by Harry on January 15, 2012

Guardian obit here. Whenever I have written about mysteries on CT, Henry has put in a word for Reginald Hill. Quite rightly: by the late eighties Hill was one of the 3 or 4 best mystery writers in the English language, and, of that group, the most effortlessly enjoyable (the others?: James, Barnard, and, until he died, Symons. Go on, tell me I’m wrong). He is most famous for his Dalziel and Pascoe books, mainly for the combination of complex plotting, interesting delightful characters, and many very comedic moments. The first 5 or 6 are fairly straightforward whodunnit/police procedurals (with the exception of Deadheads

books, mainly for the combination of complex plotting, interesting delightful characters, and many very comedic moments. The first 5 or 6 are fairly straightforward whodunnit/police procedurals (with the exception of Deadheads which defies one of the central conventions of the whodunnit), but one reason Hill became so good is that he experimented, frequently, in the novels, with style, format, and, increasingly often, convention. Most of his non-series books (his other series about Joe Sixmith, a black detective in Luton, was much more relentlessly humorous) were written in the 70s and early 80’s, often under pseudonyms (he has published under at least 4 names, maybe more), before he got to be really good. But the last two were brilliant, especially The Woodcutter

which defies one of the central conventions of the whodunnit), but one reason Hill became so good is that he experimented, frequently, in the novels, with style, format, and, increasingly often, convention. Most of his non-series books (his other series about Joe Sixmith, a black detective in Luton, was much more relentlessly humorous) were written in the 70s and early 80’s, often under pseudonyms (he has published under at least 4 names, maybe more), before he got to be really good. But the last two were brilliant, especially The Woodcutter , which is riveting, as good as any of the Dalziel/Pascoe books.

, which is riveting, as good as any of the Dalziel/Pascoe books.

Or as good as any so far. Honestly, I was expecting him to live another 15 years at least, yielding 5 or 6 more, so was sickened when I read my mum’s email this morning, which started “No more Dalziel..”. But, according the wiki page, there is one more to come, which this amazon.co.uk page seems to confirm. So, one more to come.

seems to confirm. So, one more to come.

by John Holbo on January 9, 2012

Several years ago I read – and posted about – a book I quite enjoyed: Roads To Ruin, The Shocking History of Social Reform (1950), by E.S. Turner. (Reasonably inexpensive used copies available from all likely sources.)

It’s basically a survey of forgotten British moral panics of the 19th and early 20th Centuries. Predictions of the death of decency and/or fall of Western Civilization meet social reform proposals that sound (to us today) right and proper, or at least reasonable, or at least unlikely to bring about apocalypse.

Daylight savings. Should the ban on marrying your dead wife’s sister be lifted? Should spring guns be banned? Should children be forbidden to buy gin (for their parents, not themselves) in pubs? (You might think that the panic was over a proposal to let children buy gin. But no.)

It’s in the minor nature of these cases that, 30 years on – let alone 150 years – we forget these were hot-button culture war issues. Suppose we were to rewrite Turner’s book today. What cases can you come up with? Now-forgotten moral panics in the face of social reforms enacted in, say, the last 75 years?

No-fault divorce and legalized birth control are good examples. Same-sex marriage is going to grow up to be an example, I’m reasonably sure. But the genius of Turner’s book is that his cases are so minor. Birth-control and easy divorce were big deals, socially. Opponents were right about that much. Letting men marry their dead wive’s sisters, by contrast, was never going to make a big difference. What recent examples can you think of that are more like the latter? I’m looking for cases in which politicians and pundits and and so forth really got into the game. It’s a big hand-wringing public End Is Nigh botheration. And, in retrospect, it’s not just wrong-headed but fantastically silly.

It’s more common, I suppose, to get these sorts of moral panics about some new thing the kids are up to. Dungeons and Dragons is turning children into satanists. (Ah, those were the days.) Let’s try to restrict ourselves to cases in which social reformers, not the kids, are the targets. What have you got for me?

by Henry Farrell on January 4, 2012

Since John wrote his post below, Mark Lilla has come out with a “lengthy attempted rebuttal”:http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2012/jan/12/republicans-revolution/?pagination=false of Corey Robin’s argument. Even as New York Review of Books articles by creaky centrist-liberals go, it’s a terrible essay – see further “Alex Gourevitch”:http://jacobinmag.com/blog/2012/01/wrong-reaction/. Even as _Mark Lilla essays on the American right_ (a category that includes a plenitude of incompetent arguments) go, it’s awful. Two things that I think are worth adding to Alex’s takedown.

[click to continue…]

by John Holbo on December 21, 2011

Following up my previous post, here are some free PDFs. Enjoy (or not). I’ve tried to optimize these for the iPad. I would be interested to hear about any problems/unsatisfactorinesses, perhaps due to the fact that you are using a Kindle or whatever. [click to continue…]

by John Holbo on December 21, 2011

I’d like the survey the CT commentariat about their ebook reading habits, and toss out a few ideas. I’ve made the shift this year. I now read more new books on my iPad than on paper. I also read a lot of comics on the iPad, mostly courtesy of the Comixology app. But let’s start with plain old mostly word productions. [click to continue…]

by Belle Waring on December 20, 2011

Katha Pollit on Hitchens (yes, yes, I’ll stop now). She doesn’t hold her fire. Via Lindsay Beyerstein

Update of sorts: there are lots of high-functioning alcoholics in the world. They manage to keep it together for a long time. When do they come to AA? When they’re 65. What was it like for his family to have to deal with him dying as an active alcoholic? I’ve seen it and it isn’t pretty.

by Maria on December 14, 2011

I have to share this. My thirteen year-old god-daughter, Aifric, loves a good read, but I don’t always hit the mark. I like to give her books I loved myself at that age, but also to try out new ones. A few weeks ago, I sent her the Bad Karma Diaries, though not till after I’d read it myself. (I’d picked it up because it’s by an old friend, Bridget Hourican).

The Bad Karma Diaries is about two girls going into their second year of secondary school, Anna and Denise, or rather Bomb and Demise, in text-speak. They decide to start a business, and a blog, and then also a karma exchange for the bullies and bullied kids in their school. It all goes horribly wrong; adventures are had, lessons are learnt, ways are mended – somewhat – but there’s no moralising at all.

The verdict? “I loved it I loved it I loved it! :D Is there a sequel?? :)”. I’ve had a few misses as we navigate the tricky reading years between much-loved children’s stories and those first steps of her reading grown-up books for real. So it’s very nice to have really hit the spot. If you are looking for a funny, clever, non-preachy but still very enlightening book for the young teenager in your life, look no further.

For Aifric’s birthday next year, I’m thinking of sending Jo Walton’s gorgeous Among Others. If, as they say, Harry Potter is about confronting your fears and doing the right thing, and Twilight is about the importance of keeping your boyfriend, Among Others is about the joy of reading (especially SF & fantasy), surviving loss, thriving as a fish out of water, and the inherent value of thinking long and hard about people in your life, both good and bad. Not just for adolescents, then.

Any thoughts on books – especially recently published ones – for 12-14 year old girls or boys?

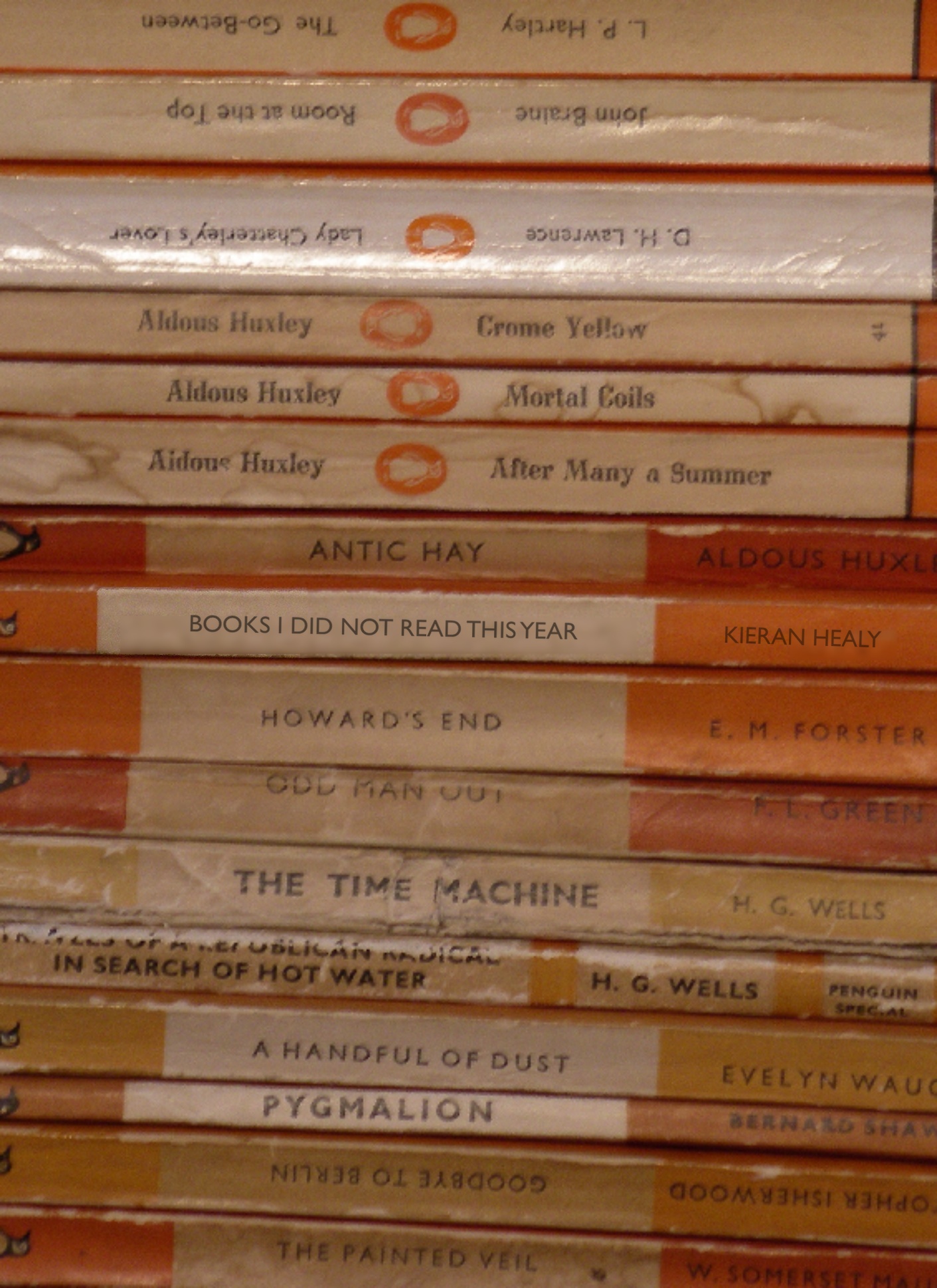

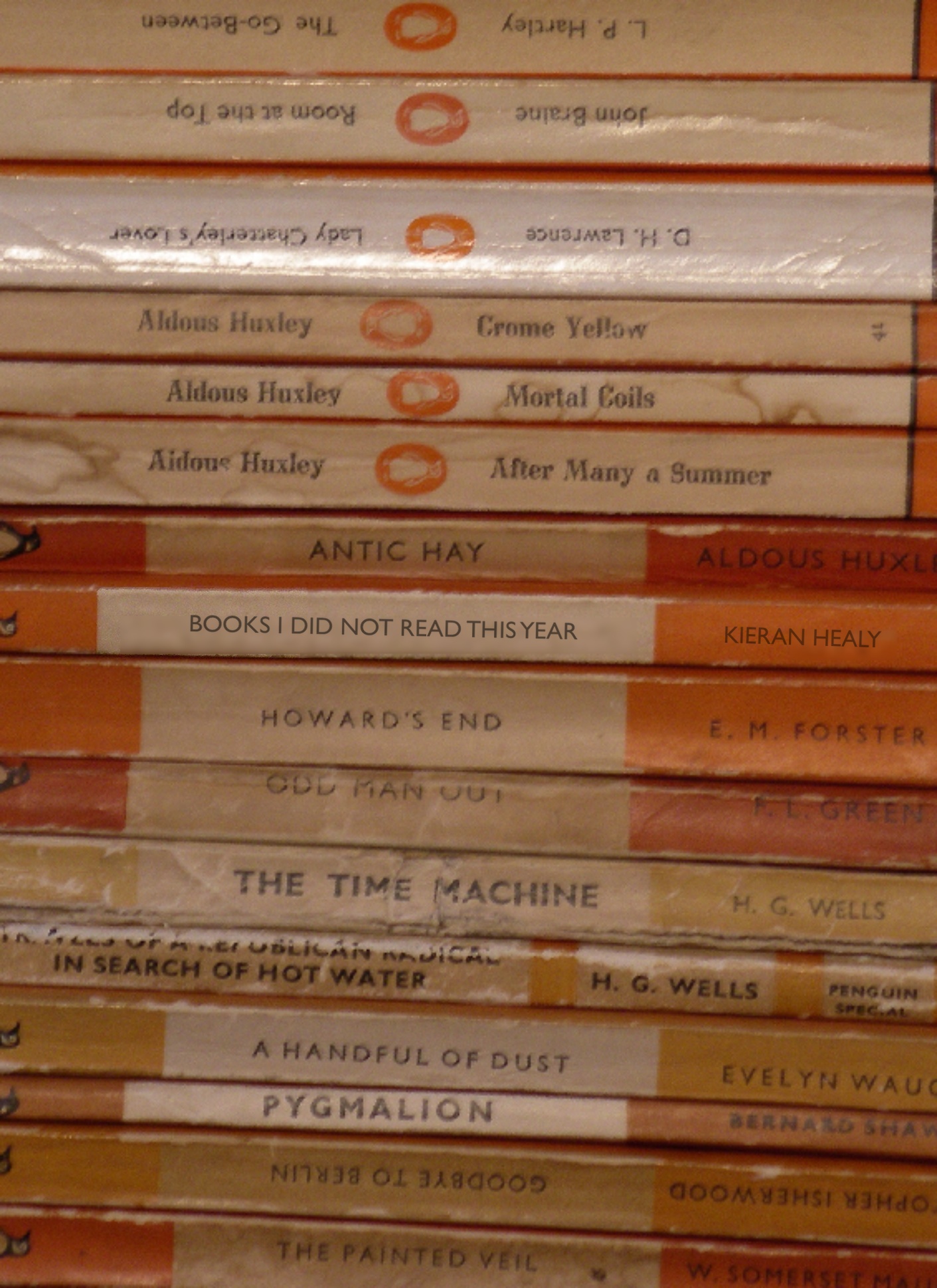

by Kieran Healy on December 9, 2011

I’ve been using the Readmill ebook reader on-and-off. I like it quite a bit. Using it prompted me to make an ebook of my own. Because I moved my own website over to Octopress a little while ago, everything I’ve ever written on it going back to 2002 is now in Markdown format. So over lunch yesterday I took advantage of John MacFarlane’s amazingly useful Pandoc, which can make EUPB format ebooks out of markdown files, selected thirteen posts from the Archives and made a little anthology called Books I Did Not Read This Year (epub). It’s free to download, because I’m such a generous person. Enjoy it on Readmill, iBooks, your or any other EPUB-compatible reader. Daniel kindly made a Mobi version for Kindle owners. I plan on making a few more of these, forming a Press (e.g. “Harbard University Press” or “Pengiun”), and then adding them to my Vita.

by Ingrid Robeyns on November 29, 2011

by John Q on November 15, 2011

A couple of requests for CT readers

- I’m running a half-marathon in Philadelphia at the weekend and raising money for an East Africa Famine appeal in Australia. The Australian government will match donations dollar for dollar, and you may also be able to claim a tax deduction, so this is a real bargain. You can sponsor me here – I’m currently a dollar short of halfway to my target of $5000

- I’m writing a piece about social democratic responses to what Colin Crouch has called the “strange non-death of neoliberalism“, and I’m looking for books that focus on restoring more equality in market incomes, for example by rebuilding unions or constraining the financial sector, as opposed to redistribution through the tax/welfare system. Any suggestions would be much appreciated.

* I’ll ask nicely, but I refuse to bl*g

by Henry Farrell on November 8, 2011

Chris’s “post below”:https://crookedtimber.org/2011/11/08/a-new-communist-manifesto/ reminds me that I’ve been meaning to disagree with this “claim”:http://www.roughtype.com/archives/2011/10/utopia_is_creep.php by Nick Carr.

bq. Works of science fiction, particularly good ones, are almost always dystopian. It’s easy to understand why: There’s a lot of drama in Hell, but Heaven is, by definition, conflict-free. Happiness is nice to experience, but seen from the outside it’s pretty dull.

bq. But there’s another reason why portrayals of utopia don’t work. We’ve all experienced the “uncanny valley” that makes it difficult to watch robotic or avatarial replicas of human beings without feeling creeped out. The uncanny valley also exists, I think, when it comes to viewing artistic renderings of a future paradise. Utopia is creepy – or at least it looks creepy. That’s probably because utopia requires its residents to behave like robots, never displaying or even feeling fear or anger or jealousy or bitterness or any of those other messy emotions that plague our fallen world.

[click to continue…]

by Chris Bertram on November 8, 2011

At The Utopian there are details of a project by Adorno and Horkheimer for a new Communist Manifesto:

bq. Horkheimer: Thesis: nowadays we have enough by way of productive forces; it is obvious that we could supply the entire world with goods and could then attempt to abolish work as a necessity for human beings. In this situation it is mankind’s dream that we should do away with both work and war. The only drawback is that the Americans will say that if we do so, we shall arm our enemies. And in fact, there is a kind of dominant stratum in the East compared to which John Foster Dulles is an amiable innocent.

bq. Adorno: We ought to include a section on the objection: what will people do with all their free time?

bq. Horkheimer: In actual fact their free time does them no good because the way they have to do their work does not involve engaging with objects. This means that they are not enriched by their encounter with objects. Because of the lack of true work, the subject shrivels up and in his spare time he is nothing.

h/t Brian Leiter.

by Henry Farrell on November 3, 2011

Scott’s new “article”:http://www.insidehighered.com/views/2011/11/02/essay-librarians-occupy-movement at _IHE_ provides some interesting follow up information on the role of librarians in _OWS_ (and their historical antecedents).

bq. Steven Syrek, a graduate student in English at Rutgers University, has been working at the OWS library since about the third week of the demonstration. “People talk about this movement like it’s a ragtag bunch of hippies,” he told me when we spoke by phone, “but the work we do is extremely well-organized.” The central commitment, Syrek says, is to create “a genuine clearinghouse for books and information.” Volunteers have adopted a slogan summing up what the library brings to the movement: “Literacy, Legitimacy, and Moral Authority.”

bq. … But the libraries at the anti-Wall Street protests are not quite as novel as they first appear. They have a tradition going back the better part of two centuries. In a recent article, Matthew Battles, the author of Libraries: An Unquiet History (Norton, 2004), noted the similarity to the reading rooms that served the egalitarian Chartist movement in Britain. … points out that libraries emerged as part of the sit-down strikes that unionized the American auto industry in the 1930s. …

bq. So the OWS library and its spin-offs have a venerable ancestry. But what distinguishes them is that the collections are drawing in people with a deep background in library work – who, aside from their feelings about the economic situation itself, are sometimes frustrated by the state of their profession. … The issue here isn’t just the impact on the librarians’ own standard of living. Their professional ethos is defined by a commitment to making information available to the public. They are very serious about that obligation, or at least the good ones are, and they are having a hard time meeting it. If knowledge is power, then expensive databases, fewer books, and shorter library hours add up to growing intellectual disenfranchisement. … joining the occupation movement is a way for librarians “to begin taking power back,” Henk says, “the power to create collections and to define what a library is for.” It is, in effect, a battle for the soul of the library as an institution.

by Ingrid Robeyns on October 26, 2011

Over the last two years, I’ve given a couple of interviews to journalists, mainly about my research on issues of justice, or, sometimes, about my reasons to swap economics for political philosophy, and my views on those fields. But now those same journalists are calling or e-mailing me back with questions where I really don’t have any expertise at all. They could ask any of us, really. Here’s one, that I thought is interesting to share.

A religiously-inspired progressively-leaning magazine is starting a new series, namely asking people which book “provides support, or is a book to which one often returns”. And the answer cannot be the Bible. I actually don’t think I can answer this question. Most fiction, with very few exceptions, I’ve only read once. Non-fiction I read is either informative (like King Leopold’s Ghost, or Joris Luyendijk’s book on the Middle East), or else it is scholarly, but then I don’t think I see it as providing (moral) support or as an inspirational book. Of course, I’ve opened A Theory of Justice or Inequality Reexamined or Justice, Gender and the Family many times, but that’s mostly because I want to return to the arguments to examine them. Moreover, most of the (non-professional) reading I do is on blogs and the internet.

So what, if anything, could be similar to an atheist as the Bible is to a Christian? I really don’t know. But if I’m forced to give an answer, I would say: I prefer talking to people over reading books if I need (moral) guidance or support, and if I need inspiration or some distance and non-analytical reflection, I turn to poetry. I still have, ripped from a student’s magazine when I was studying in Göttingen in 1994/5, a page with a Poem written by Nazim Hikmet, translated in German – a poem to which I have returned many, many times:

Leben

einzeln und frei

wie ein Baum

und brüderlich

wie ein Wald

ist unsere Sehnsucht.

So give me poetry and people if I need inspiration or support. And you?

by Henry Farrell on October 10, 2011

So I’m informed that the _Occupy Wall Street_ movement has a pretty good library, and that it’s possible to donate books to it by sending them to:

The UPS Store

Re: Occupy Wall Street

Attn: The People’s Library

118A Fulton St. #205

New York, NY 10038

I’ve just sent them a copy of “Pierson/Hacker’s Winner Take All Politics“:https://crookedtimber.org/2010/09/15/review-jacob-hacker-and-paul-pierson-winner-take-all-politics/, which I think is both very readable (important if you are trying to get through it under not exceptionally wonderful reading conditions) and terrific on the substance of why we are in a 99%/1% society. I encourage CT readers (a) to send books that they think might be good reading for OWS people, and (b) to leave comments saying which books they think should be in the library, and why. You certainly do not have to do (a) to write (b), but if you are in a position to send a book, it would obviously be nice (and a good, albeit small gesture of solidarity – I may be atypical, but if I were sitting and camping out, I’d really like to have something good to read during the duller moments). Also – these don’t have to be weighty tomes of policy analysis or whatever – you may reasonably think that the people occupying Wall Street don’t need to read those books, or that they may want lighter and livelier stuff.

books, mainly for the combination of complex plotting, interesting delightful characters, and many very comedic moments. The first 5 or 6 are fairly straightforward whodunnit/police procedurals (with the exception of Deadheads

which defies one of the central conventions of the whodunnit), but one reason Hill became so good is that he experimented, frequently, in the novels, with style, format, and, increasingly often, convention. Most of his non-series books (his other series about Joe Sixmith, a black detective in Luton, was much more relentlessly humorous) were written in the 70s and early 80’s, often under pseudonyms (he has published under at least 4 names, maybe more), before he got to be really good. But the last two were brilliant, especially The Woodcutter

, which is riveting, as good as any of the Dalziel/Pascoe books.

seems to confirm. So, one more to come.