The text telling me Tim had died came through a few minutes before a series of meetings with students. After the feeling of sickness and dread that hit me I wondered whether to go ahead anyway, and then thought what a strange thought that was. But my stepmum told me later that when my dad learned of my grandmother’s death he proceeded with the talk he was about to give to a group of teachers. I am pretty certain that if I’d been about to teach a class I would have gone ahead with that. But knowing neither meeting was urgent, and worrying that the students would be horrified to learn, later, that I had met them in such circumstances, I postponed. And to be fair, whereas he knew he could drive to where my grandmother was straight after the talk, I knew that I had to decide very quickly, and get ready, if I was going to leave that day, or have to wait another 24 hours (which, in the end, I elected to do anyway).

(Note: this is very long and probably self-indulgent. But I know plenty of non-regulars will want to read it, and I think writing it has helped me some. There’s a lot below the fold. That’s sort of an apology, but of course you can just ignore it!)

Visits never felt frequent enough or long enough.[1] But one upside of the pandemic was that my daughter, who was then living in England, forced him to learn how to use zoom (He then used zoom to interview people for his last, and most important, book, about which more another time). This meant we could talk from afar, but also allowed us to watch cricket together: two days before his surgery (after which he lasted just 10 days) we spent nearly two hours watching the end of a thriller that we were both willing the West Indies to win. When the estimated chance for WI to win was under 5% I suggested we put a hundred quid on it, but of course we didn’t, and of course WI did win, rather marvelously.

Tim devoted his life to education and, particularly, to schools. When I was a teenager he told me that teachers had the most important job there was. I asserted that doctors must be more important, because they saved lives, and dad said, no, there was something more important than saving lives. Teachers transform lives and make them worth living. In adulthood when I met teachers or people involved in education, once they knew my name they’d almost always ask if I was related to him. When they learned I was, the reaction varied from “I love your dad/Tim”, or “He does so much for the profession” to, quite frequently, some story about what he had done for the person I was talking to, or one of their parents or one or more of their children. Which, in turn, ranged from one of his tens of thousands of illegible handwritten notes (more than one of which I have seen framed in people’s living rooms), to much more specific stories in which he helped them out of a jam or gave them a unique opportunity, or gave them the confidence to apply to university, which changed their life. I was moved by Phillip Pullman’s tweet about how much he owed to my dad (Pullman started out as a middle school teacher in Oxfordshire; Tim suggested a scheme to him which paid him for a year to write full time – he never went back to the classroom). I remember, many years ago, sitting next to a successful academic talked glowingly of Tim, saying that she had been in a dead-end job, exploited by her boss, when my dad turned up and found a way out for her into a different job in which she was able to thrive and that led to her current situation.

The outpouring on social media, and in personal emails, has been startling to be honest.[2] They’ve come from hundreds of people who I don’t know, but who write, again, specifically about things that he did for them, or in some cases about how he influenced them even though they never met him. I’ve received emails from former cabinet ministers, journalists, heads, retired and non-retired classroom teachers, childhood friends of mine, even a woman around my age with whose family we would go on holiday in the late 1960s, and with whom he kept up and supported (we’d have been 6, and I remember as both utterly delightful and quite intimidating – but I was a very timid child so I’m sure she was actually merely delightful). It has been consoling in one way, but my childhood friend who is now a semi-retired vicar (and so knows the terrain) pointed out that I have been a sort of PR person for him, which alienates oneself from one’s own feelings. So, maybe not wholly healthy.

My brother, more savvy than I, observed that trawling through them the only actually negative tweet was from a conspiracy theorist who, anyway, only seemed to be saying that dad had been on the committee of some organization that Prince Andrew was sponsoring. (My stepmother told us that he only attended two meetings, anyway, for various reasons of which the nutter in question would approve, but also because after one of them he got completely lost in Buckingham Palace and had to be shown out by Prince Philip, an experience he didn’t want to repeat (the being lost, not the being salvaged by Prince Philip, which was fine)).

Another of the many emails I’ve received is from a woman who holds an academic chair at a Russell Group university, telling me that she work shadowed him before doing her A-Levels, and encouraged her to stay in touch, then to apply to Cambridge (where she went), then to pursue an academic career. A first generation college kid from an Asian-British family, attending a comprehensive school from which few went to college, and none to Oxbridge, she attributes those first steps to his influence. I forgot to tell her when I responded that I remembered him talking about her when she was shadowing him and later telling me he attended her wedding.

Tim is often portrayed as left wing old Labour. And yes, I suppose he was a left wing social-democrat or socialist of sorts. But it’s not that simple. In his early thirties he was approached by the Conservative Party to stand as an MP, and in his early forties was happy to vote for the SDP/Lib alliance. To the world he seemed to get more left wing as he aged, but I think what really was happening was that the landscape was shifting right (very quickly), and he just didn’t move right with it. At all. He represented the left wing of the post-war consensus and, while he recognized that was over, and was never tempted by the golden ageism that afflicted some of his near contemporaries, he held to the basic values, and looked to advance them, guerrilla fashion, in a less than full cooperative environment.

He was instinctively non-tribal. Most (perhaps all?) of his time as CEO in Oxfordshire the Tories were in charge. All the Tory MPs in county wrote him fulsome letters of praise when he moved on.[3] Later, although a skeptic about academies, he believed that it was vital to try and make your local school succeed whether it was an academy or not, and worked closely with several Academy Trusts. He never shared the disdain some on the traditional left have for faith schools, seeing them not as a necessary evil, but as a potentially and often actually valuable contribution to the overall system. And he was really disgusted that the secular left’s animus took hold only when, suddenly, Muslim state schools came on the scene. He liked and worked well with Lord Blunkett, and Andrew Adonis, with whom he worked closely in London, and was very fond of David Miliband, with whom he spent a lot of time when David was a young man. He admired some Tory Secretaries of State: particularly Gillian Shephard (with whom he had a lot in common). When Shephard took over as Secretary of State she asked for a lengthy meeting with him. He asked her why on earth she wanted to talk to him, and she said “Because everyone on my side is telling me I must never talk to you”. He made his own judgements, and was extremely pragmatic, if principled. He viscerally understood the import of Marx’s observation that human beings make history, but not in circumstances of their own choosing. I think I basically learned what non-ideal theory is, and how to do it, from him.

He said that his interest in school improvement began in childhood. He grew up first in Quorn and started at a grammar school which he hated so much that every morning he would feel physically sick, and would frequently convince his parents to keep him home. Sometime in that year they all moved to Lowestoft (my grandfather, who grew up in Ormskirk, had lost his job, and loved the sea), so my dad had to start at another school (Lowestoft County Grammar), this time, terrifyingly, in mid-year. His parents told him that at morning playtime he should find his older brother who would look after him in the playground. In his form room, where the teacher told him, kindly, that he should go up to the teacher at the beginning of every class and say “I’m the new boy, Brighouse”. So, in his second or third class, he did this, and the teacher at the desk, with great amusement, said “Yes, I know that, Brighouse, I’m your form teacher, and I just told you to go up to you teachers and introduce yourself”. By morning playtime he went up to his brother and said “You don’t need to look after me. I like it here”. And, indeed, he loved school from then on. He wondered how two schools could be so wildly different, despite having the same structure, roughly the same resources, the same assessments, etc. He spent most of his life puzzling about this and trying to make sure that children ended up having the kind of experience he did in his second, rather than the kind of experience he had in his first school.

(Tim was just 3 years older than Roger Waters, and if you’ve listened to Another Brick in the Wall you should know that that song, though good, isn’t imaginative. It captures what a lot of schools were like, for a lot of kids, in the post war years. Even, I think, for a good number of kids in my, post-Plowden, generation (though not for me). Tim had no interest in music at all, but when that song was a hit he would sing it round the house. It portrayed a way of doing things that he had set himself against. [Actually, although I say that he had no interest in music – he did enjoy chanting novelty songs, like Lily the Pink, or Thank You Very Much for the Aintree Iron, and the kid who lived across the road from us from 1970-75 messaged reminding me that on the occasions he drove us to school he would make us sing a song that went “Traffic Jam, Raspberry Jam, Strawberry Jam and Honey, We don’t care, we’ll be there, because we’ve got no money”. If you’ve read this far you might not be surprised to learn that, like King Charles, he knew the Ying Tong Song by heart]).

Tim was well-known around the time of the 1988 Reform Act as a vocal opponent of the National Curriculum – and, indeed, of the Tory move to centralize power over schooling. I was instinctively in favour of the NC, so argued with him about it at the time. He said this: “Look, if it were something that would fit on the back of an envelope, that would be fine – an improvement. But once you create it, it will take on a life of its own and become hundreds of pages long, and excessively prescriptive at a ridiculous level of detail”. If you’re familiar with Mrs Thatcher’s memoirs you’ll know that the National Curriculum was one of her regrets, because what she had envisaged was something that would fit on the back of an envelope, and she was dismayed when it became hundreds of pages long and excessively prescriptive at a ridiculous level of detail. When he interviewed Lord Baker, the Secretary of State for Education at the time, for his recent book (more on that in the post I promised earlier), Baker said that he regretted the centralization, and realizes it was a mistake, and that Tim was right. Tim’s delight in that had nothing to do with being right, but at the revelation of the decency and generosity of the man he’d fought with.

What he was really well-known for, though, was spending time in schools. He loved schools, and probably visited more than almost anyone who has ever lived. Wherever we went together in England he would point out a school (or sometimes point in the direction of some village) and have a story to tell about it – when it went comprehensive and why that was a smooth, or difficult, process; a primary head who had insisted on multi-age classes for 30 years, which had worked brilliantly because the head had managed to find staff who were utterly committed to this eccentricity; some architectural peculiarity that the governors had insisted on; a rural primary school where they decided to teach all the children three languages; a head compared with whose obsession with cricket dad’s and my own seemed pathetically amateurish. Etc.

He loved teachers, and thinking about teaching. I’ve not met anyone who combined such a responsible interest in research with deep and serious understanding of and fascination with practice. He didn’t tell people what to do in the classroom: he observed to people what seemed to be working for them, and suggested strategies he’d seen working elsewhere. He thought that everyone could improve, and one way you improved was by looking for strategies that had worked elsewhere and that you could realistically adapt for your own circumstances. He understood how people actually learn to do things well, in other words. And he understood how data could support good decision-making. Under his leadership Oxfordshire was the first LEA to require publication of exam results, not so that schools could be ranked, but so that people could compare schools with similar demographics, and see where to look for effective practices. IN Birmingham he insisted on disaggregating school level achievement data along demographic lines: if a school was doing well on average, but not with Afro-Caribbean students, or with Muslim girls, it needed to know that, and get support figuring out how to improve with the students it wasn’t doing well by.

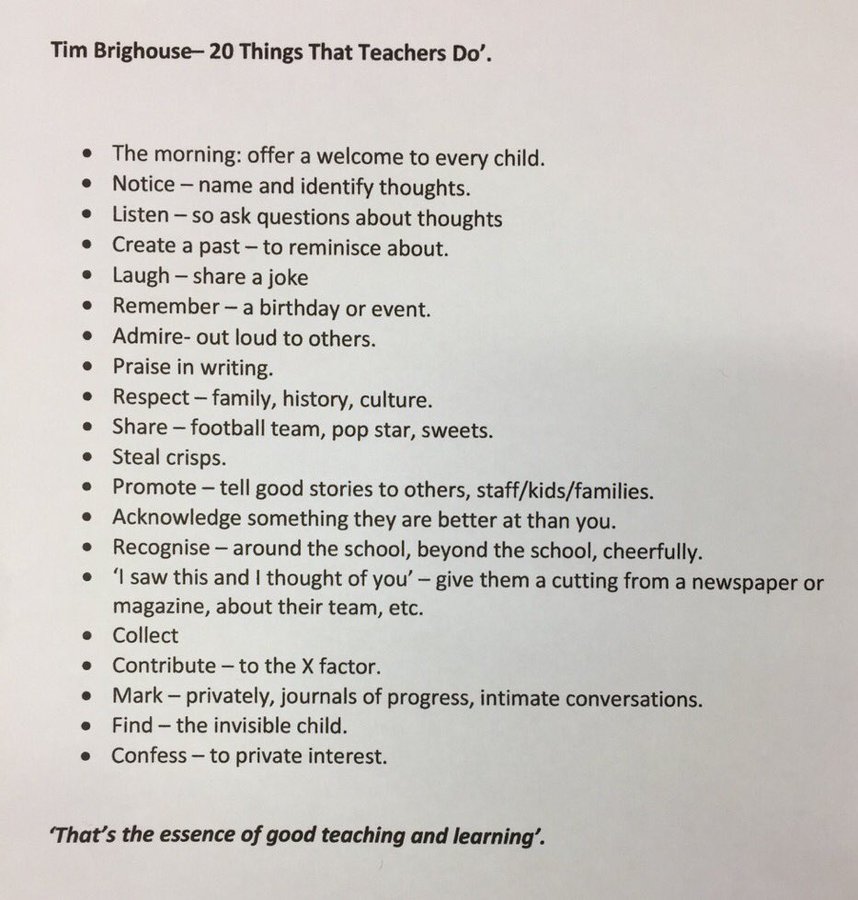

Here’s a picture which has been widely shared of “20 things teachers do”.

A couple of former students posted in on their instagrams; a couple more texted saying that they’d seen it and were amazed how many of those things I do. When I said “yeah but I don’t steal crisps” to one of them, herself an outstanding elementary school teacher, she replied: “No instead of stealing crisps you provide fizzy drinks and English chocolates to your students! And let them cry to you in your office about all their problems”. I had lunch on New Years Eve with two former students who now teach middle school (in Milwaukee and in Oakland), one of whom is making up a Canva version of “the 20 things teachers do” for her classroom. [We were alike in many ways, more so as we aged I think. You should see our offices! And of course teaching has been at the center of both our professional lives. Perhaps the most poignant thing someone has said was a friend (former student) who said “I’ve been reading lots about your dad, and I’ve really enjoyed reading about him, but sometimes it’s felt like I’m reading about you”.]

I don’t know whether he didn’t turn up at the office in Birmingham until two weeks after his job began, and, when asked where he’d been, said “visiting schools”. It is the kind of thing he would do. But the story about a school secretary – or caretaker – sending for the police because she feared a dodgy character was trying to enter the building is true. He was scruffy, and had wild, unkempt, hair (the grauniad obit called him “somewhat disheveled”, which suggests a level of typographic imperfection unusual even for the gaurnadi: unless “somewhat” is obituary code for “extremely”).[4] At a school event when I was in the 6th form a good but grizzled teacher once said to me, admiringly, “The thing about your dad is that when he walks into a room he seems to think he could be the caretaker. Except that he actually knows how important the caretaker is. Not like some people” (he indicated someone in the room who definitely didn’t behave like that).

He was always on the lookout for new ideas. In 1987 he accompanied me to a meeting of a very left wing organisation in LA, which we were driven to in the open back of a truck, all the way down Vermont Avenue. He was tickled that a quasi-Trotskyist group met in the basement (not the vault) or a bank, and quickly identified the voice of reason in a discussion about whether we should take over the operation of an alternative bookshop (the voice of reason was a veteran of both the SWP (expelled) and the Vietnam War). But what he really took away from the meeting was the idea of having every item on the agenda timed, something he said he had never seen before, and promised to adopt immediately for all the meetings he ran.

We weren’t always in agreement. At 17 I applied to Cambridge University, under considerable pressure from my parents and my school. I assumed I wouldn’t get in, so was a bit shocked when I did. He absolutely thought I should go, and was very disappointed that I didn’t. I’m not sure I could have articulated my actual reasons – I’m not sure I know them even now – but they weren’t grounded in a deep anti-elitism, because I knew even then that if we’d lived far enough away from Oxford (rather than in Oxford) I’d have been happy to go there. And anyway it’s not as though I didn’t go to university at all: I went to Bedford College, London, a perfectly respectable institution (though, admittedly, one that closed down at the end of my second year). He thought it was a serious mistake, and I understand better now why he thought that, especially given how central being an Oxford graduate was to the start in his own career. Without the connections or the accent that being properly middle class or going to a posh school would have given him, a second from Oxford was essential for the first job as a department head in a girl’s grammar school, which in turn was essential for subsequent opportunities. But he implied an apology when I graduated – academically (though probably not in other ways) I had couldn’t have made a better choice, which he acknowledged admiringly. Then, much later, when I was seeking his advice about job offers from Stanford and Penn, he told me that a mate of his had said “You can’t turn down Stanford”, to which Tim, reflecting on my 17 year old self, replied “Oh, I think Harry might be able to”, with a pride in his voice remembering which makes me cry as I write this.

Talking of crying, he had a quality till very late in life – maybe to the end – which I, and one of my daughters, share: the inability, when triggered correctly, to control his mirth. (With my daughter, in her pre-teen and early teen years, sometimes everyone in the room would lose control, often without knowing what she was laughing about). He would sometimes weep with laughter, knowing which, and knowing that I could do, made some interactions quite difficult. In 2019 we attended a Middlesex vs Gloucestershire County Championship tie at Merchant Taylors School (good grief that place is posh – more cricket fields than Eton!) with my son and our mate Bob. We sat very close to a man in a deckchair, who didn’t even have a Playfair annual, but kept contextualizing the events in a loud E.L. Whisty voice. When Murtagh took his third wicket the EL Whisty man invoked a match from 1953 in which the first three wickets had fallen to the same kind of dismissals in the same order to a right-arm seamer, and started calculating (in his head, accurately as far as I could gauge) the effects of the latest over on players’ season averages. He then compared the averages of players in the match to long dead players that even my dad, Bob, and I had never heard of (this was Middlesex, if we’d been in Lancashire or Gloucestershire than between us we’d have known them all). He just kept going with an astonishing depth of detail, all the time talking to no-one in particular. I realized at some point that if I looked at dad for more than a couple of seconds I’d lose control, which seemed unkind because it is magnificent that people like that exist and that cricket provides them with an outlet for their peculiarities, and enrich the lives of the rest of us who love the county game. But I couldn’t resist: I tried to say something about a different topic to dad which triggered both of us to start crying with laughter til it hurt, and for months afterward we would dissolve when remembering this lovely chap to each other.

Sometimes we found out that we’d come to like the same things, independently. He loved Rob Brydon, as I do, and actually lost it when I simply told him about the time Rob Brydon hosted the whole of the Ken Bruce show pretending to be Ken Bruce. He started telling me about this Yorkshire poet he listened to on the radio a lot – it was Ian McMillan, of whom I was already a fan (and that’s despite being entirely ignorant of his role in the marvelous The Blackburn Files!). After I’d been reading Paul Edwards’s cricket reports for about a year I told Tim he’d love them – in fact he was just about to tell me to read them. We both unknowingly bought Paul’s recent book for each other as a gift. (We recently unknowingly watched Paul umpire a game our friend Swift was playing in, and subsequently through twitter he invited me to meet up at some match this coming summer; Tim was thrilled, and looking forward to that as much as I was. If you read this, Paul, I’d still like to take you up on it, and hope you’ll join me in a drink to the old man). It was a not infrequent pleasure to discover that we were reading the same book at the same time. When he died he was 1/3rd of the way through David Kynaston’s Austerity Britain and I was half way through Kynaston’s Modernity Britain – Tim had discovered Kynaston through the latter volume, and I had sent him back to read Austerity Britain and Family Britain, which I read a while ago, while I moved on to Modernity Britain.

He was wily. In 2001 we were at a meeting together in London with various trade union leaders, academics, DfE officials and, eventually, David Blunkett. A massive storm was blowing outside, so people had hung their jackets up on various pegs round the room. After a while a phone started ringing in one of the jackets, After 8 rings it stopped and then, a minute later, rang again. This went on for maybe 15 minutes (and nobody commented on it). We were both going back to Oxford, so once we were settled on the old X90, I asked him “Why didn’t you go and turn off your phone?”. “Because if I did, then everyone would know it was mine”. I’ve written before about the (wily) way that he got Oxfordshire’s schools to end corporal punishment.(He pointedly sent me to the school with the most difficult population and (unfairly) the worst reputation in the county, Peers, which had not used corporal punishment since its founding). The scheme that gave Philip Pullman, then a middle school teacher, a sabbatical (which Tim suggested to him) was a central government scheme supporting sabbaticals which only Tim and his mate who was CEO in Somerset knew about – so Somerset and Oxfordshire teachers got a lot of sabbaticals in the 3-4 years before someone at the DES figured out what was going on and closed down the scheme.

Equally wily but less successfully so: in 1977 he took me and my sister to see Monty Python and the Holy Grail at the Maidenhead Odeon, asking for “2 adults and one child”. On being told children weren’t allowed to see the film (incredible, really), he instantly said “in that case I’d like 3 adults please”. Charming as he was, we didn’t get in.

He was a good judge of people. He refused to believe the statistic that 1/3 of public school principals in the US were former gym teachers and athletic coaches, knowing that I might be making it up. It’s true (or was true then) but ridiculous. Having convinced him, I observed that the PE teacher at my school, Lynn Evans, would have been a great head, at which point he clutched his head in anguish and said “Shit, you’re right, why didn’t I make him a head!” (I was right, but as you can probably tell if you follow the link there’s no way Lynn Evans would have agreed to it, so I don’t actually think an opportunity was lost). But he didn’t always get people right. That school was a recent merger of a Grammar and Secondary Mod that had occupied contiguous sites. He recognized the deputy head, Bill Lewis, as a highly efficient and well-regarded administrator, who was key to maintaining morale during the merger, but had the impression that Lewis, who came from the Grammar, was unenthusiastic about the change. In fact Lewis was as committed to comprehensive education as dad was: and a discreet socialist, who was instrumental in my recruitment to left wing political activism. Tim was stunned when he recently learned that.

My parents were young when I was born, really of a different generation to many of my peers’ parents. And my dad always liked kids (which is a bloody good thing – I’m sixty and my dad has lived with and had a roughly parent-child relationship with at least one school age child almost continuously since I was born). He enjoyed children of all ages: even, incomprehensibly, adolescents. He bonded well with my friends. One, in particular, who had a difficult family situation, has told me in adulthood that my dad was a role model of how to be a man, that he really needed. My oldest friend of all (since 1970), whom I just saw for the first time in 38 years, recalled him with great enjoyment and affection. Another, whom I last saw in 1980 when she was 15, sent her condolences telling me that he was always charming to her, and recognized and chatted with her decades later at some posh function they both attended. His 9 grandchildren all gravitated to him; although startlingly different from one another in personality and interests, he was able to relate to each of them delightedly and delightfully, each on their own terms.

In recent years a lot of my best memories of him involve cricket. Unlike me he loved many sports, but, fortunately, cricket was his favorite. Here are a couple. Well, a couple more, you’ve already had two.

I planned my trip with my (then 12-year old) son to England in 2019 so that our last day would be the day of the World Cup final. I thought, presciently, that it was the one time in my dad’s life (and possibly in mine) that England might win, and I wanted to watch it (on telly) with the two of them. In the final 20 minutes or so I sat with my dad, tense as could be, on one side, and my son on the floor writhing with excitement and suspense. They each left the room on two separate occasions, because they couldn’t stand to watch, both of them unusually silent. In the very final moment of the superover, though, suddenly the room erupted, with both my dad and my son shouting “No, No, No…” as the ball was thrown to Buttler and “YES, YES, YES” when he swept down the stumps. I surreptitiously recorded the whole thing, and it is a joy to see my lad shouting with excitement while my dad joins him off screen.

The other was in the summer of 2021. We attended a charity match for Barnardo’s at Wormsley. The crowd was around 1,000: about 20% Afro-Caribbean, about 75% British Asians, a handful of white people and a smattering of the great and the good (Gordon Greenidge is tiny!). The cricket was… well, it wasn’t very good (no disrespect to captains Peter Oborne and Chris Lewis, but on the evidence no-one on either team is going to play professionally again). And it always seemed on the verge of raining. But everywhere we went people wanted to talk to Tim. It was like being with a celebrity, and numerous British Asians with Birmingham accents told me one or another kindness he’d done them or support he’d given them, or how he’d kick-started their career, or about some problem he’d helped them solve. He wanted to leave early so he wouldn’t be late for his wedding anniversary dinner [5], but it took us 45 minutes to get through the crowd because people would not only stop to talk to him, but then make him go and talk to their parents, or wives, or husbands, or children. While he was running the gauntlet, I ended up talking at length two British Asian sisters in their twenties I’d never met before who talked about his influence on them since early childhood – he would meet their parents in their house for work related reasons, but would always take an interest in them, and encourage them to find and pursue their interests.

One last thing. Tim was well known for his love of quotations. Two in particular have been circulating the internet. One is often wrongly attributed to him: It’s actually Judith Warren Little’s excellent an illuminating comment that:

School improvement is most surely and thoroughly achieved when: Teachers engage in frequent, continuous and increasingly concrete and precise talk about teaching practice (as distinct from teacher characteristics and failings, the social lives of teachers, the foibles and failures of students and their families, and the unfortunate demands of society on the school). By such talk, teachers build up a shared language adequate to the complexity of teaching, capable of distinguishing one practice and its virtue from another.[6]

I’ll leave you with ther other, which a few people have quoted on twitter, and I’m sure will be read at the funeral, from George Bernard Shaw. I think he really did live this way.

I am of the opinion that my life belongs to the community, and as long as I live, it is my privilege to do for it whatever I can. I want to be thoroughly used up when I die, for the harder I work, the more I live. Life is no “brief candle” to me. It is a sort of splendid torch which I have got hold of for a moment, and I want to make it burn as brightly as possible before handing it on to future generations.

[1] I didn’t see him at all, for obvious reasons, between 2019 and 2021. It would have been longer but for Gina who, when travel restrictions were relaxed sometime late in summer 2021, told me to just go, right then, on the grounds that my parents were old, and we had no idea whether the restrictions would still be relaxed by the next time I could go. I wouldn’t have gone if she hadn’t pushed me and would never have made that time up: the Wormsley cricket story toward the end wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t gone. I’ll always be grateful to her for that. Mark you, many years ago I gave her similar advice, similarly forcefully, when she was dithering in exactly the way I tend to.

[2] The social media outpouring began when friends (a politician and a journalist) told us we needed to make an announcement because word was getting round and if we didn’t do something soon we’d be inundated with calls. So the journalist gave me the language for a tweet, which I dutifully posted, having no idea what the response would be.

[3] Yes, this did include John Patten, whose praise may not have entirely reflected what he felt, but honestly I think it probably did, which is what made sacrificing his career for his subsequent slander so pathetic. Fwiw I know at least two of the Oxfordshire Tory MP’s of the time were being entirely sincere in their praise, and I’ll name one of them, Tony Baldry, with whom he got along famously.

[4] Last summer I bought some running shoes for him, because I thought he’d walk more if he had comfortable shoes. He asked how much they cost, so I halved the actual price and he still looked a bit dismayed, saying “I don’t believe in spending money on clothes”. Words to live by; and he did. Many people who know me will read that and think that the apple doesn’t always fall far from the tree.

[5] I organized his wedding about 30 years previously and so knew that it wasn’t, actually, their anniversary, but decided not to bother telling them till they got home from their fancy dinner.

[6] To be fair, it took me a long time to find the actual source for this one when I wanted to use it myself, and when I did so Judith asked where it was from, so I think Tim has quite a bit of responsibility for it being so widely known.

{ 10 comments }

John T 01.10.24 at 4:38 pm

Condolences. When I was reading about your father I was very struck by the unparalleled number of remarks from people who wanted to recall how he had helped them or inspired them, not generically, but in a specific, memorable way. I’d never seen anything like it, even for much more famous names.

It was very inspiring, and made me reconsider how one could help people (and how many people one could help)

Chris Armstrong 01.10.24 at 5:05 pm

This is really lovely, Harry. For a father and a son to love each other, be proud of each other, and share these small joys, is a wonderful thing. It’s not something I experienced as a son. But as a father, it has enriched my life immeasurably. He sounds like a wonderful person. Thank you for sharing.

Russell Arben Fox 01.10.24 at 6:53 pm

Thanks so much for this, Harry. Your father, and his world (which, of course, in so many ways became and perhaps always was also your own, at least insofar as you have presented it to CT readers over the years), present to my mind a vision of integrity, of someone being–to borrow from the Shaw quote your finish with–wholly a part of the lives and the fates of all those they are in community with, and being blessed by such accordingly. It’s just damn inspiring, and little weepy too. God bless you and the whole Brighouse clan this day, and God bless Tim too, who I’m personally confident is in the best of places right now (a confidence that I hope, one way or another, you can feel as well).

Fiona Aubrey-Smith 01.10.24 at 7:41 pm

Thank you for writing this Harry – I can almost hear Tim’s voice talking about these things as I read your words. That laugh! Those pauses, followed by a thought or more often a question. Those words of encouragement. Those poignant observations. So much to learn from in every exchange.

There are few people who have the ability to imprint people’s hearts and minds in the way that Tim did. What a phenomenal legacy he leaves and what a privilege it has been to share part of that journey.

Donna 01.11.24 at 12:18 am

This was such a pleasure to read. To make such an impact on so many lives is extraordinary. To be concerned and caring on such a personal level for others, to take time to see individuals and their potential, in whatever area that may be, to encourage and support people in a way that has stayed with them throughout their lives. And to do it without ego. What an amazing legacy.

Thank you for sharing Harry. I hope you’re enjoying your memories and recalling the happy times with your dad. xxx

Alan White 01.11.24 at 6:21 am

Poignant and celebratory Harry. My sorrow for your loss, but at the same time I celebrate your burning torch of a life in his stead.

Matt 01.11.24 at 10:29 am

It’s a lovely rememberance, Harry. Thanks for posting it. I still think you should have taken the job at Penn, though.

Alex Wallace 01.11.24 at 2:17 pm

May he rest in peace.

Jennifer Morton 01.11.24 at 11:46 pm

Absolutely lovely and moving. I am so sorry for your loss Harry but really glad for this moment to remember your remarkable dad.

Robert Young 01.21.24 at 5:27 pm

Many thanks, Harry, for sharing this very personal, deeply felt and illuminating tribute to your dad. My contact with Tim has been linked to his involvement with the National Association for Primary Education, of which he became President and to which he has been very generous with his time. His was the articulate voice of enlightenment, inspirational in tone,. always celebratory of the teaching profession and with that rare capacity of mixing anecdote with the fruits of research to powerful effect. With a twinkle in his eye and a sympathetic unassuming demeanour, he was always a joy to be with!

Comments on this entry are closed.