Alright, I used to perpetrate some literary criticism around this place. [Slaps wall.] Seems like I could still. This is going to be very flimsy because I’m just banging it out, because I might want some of it later, more worked out.

Over at the dying bird, Jeet Heer asks a good question: “Has anyone written about the genre of the “hippy noir”? Altman’s Long Goodbye, Big Lebowski, Inherent Vice, The Nice Guys. Are there others? An interesting little niche.”

He got good responses. Me: Philip K. Dick, Scanner Darkly, not just because it fits the bill but because of Dick himself, writing those weird letters to the FBI. He was a sad, harassed hippy noir detective. He lived the nightmare. That’s gotta count. Once you’ve got Dick, you add in others like Jonathan Lethem, Gun, With Occasional Music.

I’ve got further thoughts about the likes of Lethem but, first, flip it. Just as hippy noir is often good, the reason G.K. Chesterton’s Father Brown stories are invariably bad is that they are ‘hippy puncher noir’, so to speak.

No, not hippies, too early for that. But still, it’s that: the repetitive trope is the innocent detective finds himself fallen among decadents who lack any moral compass and, furthermore, lack even any proper sense that they lack one. So far, so hippy noir.

So Brown does not just solve the murder, he punches these damn hippies, in smug, self-satisfied fashion. In hippy noir the righteous straight-arrow loses his way, awash in weirdness he can’t restore to normal because he can’t even see to that solid shore to swim for it. In hippy-puncher noir, the straight-arrow effortlessly exposes everyone who isn’t normal – normal is who he is – as a fool. Hippy puncher noir is reactionary Mary Sue of a sort.

But, interestingly, almost the same lazy formula works brilliantly and originally in Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday. It works because it punches through hippy noir to some hidden other side, strikes through the mask, rather than just complacently punching hippies. It doesn’t smugly re-affirm conservative, conventional mores against those of dissolute nihilists. From hanging out with the nihilists, trying to solve crime, our hero comes to see what is shallow and nonsensical, indeed, non-existent in his own world-view. So far, so much just the thing hippy noir inflicts on a straight-shooter. But, somehow, in Thursday, through it, we arrive … somewhere else?

Maybe that’s just the Higher Complacency. That’s the worry, with Chesterton. You get sheer complacency (Father Brown, Orthodoxy) or, if you are lucky, brilliant Higher Complacency (Thursday, Napoleon of Notting Hill, Manalive, lots of the essays). The latter is way better than Father Brown. (I always want to punch that guy.)

But we aren’t done. Hippy noir is a subset of a larger class of detective fiction – namely, works in which the strong premise of background ‘normality’ is denied. Rather than your classic ‘normal’, quiet English village, a rural Eden whose innocence the detective is to defend and restore, you have some thoroughly messed up background situation that engages the reader’s ‘sociological imagination’, a la C. Wright Mills. One might say: you can’t solve the crime, only unravel the fabric within which it is, secretly, normal. Many ‘standard’ detective novels play with this, variously. Eden was never Eden, and we can’t solve the crime, proper, until we admit it. This is basically plain old noir.

So: duh. Hippy noir is noir.

But seeing it this way, we see that dark comes in different shades. Noir is a rainbow of grey.

For example, society itself is not just not Eden, normally, but normally so basically incomprehensible – so ‘far from God’ that it is the reason the crime can’t be solved, or even conceived of as such. You get existentially-tinged detective fiction, e.g. The Third Man. Lots of examples of this. Straight noir is always on the verge of turning existential. The hard-boiled gumshoe has a bit of the Kierkegaardian Knight of Faith about him. Oddly ordinary, that is, but with ‘inner’ extra, making him immune to much.

Now add: the case is now near to the detective story-as-Kafkaesque. That makes intuitive sense. And so the question becomes: who first notices it? Who first sees Kafka stories – especially the novels, The Trial and The Castle, are structurally noir, with a twist? Not hippy noir, more specifically, but isomorphic insofar as the protagonist is trying to ‘solve it’ but can’t because ALL these people are so weird it’s impossible to take your bearings with them. There is not ‘it’, then, so no solving.

I think the first critic to write about this may be W.H. Auden, in “K’s Quest”, in The Kafka Problem (1946). (If anyone knows of earlier comparisons between Kafka’s novels and detective fiction, I would be curious to hear it.)

[Memo to self: write a long Lovecraft pastiche, ‘The Call of K’, which is basically The Trial, and another which is basically At The Mountains of Madness, but written so there is a land surveyor lost and stumbling on these ancient ruins. Have his assistants been possessed by some strange, alien force? They are acting curiously.]

Now: why did I happen to have Auden at my fingertips? Because I’ve been thinking about Kafka and the post-war reception of Kafka. And I had an idea but I didn’t have the receipts. Fortunately, this piece by Brian Goodman came out a few weeks ago and basically rolled the stone off my tongue. All this sounds about right, I would have guessed it: how Kafka came to seem like an ‘anti-totalitarian’ fiction writer.

But even if the Kafkaesque was an invention of the interwar literary Left, the term took on new anti-totalitarian political associations after the onset of the Cold War. The second usage of “Kafkaesque” in the OED, listed after Wilson’s description of Grosz’s nightmare, comes from the Hungarian British writer Arthur Koestler, a former Communist Party member who became a leading anti-Stalinist in the late forties.

Yes, if the ‘K’ points you to ‘Koestler’, this is going to seem like it makes total (anti-total!) sense.

I got interested in this because I was thinking about this David Foster Wallace essay about how American college students don’t find Kafka ‘funny’. His brand humor is lost on them. I generalised that in my mind too: oddly, people miss the sunny side to Kakfa. We figure anti-totalitarian allegory should be fearful, not with a core or base of cheerfulness. Yet that seems to be Kafka. You shouldn’t miss it. I soon discovered there’s a Twitter feed dedicated to it.

Part of the problem is that the fiction can seem like Kafka saying: this is BAD, indicting ‘the system’. But actually he seems too wrapped up in himself for that. It’s kind of the final stage of hippie noir, where you, oddly, lose track of the ‘noir’ itself. But ‘hippy’ doesn’t land, for Kafka. He’s not a hippy, or familiar with them. But if you just say ‘weird’ that works. He writes ‘weird noir’, and hippy noir is that. It gets just … funny-weird for funny’s sake. Thinking that Kafka is anti-totalitarian is sort of like thinking Edward Gorey is very bitter at the shallow inauthenticity of Victorian-Edwardian culture.

OK, this is running on a bit long. A few curious bits, to tie it off.

Goodman mentions in his piece that the first occurrence of ‘Kafka-esque’ comes in a 1938 Cecil Day Lewis piece in “New Masses”. I tracked it down. Here it is. His idea: middle-class communists in England are so far from the working class, in terms of their actual lived experience, that they are driven to somewhat fantastic extremes, to express their ideas about what’s wrong.

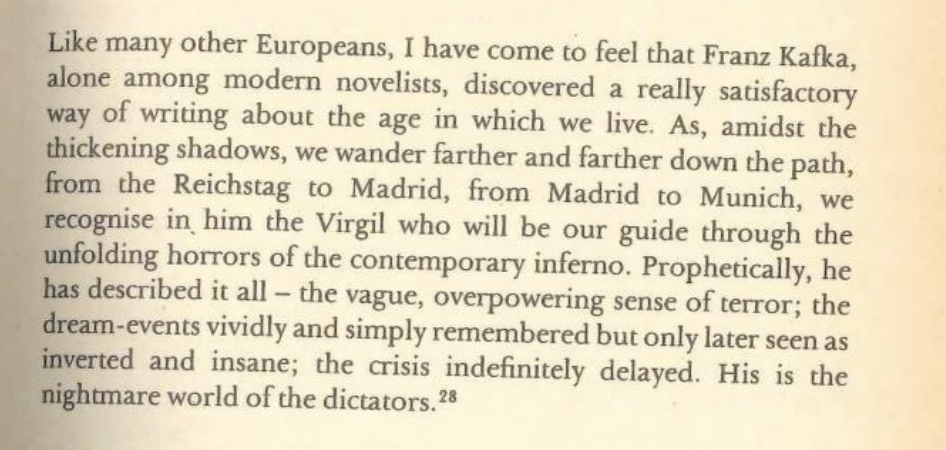

And one more. Here’s a bit from Christopher Isherwood, in “The New Republic”, from 1939:

The Virgil comparison is funny. You can imagine a version of Dante in which Virgil, because he can only go so far, see so far, is a more inadvertent guide. Instead of knowing where Dante is going, he’s just wandering around in some thoroughly pagan way, which happens to be on-track, Christianity-wise.

That’s enough for now. I haven’t really thought this through. But I’ve made some Kafka swag, if that appeals to you, sort of playing with how Kafka seems … oddly serene.

{ 28 comments }

Neville Morley 07.19.23 at 6:23 am

This is mostly far too clever for me, but it did immediately remind me of Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy, which I loved when I was about seventeen, which very self-consciously takes up the idea of Kafkaesque existential crisis explored through noir tropes.

DocAmazing 07.19.23 at 6:31 am

The most obvious of the Hippy Noir works would be the Mose Wine novels by that lovable right-wing zany Roger L. Simon, whose brain was so broken by the implications of his busted Eden that the last Moses Wine novel is some very strange stuff set in Israel and pushing the idea that Jews should never assimilate, followed by his becoming the fascist enabler he is today.

DavidtheK 07.19.23 at 12:12 pm

To have African-Americans and civil rights issues represented would Walter Mosley’s novels belong in this category?

Henry Farrell 07.19.23 at 3:20 pm

Borges’ “Death and the Compass” is certainly, and I think deliberately, Kafka noir. There is also – as I tried to exploit in my shoggoth piece – a separate and distinct thread via Jarrell’s take on Kafka to Lovecraftian visions of alienation (a la Borges, Lovecraft is a precursor – we need Kafka properly to understand him).

But you are very wrong on the Father Brown stories. There are too many of them, but there is a glorious strangeness to the best ones, which transcends his patness, and becomes a wellspring for Wolfe. “The Queer Feet,” for example, which is all about his conservatism (the classes should be distinct) but juxtaposes it with the radical weirdness of his version of Catholicism (that they can so easily blur into each other tells us that his world is not just Catholic but catholic). “The Sign of the Broken Sword” too. And there are others.

steven t johnson 07.19.23 at 4:54 pm

“…the innocent detective finds himself fallen among decadents who lack any moral compass and, furthermore, lack even any proper sense that they lack one. So far, so hippy noir.”

It seems I can never keep up. In hippy noir, are the decadents, the hippies? They’re the colorful amoral ones who populate the ostensible criminal plot.

Or is it the detectives? I thought hippies were supposed to be hairy, unkempt, disengaged and too stoned to really care. Any justicing the hippy detective does is more or less accidental.

Marlowe is to my eye about as appealing as Father Brown. Like Father Brown he punches the amoral decadents/hippies.

I’m so far from understanding the whole concept I’m wondering if Hammett’s The Thin Man isn’t an anticipation of hippy noir.

As for Kafka…I vaguely remember laughing (well, giggling) at The Metamorphosis, but I’m not sure I’ve ever read anything else by him in the fifty years since.

steven t johnson 07.19.23 at 5:12 pm

Never cared much for Father Brown stories, found it much easier to read Four Faultless Felons and Club of Queer Trades. And I discover The Man Who Knew Too Much is also cheaply available from Kindle.

There was a low budget adaptation of The Man Who Was Thursday written and directed by a Balazs Juszt, with Francois Arnaud as Thursday from 2016.

John Holbo 07.20.23 at 1:20 am

OK, maybe I need to read more Father Brown. I just found them very smug and one-note. But, since it’s Chesterton, he can’t have failed to write some really good ones in there!

J-D 07.20.23 at 3:42 am

I write not to make a case for the merits of the Father Brown stories–I’m sure people find many faults with them, and often justly. But this descriptions of them isn’t fair.

First, there’s nothing noir about them, because they are consistently underpinned by the implicit faith of the Catholic protagonist (and, presumably, the Catholic author) in the guaranteed ultimate triumph of good: Father Brown has nothing of the cynicism or ambivalence of noir.

It is true–I can think of more than one example, although it’s a serious exaggeration to suggest that there are examples in all or even most of the stories–that Father Brown sometimes encounters people whom he considers monstrously amoral. I imagine that if somebody had asked GK Chesterton explicitly ‘Can there be a human being who is utterly irredeemable?’, Catholic doctrine would have constrained the answer ‘No’, but more than once the Father Brown stories seem to portray (a few) characters as inhumanly irredeemable in their wickedness (although see the ending of ‘The Chief Mourner Of Marne’).

I don’t think, however, there is any of the stories in which Father Brown is surrounded (or nearly surrounded or mostly surrounded or temporarily surrounded) by characters like this. On the contrary, these characters are usually described in their inhuman amorality in order to contrast them with other characters in the story–often if not always the actual criminals. The criminals in the Father Brown stories (when they have them, because in some of them there’s no crime at all) are often (although not always) shown as having behaved in a natural and all-t00-human fashion, and are more often criticised by Father Brown for defects in their moral judgement than for a complete absence of one.

Also, the stories sometimes show up the people who differ from Father Brown as mere fools, but more commonly they are honestly mistaken, honest enough to be supposed capable of recognising their errors when Father Brown points them out.

John Holbo 07.20.23 at 4:44 am

You’re right, J-D, I amend it to ‘hippy-punching in the sun’. I’m sticking with hippy-punching because I think the schtick is that everyone’s compass turns out to be off besides Brown’s. And that’s the trope in hippy-noir. Everyone is nuts and it’s hard to solve a crime in the loony bin.

J-D 07.20.23 at 5:40 am

That might be a fair enough description of some of the stories (for example, ‘The Hammer Of God’ or ‘The Crime Of The Communist’) but not of others (for example, ‘The Honour Of Israel Gow’ or ‘The Point Of A Pin’). I’d be curious to know how many of the stories you would apply that description to after reviewing a list of them.

Adam Roberts 07.20.23 at 5:48 am

‘Hippy Detective’ makes me think of the Scooby Doo gang. That’s noir, in a way (neo-Gothic comedy is sort of noir). That’s also 1960s-70s, of course, so contemporaneous.

The Kafka stuff is fascinating. My sense, from Googling and JSTORing around some, is that ‘Kafka is Detective Fiction’ was quite widely discussed in the later 1940s, though I can’t find any specific examples that predate the Auden you quote. But for instance: Al Votaw’s ‘Kafka and Miss Blandish’ in ‘The Lit. of Extreme Situations’, Horizon, xix, 1949, 145-60, argues “that the typical form of literature between the World Wars 4 is a symbiotic union of the modern detective story with the novels of Kafka, and notes affinities between Kafka and the American literature of loneliness, violence and despair, both being reactions to similar absurd situations” [quoting W I Lucas’s summary of the piece] and there are a half-dozen other similar things from the same sort of time.

J. Eel 07.20.23 at 1:34 pm

I’ve just started Peter Gay’s Victoria to Freud series and something that strikes me is that Kafka and Freud are pretty similar figures in terms of the relationship between their work and how it was received by later generations. Gay really drives home how small, precarious, anxious, novel, and atypical the pre-war bourgeoisie was. Freud and Kafka were obviously quite different from one another, generationally for one thing, but also in how they processed and engaged with their situations, but both had idiosyncratic takes on their environments that were available because of the insight and contemplation their relative affluence and education gave them access to. But while their work was produced for an era in which their native class was an embattled minority, it happened to be the intellectual framework that was available to understand the genuinely middle-class mass society that emerged after the war, even though the meaning of “middle class” had changed utterly.

As an aside on the hippy noir Kafka totalitarian thing, I’d strongly recommend Stanislaw Lem’s Memoirs Found In A Bathtub, which is almost explicitly a comedic Cold War Kafkaesque noir farce and has some features in common with The Man Who Was Thursday (which I guess is an inevitable consequence of being what it is).

Brandon Watson 07.20.23 at 5:55 pm

The point of the Father Brown stories is very much what one would expect of Chesterton, that things are paradoxically not what they seem. This is practically underlined by the title of one of the collections, The Innocence of Father Brown, because one of the paradoxes of Father Brown is that he seems innocent in the way the post suggests, but he is in fact innocent in the opposite way — the reason that he can solve many of his cases is that he is vastly more familiar with evil and folly than, and therefore lacks the foolish naivete of, more worldly people, so that what seems shocking and monstrous to the rest of us, to him is often very human, very petty, and at times almost boringly predictable. This is explicitly highlighted in several stories, in the form that, despite as a Catholic curate being exactly the sort of person people would have taken to be unworldly and mired in superstitions, he completely lacks ‘superstitions’ about human nature (and occasionally other things) that worldly people have, and therefore can see how the events had to have actually unfolded. I suppose this could be seen as smug, but satires of supersititions often are seen that way, especially by the people who hold them.

engels 07.20.23 at 7:00 pm

“Keep calm and scurry on—Franz Kafka”

I thought it was TS Eliot (or maybe that was “scuttle on”).

burritoboy 07.20.23 at 7:59 pm

Beyond that Chesterton’s Father Brown is, as has already been pointed out, absolutely, resolutely not noir at all, but also: Chesterton’s “hippies” when they appear in Father Brown are usually surface spiritualists / Bohos / alternative lifestyles folks of the (largely) teens, twenties and thirties. We tend to view these types through the lenses of the superficially similar people of the late Sixties, or through the lenses of the beatniks. But these two groups were actually quite different, and were different in central ways: most of the people satirized in Father Brown are bored, lazy/indifferent, intentionally irresponsible rich or upper middle class and middle-aged people who have usually let their minds go to complete goo. (And the ones he satirizes the most are the grifty cult leaders who are manipulating their flocks, and the flocks usually get satirized more gently.) Chesterton doesn’t like the socialists either, but those are not usually what he is satirizing when he has these alternatives-lifestyles folks in Father Brown. A lot of these folks in the teens through the thirties either ended up being vaguely on the far Right, or being for extremely stupid forms of pacifism in the face of fascism, or just being so useless that they couldn’t manage to do anything at all.

engels 07.20.23 at 8:52 pm

This could actually be a line of literary merch: “Keep calm and marry up—Austen” etc.

AWOL 07.20.23 at 10:50 pm

Newt Thornburg’s “Cutter and Bone” is Hippie Noir. It also fits in Vietnam and Appalachia. It’s a brilliant work.

The “cult” movie based on it, “Cutter’s Way,” with Jeff Bridges and John Heard, changes the ending and distorts the message.

In the early 21st c. edition, don’t read the foreword. It’s written by a hippie-punching moron who never read the book.

MFB 07.21.23 at 8:58 am

Good stuff, this.

How about James Crumley’s novels, especially Dancing Bear?

AcademicLurker 07.21.23 at 6:44 pm

Does Robert Stone’s Dog Soldiers count? It involves the intersection of the criminal underworld and the 60s counterculture, but it’s not a detective story.

steven t johnson 07.21.23 at 7:00 pm

Still wondering if the hippy is the detective or the zoo of suspects is the psychedlia?

If the first, another early movie example is Robert Benton’s The Late Show, starring Art Carney and Lily Tomlin.

LFC 07.22.23 at 5:01 am

engels @ 14

I haven’t really followed the post and thread, but wouldn’t want you to think that your reference to “Prufrock” went unappreciated.

AWOL 07.22.23 at 1:11 pm

MFB:

“Dancing Bear” was the first Milo novel, right? It’s been so long.

Crumley’s a haze of booze. Wouldn’t you say he invented “Outsider Noir?”—introducing gay, Black, and unathletic offbeat characters into the mix of solving crime? Ironically, he started off fairly conservative with his Schraderesque “The last Good Kiss.”

JD 07.24.23 at 2:36 am

I thought it was called “stoner noir,” not hippie noir? Seems like the same thing, anyway. A lot has been written about it since the Inherent Vice movie came out.

The Higher Complacency is an absolutely marvelous label for what makes Chesterton Chesterton.

TM 07.24.23 at 7:24 am

I agree with 15: I don’t remember having encountered any hippies in Father Brown stories. I think it’s an abuse of terminology. “spiritualists / Bohos / alternative lifestyles folks of the (largely) teens, twenties and thirties”, yes, and often cynical and nihilistic, which is really not what defines actual hippies.

steven t johnson 07.24.23 at 3:15 pm

Sticking to movies, perhaps the Charlie Hunnam movie Last Looks (the title is a film stage reference) counts. His character is definitely more a make love, not war type, probably a deliberately casting against type of the star of Green Street Hooligans (and Sons of Anarchy?) And the newly reformed protagonist of Bullet Train, played by Brad Pitt, is yet another.

PatinIowa 07.25.23 at 12:39 am

I could make the case that there’s a touch of hippie/stoner noir in all of Pynchon from V until now. Remember the Zig-Zags and the hash in Gravity’s Rainbow? Of course, in Pynchon the underlying corruption seems to be capitalism/colonialism, or perhaps hierarchy itself.

Mostly though, I want to reread Red Harvest, where the outsider detective discovers that underneath an apparent snake pit of corrupt competing criminality is … wait for it … a real snake pit of corrupt competing criminality, and the best course of action is to amp up its violent compulsions until it destroys itself.

jack morava 07.25.23 at 12:46 pm

shout-out re Hammett’s Red Harvest, see also perhaps the Coen’s `Miller’s Crossing’?

KT2 07.26.23 at 10:34 pm

John Holbo: “… he punches these damn hippies, in smug, self-satisfied fashion”.

Perhaps Father Brown consulted:

“A History of California, Capitalism, and the World.”

…

“Remnants of a hippie counterculture have synthesized with high technology and big finance to produce the spiritually and materially ambitious heart of Silicon Valley, whose products are changing how we do everything from driving around to eating food. It is also a haunted toxic waste dump built on stolen Indian burial grounds, and an integral part of the capitalist world system.”

…

“that ends with a clear-eyed, radical proposition for how we might begin to change course.”

“Malcolm Harris, author of the new book Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World.”

https://www.environmentandsociety.org/mml/interview-malcolm-harris-author-palo-alto-history-california-capitalism-and-world

I haven’t read the book.

Yet it is surely an American / Silicon Valley script outline with back story ‘factual’ documentary, leading to prequels galore. Will Malcolm Harris’ book be optioned? (Opps. Writers strike). What would Chesterton & Kafka say?

Comments on this entry are closed.