by Maria on November 30, 2019

In June last year I gave a talk at a prize launch in Cambridge. Afterwards, I talked to a young man called Jack Merritt. Clever, energetic, and idealistic in the best possible sense, he said he was involved in some kind of criminal justice project and would like to talk more about it. I didn’t quite catch what it was about but handed over my card. A week later, an invitation arrived to speak at an event he was running in the autumn. The topic was to be something about technology and justice. Jack mentioned a piece I’d written about the Internet of Things and wondered if I could do something similar, but for his audience, a mix of current and recently released prisoners taking part in an education scheme run by Cambridge University. The project was called Learning Together. It gets university students and prisoners to study criminology together, and it’s based on reciprocity and respect.

I’ve always believed in the principle of rehabilitation, of course. Sorrow, regret, forgiveness, redemption; if we don’t practice these things individually we can’t live collectively in safety and in hope. Looking at the website, it was just the sort of project we need to have and should hope people are there to run. But I had misgivings about my own moral position. Someone I love deeply had, not long before, been the victim of a serious criminal offence. The offender was now behind bars.

Some things cannot and must not be forgiven. They don’t ever go away. Trauma is outside of time. It is always now and it has always just happened, even as we learn to build more of ourselves around it to make it smaller. There is no tidy sequential way to process, resolve and forgive. It can never have not happened. We can never leave it behind. But nor can we live inside it daily and survive. I don’t know a way to wish wholeness to those who have done such wrongs and still be a person who willingly carries some of the pain of the person I love who was hurt. I carry that pain out of love and out of my own need, because it is what is given to me to do. I don’t have the right to forgive trespasses against others and nor do I want to.

And yet we cannot throw people away.

[click to continue…]

by Chris Bertram on November 24, 2019

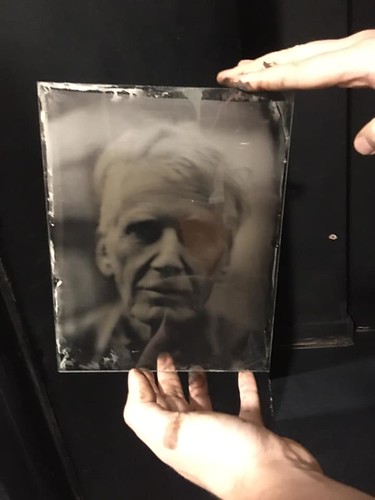

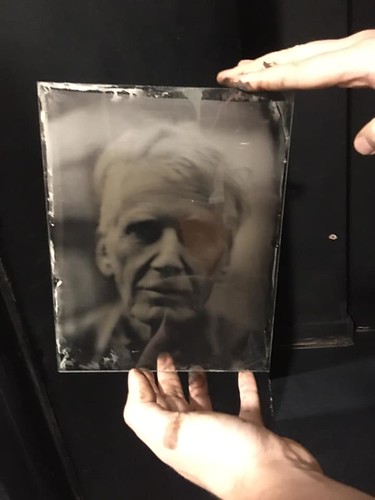

I spent yesterday at a wet-plate collodion workshop. Wet-plate collodion was the process invented by sculptor Frederick Scott Archer in 1851 and, though it became obsolete very quickly, was widely used in the United States to produced cheap tintypes, including during the civil war, and by Julia Margaret Cameron. It was quite a thing to do. First we had to clean our 8 x 10″ plates meticulously using a mix of chalk dust and alcohol and then we practised balancing and moving a marble on the plate so that we’d be ready to spread the collodion suspension acrosse the surface evenly (you tip a pool into the centre and then move it around to coat the plate without going back on yourself). Then the plate gets dipped in a silver compound to make it sensitive and it gets put into a plate holder for a view camera. The view camera (a big beast) is set up and once you are ready to expose the plate you pull on a sheet that blocks the light whilst covering the lens with something (as a makeshift shutter) and then expose for the appropriate length of time. Conditions were poor – overcast, rainy and cold – bad for the chemicals and bad for a process that relies on high levels of UV light, so my portrait (of another class member) here took 35 seconds. And then it is back into the darkroom, pouring on the developer, waiting for the image to appear and then fixing it and washing it (and hoping the delicate emulsion doesn’t just run off down the plughole). It is a direct positive process, but actually you can see the image as positive or negative depending on whether you have a black or white background behind the plate. Great fun! I’ve heard it said that there are more photographs now taken every 5 seconds than during the entire 19th century: I can see why.

by Maria on November 18, 2019

Publishing here my afterword for “2030, A New Vision for Europe”, the manifesto for European Data Protection Supervisor, Giovanni Buttarelli, who died this summer. The manifesto was developed by Christian D’Cunha, who works in the EDPS office, based on his many conversations with Giovanni.

“A cage went in search of a bird”

Franz Kafka certainly knew how to write a story. The eight-word aphorism he jotted down in a notebook a century ago reveals so much about our world today. Surveillance goes in search of subjects. Use-cases go in search of profit. Walled gardens go in search of tame customers. Data-extractive monopolies go in search of whole countries, of democracy itself, to envelop and re-shape, to cage and control. The cage of surveillance technology stalks the world, looking for birds to trap and monetise. And it cannot stop itself. The surveillance cage is the original autonomous vehicle, driven by financial algorithms it doesn’t control. So when we describe our data-driven world as ‘Kafka-esque’, we are speaking a deeper truth than we even guess.

Giovanni knew this. He knew that data is power and that the radical concentration of power in a tiny number of companies is not a technocratic concern for specialists but an existential issue for our species. Giovanni’s manifesto, Privacy 2030: A Vision for Europe, goes far beyond data protection. It connects the dots to show how data-maximisation exploits power asymmetries to drive global inequality. It spells out how relentless data-processing actually drives climate change. Giovanni’s manifesto calls for us to connect the dots in how we respond, to start from the understanding that sociopathic data-extraction and mindless computation are the acts of a machine that needs to be radically reprogrammed.

Running through the manifesto is the insistence that we focus not on Big Tech’s shiny promises to re-make the social contract that states seem so keen to slither out of, but on the child refugee whose iris-scan cages her in a camp for life. It insists we look away from flashy productivity Powerpoints and focus on the low-wage workers trapped in bullying drudgery by revenue-maximising algorithms. The manifesto’s underlying ethics insist on the dignity of people, the idea that we have inherent worth, that we live for ourselves and for those we love, and to do good; and not as data-sources to be monitored, monetised and manipulated.

[click to continue…]

by Chris Bertram on November 11, 2019

I have [another piece on the LRB blog](https://www.lrb.co.uk/blog/2019/november/architecture-of-exclusion) about the deaths of migrants in Essex recently. It was important to register a correction because early information about the nationalities of the dead was incorrect, but it also gives an opportunity to say something more about why migrants have to use people smugglers if they want to escape persecution or seek out opportunities in wealthy democracies.

by Chris Bertram on November 10, 2019

by Maria on November 9, 2019

Historic apologies get a lot of pushback, both from those who point out that saying sorry only happens when everyone who did it is dead, and nothing is ever learned, and from the fundamentally unapologetic amongst history’s apparent winners. Apologising for something you’ve just done or are about to do takes a lot more guts. But I’ve been wondering over the past couple of weeks whether Brexit negotiations with Ireland especially, and with the rest of the EU would have gone differently if at the beginning of major speeches, press conferences and working meetings the UK interlocutors had had a policy of starting with something like’

“We’re sorry. We know you didn’t ask for Brexit and that it harms you and costs you. We’re still doing it, but we acknowledge and are sorry about its unasked for consequences for others.”

And then getting on with the business of the meeting. Of course, to even conceive of acknowledging the harm and cost of brexit to others would require fundamentally different people to have been in charge. But even the act of saying this might have changed the understanding of those imposing their harms on the rest of us, and would certainly have done a lot to make other countries and institutions want to play nice. We’re emotional creatures, at the end of the day, and it’s more than just manners to acknowledge the harm we cause to others. The life you save just might be your own, etc. etc.

by Ingrid Robeyns on November 8, 2019

My colleagues put together a free MOOC that gives an introduction to the relationships between economic inequality and democracy (in particular political equality). I saw them working very hard over the months – it’s a hell of a lot of work to make a MOOC, even more so if you do this as a voluntary add-on to your regular work. Hence I’d like to salute them for their efforts, and share this with you since I’m a big fan of all things open access. I do not doubt that this will be interesting for people who are new to this question – which does not include most of the readers of this blog since we’ve been discussing these issues here repeatedly. But if you know people who might be interested, do let them now. There is no required background, and the MOOC is offered for free. More information below the fold.

[click to continue…]

by Maria on November 7, 2019

George Monbiot writes movingly about how the habit of Britain’s (well, mostly England’s) upper middle and upper classes of sending their children to boarding school from the age of seven onward causes profound emotional damage and has created a damaged ruling class. He’s not the first to notice this. Virginia Woolf drew a very clear line between the brutalisation of little boys in a loveless environment and their assumption as adults into the brutal institutions of colonialism. It’s long been clear to many that the UK is ruled by many people who think their damage is a strength, and who seek to perpetuate it.

I was at a talk last week about psychoanalysis and The Lord of the Flies. The speaker convincingly argued that much of what happens in that story happens because most of the boys have been wrenched from solid daily love before they were old enough to recreate it. It’s a pretty compelling lens to see that novel through and it reminded me of a teaching experience from a couple of years ago.

I was teaching a post-grad course on politics and cybersecurity and did a lecture on the Leviathan and how its conception of the conditions that give rise to order embed some pretty strong assumptions about the necessity of coercion. Basically how if you’re the state and in your mind you’re fighting against the return of a persistent warre of all against all, your conception of human behaviour can lead you to over-react. Also some stuff about English history around the time of Hobbes. I may have included some stills from Game of Thrones. During the class discussion, one person from, uh, a certain agency, said that yes, he could see the downside, but that Hobbes was essentially how he viewed the world.

Listening again to the tale of sensible centrist Ralph, poor, benighted (but actually very much loved by his Aunty and from a solid emotional background) Piggy, the little uns, and the utter depravity of it all – and also having forgotten the chilling final scene where the naval officer basically tells Ralph he’s let himself down – something occurred to me.

Lord of the Flies is many people’s touchstone for what would happen if order goes away, even though we have some good social science and other studies about how, at least in the short to medium term, people are generally quite altruistic and reciprocally helpful in the aftermath of disaster. Lord of the Flies is assumed by many to be a cautionary tale about order and the state of nature, when in reality it’s the agonised working out of the unbearable fears of a group of systematically traumatised and loveless children.

Lord of the Flies isn’t an origin story about the human condition and the need for ‘strong’ states, though we treat it as such, but rather is a horror story about the specific, brutalised pathology of the English ruling class.

by Chris Bertram on November 3, 2019

by John Q on November 2, 2019

The comments thread on my WTO post raises the much-argued question of whether the term “neoliberalism” has any useful content, or whether it is simply an all-purpose pejorative to be applied to anything rightwing. O

In this 2002 post from the pre-Cambrian era of blogging, at a time when I aspired to write a book along the lines of Raymond Williams’ Keywords, I claim that neoliberalism is a meaningful and useful term, which isn’t to deny that it’s often used sloppily, like all political terms.

Some thoughts seventeen years later

First, this definition refers to the standard international use of the term, what I’ve susequently called “hard neoliberalism”, represented in the US by the Republican Party. I subsequently drew a distinction with “soft neoliberalism”, which corresponds to US usage where the term is typically applied to centrist Democrats like the Clintons. I’d also apply this to Blair’s New Labour, although, as stated in the post, there were points at which Blair and Brown drifted back in the direction of traditional social democracy.

Second, the discussion of how the right (in Europe and Australia) is shifting away from neoliberalism towards “the older and more fertile ground of law and order and xenophobia” seems as if it could have been written today. These processes take a long time to work themselves through.

As a corollary, the idea of Trump as a radical break with the past is unsustainable. There’s been a qualitative change with Trump and the various mini-Trumps, but the process was well underway before this new stage.

Finally, my characteristic overoptimism shows up in various places.

[click to continue…]

by Chris Bertram on October 27, 2019

by Chris Bertram on October 24, 2019

Yesterday morning, 39 migrants, now revealed to be Chinese nationals, were discovered dead in a transport container in Essex, England. Politicians were not slow to give their opinions about who was responsible, even though it is on ongoing murder investigation. [I have a short piece on this case](https://www.lrb.co.uk/blog/2019/october/contempt-for-human-life) at the London Review of Books blog.

by Chris Bertram on October 22, 2019

I went to see occasional Timberite Astra Taylor’s remarkable film *What is Democracy?* last night. It takes us from Siena, Italy to Florida to Athens and from Ancient Athenian democracy through the renaissance and the beginning of capitalism to the Greek debt crisis, occupy and the limbo life of people who have fled Syria and now find themselves stuck. It combines the voices of Plato and Rousseau with those of ordinary voters from left and right, Greek nationalists and cosmopolitans, ex-prisoners, with trauma surgeons in Miami, Guatemalan migrants in the US, with lawmakers and academics, and with refugees from Syria and Afghanistan. All the while it poses the questions of whether democracy is compatible with inequality and global financial systems and the boundaries of inclusion.

Some of the testimonies are arresting: the ex-prisoner turned barber who tells us of his nine years in a US prison of a hunger strike when the authorities tried to take the library away and of his problems adjusting to life of the outside, to being around women, and the fact that he’s denied the vote. And all the time he’s telling you this with attention and passion he’s clipping a customers beard, which adds a note of tension. We hear from trauma surgeons who tell us of the levels of violence in Miami – so much blood that the city is used for training by medics from the US military – and the shock of cycling from one neighbourhood to the next and experiencing swift transitions from opulence to utter destitution. We hear from a young Syrian woman who relates how she had to leave Aleppo after her mother was wounded by a stray bullet in her own home and whose idea of democracy is a country where she can lie safely in her bed.

[click to continue…]

by Chris Bertram on October 20, 2019

From yesterday’s march.Tragically, the UK now is probably the member state with largest group of people who are enthusiastic about being part of the EU, and are critically aware of its shortcomings (as this placard tells us). Not a great photograph, but a record of an event. [Dipper and Stephen are banned from commenting on my threads.]

by Ingrid Robeyns on October 12, 2019

Almost ten years ago, Chris wrote a blogpost announcing that the last issue of Imprints had been sent to the subscribers. Political philosophers beyond a certain age had greatly enjoyed the articles, bookreviews and interviews published by Imprints, but it was not possible to continue. But we should not forget – and this post is merely a reminder for us not to forget – that the entire Imprints‘ Archive is online.

I was reminded of this yesterday, when I went to a lecture by Elizabeth Anderson in Amsterdam, who – to my surprise – during her talk endorsed limitarianism. Chris remarked on FB that this was a departure from her earlier views in which she merely supported sufficientarianism. The 2005 interview with Anderson in Imprints seems to support Chris’ observation, since she said (p. 15) the following:

‘Some people care about getting lost of this stuff [that doesn’t matter from a political point of view]. Once citizens’ satiable interest in securing social equality are satisfied, and he system secures for all a decent chance to get more, the state has no further interests of justice in micromanaging how the gains from cooperation are divided.”

[click to continue…]