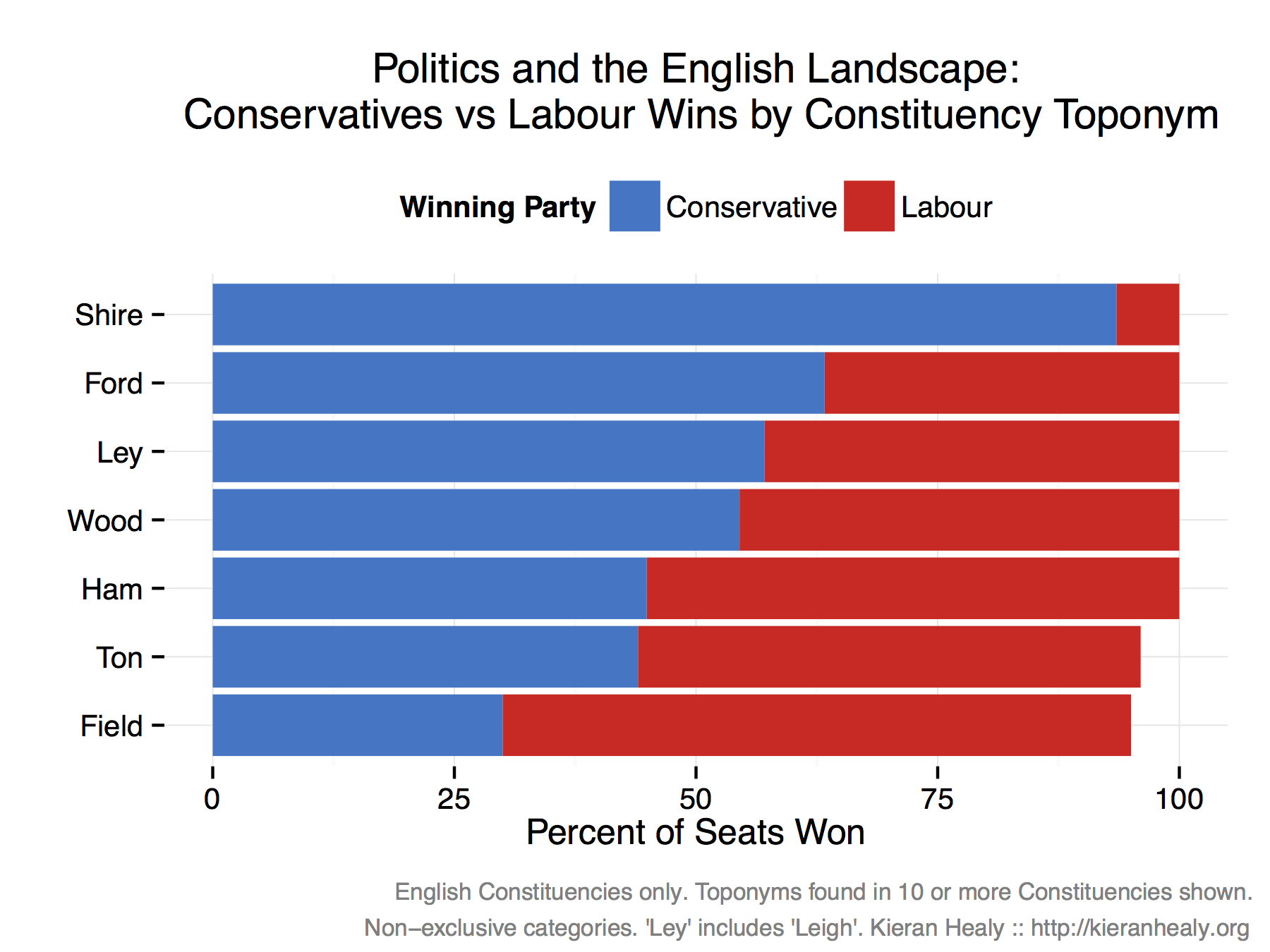

I’m still playing around with the [UK Election data](http://kieranhealy.org/blog/archives/2015/05/09/who-came-second-in-the-uk-election/) I mapped yesterday, which ended up at the Monkey Cage blog over at the [Washington Post](http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/monkey-cage/wp/2015/05/10/what-the-runners-up-tell-us-about-britains-election/). On Twitter, Vaughn Roderick posted a [nice comparison](https://twitter.com/VaughanRoderick/status/596967966647971840) showing the proximity of many Labour seats to coalfields. That got me thinking about how much the landscape of England is embedded in its political life. In particular, what do the names of places tell you about their political leanings? I looked at English constituencies only, and searched constituency names for some common toponyms like “-ham”, “-shire”, “-wood” and -field”. Then I looked to see what proportion of seats with these features in their names were won by the Conservatives and Labour. For simplicity of presentation, I omitted the Liberal Democrats and UKIP who won a very small percentage of some of these seats. Here’s the result.

I think that’s rather nice. The Tories are the party of shires and fords, and to a slightly lesser extent of woodland clearings (-ley, -leigh) and woods. Labour meanwhile are the party of -hams (as in, a farm or homestead), of -tons (or towns), and of fields.

Note that some double-counting occurs, because the naming categories are not necessarily exclusive. I did focus on suffixes, so for example “Northampton” would be counted as a -ton but not a -ham, and constituencies with ‘ton’ in their name but not at the end of a word would not be counted in that category.

{ 15 comments }

digamma 05.10.15 at 10:16 pm

The correlation with coalfields reminds me of how, in the US, the blue-red map is impacted by an ancient geological formation.

Tom Slee 05.10.15 at 11:23 pm

“-ley” may also be worth trying (Batley, Bramley etc).

Kieran Healy 05.10.15 at 11:38 pm

Tom—good call. I’ve added it.

Tom Slee 05.10.15 at 11:46 pm

Thanks. I expected it to be more red than blue.

Tim Silverman 05.11.15 at 6:12 am

What about “-by”, “-thwaite” and “-thorpe”?

Niall McAuley 05.11.15 at 8:29 am

What about Torpenhow Hill?

Harald K 05.11.15 at 10:19 am

Hobbits confirmed to vote Tories.

Ben Glasson 05.11.15 at 1:20 pm

Perhaps -chester, too?

ajay 05.11.15 at 4:36 pm

Is “-don” a variant of “-ton”? Might be worth adding that too.

chris y 05.11.15 at 6:21 pm

Burgh/Borough/Brough?

Jeff R. 05.11.15 at 6:36 pm

Thinking about -don and whether the particular case of London might dominate an otherwise opposite trend in other such cities leads me to wonder if that isn’t already happening in -ham… (And wouldn’t happen in -chester/-caster/-castle, for that matter.)

Colin 05.12.15 at 3:39 am

Most ‘-shire’ constituencies are presumably of the ‘North East Bedfordshire’ variety, i.e. chunks of counties that are so dispersed in population that there’s no settlement prominent enough to name them after. Anything that doesn’t end in ‘-shire’ is unlikely to be named after a county, and consequently more likely to be named after a settlement. At the other end, a name like ‘X South’ is usually a good sign that the constituency is highly urban, part of a conurbation with a six-figure population. It would be interesting to see how Lab/Con did in constituencies where a compass direction is the last part of the name versus the first part.

Colin 05.12.15 at 4:13 am

Actually, it occurs to me that ‘town-shire’ is somewhat localised as a traditional naming scheme for counties. There are three large zones where this naming scheme is absent: the West Country, the far north of England (anything to the north of Lancashire and Yorkshire) and most prominently an ‘Anglo-Saxon petty kingdom region’ in south-eastern England (the boundary runs in a wavy line from the Wash to the western edge of West Sussex). I don’t know what this means for the preponderance of Tories, though.

chris y 05.12.15 at 12:00 pm

Actually, it occurs to me that ‘town-shire’ is somewhat localised as a traditional naming scheme for counties.

Alternatively, it’s localised to Wessex, where the shire system originated, and Mercia which was annexed to it by Edward the Elder. The “Anglo-Saxon petty kingdom region” tended to keep the names of the petty kingdoms or their subdivisions (plus Lincolnshire where the petty kingdoms survived as Parts. North of the Don was all Northumbria (or Alba) from Aethelstan until some time after the Norman conquest, so different rules apply.

How does -wick/-wich pan out in this analysis? I ‘d guess significantly Tory.

Ogden Wernstrom 05.12.15 at 7:26 pm

-sex might be worthy of investigation.

Comments on this entry are closed.