I’m reading two books called Wit’s End at the same time, which deserves a prize, or I am committing Yvor Winter’s Imitative Fallacy. The first is witzend [amazon associates link]. The second is Wit’s End: What Wit Is, How It Works, and Why We Need It[amazon], by James Geary.

In order: witzend was Wally Wood’s baby. Wally Wood [wikipedia], if you don’t know, is one of the greats. He did his most classic work in the 50’s, in MAD and on EC Comics Weird Science and Weird Fantasy stuff. (Fantagraphics has been putting out a lot of good stuff, collecting his stuff.) I consider his “22 Panels” page to be a stand-alone masterclass in comics composition. I am not alone.

witzend was Woods’ independent, creator-controlled, underground/proto-Comix last attempt to achieve escape velocity from the commercial comics gravitational field. (Per the subtitle of ’22 panels that always work’, he thought a lot of the stuff he had to do was boring and lame.)

witzend launched in 1966. I love, love having the complete run in one volume. I confess, I don’t really like it.

On the one hand, the contributors list over the years is amazing. I love it! A lot of the old EC crew, Wood himself, Will Elder, Al Williamson; also, a lot of fantasy illustration greats: Jeff Jones (later, Jeffrey Catherine Jones), Frank Frazetta, Bernie Wrightson. Also, Will Eisner. There’s lots more. (Some I don’t like, of course. Bode Vaughn. Meh.)

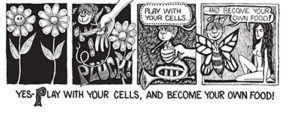

Per my recent Art Young posts, it’s delightful to find key nodes where lines of graphical influence meet and criss-cross. witzend is that to an astounding degree. In issue #3, in 1967 we have Steve Ditko introducing his Randian Mr. A alongside a young Art Spiegelman, going through a brief, ‘flower power’ phase. witzend is truly where comics greats got to play with their own cells and become their own food.

At the same time, darn it, the stuff isn’t very good, in my opinion. I like looking at the pictures by all my favorite artists. But, as comics, witzend seems to me mostly a failure. What went wrong? It’s kind of interesting to diagnose.

Witzend had a ‘no-policy’ policy. Wood wanted to be free, and he wanted his co-contributors and collaborators to be, likewise, free to follow their creative dreams where they might lead.

The problem, in Woods’ case, is this led to mediocre decisions. Here is Art Spiegelman, describing where his head was at.

So the story goes, the reason Power Girl has big ones is Wally Wood was drawing her, and bored, and he just started making ’em bigger and bigger, wondering when someone in editorial would notice. Evidently it took a few issues.

Wally Wood drawing chicks and sort of noodling around with half-digested notions of Freud, plus second-hand Tolkien high fantasy tropes is just not great comics. It lacks vision and direction.

I feel that the same is true for a lot of the stuff in witzend. When they were let loose … they didn’t have a lot to say. Graphically, a lot of it is really beautiful, but no one involved seems to be fired with any brilliant idea about what new worlds comics should conquer now. Some of it is very retro. Edgar Rice Burroughs sword&sandals&sorcery stuff. Some of it is random hippie. Some of it is pretty sour in the toxic masculinity department – but not much. Mostly it just kind of drifts.

It’s like Wood and co. got to pretend they were they pent-up geniuses, when the squares at Marvel and DC made ’em obey the Comics Code. But it turns out that they did better work pent-up. It’s like the final episode of LOST. Wood was so much more magic when you could imagine all the wonderful stuff he could have done if they’d let him.

It’s true that witzend paved the way for RAW and other comix and underground stuff. There’s other stuff coming, and Wood is rightly remembered as godfather to that. I get why everyone involved wanted freedom. But it feels … exhausted.

Thinking this made me go back and look at old issues of MAD from the 50’s. Wood did great, funny stuff back then. Maybe he was just younger? But I feel that it’s the ‘for kids’ constraint on MAD that somehow makes it great. It’s for kids … and it isn’t. It’s amazing how many of the jokes in MAD are a bit over kids’ heads, but kids like that, and it wouldn’t be nearly as good for kids if it didn’t have the bits kids probably miss. Do you have some bit from MAD that just blew your mind and, even now, you can call all that back? I do. I was over at my friend Evan’s house. I must have been 9. His older brother had a stack of old MAD‘s and one of them had “Mole!” in it. It creeped me out. Especially the bit about how he dug his way out of jail, using only his own nostril hair! It’s gross-out humor for boys, but there is something genuinely surreal about it. And the Will Elder art is great (and gross).

The same goes for a lot of the comics stuff going on in the 60’s and early 70’s that Wood was creatively impatient with. Let me tell you what is, I think, the funniest thing Wood has ever drawn. It’s on his Wikipedia page. Daredevil #7. DD gets his red suit for the first time and fights the Sub-Mariner. Cool! But here’s the thing. The writer – I’m looking at you, Lee – has decided the way to make Namor seem regal is to make him like the Hulk, but for not-waiting. Namor has decided he is going to sue all mankind and he needs a lawyer, so he picks Matt Murdock. But, to show how regal he is, Lee writes him as impatient at every stage.

Then he smashes Matt’s desk for emphasis and, at the conclusion of the business meeting, he leaves straight through a brick wall. And – better! – the women are all oohing-and-ah-ing at his manifest regal bearing, like the thing modern women fantasize about is a guy in a Speedo who can’t be bothered to manage a revolving door.

I would pay good money for a series that was just Namor Destroys Buildings While Seeking Professional Services.

And, in a nutshell, this is a big part about what makes great Marvel Comics great: the sheer, naive goofiness of it. So many subsequent styles of humor grow out of this sort of thing. So the irony is that witzend was trying to be more witty, by being more adult, but ended up being less funny, by letting go the childishness.

At this point I’ll shift over to Geary’s Wit’s End. Honestly, I haven’t decided yet whether it has anything to say for itself. But here are a few snips.

Words like “outwit” and “quick-witted” hint at the link between wit and knowing, while words like “dimwit,” “nitwit,” “witless,” and “unwitting” hint at the link between wit and not knowing. We have our wits about us if we are street-smart, savvy, or shrewd. We live by our wits when we devise impromptu solutions to sticky situations or evade seemingly inevitable consequences. We can be scared out of our wits and, sadly, we can also reach our wit’s end.

Geary, James. Wit’s End: What Wit Is, How It Works, and Why We Need It (Kindle Locations 241-246). W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition.

True. We aren’t inclined to call Daredevil #7 witty because it’s so clueless, frankly. But witty people enjoy it precisely for that reason. It’s like the Rude Mechanicals’ bad play, in Midsummer (a thing I have been having some extramural fun with.)

Another:

“The reason for your complaint,” Schiller wrote, “lies in the constraint which your intelligence imposes upon your imagination . . . It is harmful for the creative work of the mind, if the intelligence inspects too closely the ideas already pouring in, as it were, at the gates. Regarded by itself, an idea may be very trifling and very adventurous, but it perhaps becomes important on account of one that follows it; perhaps in certain connection with others, which seem equally absurd, it is capable of forming a very useful construction. The intelligence cannot judge all these things if it does not hold them steadily long enough to see them in connection with the others. In the case of a creative mind, however, the intelligence has withdrawn its watchers from the gates, the ideas rush in pell-mell, and it is only then that the great heap is looked over and critically examined.”

Freud cites this passage in The Interpretation of Dreams to explain the way he believed people suppress troublesome or traumatic thoughts before they become conscious, and the way these thoughts slip past the mind’s sentries and into our dreams. He developed the technique of “free association”—sharing thoughts, fantasies, and other forms of ideation without first deliberating over them—to coax suppressed material from the unconscious. Uncensored access to associations, conscious and unconscious, is essential to wit … (Kindle Locations 597-608).

Half-true. Namor hilariously failing to navigate the doorways is a perfect metaphor. He is an idea pouring in, with absolutely no intelligence to govern its passage, leading to yet more absurdity. Yet, with the building of art reduced to absent-minded half-rubble by his pell-mell rush, a critical intelligence step in to pronounce it strangely perfect. And so various artists have, taking up the Marvel mantle, making good jokes and good comics ever since, after this stuff.

It’s not that there’s anything so Freudian about Namor’s penetrative progress. It really is the innocence of it. What if a child’s way of looking at the world came true? What if it made sense to hire a lawyer like this? What a senses-shattering world it would be?

I have long been meaning to write an essay about this stuff, taking off partly from one chapter from William Empson’s book on Pastoral. The Chapter on “Proletarian Literature”.

I’ll just quote a few key bits.

One idea essential to a primitive epic style is that the good is not separable (anyway at first level judgments) from a life of straightforward worldly success in which you keep certain rules; the plain satisfactions are good in themselves and make great the men who enjoy them. From this comes the ‘sense of glory’ and of controlling nature by delight in it. It is absurd to call this a ‘pre-moralistic’ view, since the rules may demand great sacrifices and it is shameful not to keep them; there is merely a naive view of the nature of good. (Both a limitation of the things that are good and a partial failure to separate the idea of good from the idea of those things.)

That’s Namor. It’s not pre-moral. His hilarious theory about how to hire a lawyer expresses an epically naive view of the nature of the legal good.

And:

The essential trick of the old pastoral, which was felt to imply a beautiful relation between rich and poor, was to make simple people express strong feelings (felt as the most universal subject, something fundamentally true about everybody) in learned and fashionable language (so that you wrote about the best subject in the best way). From seeing the two sorts of people combined like this you thought better of both; the best parts of both were used. The effect was in some degree to combine in the reader or author the merits of the two sorts; he was made to mirror in himself more completely the effective elements of the society he lived in. This was not a process that you could explain in the course of writing pastoral; it was already shown by the clash between style and theme, and to make the clash work in the right way (not become funny) the writer must keep up a firm pretence that he was unconscious of it.

As Empson notes, one of the most interesting features of the ‘pastoral’ genre is the way it invites mockery — not just the straight sort (though that); but a potentially refined, yet sentimental twist on itself. For example, the Rude Mechanicals in Shakespeare. Mock-pastoral, at the most basic level, consists of pointing out that ‘rustics’, far from speaking about important things in the best way, can be counted on to flub their lines in the worst way. Hence the preposterous play-within-a-play. Yet the play’s outer fairy tale frame — ‘best in this kind are but shadows’; ‘what fools these mortals be’ — affords the Mechanicals a paradoxical recovery of metaphysical dignity. As Empson remarks:

The simple man becomes a clumsy fool who yet has better ‘sense’ than his betters and can say things more fundamentally true; he is ‘in contact with nature,’ which the complex man needs to be, so that Bottom is not afraid of the fairies; he is in contact with the mysterious forces of our own nature, so that the clown has the wit of the Unconscious; he can speak the truth because he has nothing to lose.

Pastoral says the simple bumpkin can be wise as a king, because the important things in life are so simple. Mock-pastoral says the simple bumpkin can be as wise as a king because the important things in life are so complex (not even a king can understand.) Whenever we are at our wit’s end, we wish Namor’s approach could be right about whatever complicated thing it actually is, IRL.

(This post could be an apology for Trump, who Presidents the way Namor hires lawyers. But that would be a mistake. It’s important to recognize the metaphysico-political divide between mock-pastoral and ‘fake news!’)

{ 12 comments }

Alan White 02.18.19 at 5:05 am

Great post John.

I wish I could sit down with you and re-read all my Marvels, as I did when I wrote a poem about re-reading FF #6 and posted it in one of your threads. I’m not as informed as you about the genres and pastoral versus post-pastoral and all, but of course Wood and Ditko and Kirby et al have formed taut fibers in my oldish soul, and as I re-read comics I’ve saved for over half a century I’ve come to realize how much Stan Lee has been an influence on my thinking as much or maybe more than has Hume or Kierkegaard. Lee got to me much earlier and that I suppose that makes a big difference.

What Lee’s Spider-Man and FF did for me was to allow that frailty was normal–even to the supernormal. That frailty was often contrasted against the megalomania of a Namor or Dr. Doom or Sandman or Mysterio, so often cast as an epitome of an overconfidence about ability, goals, or unbridled zeal that ultimately mocked itself. That was a good lesson. If Marvel overall had one good lesson to teach that a Superman lacked or a Batman only at best implied–it was humility. DC tried to get to some of that recently with killing off heroes and the like, but it’s not at all the same. If I were to write an academic article about Marvel versus DC, it would be about the ascension of virtue ethics over deontology.

John Holbo 02.18.19 at 5:44 am

Thanks, alan! It’s good to stretch the oldish fibers, I find more and more.

John Holbo 02.18.19 at 5:50 am

I was discussing this issue on a board I’m on and someone else posted exactly the same thought I had about this DD issue (before I expressed it, but I had just thought it myself). We both thought: I would pay good money for a series about Namor just knocking things down, trying to procure professional services. It’s some Marvel a priori.

Matt 02.18.19 at 10:47 am

It’s like Wood and co. got to pretend they were they pent-up geniuses, when the squares at Marvel and DC made ‘em obey the Comics Code. But it turns out that they did better work pent-up.

Jon Elster has a paper on this in the arts somewhere. (I thought it was a chapter in _Ulysses and the Sirens_ but it doesn’t seem to be there. Maybe in _Ulysses Unbound_?) I read it and liked it, but no longer remember where it’s from.

My own take on this is in relation to Tarkovsky. I’ll claim that his work in the Soviet Union is better than his work after defecting for much the same reason. I mean, his last few films are not quite Yves Klein painting people blue and having them roll around on sheets of paper, but they are not really that far off, either.

Adam Roberts 02.18.19 at 10:50 am

Two posts in one and both great. I often come back to Empson’s Pastoral book: a bit weird and opaque in places (opaque in a oddly-specific-1930s-leftwing-crotchets sort of way perhaps) but also really brilliant. The chapter on Carroll’s Alice books is some of the best criticism ever written on that topic I think.

Does the Geary book talk about how ‘Wit’ in German means jokes in a way that isn’t really true of English ? (Freud’s Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious is, in the original, Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewußten). That seems pertinent to what you’re saying here, sort of.

John Holbo 02.18.19 at 12:39 pm

Hi, Adam,

“Does the Geary book talk about how ‘Wit’ in German means jokes in a way that isn’t really true of English ?”

Yeah, I was kind of skating over that in the post, trying to get past Freud to Empson.

alfredlordbleep 02.18.19 at 7:46 pm

Adam Roberts’ mention of Empson on Alice lead me to another aside (with a ref even to drawing)

drawings, intellectual life, chastity

Theophylact 02.18.19 at 9:58 pm

The late, great Galaxy magazine often had illustrations by Wood — and even by Don Martin.

William Timberman 02.19.19 at 3:23 pm

The parenthetical paragraph at the end is itself worth the entire price of admission. John Holbo doesn’t just palaver about wit, he actually offers us the thing itself. Theory and practice in harmony at last!

John Holbo 02.20.19 at 1:18 am

Glad you enjoyed it, William! Thanks.

Another Nick 02.20.19 at 4:38 am

Matt, I think his last film The Sacrifice was great, and not really what you’re describing.

https://youtu.be/AhiC9bcoriU

There’s only that and Nostalgia that were made ‘after’ he defected, and Nostalgia had been in the works for years, and was well-developed by the time he chose not to return to the Soviet Union.

It’s been a while since I’ve read this, but I don’t remember his life at that point (directing a 142-minute film, unable to see his son, dying of cancer) as being any less pent up.

https://monoskop.org/images/d/dd/Tarkovsky_Andrey_Time_Within_Time_The_Diaries_1970-1986.pdf

Matt 02.20.19 at 9:34 am

Hi AN – I’ve seen all of Tarkovsky’s films – and actually like them all. But, I do think that both The Sacrifice and Nostalgia (and even Zerkala, before that) were getting out of control artistically, if seen as film and not, say, performance art pieces, and tend to think that the lack of restrictions – from the Party, or a studio, or someone, was part of the problem. I don’t say this as _obviously_ true. (I’m not close to an expert on film or art more generally!) But that’s how it seems to me – that seen _as movies_, his earlier work was better, and a big part of why it was better was that it was more disciplined.

Comments on this entry are closed.