As a reward for my sins, I read this review of Daniel Dennett’s latest, by David Bentley Hart. (My efficiently causal sin being: reading The Corner.) [click to continue…]

From the category archives:

Academia

Prominent libertarian jurist Alex Kozinski has been accused of sexual harassment by six women, all of them former clerks or employees. One of the women is Heidi Bond. In a statement, Bond gives a fuller description of Judge Kozinski’s rule, sexual and non-sexual, in the workplace.

One day, my judge found out I had been reading romance novels over my dinner break. He called me (he was in San Francisco for hearings; I had stayed in the office in Pasadena) when one of my co-clerks idly mentioned it to him as an amusing aside. Romance novels, he said, were a terrible addiction, like drugs, and something like porn for women, and he didn’t want me to read them any more. He told me he wanted me to promise to never read them again.

“But it’s on my dinner break,” I protested.

He laid down the law—I was not to read them anymore. “I control what you read,” he said, “what you write, when you eat. You don’t sleep if I say so. You don’t shit unless I say so. Do you understand?”

The demands may seem peculiar, but the tyranny is typical. Employers control what workers read, when workers shit, all the time.

But Judge Kozinski has the added distinction of being one of the leading theoreticians of the First Amendment. And not just any old theorist but a libertarian theorist—he has a cameo in the film Atlas Shrugged: Part II—who claims that the First Amendment affords great protection to “commercial speech.”

Where other jurists and theorists claim that commercial speech—that is, speech that does “no more than propose a commercial transaction”—deserves much less protection than political or artistic speech, Kozinski has been at the forefront of the movement claiming that the First Amendment should afford the same levels of protection to commercial speech as it does to other kinds of speech. Because, as he put it in a pioneering article he co-authored in 1990:

In a free market economy, the ability to give and receive information about commercial matters may be as important, sometimes more important, than expression of a political, artistic, or religious nature.

And there you have it: Watching a commercial about asphalt? Vital to your well-being and sense of self. Deciding what books you read during your dinner break? Not so much.

Government regulations of advertising? Terrible violation of free speech. Telling a worker what she can read? Market freedom.

Around November, I declare a ban on any new/borrowed books and try and finish all the books I’ve started that year. Slow-going, this year, as I was for some reason unable to read for much of October and November, and lots of the unread pile is non-fiction. Anyway, some highlights of the year, below. Another post to follow on what’s on the Christmas list.

A book that lingered in mind long after I’d finished it was Laline Paull’s fascinating The Ice (The Bees is still one of my favourite books of the last decade, and I pressed copies of it into two more people’s hands this year.) The Ice is set in the very near future, about the friendship between two men who each want to save the last bit of the Arctic. The chapters begin with excerpts from the memoirs and letters of others who have been obsessed with Arctic exploration, drawing out the historic roots of our drive both to explore and exploit.

Recently I listened to a LRB Cafe event podcast with China Mieville from about 2014. He mentioned something about “…extruded-literary fiction product which is about the calm, chapter by chapter decoding of a never very mysterious metaphor to clarify what life is a bit like, and the book ends with a ‘yes, that’s so true’, that is very wise’.” We all pretty much know what that is, when we see it. I can’t be the only one hungry for novels about politics, money, the environment, the movement of people and surveillance capitalism. Laline Paull’s The Ice grapples with several of these, and the world of work, which is quite rarely found in fiction, and the deals individuals make with themselves and the world they find themselves in, and whether we have any business holding onto hope. [click to continue…]

Benjamin Black has one thing in common with Sharon Bolton.

Black (the second of the ‘only counts as British because all Irish people who accomplish impressive things get claimed as British unless, of course, those impressive things involve some sort of successful military or political action against the British’ crime writers) is, in fact, John Banville. He seems to have shifted more or less whole hog from literary fiction to crime-writing under his pseudonym. The main series is about Quirke, a pathologist with a labyrinthine family life, and who seems to be a magnet for murder (Now I think about it I suppose pathologist is a job to avoid if you want to avoid all contact with murder). Christine Falls starts us off in mid-fifties Dublin, which is exactly the way that Henry and Maria sometimes suggest in their posts, and proceed chronologically. They are noir-ish in the extreme – it always seems to be grey and drizzling, and Quirke is depressive and not particularly likeable (his daughter is, but it is hard to see her growing toward a happy fulfilled middle-age, much as he would like that for her). They’re well-plotted, but that’s not the reason to read them – the characters and the mood, and the outlook on the world are what make them so compelling. Black actually has a wry sense of humour, but he chose the pseudonym for a reason: they are dark books. (I haven’t yet read the more recent — books).

[click to continue…]

At the APA blog Steven Cahn says:

The term “hidden curriculum” refers to the unstated attitudes that are often communicated to students as a by-product of school life…. [At graduate school]

[One] message is that faculty members are entitled to put their own interests ahead of those of their students. Consider how departments decide graduate course offerings. The procedure is for individual professors to announce the topics of their choice; then that conglomeration becomes the curriculum. The list may be unbalanced or of little use to those preparing for their careers, but such concerns are apt to be viewed as irrelevant. The focus is not on meeting students’ needs but on satisfying faculty desires.

Similarly, in a course ostensibly devoted to a survey of a major field of philosophy, the instructor may decide to distribute chapters of the instructor’s own forthcoming book and ask students to help edit the manuscript. Whether this procedure is the best way to promote understanding of the fundamentals of the announced field is not even an issue.

I think he exaggerates a little: certainly in my department more thought than that is given than he describes to graduate course offerings. But I don’t think he exaggerates a great deal. A piece of evidence: I was struck, in my several years on my university’s curriculum committee (which vets all new course proposals and all proposed course deletions in the university — at least several hundred a year of the former, and a handful of the latter) how often the rationale for proposed undergraduate courses in the humanities and (to a lesser extent) social sciences was something like this:

[click to continue…]

Following a “related stories” link, I found a 2014 piece from Dana Milbank which combines my favorite pet peeve, the Generation Game, with everyone’s favorite fallacy, No True Scotsman. I’m a bit late to the party, but I can’t resist such a tempting target.

Milbank wants to make the case that, unlike the great conciliators of the past and the cool, detached Generation X of which he is a member, Baby Boomers are given to a “scorched earth” conflict-driven style of politics. There’s just one problem. Most of Milbank’s villains (Pelosi, McConnell, Reid) were born before the baby boom, while the hero of his piece, Obama, is, sad to say, a Boomer. No problem, says Milbank, “generational boundaries are inexact”. Applying the No True Boomer test, Pelosi, McConnell, Reid are turned into Boomers, while Obama is promoted into Generation X. In these cases, the shift is only a year or so, but a moment’s thought would have provided Milbank with plenty of examples of scorched-earthers born five years or more outside the Baby Boom (Roger Ailes and Rupert Murdoch at one end, Ted Cruz and Paul Ryan at the other) and compromisers born in the middle of the Boom (Tim Kaine and the leading members of the DLC)

More to the point, the style of politics he’s talking about got its start with the Nixon-Buchanan Southern strategy “tear the country in half, and take the bigger half“. The fact that many of its most prominent practitioners are (mostly male) Boomers follows from the fact that they are currently the right age (roughly 55 to 70 depending on details) to occupy senior leadership in US politics.

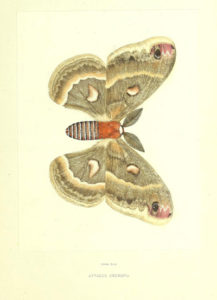

If you are like me, you have Abebooks ‘wants’ out there – hopeful lines dragging through the stream of books. Here’s one that nibbled, but it’s still too rich for my blood. It’s As nature shows them : moths and butterflies of the United States, east of the Rocky Mountains : with over 400 photographic illustrations in the text and many transfers of species from life, by Sherman F. Denton (1900). Only $400. (Anyone wants to buy it for me?)

It’s an amazing curiosity in the history of color printing. I would love to see it in person. But for now the Internet Archive will have to do. What makes it so remarkable, you ask?

From the Preface:

The color plates, or Nature Prints, used in the work, are direct transfers from the insects themselves: that is to say, the scales of the wings of the insects are transferred to the paper while the bodies are printed from engravings and afterward colored by hand. The making of such transfers is not original with me, but it took a good deal of experimenting to so perfect the process as to make the transfers, on account of their fidelity to detail and their durability, fit for use as illustrations in such a work. And what magnificent illustrations they are, embodying all the beauty and perfection of the specimens themselves!

As I have had to make over fifty thousand of these transfers for the entire edition, not being able to get any one to help me who would do the world as I desired it done, and as more than half the specimens from which they were made were collected by myself, I having made many trips to different parts of the country for their capture, some idea of the labor in connection with preparing the material for the publication may be obtained.

I’m sure someone can make use of this peculiar mode of auto-iconographic representation for some weird Wittgenstein philosophy of language example.

When I’m writing a letter of recommendation for an undergraduate applying for graduate school (one of the many parts of my job for which I have received no training and my skill in which has never been assessed by anyone), I pretty much always want to look at the personal statement (or, their answers to the program-specific questions which many professionally-oriented programs ask). If I don’t know the student really well, the personal statement helps me write the letter, just because it keeps them fully in my head; and if I do know the student really well it seems wrong not to offer to comment on/offer editorial advice, especially if I know (as I often do) that the student doesn’t have a parent who will be able confidently to do this. For all I know my own confidence is misplaced, but I don’t think it is – I have read thousands of personal statements over the years {mainly for nursing school, clinical psych, teacher ed, school counseling, medical school and law school and, of course, philosophy), and although I only know directly what other people (my immediate philosophy colleagues) think about the statements of students who apply to Philosophy PhD programs, I have observed the fate of those students whose statements I’ve looked at.

The main thing I want to say about personal statements is that in my experience many candidates agonize over them and spend far too much time trying to get them exactly right. In philosophy the main purpose of the personal statement is to convey that you know what you are doing, that you are genuinely interested in the program you’re applying to, and that you are not a complete flake. Some people, it is true, have genuinely interesting stories behind their desire to X, whatever it is, but most really don’t.[1] But they usually seem compelled to tell a story as compellingly as possible. Here’s a quote from a recent email (used with permission):

Hi Brighouse, I hope you had a nice weekend and that you have a good week ahead of you! I wanted to email you to ask for your help with my personal statements. I have spent a lot of time attempting to write some of them and I am really struggling. They feel very cliched to me and I am not sure how to make myself stand out as an applicant in so few words!

Clerihews explained here.

This week, we have a sporting edition. Now, there is a slight problem here: I am only interested in one sport. However, my son’s irrational obsession with American Football has at least provided me with one subject (and my son, to my surprise, approved).. And I think I may have composed the first ever clerihews about women cricketers. You, the readers, are entirely welcome to write clerihews about one of the lesser sports — indeed, I hope you will!

Football:

Ha Ha Clinton Dicks was cursed

With a name that made him burst

Out with laughter whenever it was said

So he changed his name to Fred instead.

Cricket:

Elyse Perry

Makes Australians merry

As she dashes

England’s hopes to regain the Ashes

Than Moeen Ali, the spinner

Few cricketers were ever thinner;

Beefy and Freddie in fact

Were, not infrequently, fat.

Boycott was never out

But he wouldn’t clout

A ball for six

Even when his team was in a fix. [1]

Geoffrey never scored runs too fast

In matters of style he was often outclassed

But with steely rumination

He went about accumulation

When considering Alex Blackwell

The selectors have not checked their facts well

She scores tons of runs, so in the absence of Lanning

Why the hell isn’t she Australia’s captain? [2]

[1] He actually did hit eight 6s in Tests, half of them in 1973.

[2] This one was, obviously, written before the start of the Ashes series.