In the 18 months since I quit Twitter, I can feel the atrophy of my vibe detector. I’m reading more than ever, on Substack and the FT, Discord and group chats — much of the same “content” I would’ve encountered on Twitter, in fact, but without the ever-present spiderweb of the social graph, the network of accounts, RTs and likes that lets me understand not only what someone thinks but what everyone else thinks about them thinking that.

So while I know that I’m missing the vibes, I cannot, of course, know which vibes I’m missing. Knowledge of vibes means never being surprised when someone says something: I know what kind of person they are, and I know what those kinds of people say. This is why Twitter users participate in The Discourse rather than in human-to-human dialogue: given the unknowability of another person, when we openly converse with them, we can always be surprised by what they say.

Although various Discourses now take place both on and between other platforms, the architecture of Twitter is ideal for textual Discourse and it seems to remain the hub.

The first time I was realized I was way off of the main vibe came from the response to Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation. My readers will know that I am extremely sympathetic to at least part of his argument, which I’ll split up as follows:

- Children spend a lot of time on social media on smartphones. The ones who do not now have peers who spend a lot of time on social media on smartphones.

- This does something.

- Depression and anxiety among children is increasing dramatically, around the world, at about the same time that they start using social media on smartphones.

- There are some studies that test the obvious causal hypothesis; the evidence tends to point in the expected direction.

- We should change the norms and expectations (and in some cases, laws) around if and how children use social media on smartphones.

At multiple conferences about social media, politics and communication I attended this spring, people discussing the effects of social media went out of their way to criticize Haidt — ostensibly for exaggerating the amount of evidence in point 4, but in fact in order to communicate the correct vibe. This is a difficult balancing act; obviously, social media companies are bad, and lord knows there are many, many ways in which some social media users are bad — but we simply don’t have scientific evidence to know whether social media causes this particular bad thing.

It is understandable that social scientists to focus on Point 4, on evaluating the balance of evidence. That’s what we’re trained to do. However, in this case, I agree with Ben Recht’s provocative piece—I don’t care what the studies say. We cannot do good science on this question. A scientific orientation to this question is simply a category mistake, for a number of reasons. Most important, to me, is the temporal validity problem. “Social media” is not one thing, to conceive of “social media” as a treatment in the language of causal inference is ontological nonsense. And in the time it takes to measure the effects of “social media” in order to decide what to do about it, “social media” has changed.

In a footnote, Recht has a similar reaction to what I describe at the beginning:

I poked around, and most of the commentary was hating on Jonathan Haidt. I get it. Haidt is a preachy tut-tutter. But the counter-evidence is terrible as expected. In this Nature editorial, for example, the author cites not only a bunch of random metaanalyses but also a bizarro study using FMRI to spot brain changes from screen time. When you are leaning on FMRI to make your case, you have lost the argument.

On Twitter, the question at issue is whether Jonathan Haidt has a good or bad vibe. This is simply not an important question. But it is the question that using Twitter answers.

Another statistician and psychology metascience blogger, Daniël Lakens, reports a similar read of the evidence on the podcast he co-hosts:

I once reviewed a paper discussing [whether social media has negative effects]…I don’t have a dog in the fight…But I was reviewing this on this topic and my main comment was just “people, why are you even fighting over these things that you’ve shown all of this is such a mess you’re so far removed from having high-quality data to even try to address these questions…go back, stop fighting, go back and try to collect some real data here. Conceptualize what you’re talking about, like you are so far removed from even trying to test this.”

If I might flatter myself by comparison to such illustrious company, that’s three metascientists approaching the evidence and saying that it is radically inconclusive. My position is that it is impossible to produce a conclusive answer to this question; I wonder if Ben and Daniël, or any of my esteemed readers, disagree — and if so, what would it take to produce a conclusive answer?

But for now, let’s toss out Point 4.

- Children spend a lot of time on social media on smartphones. The ones who do not now have peers who spend a lot of time on social media on smartphones.

- This does something.

- Depression and anxiety among children is increasing dramatically, around the world, at about the same time that they start using social media on smartphones.

There are some studies that test the obvious causal hypothesis; the evidence tends to point in the expected direction.- We should change the norms and expectations (and in some cases, laws) around if and how children use social media on smartphones.

Points 1 and 3 are indisputably true. Point 5 is a normative argument; tossing out Point 4, there’s no connection to empirical Points 1-3. As I have repeatedly argued, digital social science should start at Point 5 — unlike in natural science, the logical chain should be “What kind of society do we want? What kind of technology will help us move towards the society we want? What actions can we take to promote that technology?” If you’re interested in teaching a course on this topic, here’s a syllabus.

“Evidence-based policymaking” at the scale of responding to social media is simply the fantasy of policy without politics — in the cybernetic terminology of Dan Davies’ fantastic recent book about Stafford Beer, it is an “accountability sink.” Technocratic politicians love it: they don’t have to be leaders, merely followers of the evidence—if things turn out poorly, well, that’s just how science works, it never claims to be perfect, merely self-correcting. It certainly wasn’t my fault—what do you want me to do, ignore the evidence?

But I want to talk about Point 2. Does social media cause anything?

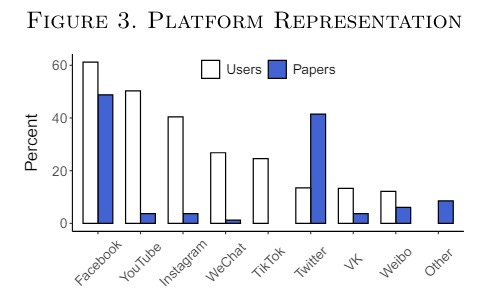

At a conference at Penn this spring, quantitative scholars of social media were ruing the fact that social media data is now generally harder to access, and how this would affect the research we can do. It’s true; we are coming off what I think will be seen as a golden era of social data accessibility. I’ve taught hundreds of students how to scrape Twitter data live in the classroom, thanks to the open API — a valuable exercise in helping students transcend the helplessness that many feel when dealing with coding for the first time.

On the other hand, we’ve gotten hooked on this cheap data. Following the “data imperative” so aptly described in Fourcade and Healy’s new book The Ordinal Society, too much computational social science begins from the data and says “What questions can we answer with this?”

This is a fundamentally academic approach, in the derogatory sense. Instead, we should be asking questions like “What is social media? What does it do?”

Because I’m pretty sure it does (causes) something!

Trivially, I think everything causes something, and everything is caused. Now, these “things” might not be the sorts of things that we have decided to highlight about the world. “Depression,” for example, is a thing that is constructed by the answers to a battery of questions for the purposes of the scientific studies under question. One of the biggest (or at least causally upstream) problems in contemporary behavioral/computational social science, in my opinion, is the lack of an ontology. This comes before causal inference or even quantitative description; before we can describe the extent to which things are, we need to know what things are.

As I wrote in How to Research New Media Effects, when we encounter these new media the world serves up, these new causes, we shouldn’t automatically be asking whether the effects of these new causes are the same as the old effects of the old causes. There’s simply no guarantees that old data or theories are relevant to the new world. We should instead think about what these new things are — and what they might cause.

I know quite a lot about YouTube; I wrote a book about what it is, replete with theorization about what it might cause. And I know intimately what Twitter was, have written perhaps too much about what I think it causes.

I know less about Facebook or Instagram; I haven’t used either in over a decade. But they’re clearly new things. And by this standard, the idea that they might cause a different effect than previous media caused — teenage depression — seems eminently reasonable.

Certainly, I think that misery causes Facebook — that Facebook is other people — so it’s not shocking that the output might be misery as well.

Social media has been around for a long time. It’s been intensely studied by academics for over a decade. If we can’t say whether social media causes teen depression, what can we say it causes?

I’m serious — I think this is an important part of the academic knowledge production process. We need to spend more time and raise the status of summarizing and synthesizing knowledge. This will help provide knowledge that citizens and policymakers can use, and will help us “set the academic agenda.”

The current procedure seems to be a disaster. “Famous, controversial academic summarizes a literature he’s only adjacent to in service of a bestselling book with normative conclusions” produces mainly ad hoc ad hominem vibe analysis, rather than rigorous synthesis.

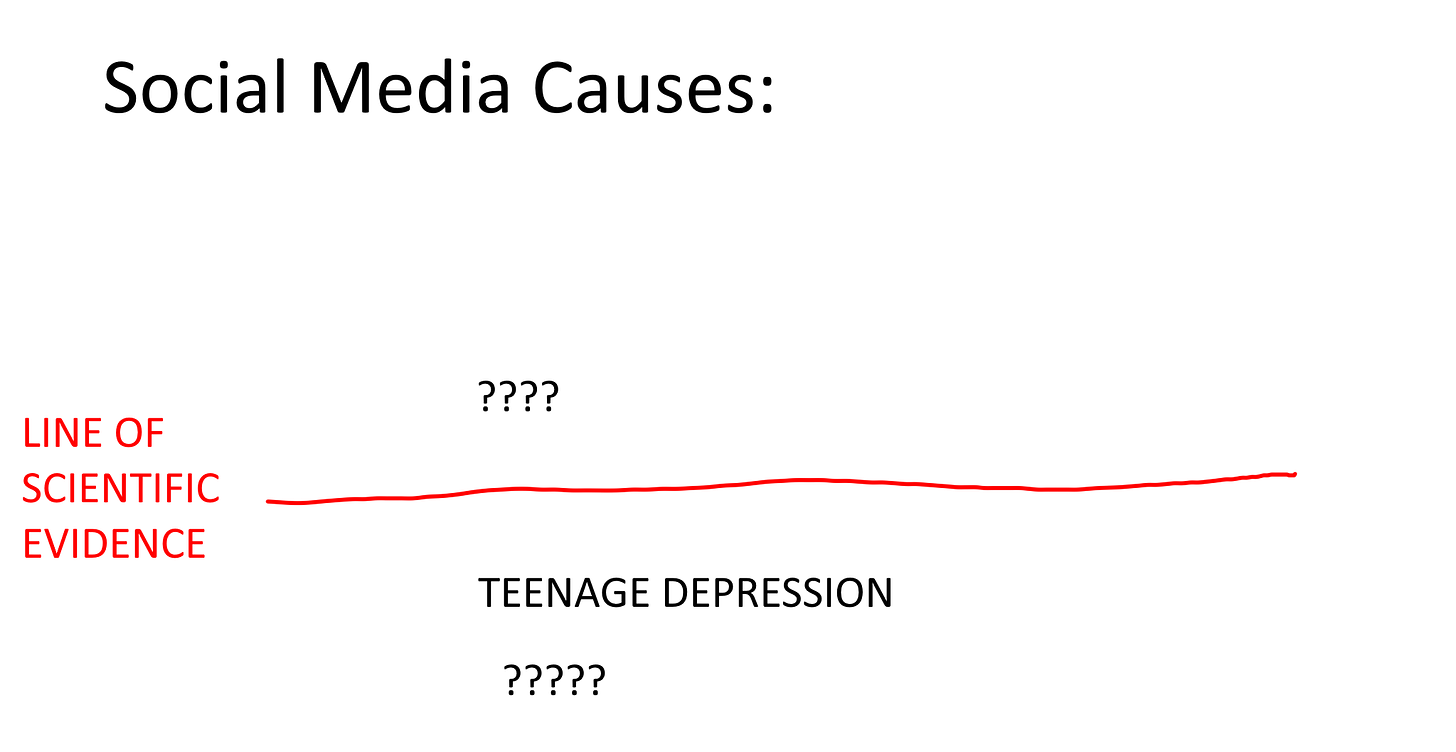

So, to run out ahead of this happening again, an open question to my colleagues studying social media: What do we know social media causes? That is, if we want to say that “teenage depression” is below this line, what can we put above it?

It’s possible that we don’t yet have an answer that meets rigorous scientific standards of evidence, that there’s nothing we can put above this line. But if that’s true, it seems important to keep that in mind whenever we speak to journalists or policymakers.

We must remember too that the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Even if there’s nothing we can put above the line, we are not justified in saying that “Scientific evidence concludes that social media does nothing.” And we are especially not justified in implying that our failure to produce knowledge means that any policy intervention is bad because not “evidence-based.”

I’m against “positivist nihilism” applied to massive phenomena like a decade of billions of Facebook and Instagram users. The idea that our null hypothesis should be that these platforms had no effect until proven otherwise is absurd — a bad-faith technocratic depoliticization of some of the most important issues confronting democratic politics today.

{ 35 comments }

Michael 07.03.24 at 6:06 pm

So, doing social science on this question is a category mistake (true), but we should answer the question of what social media causes anyway?

The category mistake lies in conceiving of “social media” as a causal agent distinct from the social context that shapes it and that it shapes. The correct category is history, not causality. We know that orality and literacy corresponded to historical epochs, but no one thinks print “caused” its epoch (i.e., the “Gutenberg parenthesis”). The age of print has passed into the age of networked media, but the latter are not like the cue stick hitting a billiard ball.

justme 07.03.24 at 7:28 pm

I’m confused (but intrigued) by the “misery causes Facebook” line. I read the post linked immediately after it and don’t feel particularly enlightened.

Probably I’m missing an obvious reading of that line, but I don’t know quite what to make of it. Can someone unpack it slightly for someone less deep in the weeds of this social science discourse?

Brian 07.03.24 at 9:49 pm

I agree with you in substance. And I will note that “social sciences” are NOT science. They never were, and never can be, because it is impossible for the observer to be apart from the observed. The observer is always part of society, and changes it by observing, hypothesizing, (then calling the hypotheses fact when it isn’t even theory) and making recommendations on that basis. Plus, so many times the data upon which conclusions are drawn is, in a word, codswallop—made up from whole cloth, or filtered to show what is desired. This is why doing things based on some social scientist’s work is so often horrific in its effects. Think Marxism.

Computer science isn’t science either, any more than mathematics or language are science. Computics has been proposed, and I favor that. But I’m not sure what one could call “social science” except social narrative exploration.

Anyway, I think it’s blindingly obvious that children and childhood are being wrecked by cell phones and social media. So are institutions, politics, and discourse. I can’t remember the name of the author that wrote a sci-fi story about a planet that succumbed to “cultural fugue” and everyone had died except a man who had been surgically altered so he had no sense of self and didn’t care what happened to himself—a slave in his society. The description of cultural fugue was prescient, and describes what happens now, in larger and larger waves.

Alex SL 07.03.24 at 10:35 pm

One thought that immediately occurs to me is that “social media” is not a single thing. The dynamics of a network for sharing short text snippets (“microblogging”?), even at its worst, are different from those of a network for sharing short video clips, even at its worst. I mean, ResearchGate is a social media site. Hypothetically, it could well be possible that given two different networks and an identical network of users, one of them could cause anxiety and the other didn’t. Second, there is a massive difference in whether we are thinking about people who consume what they see on the network or those who are actively trying to build a brand or social media identity for themselves, as the latter brings additional stressors.

To that adds the third thought that the dynamics of the network are only a minor part of the whole; the content is IMO much more important. I am not generally monitoring my emotional state using a scoring scheme, but even I notice how much more I get annoyed when reading Twitter since Musk brought his very particular genius to bear on the company. Where previously I had a nice scroll through some news and announcements from colleagues, these days the dominant impression is threads of dozens of right wing trolls and climate deniers, generally characterised by a combination of nastiness, extreme self-confidence, and complete absence of evidence and argument. The logical consequence is that my optimism and faith in humanity take a dive whenever I spend some time there, and I therefore have drastically reduced my exposure to this particular social medium and started reading more newsletters/blogs. But it wasn’t the design of the network structure that changed.

By extension, it seems obvious to me that anxiety or depression in young people may not necessarily be caused by an algorithm in itself but by the specific information they are getting, including information that they would still get even if, say, Tiktok was shut down. Hard to see how news on Gaza, the rise of the far right in Europe, or the increasing impacts of global heating would not affect an empathetic teenager even they got that from a TV or radio instead of a system where they can hit ‘frowny emoji’ or ‘like’ in response.

Claude Fischer 07.03.24 at 11:28 pm

Two comments:

1. There is much to commend in this post. But one problem is the repeated language of “social media causes….” Social media causes nothing; USE of social media may cause many things. It is important to keep in mind that we are talking about the use of the technology, not the technology. That opens different avenues of research.

2. We actually have lots of data on substantive consequences of the use of social media. It’s just not about the social problem issues that have been raised. For example, there is good data that using social media allows older people to stay in touch with family and friends; people in special interest groups finding associates; people getting information on medical issues; etc. It’s the complications around linking use of social media to psychological problems of youth where the models and data are pretty mushy.

Luis 07.04.24 at 3:06 am

Ugh. A longer comment got eaten, but TLDR: it’s fine (and appropriate) for parents and schools to strictly control their own kids, and the state should probably do some carefully controlled nudging of the tech industry to make that easier. (Apple’s scandalously buggy parental controls, and refusal to allow dumbphones to interop with their messages, should both be front and center of FTC and Congressional investigation.)

But Haidt’s advocacy of mandatory age verification by websites is 100% authoritarian stuff that the far right will use, as soon as it is implemented, to block kids (and eventually adults) from accessing information about abortion, contraception, and whatever else they deem dangerous. That Haidt doesn’t see that, or doesn’t want to admit it, makes him culpable.

MisterMr 07.04.24 at 10:46 am

Is there any proposed causal explanation for the link between social media and anxiety?

It is well possible that kids become anxious because of [whatever] and as a consequence go to social media, instead of the opposite.

Without a proposed causal explanation it doesn’t make sense to, say, block all social media at random.

Ray Vinmad 07.04.24 at 12:07 pm

Setting aside the misinformation problem, what if social media mainly introduces us to a lot more information about the world, and a lot of it is worrisome.

What if this makes people depressed?

It makes me depressed.

I vividly recall certain times when reading the newspaper or magazines have contributed to feeling depressed. E.g., during the various wars the US has waged, I would read the newspaper and cry. Likely, the fact there was only so much one could read about these events limited my despair. I would have to put the reading material down, and go live my life.

Social media is an endless feed of the terrible. Misery and ominous portents for the future is on there 24/7. As a medium, it is worse for this–but — Why does it matter so much that it is social media?

I suppose that is your question.

A cause that could contribute to depression I could see is that the information blends with the emotional reaction of others, thus potentially heightening one’s own emotionality. The shared lamenting and collective freaking out probably does get to us.

At the same time, how preferable is it for us to lament and freak out alone?

On the assumption that it’s not so valuable to know what is happening that one becomes crippled by the knowledge, we still have a bigger question about how to balance one’s life so that one knows things, but doesn’t know so much that one is overwhelmed with the misery of the world, and the many pending threats to human beings and life on Earth that one can discover in a variety of ways now.

The medium has the endless stream, the trouble information, and it is conveyed in a particularly emotional way. Some people are probably vulnerable to being thrown into various lasting psychological states due to this. But we know even the radio can do this to people. The problem of social media is that it is always there. Certain people may have a compulsion to seek heightened emotional states so the ‘always there’ part is not a small thing.

Still, my reaction to social media doesn’t seem all that different than my reaction years ago when I was researching the history of genocides, all from books. The immersive nature of the task, and the subject matter colored everything else. Perhaps social media is like this in certain ways–immersive, and full of cases of human suffering.

But this is still an instance of ‘finding things out about the world.’

I assume this issue that the kinds of things one finds out is a cause rather than the way one finds them out (via social media) has been covered by the researchers because it is one of the main objections raised to Haidt’s arguments about social media causing depression– by people on social media. They say that it is the world that is depressing.

Are there many qualitative studies of what the youth are doing specifically?

Anecdotal evidence probably isn’t that helpful but I am partly skeptical of the Haidt view because of my observation of my own children.

I was one of those parents who was strict about social media, screens in general and cell phones especially, My oldest kid had a flip-phone up through most of high school.

My rules all fell apart during the pandemic, I don’t remember the thought process that destroyed all rules in our household, if there was one. I wanted to avoid arguing and negativity. My kids started to be on screens much more than seemed healthy. One day, as I was about to revert to my nagging mom ways, I went to lecture my children to tell them to put down their screens. But they were both looking at the screens and laughing. (I am pretty sure they were watching YouTube).

This made me hesitate. Everything seemed so grim at the time–should I grab these things away from my children while they are laughing during a very depressing period for the world? I am sure what they were watching was very dumb but it was making them laugh. I wanted them to laugh.

At this point, I have noticed about both my children that unlike their parents, they are rather averse to depressing and upsetting information or news stories. They also don’t do anything on social media like instagram that would cause them compare themselves to other children. Their consumption is mostly devoted to fiction, comedy, sports, science or history. Although the quality is a lot lower, what they’re doing doesn’t seem that different than watching television.

My kids lecture me about the way I gravitate to depressing things on social media.

There is a social aspect for my kids but at least for one of them, it seems rather beneficial. My oldest child created a whole friend group found purely through social media. Kids who liked certain TV shows and books would create discord groups, and watch these things and comment. Some of these kids have met in person, and are now quite close. They’ve also made friends with the real life friends of my child to create this blended social media plus school friend group. A couple of these kids have visited us from across the country. (In one case, we had dinner with their parents.) The ones who live nearby go out and do things together. They all talk on the phone quite a lot. Their conversations tend toward the absurd, and I hear a lot of laughing.

This child was severely depressed at one point but hasn’t been depressed for years. I think having many friends helps with this. I suspect they screen their information assiduously to avoid depression. (My mother also does this and their tactics are very similar–but my kid didn’t get this idea from my mother They even talk about screening the news in the same way.)

Rather than ban social media, couldn’t we encourage kids to learn skills like the ones my kids have somehow taught themselves–to avoid those things that make you feel terrible?

I get paternalism isn’t supposed to be wrong for kids but there’s something sketchy the government stepping in to forcibly protect them from information about the world in order to shield their delicate brains. If the target is social media, doesn’t this amount to not allowing them freedom to communicate with their peers about their own concerns? I agree with the above comment there is something fishy about this plan. I doubt it is being done for their benefit, and suspect it is done because adults have become alarmed at freedom for the youth to form their own opinions.

hix 07.04.24 at 6:31 pm

Learning how to use it got its limits when it comes to platforms ever more optimized against the user, like TikTok or Instagram. It’s not even a proper individual solution to ban one’s children from using them, either, as they end up excluded from everything.

Kenny Easwaran 07.04.24 at 6:48 pm

What I find interesting about all this is that people find Jonathan Haidt so bad as a vibe that they feel compelled not just to claim that he has no evidence for the thesis that supports his normative claim, but also to go out and suggest the very bold set of claims that the only thing social media does is give people an accurate view of the world, and that if this causes depression, it’s somehow accurate depression that everyone should have been feeling before, because the world is objectively bad.

It’s true that there is some good in the kinds of information and connection that smartphones and social media enable. But you don’t have to deny that there is any bad (even of the sort Haidt alleges!) to give arguments for resisting the normative conclusions.

Ray Vinmad 07.05.24 at 2:00 pm

Hah. I do NOT think it gives people an accurate view usually. My point is only that there IS information that is accurate such that if you ansorbed enough of it you could become depressed.

Joseph p OMalley 07.05.24 at 6:40 pm

“But Haidt’s advocacy of mandatory age verification by websites is 100% authoritarian stuff that the far right will use, as soon as it is implemented, to block kids (and eventually adults) from accessing information about abortion, contraception, and whatever else they deem dangerous. That Haidt doesn’t see that, or doesn’t want to admit it, makes him culpable.”

I agree with this. I think the pushback that Haidt gets as to do with this type of legislative intervention. If agreeing with Haidt gets you this or the TikTok ban, why agree with him.

Harry 07.05.24 at 9:30 pm

“My kids started to be on screens much more than seemed healthy.”

My biggest, of many, regrets about how I dealt with my kid in the pandemic was the several months of forcing him to look at a black screen, and trying to make him put his camera on so he could be seen, in the (in retrospect idiotic) belief that the school district was trying to use online teaching as a way of getting students to learn. The combination of my forcing and the black screen probably did him as much harm as spending time on his phone (which may not have been that bad, given that the schools were closed and for many months the county was not allowing children to interact with each other in person, and even when it was, in my city, other parents were not allowing it).

There’s quite a bit of reasonably convincing literature that allowing screens in classrooms harms learning. If you sit at the back of classrooms in which screens are allowed (which I do reasonably often) you conjecture that students are, in fact, learning something about the prices of clothing on amazon.

MisterMr 07.05.24 at 11:53 pm

Thinking about it, how does one do age verification on websites?

Does the website just ask your birthday?

I’m a fan of webcomic and a member of a pair of webcomic communities, and since some webcomics are p0rn these sites ask your age and if you are young they hide some comics.

However, it is evident that kids can easily lie and many kids certainly do lie in these cases.

How does one solve this with social media?

Should social media ask for stuff like ID cards?

And what for people who are not USAns?

engels 07.06.24 at 1:07 am

It is well possible that kids become anxious because of [whatever] and as a consequence go to social media, instead of the opposite.

If this is the case, it’s very lucky that social media was invented at exactly the time when kids all became anxious for some other reason and could jump on it.

David J. Littleboy 07.06.24 at 6:01 am

I don’t own a cell phone.

But kids are more depressed, you say.

Pshaw! I say. When I was growing up, we didn’t expect to make it to 30. Many of us (54,000 or so) didn’t due to that litany of war crimes known as Vietnam (I calculated that it was safer to be a US grunt of my generation than to be a subsistence Southeast Asian farmer during that period). It was not clear that MAD was going to work. And it really looked like a fight between the Repugs trying to make 1984 come true and something else ending the world.

The kids are fine. Tell them to shut up and get over it.

David in Tokyo 07.06.24 at 12:24 pm

FWIW, MIT seems to be on the case…

https://www.technologyreview.com/2024/06/25/1093144/smartphones-are-the-new-cigarettes/

Also, FWIW, I ride the trains in downtown Tokyo fairly regularly (off-peak, though), and while the vast majority of folks will have their noses in their cell phone, there’s almost always one or two folks reading a real book or newspaper. And this hasn’t changed in quite a while.

Aside: smaller bookstores in rural areas are having a rough time of it, but the big downtown bookstores seem to be doing fine. Amazon contracts with the used book market, so you can order used books quickly/easily. I’ve been reading about the pre-war (mostly Kyoto University school Marxist/Materialist) philosopher/social commentary types, and one bloke (Jun Tosaka) had a 10-year affair (and a daughter) with Hideko Mitsunari (who became an elected local Communist Party politician after the war) despite being married. He died in prison during the war, but when his complete works were published, one commentator wrote, in the midst of a bunch of hagiographic stuff, “while his private life was not beyond reproach”, and Ms. Mitsunari went balistic and wrote a 364-page biography of him to argue that his private life actually was beyond reproach, thank you. Anyway, said biography was published in 1977, is still in print, but I chinzed out and ordered a used copy, and it’s lovely. A first edition, no less. It even has the original publisher’s postcard so that you can send feedback to the publisher.)

Being an obnoxious twat, I attacked an older (i.e. my age) male Japanese bloke who was reading a real book while walking down the street, and said “Kou iu jidai de, katsuji wo yomu hito mada imasu ka?”, and he came back with, with hardly any pause whatsoever, “Yappari, hon ga suki desu.”. he scurried off before I could say “Me too”.

(Hey, in this day and age are there really still people reading printed materials???

Well, come to think of it, I really like real books.)

(“Yappari” is a fun word. It means “I originally thought X, but for a while went through a phase of thinking the opposite, but now I realize I had the right idea from the start.” It’s used to give the speaker an air of being serious and thoughtful, so English speakers don’t seem to have much use for such a word.)

Jan Wiklund 07.06.24 at 6:06 pm

According to Randall Collins: Transaction ritual chains, only physical transactions really count, because that is what gives humans emotional energy. This sounds like flummery, but it squares with the way humans developed talking as a method to communicate with more likes than apes did grooming eachother.

It also seems to confirm the results of all these social media sponsored protest movements which never achieved any of their goals. Social media simply couldn’t make the participants enough of a “we” to defend anything.

So I was perfectly happy when Facebook cut me out a few years ago, possibly because I had shared an article about the US senate hearings about Facebook’s business methods. I have never missed what I got there. In fact, being on Facebook was nothing but a gigantic time thief.

John Q 07.07.24 at 9:53 am

What is needed here is a control group. I’d suggest the writers and readers of Crooked Timber as having the following important characteristics

What we need now is a clever text analysis of our posts and comments. Failing that, I’ll fall back on introspection and say that I am at least as depressed as the median teenager, despite being born with an almost incurably optimistic temperament. And things really started going to hell in a handbasket around 2010, when it became obvious that the zombies were re-emerging after the GFC, and that the Obama project had been a failure/illusion

MisterMr 07.07.24 at 2:37 pm

@engels 15

For example, kids might be anxious because their parents spend too much time on social media, or because less and less families have a stay at home mom, or any other modern phenomenon. More or less every new thing that is happening in the last 20 years is contemporary with social media.

David in Tokyo 07.08.24 at 1:13 am

You think it’s the kids? Nope, it’s the grandkids who are getting the short end of the stick.

On the train the other day, I saw a family, probably tourists*, two parents and two kids. The parents had their noses in their cell phones and were completely ignoring the kids, who looked lonely and in need of attention/care.

*: Japan’s obnoxious right-wing government has an explicit policy of encouraging tourism. Which means there’s going to be a nasty Covid wave here later this month.

Sebastian H 07.08.24 at 6:40 pm

“Is there any proposed causal explanation for the link between social media and anxiety?”

This is one of the few truly original thoughts of my life, so I’m hesitant to throw it out there but:

Background: we are a highly tribal species and most of our history involved times where being ostracized meant death. So our brains are attuned in multiple directions to worry about the group of people who could ostracize us.

Social media expands our circle far beyond what our reflexive intuitions can handle. It greatly expands the group of people we think we should think about as important but it does so in an asymmetric way. It somewhat expands the group of people we think we can get comfort from, but it GREATLY expands the group of people that our brains think we need to be worried about being ostracized from. That makes a lot of people very anxious, especially if they don’t have a deep grounding in the non-social-media world.

Thats the core insight.

There are related concepts that other people have noticed: in the real world if you think something and you personally know 40 people who also think it is a great idea, it probably isn’t a truly awful thing that will get you into massive trouble. And if none of the 40 people closest to you think it is a good idea, you should probably reconsider. But on social media almost any deeply stupid idea can get you 40 likes or other forms of positive reinforcement because the world is a big stupid place. Your hardwired brain doesn’t know what to do with that, so it makes you vulnerable to conspiracies, or other rabbit holes.

engels 07.09.24 at 12:15 pm

For example, kids might be anxious because their parents spend too much time on social media, or because less and less families have a stay at home mom, or any other modern phenomenon. More or less every new thing that is happening in the last 20 years is contemporary with social media.

I don’t have time to investigate but those hypotheses could presumably be elimated by comparing the mental health of children who are on social media with those who aren’t.

steven t johnson 07.09.24 at 12:57 pm

engels@23 Middle school science teacher button pushed, sorry.

Children whose families can’t afford social media aren’t on social media. That raises the issue of familial poverty as a confounder.

Statistical controls in lieu of laboratory experiments are hard.

engels 07.09.24 at 1:06 pm

smaller bookstores in rural areas are having a rough time of it, but the big downtown bookstores seem to be doing fine

This is absolutely not the case in Britain. Eg Bristol once had a Borders, Blackwells, Waterstones and Fopp on the same street I think: all now gone.

MisterMr 07.09.24 at 4:09 pm

@engels 23

Yes, but since the OP states that there is no clear link between social media and anxiety in kids, only that the use of social media and anxiety seem to be rising together, and since there are a zillion possible causes for them both rising together, one would need a zillion of whack-a-mole studies to check what is the actual cause of the depression, unless one has a specific idea that makes it likely that anxiety is caused by exposure to social media.

Sebastian H gave his own hipothesis, but the OP didn’t. The OP links to an article (“I don’t care what the studies say”) that says stuff like “The conventional wisdom—espoused here by Osita Nwanevu—is that it is always better to look at studies than not. But what if that’s not true?” or “I don’t want to do a literature survey on phones and depression either,1 because I, and all of you who have been following along with this blog series, know the literature is an uninterpretable mess.”

So yay, let’s act on something without a shred of proof that something is bad. Won’t Somebody Please Think of the Children? As Helen Lovejoy said.

engels 07.09.24 at 5:43 pm

Doesn’t Haidt think there are other causes anyway? Iiirc his schtick was that “coddling” is bad (except for the internet where it is presumably good). That the causal debate seems hopelessly confused initially probably isn’t an uncommon experience when the interests of a multibillion industry are at stake. Imho if spending a lot of time on Twitter doesn’t make you mentally ill there’s something wrong with you.

CJColucci 07.09.24 at 6:38 pm

justme@2:

I think what the line means is that when X and Y correlate, we often jump to the conclusion that X causes Y, ignoring the possibility that Y causes X. Two examples, one silly, one not:

Smoking causes cancer. This seems reasonably well-established, but it was at least theoretically possible that a propensity for developing cancer somehow caused people to smoke. There were plenty of good reasons that no one, so far as I know, investigated the possibility that cancer causes smoking. There did not seem to be any plausible causal mechanism by which cancer-proneness would cause one to smoke and no way to test the hypothesis.

There was a study some years ago showing a high correlation between gun ownership and the likelihood of dying from violent crime. The correlation seemed sound, but what caused what? Did ownership of a gun cause one to live a shitty life in a violent neighborhood where one was far more likely to get killed, or did living a shitty life in a violent neighborhood where one was far more likely to be killed cause people who lived such lives to own guns in a, perhaps futile, or possibly self-defeating, attempt to defend themselves against the antecedent odds of violent death? Plausible causal mechanisms can be invoked either way and might be susceptible to investigation.

noone important 07.10.24 at 10:23 am

” ignoring the possibility that Y causes X.”

It could be also that Z caused both of them. If trying to identify causality makes any sense at all.

engels 07.10.24 at 5:31 pm

Does anyone here have twins?

Harry 07.10.24 at 9:07 pm

“Does anyone here have twins?”

My daughter has 3 month old identical twins. Ripe for experimentation.

nastywoman 07.10.24 at 11:23 pm

‘Ripe for experimentation’.

The experimentation was already done years ago – not only at one German UNI but in so many classrooms that the results offered nearly the same conclusion as Jonathan Haidt.

Ray Vinmad 07.15.24 at 5:15 am

Yes, some reasons not to go with ‘social media causes depression in the youth’ because of the correlation.

1) This is a social phenomenon. So the ‘causal agent’ could be very complex.

2) We have a long history of moral panics around the youth. Among the claims were—comic books causing delinquency, TV causing delinquency, rock music causing delinquency, rap music causing delinquency, punk music causing delinquency (delinquency= drug use, criminal activity, etc.).

Maybe they did, who knows. But was it ‘kids hanging out together’ that was the cause? It was overreach to ban reading material and music.

3) What are we talking about here? Communication? Back in the day, coffee was banned as a potentially revolutionary substance as all the youth were hanging out in coffeehouses, getting stirred up.

But this just brings us back to the post which is about whether this makes any sense altogether.

Jim Harrison 07.16.24 at 4:50 pm

I think I’ve seen this movie before .Jonathan Haidt reminds me an awful lot of Fredric Wertham, the guy who promoted a cultural panic over comic books and teenagers way back in the 50’s. Social media is surely an order of magnitude more transformative than Batman or Mad, so the situations aren’t really comparable. As far as the preachy tut-tutter part of the story goes, however, Haidt and Wertham were identical twins separated at birth. Distrust or just dislike of Haidt has very little to do with methodological arguments about social science and everything to do with the guy’s perceived political agenda

hix 07.16.24 at 6:33 pm

Don’t think anybody mentioned yet that we can expect both directions – both social media use causing/increasing all kind of mental health problems and use increasing when you have them.

Does anybody argue that use of social media does not go up due to non-social media caused say depression at all?

Comments on this entry are closed.