Josh DiPaolo is one of the most thoughtful and skilled teachers I know, and he has a fair bit of experience teaching online. So once I thought about this transition long enough to start feeling really overwhelmed by it, Josh was my first call. And he was generous enough to spend some time writing out answers to questions supplied by graduate students in my department. I’ve pasted our emailed “conversation” below.

One of my favorite things about Josh’s responses is his insistence that we bear in mind all the other ways that our students’ lives are difficult right now. Some of these are quite severe, but others are mundane and it’s fully within our control to avoid compounding the difficulty. For example, Josh reminds us that our students, just like us, are overwhelmed right now with emails. So especially in these early days, we should take extra care in crafting our communications to them so as to avoid the need for repeated follow-ups to correct or clarify. We can try to be a warm and calm voice for them, or at least work hard to avoid adding to their stress and anxiety.

There are lots of gems in here. Here’s one of my favorites:

“One bit of advice I’ve seen floating around seems right and relevant to this question. The idea is something like: ‘You’re not now teaching an online class. You’re moving your face to face class online.’ What this means to me is that the question at hand is not what’s the best way to assess student learning online. It’s more like: what’s the best (or maybe even just a good) way to assess student learning, given that half the semester was in person and that students enrolled in this class with certain expectations and that now I have to assess it using online tools in the context of a worldwide pandemic?”

Hi Josh,

Thanks for agreeing to answer some questions for us. We know you have a lot on your plate right now, as you too are making this transition mid-semester, so we’re especially grateful for your time. These questions come from our grad students, but I’ve done a little editorializing to give context and maybe save you a bit of time. (For example, in the first question, I took a stab at explaining a distinction that some folks might not be familiar with, which you can then add to or correct if you want.) Please just skip any questions that you don’t have thoughts about, and feel free to insert references to other work if that saves time relative to writing up a response in your own words.

- What are your views about the costs and benefits of synchronous vs. asynchronous instruction? [With synchronous instruction, we’re with our students in time even if not in place, interacting in a sort of virtual classroom, for example over Zoom. With asynchronous instruction, we provide materials for students to access on their own time and equip them to engage in learning activities and discussions without having to come together in space or time. This might involve setting up discussion pages on Canvas or uploading slides with audio voice-over. My understanding of the general best-practice guidance on this matter is that synchronous online instruction starts to lose its instructional value relative to asynchronous instruction—given existing technological and human capability—at around 17-20 students.]

First, I’ll tell you I’m going (nearly) fully asynchronous (exception: office hours. See below). I teach three classes, each with about 50 students. I’ve considered lots of different options. Fully synchronous: just Zoom the whole class at the usual meeting time. Mixed: Create lectures for students to study on their own time, and then meet at the regular class times for the sake of active engagement and interaction. That’s the benefit of synchronous teaching: it permits immediate feedback, live interaction between teacher and students, etc. It also facilitates communication about course logistics. But there are lots of reasons not to go synchronously, especially as the number of students increases.

There are obvious and less obvious practical reasons to go asynchronous in the present context. The obvious: students may not be available at a single time. The slightly less obvious: we don’t know how other instructors are transitioning their courses online. I care about being responsible and not overburdening my students; other instructors might have different priorities, or they might share those priorities but have much higher expectations than I do. We already ask students to do readings and coursework. But now students’ workload will increase, and it’s hard to estimate by how much: they now need to find their way around these new online classes, possibly do more reading if professors are just uploading notes/slides, watch videos and take notes on these videos, while maybe rewinding a bunch of times to make sure they got exactly the right words (something they can’t do with their time in the classroom), and so on. And they have to do all this in the context on a worldwide pandemic! Because I don’t know what other professors will ask of students, I am not assuming students will have as much time for my class as they would have had before; I’m definitely not assuming they’ll be on the same schedule they were before. I realize I almost never know what other professors ask of their students. But at the beginning of the semester, students have a choice about whether to take certain classes given those expectations. They don’t have a choice now; they’re stuck with whatever instructors throw at them. This makes me want to be very cautious about what I throw at them.

I’m thinking about how this consideration about time applies to myself too. It’s hard to estimate how much time it will take me to complete everything I need to do in this context. I think teachers need to avoid assuming they’re on the same schedule as before. Going asynchronous uses up a ton of resources. But even if you stay synchronous, you still might be answering more emails and managing your own stress and uncertainty about what’s happening in the world. [Note: As I finished writing this, the President declared a national emergency and LAUSD – one of the largest public school systems in California – announced it’s now closing its schools. I have a kid, in a different school district. I would hate to decide to make the class synchronous, changing things up on students in that way, only to change things again when I am no longer available during class time because I have parenting responsibilities during the day. Things are already confusing enough. I don’t want to make them more confusing by changing things up on my students again.]

In addition, it’s really hard to tell how much students will lose by not having the sort of synchronous experience we can actually offer them. I am absolutely in favor of face to face classes over online classes (especially online classes thrown together in a week). But a Zoom class is not a face to face class. It’s really, really easy to get distracted in Zoom classes when it’s easy to be anonymous. And Zoom etiquette and common behavior – mute the sound, mute your picture – make it easy to be anonymous. I was in a Zoom meeting with about 20 faculty (from across the university) the other day, and I was totally distracted. Checking my email, checking facebook (mostly for coronavirus updates), etc. Harvard students may be different; but it can already be difficult to hold my students’ attention in face to face classes where I can see exactly what they’re doing. It’s going to be harder to keep their attention when they can basically be anonymous/hidden and when they’ve got a ton of other online or other content they need to be consuming. Plus, Zoom doesn’t tend to pick up whiteboard content well. It does allow screensharing, so you might try to learn some new technology that allows you to mimic a whiteboard. (I think Zoom has this feature. I’ve heard it’s not great.) What I’d say about this is: be sure to consider the expected return on your investment. If you can see yourself using this technology again in regular circumstances, it might be worth it; if not, it’s probably not.

So: the costs of asynchronous instruction are loss of easy communication and some active engagement and face to face discussion. I think there are lots of benefits. But the thing I’m keeping in mind is that the appropriate comparison isn’t between asynchronous engagement and face to face engagement; it’s between asynchronous engagement and Zoom-ish engagement in the context of coronavirus.

- Do you have suggestions for facilitating student participation in the online format? [I think the questioner has in mind synchronous participation, but you might also remark on asynchronous alternatives if you see fit.] How, absent body language cues, can you gauge whether students are engaged? Are there learning activities that work especially well (or not so well) in this context?

Synchronous

I’ve never seriously tried synchronous participation. (Most of my experience in online teaching is teaching classes meant to be online classes. In those contexts, it’s not just practical reasons that favor asynchronous instruction; it can be more a matter of justice. But I’ll stay in my lane and leave that kind of consideration to Gina.) As I understand it, Zoom has the ability to break students up into groups. For the sake of reducing anonymity, I would think the smaller the better, with 3-4 students being about the ideal number. Zoom also has a “hand raising” function, poll function, and a chat function. So, if you go this way, you might play around with those. You might tell students to put questions they have while you’re lecturing in the chat area; this will be your chance to pretend you’re a professional Streamer, answering questions as you talk. In fact, I would strongly encourage you to strongly encourage students to participate with these functions while you’re lecturing. That will help keep them engaged. If you have few enough students, you might even mention students who are not participating by name. Not in a mean way. Just: “Jose I haven’t heard from you yet. Are you with me? What questions or thoughts do you have about X?” (To my mind, this is going way above and beyond if you have more than like 8 to 10 students.)

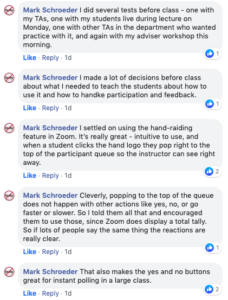

For what it’s worth, Mark Schroeder (USC metaethicist) had success with active engagement via Zoom in a class of 90ish students. With his permission, I screenshot his description and I’m sharing it here. I found it super helpful and inspiring. He wanted to clarify that this is his first time doing this and he’s experimenting here. Here’s what he said.

The question about which learning activities work well in this context is a good one. Since I’ve never done this, your guess is as good as mine. In my face to face classes, I often break students up into small groups to chat; in Zoom, it’s chaos when people talk over each other. So, unless you break students into groups using that function, activities have to be limited to one person talking at a time.

Asynchronous

If you go asynchronous, the limitations are obvious: no activities that require immediate interaction. For what it’s worth, posing the discussion questions you would pose in class, or perhaps ones that require even deeper thought, often works relatively well in an online discussion forum. Yesterday, I devoted my last face-to-face sessions with students to talking through our plans for the rest of the semester. I asked for tips on how to facilitate discussion online. Students who had taken online classes said they think discussion forums are totally fine. (I was surprised; I thought they’d think that was kind of boring.)

I make sure the questions are open-ended. Sometimes I just ask students to make their own original response, then comment on two others’. Sometimes I do “snowball” commenting (works best with small groups of students). I’ll order the students: 1. Gina 2. Jeff 3. Josh… Then Gina does her own post. Then Jeff does his post and comments on Gina’s post. Then Josh does his post and comments on the two before his. Now Gina comments on the last two posts. Now Jeff comments on Gina’s. Sometimes this works well because it can force students to keep returning to the thread; sometimes it annoys students because others aren’t participating. The nice thing about not doing a snowball, but still requiring students to comment on others’ posts is then they have to read a bunch of posts and do some thinking: “which of these posts should I comment on?” That thinking is important learning.

Rather than making the post formats totally open-ended, a specific format for these discussions that might be useful is “They say/I say”. There are bunch of they say/I say activities and resources on the web. Here’s one. https://www.csub.edu/eap-riap/theysay.pdf . You might ask students to do they say/I say with the reading/lecture as their original post, then they say/I say as they comment on their peers’ posts.

Another great activity is retrieval practice: students practice retrieving course ideas from memory without looking at their notes. (Psychologists tell us this helps us retain information; I do this in my face to face classes at the beginning or end of most class periods.) I can imagine lots of ways to turn this into a useful discussion forum. Ask each student to share two of their own retrieval practice ideas without looking at others’ posts. Or ask each student to share two ideas that haven’t been shared yet. Either way, you can then use this to see what’s standing out to them and what they’re missing. If no one mentions Important Idea X from the reading or lecture then maybe enter into the discussion and remind them of that idea with a new example or new explanation to help it stick. To make it more interactive, you could also require students to do a “yes and” comment on others’ posts: “Yes, that’s a great way to describe that idea. When I was processing that, it made me think of…”

If you run discussion forums, two things are essential. Break students into smallish groups (about 8 is ideal). Your learning management system should allow you to do this pretty automatically. And participate a lot early on, asking questions that students need to answer. Later in the semester, you can decrease your participation a bit. But sometimes these online discussion posts can feel for students like they’re shouting into the void. It’s important early on for students to know you’re listening and engaged.

This is a nice resource I just came across. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1gsukCtYIhe-PyofkdsIG6wUxytmkYg4XGIL9wIgoaSE/edit?fbclid=IwAR3u1owLlkPoErxIkRYfpTdXM-iHsUCSzrKPUYXJkZ-OxVzE8svtv7wa4Yw (Harry Brighouse shared this Gina!)

- What ground rules/class expectations would you recommend establishing or making explicit?

Yesterday I told my students: “we all need to start living on Titanium [our learning management system] and on email.” That was maybe an overstatement. But communication is one of the hardest things about online teaching. Usually, I begin my face to face classes – I’m sure you do this too – with business: what’s due when, what questions do students have, etc. We lose that online (asynchronously). So, it’s important that students know it’s their responsibility to check email or the LMS for announcements. Short of living on the LMS, maybe a reasonable expectation is that they’ll check course announcements/email once every day.

In that vein, I am promising my students that I won’t bombard them with emails/announcements. It’s really important to be thoughtful while crafting these communications. I don’t know how it is at Harvard, but we are getting a ton – too many – email updates about coronavirus and the state of the university. Things are constantly changing. We’re all on email overload. Students expressed frustration to me about this during our vent session. So, I recommend investing a lot of time upfront when communicating with students in an online setting. They’ll just stop reading the emails if they expect a revision is just around the corner. Or they’ll keep up and be stressed and confused and that will reduce their ability to learn. Either way, “measure twice, cut once” or whatever the saying is!

More on communication: establish when you’ll be available and how quickly you’ll respond. Will you always be at your computer on Tuesdays and Thursdays from 3-4pm, ready to answer emails or chat with students? Will you answer emails within 24 hours? Make crystal clear how they can initiate communication with you.

I am creating two general use discussion forums: student-to-student and student-to-professor. The former is a place for students to ask questions of each other. I told students I will not pay much attention to this. The latter is a place where they can ask questions of me. I told them I’ll check this regularly.

I also insisted that we all be flexible and forgiving. This is a major, weird, stressful transition for all of us. I explained the ways in which this is difficult for their teachers. So, I asked in advance for their flexibility and forgiveness. But I also said I would be both of those things with them. If they miss a deadline, for instance, they need to just honestly say so and ask for another opportunity. So much that’s new is being thrown at them and at us. No one should expect perfection or anything near that in this context.

Finally, I just wanted to remind them that their online persona is now their college persona. It’s easy for students to treat online classes like their other digital interactions with humans. But this isn’t that. They need to behave online, knowing that behavior is how they’re being seen and evaluated as college students. So, whatever that means for you clarify that. Does that mean they must always write grammatically? Tell them so. Does it mean no weird avatars? Okay. Yesterday, during a practice Zoom session with students, a student typed into the class chat “Give me 5 tokens and I’ll take something off.” I’m too old to really understand this, but it sounded like a joke about being paid to strip. He thought the chat was only between another student and him. But we all saw it. (He’s a good kid; we’ve got a laidback atmosphere. It was fine. But I said he shouldn’t do that again, and I used this as a cautionary example in all of my classes.) A general rule should be that they need to always act professionally in this context.

- Are there any online tools/platforms (e.g. Kialo) that you especially recommend?

I’m going to use Camtasia to create my lectures. It screen captures and records. That’s how I’ll deliver my end of the content. (I just learned it two days ago. It’s pretty user friendly.) Within my lectures, I’ll include some simple active learning techniques. At the end of a chunk of material, for example, I’ll give students an on-screen quiz in my slides and tell them to pause the video until they figure out the answer. Then play again to get the answer. Simple things like that.

My best recommendation is to familiarize yourself with your learning management system if you’re interested in going this extra distance. Watch online tutorials; google “creative active learning activities in Canvas” or whatever. These systems have a ton of features that mostly go unused. Familiarizing yourself with your learning management system may actually benefit you in your future face to face courses, whereas learning some other new technology may not.

- How do you conduct office hours when you teach online?

I’m telling students I’ll be at my computer at a certain time on certain days (similar to regular office hours). I’ll have an open Zoom meeting they can drop in on. I’ll check the student-to-professor forum and email at this time. I’m also giving my students my cell phone number. (I think this is totally optional; for members of groups who are often the targets of bias or harassment, it may not be a good idea.)

Sometimes I ask students to email me before my virtual office hours time answering two simple questions: Are you understanding the material? Do you think you’re going to make it through the class? It can be a simple Yes/No, or they can expand. (I’m pretty sure I stole this from one of my grad school colleagues, but I can’t remember whom. Probably Kristian Olsen, Heidi Furey, Luis Oliveira, or Jesse Fitts.) This is a chance for students to reach out to me directly and ask questions. The second one might be especially important given the weird situation we’re going through right now. FYI: I will not be doing this this semester, with nearly 150 students. I’ve done it when I was only teaching one class with 10-20 students. Also, I’m sure you know this, but you are not responsible or (probably) qualified to deal with students’ mental health concerns. If students share these concerns with you, bump them up the chain of command via appropriate protocols. (If you don’t know the appropriate measures to take in this kind of case, now is a good time to learn them.)

- How, if at all, do you adapt your assessment tools when you teach online?

Before I answer, one bit of advice I’ve seen floating around seems right and relevant to this question. The idea is something like: “You’re not now teaching an online class. You’re moving your face to face class online.” What this means to me is that the question at hand is not what’s the best way to assess student learning online. It’s more like: what’s the best (or maybe even just a good) way to assess student learning, given that half the semester was in person and that students enrolled in this class with certain expectations and that now I have to assess it using online tools in the context of a worldwide pandemic? In these circumstances, even approximating the ideal doesn’t seem to me to be the goal because one major desideratum at this point is minimizing disruption to students’ understanding of the course. (This is even more important given the fact, which I annoyingly keep emphasizing, that communication in online settings is difficult.)

I’m a big believer in process over product, especially in lower level courses. I care less about what students output than I do about how students learn. So, I’m trying to think about how I can mimic the learning process in this new setting without changing too much on students. For instance, in face to face courses I have students do reading quiz pairs (I stole that idea from Gina) to get them to engage with the reading. Engaging with the reading was the goal, not the quizzes. But these quizzes can be complicated online. So, now I’m trying to think of ways to get students to engage with the readings in some other way more appropriate to online learning. In the past, I’ve asked students to write reading responses. How feasible this is depends on student numbers.

If it helps, here’s how I’m working through things at the moment. First, figure out whether some assignments simply don’t make sense anymore. I have an assignment that asks students to meet with an expert on campus from a discipline other than philosophy to uncover philosophy in that discipline. Well, no one is on campus anymore, I don’t want them to do it via email, and everyone is going to be Zoomed out in no time. So, easy: drop this assignment. Adding lots of new assignments to replace ones like this will complicate things too much, to my mind. So, it’s just gone. Next, figure out which assignments can stay the same. I already have students upload to the LMS papers that they’ve written without much front-end input from me. I might drop one of these to ease everyone’s burden. But these assignments can pretty much stay the same. Then think about each of my remaining assignments and ask what I wanted them to learn and see how I need to adjust or replace the assignment. Online learning is often more independent learning. So, I might replace assignments that involved more dependence on me or others with other assignments that don’t. That being said, I am still considering whether group presentations will work. Students often tell me they usually put these together digitally anyway (using google slides and snapchat). How will they deliver them? Maybe via Zoom. We’ll see!

Even though assignments that are graded automatically (e.g., multiple choice exams) are not ideal – they’re not what I use face to face and they’re not what I’ve used in previous online classes – I am looking for ways to automate grading. (Your LMS has resources to do some automatic grading.) This won’t work in all philosophy classes for all assignments. But it might work in some classes for some assignments. If you put in some thought – maybe a lot of thought – it can be done well. A colleague of mine, for instance, uses multiple choice exams for logic. Students do the work on their own paper, but then have to choose an answer. This obviously increases students’ chance of getting the answer right. But I think that’s okay, especially in our current situation.

Others have already said this, so I won’t dwell on it, but I don’t think this is a good time to worry seriously about preventing cheating. Again, process not product. If a student cheats on an exam or assignment, they missed out on a learning opportunity. Their loss. I already craft some of my assignments in a way that cheating is really hard to do. (E.g., I don’t usually assign prompts that would already be assigned elsewhere.) But I also just try to create assignments, like open book open note exams, where it just doesn’t matter whether they look at their notes. Many of them are going to look at their notes, whether you permit it or not. If you shut down their browser (some software can do this), the ones who really want to are going to tape notes to the wall behind their computer. The students who lose out are the ones – the good the few? – who follow your rule about no notes. Better to just create open note assignments.

Lastly, I’ve heard professors making everything due each week at the same time. I have mixed feelings about this. If you space things out throughout the week, students will learn more because they’ll be thinking about the course more often. But maybe everything due on the same day is the practical thing to do. Some of my students did say they prefer having the same weekly schedule, with things due at the same time each week. (I don’t know whether that meant everything due one day, or just no variation in scheduling across weeks.)

- And of course, we’d welcome any other advice you think might be useful, that you have the time to give! [Grads: Josh has already sent me some suggested readings and podcasts, which I’ll append to the bottom of this document.]

I don’t think I’ve emphasized this enough or at all, but I’d recommend doing your best when creating your online materials to make as much of it reusable as possible. I will be making different videos for contingent info and info I intend to use again in the future. Next week, for instance, I’ll give a lecture on Norcross’s “Puppies, Pigs, and People.” But I’ll also need to inform students about due dates, etc. So: two videos. And while I’m making the Norcross video, I’m not going to reference specific, contingent information about this semester or this time. Maybe I can use it next semester to flip the classroom, or for some other purpose. I don’t know. But to increase the potential return on my investment, I want as much of this content to be reusable.

Finally: Be forgiving, not just of your students, but of yourself. I was honest with my students that their education is probably taking a hit with this transition. I’m going to do my best to continue to give them a good education during this weird new phase. But it’s not going to meet my own standards. I am just trying to remind myself: it’s okay. You should too!

Good luck! Feel free to reach out if you have specific questions. No promises that I’ll respond quickly or have something helpful to say. But I’m happy to help.

Some links and references from Josh:

Small Teaching Online

This book is based off of James Lang’s Small Teaching book, but applies his ideas there to online. The idea behind “small teaching” is to look for small changes you can make to your teaching that are high impact. He tells the story of how he would give talks at universities in the middle of the semester about all the ways professors should overhaul and revolutionize their teaching. But, of course, they didn’t because it was the middle of the semester. So, his Small Teaching book identifies like 10 simple high impact strategies that teachers could employ tomorrow, or next week, into their teaching. Small Teaching Online is a book that applies that idea to online teaching. I haven’t read it yet. I had my eye on it, but it came out right after I would no longer be scheduled to do much online teaching. I just bought it. Your students might find some good tips in either of these books. Small teaching (in the sense I just described!) is, I think, exactly what we need right now.

Teaching in Higher Ed Podcast

This is in general a really good podcast about, well, teaching in higher ed. In each episode, the host, a professor herself, interviews another professor about a certain teaching issue. I’ve been inspired by many of these episodes. Most relevant right now: there are several episodes devoted to online teaching, including an interview with the author of Small Teaching Online. I’ll link to the online versions, but you can download episodes in your favorite “podcatcher.” Aren’t I cool for using that word?

Here’s the Small Teaching Online episode:Â https://teachinginhighered.com/podcast/small-teaching-online/

Here’s the main site:Â https://teachinginhighered.com/

{ 6 comments }

Brandon Watson 03.15.20 at 8:07 pm

This is a great post. I’d like to suggest, though, that instructors often have an ethical obligation to try to maintain at least some synchronous instructional interaction in this transition. There are lots of good reasons to go asynchronous in an online course; there are good reasons to make a significant part of the course asynchronous in order to give students more flexibility. But I think, with rare exceptions, the primary reason why students sign up for campus classes rather than online classes, when both are available, is precisely that the campus courses involve ongoing synchronous interaction with the instructor. (I think a more clear structure for scheduling is another, but there are ways to handle this in an asynchronous setting.)

Now, of course, there are lots of ways to do this — it’s not necessarily, as it seems to suggest in post, just video classroom at the ordinary class time. It could be, for instance, having brief once-a-week tutorial groups by chat or video, or extended online office hours where students are required to checked in occasionally to discuss the readings in order to get their course participation credit, or some such. And, of course, there might be courses where, for practical purposes, it won’t make enough of a difference to matter. But in many cases I think that maintaining at least some small and well defined synchronous instruction is essential for preserving what many students were there for in the first place. The online learning in this case doesn’t exist for its own sake; it’s a duct-tape make-do for the fact that something is preventing students from being on campus despite having signed up for an on-campus class.

Kevin M 03.15.20 at 9:10 pm

Thanks to both Josh and Gina — some great and helpful stuff in here. If either of you have a moment, I’d love to hear more about how reading quiz pairs work. The name makes it sounds like something that could be adapted fairly easily to an online environment, but Josh’s remarks suggest that that isn’t the case. Anyway — I’m curious to know more so that I can think about whether it might be. Thanks!

Gina 03.17.20 at 6:36 pm

Hi Kevin M,

The reading quiz pairs are meant to 1.) give students regular recall practice; 2.) be a quick and easy reading accountability mechanism; and 3.) help students practice finding the pieces of a reading that are crucial to its main argument. I haven’t done it recently for various reasons, but I used to do it for a class that met twice weekly. The reading was all done for the Tuesday, and they’d take a short, 4 question, multiple-choice quiz over the main argumentative moves of the article. They’d submit the quiz. Then on Thursday, they’d get the same quiz and take it again. So each week there are 8 quiz points available, and they can get questions right on the second try that the missed on the first. In between Tuesday and Thursday, they could go back to the reading or talk to their classmates or raise questions in lecture/discussion to try to better understand what they didn’t know the answer to when they took the quiz on the Tuesday. I suppose the online teaching version would involve imposing a time limit but making the quiz itself open-note, so the interval between the first time and the second could involve a more careful searching out than a student could do in real-time while taking the quiz. Let me know if you have other thoughts about adapting to online!

Gina 03.17.20 at 6:49 pm

Hi Brandon,

If I understood him correctly, it sounds like Josh *is* going to have synchronous office hours.

But I did want to suggest that, where there is such an obligation, it must be defeasible. First, while the real-time interaction with the instructor might be part of what they’re there for, it’s not the only valuable thing our courses can offer them. We can set them up for synchronous interaction *with each other*, and, structured right, and with the right buy-in elicited from them, that could be really valuable. Second, and more importantly, the obligation must be defeasible because so many of us are up against so much right now, including other demanding moral obligations that might ultimately be more important to fulfill than the obligation to give our students an online experience that as closely as possible approximates what they came for in the first place. (Note how weak that claim is: the subordinated obligation is a very specific one; not, for example, the obligation to *teach them well*.)

Or anyway, so it seems to me.

harry b 03.17.20 at 8:43 pm

For what it is worth, I am planning to hold synchronous office hours and ALSO synchronous NON-office hours. Our system allows us to create a session which anyone in the class can log into, and talk with anyone else who is there. I figure this might work with discussion sections but also with my smaller class full of eager students — some of whom are already desperate for synchronous interaction with people they don’t live with….

ph 03.18.20 at 2:57 am

Adjuncts do most of the teaching. My lighter class load will be 14 classes in the spring, working with three different tech teams minimum, on three different platforms, if we go online. Opinions have in some cases been solicited, in others not.

Of course, those doing most of the teaching are rarely, if ever, invited to help in the decision making process on any topic, so in that sense at least the changes look to be ‘seamless.’ Ahem.

Online learning is great in many ways, but not like this. Really.

Comments on this entry are closed.