpretation that you’re rejecting premise 2 without discussing the further point I made: that such a rejection is incompatible with K’s constant stress on the how rather than the what and his very strong, provocative claim that subjectivity is truth. Do you think he’s inconsistent here, or that he only means what he says when you agree with him?

As for whether the temporal paradox is necessary to faith, I think your choice of text does too much work. It’s much more plausible when looking at Sickness Unto Death than, say, Philosophical Fragments or Concluding Unscientific Postscript.

But it’s curious that your support for the claim is a passage about the self that doesn’t mention either Christ’s incarnation, temporality/eternity, or reason, which were the issues of dispute. In any case, the statement that the self rests in the power that sustains it tells us nothing that excludes faith in self or reason–provided we are talking not just about any cult of self or reason, but one that conforms to K’s picture of the subjective relation of faith. Someone who has “faith” in K’s sense in relation to the self must see the self as something higher than his or her own self-understanding, as something that she evaluates as the greatest good and law not out of rational assessment of her particular qualities but out of faith, out of the need and demand for an absolute beyond rational comprehension or questioning. It would be no ordinary egoism, but one which distinguish a believed absolute self from the temporal one, and places the latter under the absolute authority of the former. (Perhaps Stirner or Fichte might approximate something like this…)

Let’s be blunt: K’s temporal paradox is not religious but philosophical, and just Kantianism: the absurd is that in knowledge of any object the absolute, the eternal, the Kantian thing in itself exist temporily, subjectively, as phenomenon. The self existing in the power that sustains it is just the self as subject of phenomenal experience existing in the power of the noumenal object which, qua noumenal and unknown, might well be anything, God, the devil, Descartes’ evil genius, a stack of turtles, or the Fichtean ego or Schopenhauer’s will.

The point of faith is precisely the Kantian, philosophical and in many respects anti-religious claim that “the power that sustains” is noumenal reality, thus by definition is unknown, inaccessible to reason, and necessarily both an object of faith and an undefinable object. (In Philosophical Fragments he calls it the “absolute paradox” of the “absolute unknown”, about as far from any kind of religious doctrinal conditions as you can get.)

If K were trying–and I see no evidence that he does–to give us a negatively determinate object of faith in the Cartesian fashion (instead of “god” is not attribute or finite, “god” is paradox, eternity in time, non-self, non-reason) he would fail by his own criteria to have faith, he would rely on reason to negatively delimit faith’s object, to know it rather than to believe it.

Of course K doesn’t think reason is the support of existence, but his point is that faith is the faith that there is something that supports our existence, and what object we choose to insert in that blank is where “subjectivity is truth” comes in: how we treat the object, not which object we choose, determines faith and non-faith. In the case of reason, as I explained in my earlier post, to believe that reason gives us access to the noumenal world, that it is not accidentally reality to truth but essentially so, is paradoxically to give up reason in relation to reason, to have faith in the foundational proposition that the rational is the real, even as upon that faith we establish all *other* claims through reason. The point is that the foundational claim about reason is made in faith, not from reason, in that way we treat reason as the support of existence, we believe, probably falsely, that it is so. But this belief is no more ridiculous to K than the belief that God is, for both are rationally absurd articles of faith about an absolutely unknowable noumenal world in itself.

Yan 08.22.16 at 7:59 pm

Hi John, my last comment seems to be stuck in moderation. Any way you can push it through?

ZM 08.23.16 at 12:55 am

Yan,

“Let’s be blunt: K’s temporal paradox is not religious but philosophical, and just Kantianism: the absurd is that in knowledge of any object the absolute, the eternal, the Kantian thing in itself exist temporily, subjectively, as phenomenon.

The self existing in the power that sustains it is just the self as subject of phenomenal experience existing in the power of the noumenal object which, qua noumenal and unknown, might well be anything, God, the devil, Descartes’ evil genius, a stack of turtles, or the Fichtean ego or Schopenhauer’s will.

…

The point is that the foundational claim about reason is made in faith, not from reason, in that way we treat reason as the support of existence, we believe, probably falsely, that it is so. But this belief is no more ridiculous to K than the belief that God is, for both are rationally absurd articles of faith about an absolutely unknowable noumenal world in itself.”

Can you establish Kierkegaarde is in fact asserting these things with quotes?

I feel like you are attributing something to Kierkegaarde which I find it very difficult to believe he is asserting.

You mention Descartes, my reading of Kierkegaarde is limited, but actually one thing I do happen to know about Kierkegaarde is he thought Descarte’s conclusion I Think Therefore I Am is a tautology — If you have an I doing something, the I exists. Necessarily.

He actually brings this up sort of in the passage we are disputing. He says existence is not the same as thinking.

I can’t really understand why you say belief in Descarte’s evil genius scenario can be in any way correlated with faith?

Isn’t the scenario taking Descartes into a place which is the opposite of faith?

It is a scenario that is specifically about very extreme doubt, not faith.

Its fresh in my mind since I commented about it the other day in relation to some Buffy fan fiction in a thread which reminded me of Descartes’ evil genius scenario.

Descartes uses reason to free him from the extreme doubt of the evil genius scenario — hence I Think Therefore I Am — so doesn’t this particular example actually highlight the different nature between faith and reason?

This is something that Kierkegaarde himself looks at in the text. The text is about objective kinds of reflection and subjective kinds of reflection, and he looks at how reason or objectivity can be security against madness.

“For this reason the objective way is convinced that it possesses a security that the subjective way does not have. It is of the opinion that it avoids the danger that lies in wait for the subjective way, and at its extreme this danger is madness.

In its view a solely subjective definition of truth make lunacy and truth indistinguishable. But by staying objective one avoids becoming a lunatic.

However, is not the absence of inwardness also lunacy? It is true that subjective reflection turns inward, but in this inward deepening their is truth. Less we forget the subject, the individual, is an existing self, and existing is a process of becoming.

…

…thinking and being are not automatically one and the same. If the existing person could actually be outside himself, the truth would then be something concluded for him.

However for the truly existing person, passion, not thought, is existence at its very highest: true knowing pertains essentially to existence, to a life of decision and responsibility. Only ethical and ethical religious knowing is essential knowing. Only truth that matters to me, to you, is of significance. ”

Kierkegaarde clearly sees subjectivity as important — but you can see he specifies “ethical and ethical religious” forms of knowledge as being the only essential forms.

So I find it really hard to follow your thinking about the text.

How is Kierkegaarde in this text we are looking at saying that reason, or Satan worship, or Descartes evil genius are examples of faith?

I can see what Kierkegaarde means with the example he gives of a person who lives in a “pagan land” praying to an “idol” (apart from its very obviously outdated now) — but I can’t see how this applies to reason, Satan worship, or Descartes evil genius?

ZM 08.23.16 at 12:56 am

Sorry LFC, I didn’t mean to make it sound like I thought you said Peanuts was like Lord Of The Flies.

LFC 08.23.16 at 1:12 am

@ZM

Actually that was my fault, I was reading too quickly, missed your attribution to Yan. No problem.

p.s. Just saw this headline in WaPo: woman who was the real-life inspiration for the Peanuts character ‘the little red-haired girl’ has died. (I didn’t copy the link.)

John Holbo 08.23.16 at 1:58 am

“On N, I think we’re talking past each other, you debating the details of how Nietzsche maps onto Peanuts, and me debating the value of those details, however they’re mapped. You’re reading Peanuts through Nietzsche’s concepts, but I’m asking: does Schultz value those concepts in the same way, is reading through rather than in comparison and contrast to N’s concepts justified?”

No, I’m not reading “Peanuts” ‘through Nietzsche’s concepts’. I’m reading “Peanuts”.

(I think you are – in the words of Atomic Robo – simultaneously over and under thinking all this, Yan.)

I’m reading what the strip says. And noticing that it plainly asks the same question Nietzsche asks, and says is his most central thought. And Charlie Brown answers in the way Nietzsche predicts. Do you have some way of reading the strip so that it actually doesn’t pose the famous Nietzschean question, and provide the predicted answer? (It’s too bad Schulz didn’t do a follow-up post the next day, in which Lucy asks Snoopy the same question and he just kisses her on the nose and dances. And she looks horrified.)

“but I’m asking: does Schultz value those concepts in the same way”

You seem to be reasoning on the basis of a suppressed premise: if there is any way in which the strip, or its author, is not Nietzschean, then there is no way in which it is Nietzschean, ergo it is wrong to say ‘this “Peanuts” strip is Nietzschean.’ I deny this premise on the grounds that it is non-obvious, to put it mildly. It’s so obviously non-obvious that I am a bit provoked to try to provide a proof of its non-obviousness (that is yet more obvious.) But here goes:

You write “Hence the deep humanity and empathy, more in keeping with Schopenhauer’s ethics than Nietzsche’s condemnation of pity.” And: “Peanuts has important similarities to Schopenhauer: a pessimistic view of life and human nature in which Charlie brownish grief is inevitable, in which humans are essentially unbearable to each other, and the only good is to lessen each other’s suffering as much as possible.” And yet! And yet! Schopenhauer never wrote a book entitled “The World As Will and Warm Puppies”. Nor would it have been in his nature to do so. If you can see that there are ways in which “Peanuts” both is and is not Schopenhauerian, you ought to be able to see, by parallel reasoning, that there can be ways in which “Peanuts” both is and is not Nietzschean.

“On the matter of our different interpretations of N, I suspect they’re bassed on rather foundational interpretative claims that are too deep to fruitfully debate here, but I’d at least insist we both have rather eccentric takes in comparison to the scholarly consensus or norm.”

I don’t actually think my interpretation is that eccentric. But let it pass.

On to K.: here I am detecting some burden-shifting and goalpost-moving, which I am inclined to resist. You are saying that it should be possible to construct such-and-such a view, consistent with K’s commitments. I am sure K would be profoundly unhappy with that result. A Christian theologian whose theologic implies unintended results he would reject, or be disturbed by, should he become aware of them, is not therefore either an atheist, crypto-atheist or an atheist-in-denial, I think.

“But it’s curious that your support for the claim is a passage about the self that doesn’t mention either Christ’s incarnation, temporality/eternity, or reason, which were the issues of dispute.”

This seems weak to me. Just because he doesn’t mention it in literally every sentence, only in quite a lot of them, doesn’t prove that it actually wasn’t that important to him.

What I mean by burden-shifting is this: you seem to be challenging me to knock down your alternative reading of K as a potential reason or self-worshipper. Well, as K would say: first build the tower. It doesn’t seem to be built yet. Then we can see about knocking it down.

I’m off to teach!

Doug Hudson 08.23.16 at 1:03 pm

Incidentally, anyone who thinks Peanuts was just humorous needs to read the strips from the 50s. Some of those comics are so dark that I’d almost hesitate recommending them for children, except that I doubt many children would grasp how dark they were.

The one where the kids are playing thermonuclear bomb, for example. Or the one where Charlie Brown lists his war comics (revolutionary war, civil war, WWI, WWII, korean war), and then comments that he “isn’t looking forward to the next one.”

Or the very first strip, with its classic ending: “Good ol’ Charlie Brown! How I hate him!”

dSmith 08.23.16 at 5:12 pm

Well… I was going to say I saw a duckie and a horsie, but I changed my mind.

LFC 08.25.16 at 1:53 am

Doug Hudson @48

Interesting re the strips from the ’50s.

The fear of global nuclear war in the ’50s and its intersections w culture (low, high, and medium/midbrow) is something that’s been much written about, so I guess it’s not too surprising, but still interesting.

William Burns 08.25.16 at 2:03 am

Anderson, Indiana is the headquarters of the Church of God of Anderson, Indiana, a fundamentalist group Schulz was involved with in his fundamentalist days. In case anyone was wondering.

robotslave 08.25.16 at 8:50 am

dSmith @49 has won this week’s Commenting On The Internet Challenge. Thank you for your interest, and please check back regularly for the announcement of our next contest.

John Holbo 08.25.16 at 8:51 am

Yes, dSmith wins the thread.

John Holbo 08.25.16 at 8:52 am

“Anderson, Indiana is the headquarters of the Church of God of Anderson, Indiana, a fundamentalist group Schulz was involved with in his fundamentalist days. In case anyone was wondering.”

That’s an amazing tidbit, actually!

Comments on this entry are closed.