by John Q on July 18, 2020

As with most really neat sayings, the original (with billions, instead of trillions) is misattributed, in this case to the late Senator Everett Dirksen, a conservative Republican who nonetheless helped to write the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The saying can be traced back to an unsigned New York Times article in 1938, which said ““Well, now, about this new budget. It’s a billion here and a billion there, and by and by it begins to mount up into money”. This in turn improved on earlier versions going back at least to 1917

US GDP today (Over $20 trillion) is around 250 times as high, in dollar terms, as it was in 1938, so replacing billions with trillions isn’t much of a stretch.

With that in mind, what should we think about the $2.4 trillion pandemic relief package, and the likelihood of huge demands for public expenditure stretching well into the future? And how much of this analysis is applicable to the world as a whole, where large scale government responses have been the norm rather than the exception.

[click to continue…]

by John Q on July 9, 2020

The title of my book-in-progress, The Economic Consequences of the Pandemic is obviously meant as an allusion to Keynes’ The Economic Consequences of the Peace, and one of the central messages will be the need to resist austerity policies of the kind Keynes criticised in his major work, The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money. That title, in turn was an allusion to Einstein*, and the Special and General theories of Relativity.

[click to continue…]

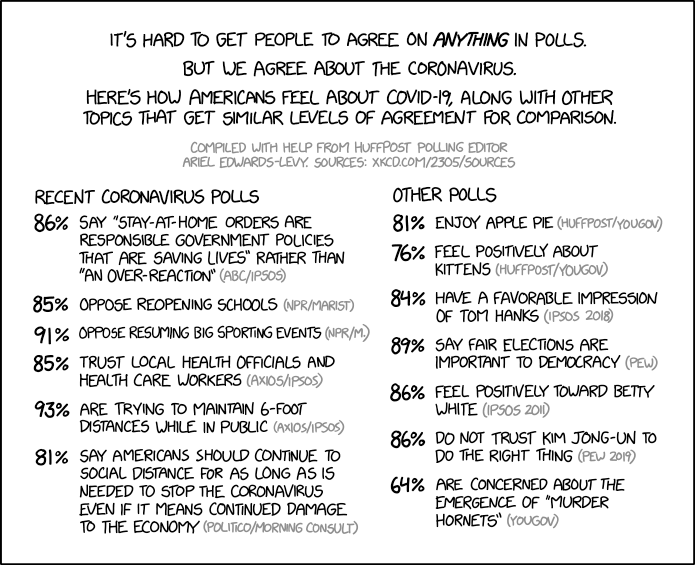

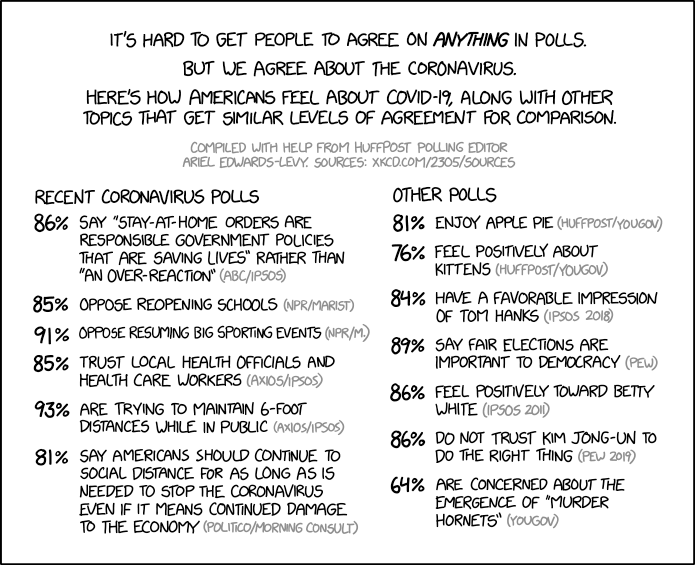

by Henry Farrell on May 12, 2020

An addendum to my earlier post, to explain more directly why I am skeptical of the argument that public choice is a useful lens to understand the politics of the public during coronavirus. Shorter version: if the “public” is indeed some kind of equilibrium, then the underlying game is unlikely to be the kind of game that public choice scholars like to model. [click to continue…]

by Henry Farrell on May 4, 2020

The website Five Books did an interview with me on the five best books on the politics of information. It was an interesting experience. Picking the best five books means that you have to go back and re-read them, and figure out how they fit together.

What I decided to do was to take this essay by Ludwig Siegele in the Economist’s Christmas issue, and start from the question: If you wanted people to build out from that essay, what books would you have them read? The essay is influenced by Francis Spufford’s Red Plenty, and the Crooked Timber seminar that followed from it (in particular: Cosma’s essay): what it sets out to do is to ask whether the socialist calculation debate helps us to understand current fights about democracy, autocracy, markets and machine learning. Like Ludwig, I believe that it does: “Comrades! Let’s Optimize” is an excellent starting point for understanding how people in Silicon Valley today think about the transformative power of software. I also think that Red Plenty is an excellent starting point for thinking about these questions because it is a novel rather than a tract. As Francis said in his reply, writing fiction gives you access to negative capability: rather than stating an argument or a principle, you can have a multiplicity of voices and experiences, providing a kaleidoscopic rather than a synoptic understanding of the problem. When it’s a complex problem, that’s helpful.

A certain kind of autobiography can pull off a similar trick: hence the structure of the interview is that it starts off with Red Plenty and finishes with Anna Wiener’s wonderful account of living in Silicon Valley, sandwiching the social science between these two more complicated narratives. It’s a long interview (about 10,000 words!) and has nothing about coronavirus (it was conducted in February), but I think it worked out well. Read if interested; ignore if not.

by Henry Farrell on April 17, 2020

was once a demand made by Kieran on Chatroulette (remember Chatroulette?), but is now becoming an amateur spectator sport, as people scope out other people’s bookshelves on Zoom, and some of those other people in turn likely artfully arrange their books so as to present the best possible image of their serious or not-so-serious intellectual life. The Twitter commentary on this Pete Buttigeig bookshelf has already started.

For me, the interesting bit was not the volumes of Dragonball, or the Piketty in and of itself, so much as the way in which Piketty and a few issues of N+1 bracketted a copy of Juan Zarate’s decidedly non-leftwing book on US financial power, Treasury’s War. Perhaps the message that was intended to be conveyed was of how a leftwing attack on the power of capital and global inequality might be organized around the awesome power of the US over the global financial system. Or, perhaps, that’s just me.

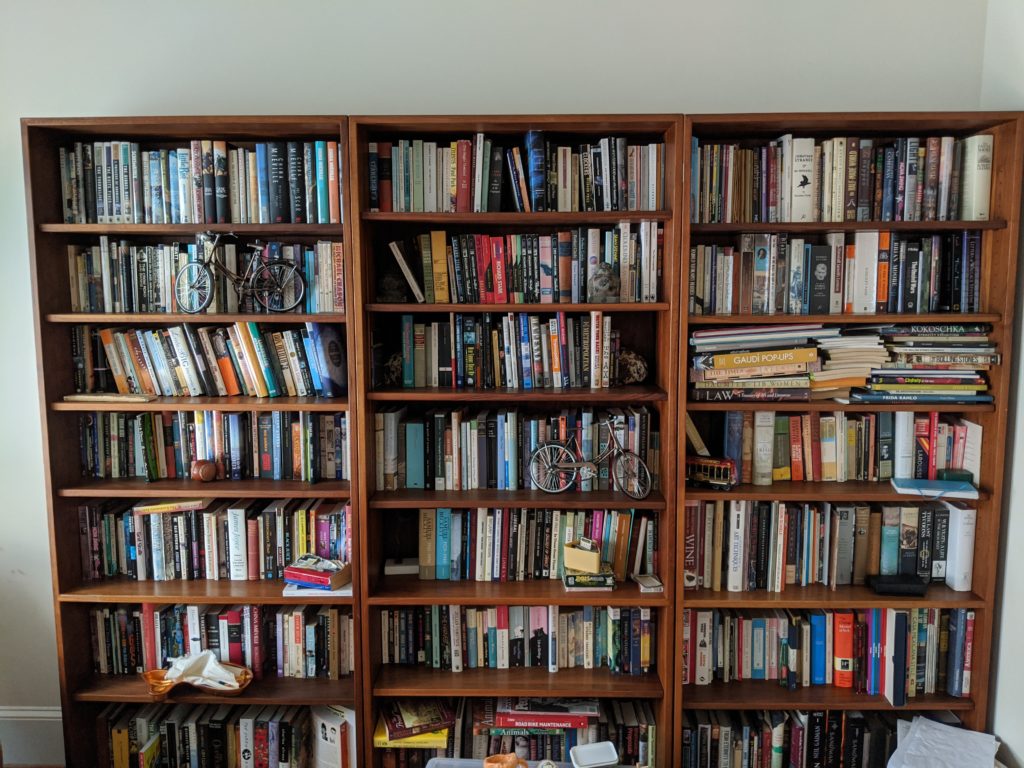

Either which way, one way to keep some of us occupied is to scope out each other’s bookshelves. Here’s mine (as the disorder suggests, I haven’t artfully rearranged it at all, though I have chosen the bookshelf in our house with the greatest concentration of intellectually ‘serious’ books).

Feel free to snoop, and to disparage my taste. Feel just as free to include links to photos of your own bookshelves in comments (it looks as though img src is disabled in CT comments, but links should work fine).

by Henry Farrell on April 6, 2020

Attention conservation notice: below the fold is a lengthy and spoiler-filled response to William Gibson’s new book Agency. Probably best not to read unless you’ve already finished Agency, or have no intention of reading it and want to get some sense as to what the book is about. In either case, you’re likely better off reading Mike Harrison’s Guardian review, which covers much the same ground as below, but with more subtlety and fewer spoilers.

[click to continue…]

by Chris Bertram on February 24, 2020

Sometimes you are reading a novel and it is so extraordinary that you think, is this the best thing I have ever read? For me, that feeling probably comes on about once a year, so there are quite a lot of books that have evoked it. Still, that they do says something, and the latest to have sparked it is Anna Burns’s Milkman, the Booker Prize winner from 2018.

Milkman is, all at once, a tremendous linguistic performance, a triumph of phenomenology, am insightful account of sexual harrassment, a meditation on gossip and what it can do, a picture of the absurdities of enforced communitarian conformity, and a clear-eyed portrayal of what it is to live under the occupation of a foreign army and the domination of the necessary resisters to that army who are, at the same time, friends and family, sometime idealists but sometimes gangsters, bullies and killers.

Anna Burns’s sentences, the stream of consciousness of her 18-year-old narrator, loop back on themselves with further thoughts and reconsiderations. The voice is a combination of personal idiosyncracy and northern Irish English, i.e. comprehensible to speakers of other versions of English but sometimes odd or disconcerting. You can’t skim and get the plot. You have to hold on, read each sentence, and sometime start it again.

[click to continue…]

by Chris Bertram on February 19, 2020

A brief plug for an important new (and affordable) book: every home should have one! David Owen has long been know for his thoughtful contribution to philosophical debates around migration, and now he has published a brilliant short book, [*What Do We Owe to Refugees?*](https://politybooks.com/bookdetail/?isbn=9781509539734&subject_id=2) in the same excellent *Political Theory Today* series from Polity that my own book appears in. David’s book is highly readable and gives a solid introduction to the main controversy that runs through modern debates on refugeehood, namely, whether we should adopt a “humanitarian” or a “political” conception of refugees and what we owe to them.

A humanitarian conception of refugees focuses attention on them as needy persons forcibly displaced through no fault of their own. They may be fleeing persecution, or war, or natural disaster or environmental collapse, and the duties that we have to them flow from our common humanity. It is their neediness and not the specific cause of their neediness that is the most important factor. A political conception, by contrast, sees refugees as victims of a special wrong, the denial of political status, of effective citizenship through persecution by the very state whose obligation it is to include them as citizens and to guarantee and respect their rights. Refugeehood as conceived of by the political conception is an internationally-recognized political substitute for the membership that has been unjustly denied by a person’s persecutors.

[click to continue…]

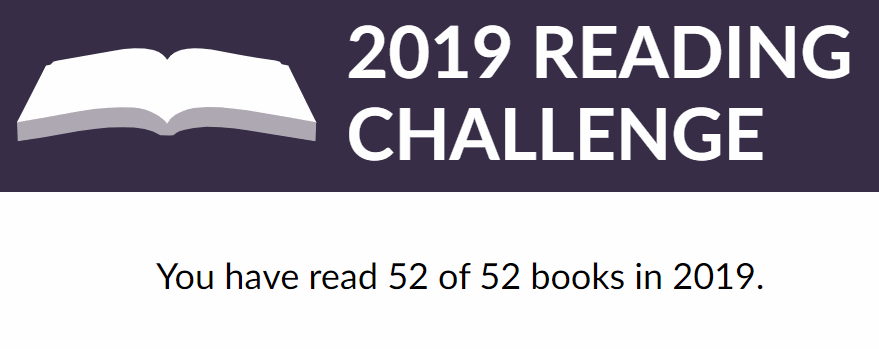

by Eszter Hargittai on December 22, 2019

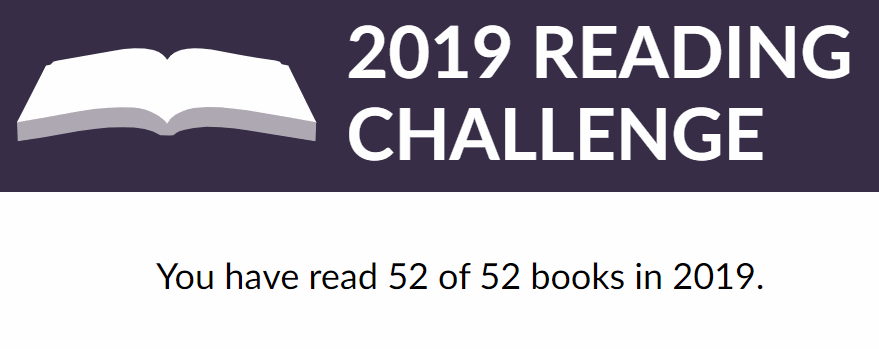

I almost never make New Year’s resolutions, but I did in January 2019: read a book a week for 2019. This weekend I finished my reading challenge with Jose Antonio Vargas’s

Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen (I recommend it!). While book reading has always been a part of my life, as an academic who reads a lot for work (mostly in journal article form), book reading for fun hasn’t always fit in. I wanted it to be more prominent in my everydays and I’m glad that I achieved that. I only counted books that I read from cover to cover, there are certainly others I browsed and read parts of, but they didn’t count for my challenge. I included very different genres as my interests are eclectic, but the most prominent was memoirs and biographies (I am not a huge fiction fan so there were only a few of those on my list). Here, I want to share my top three overall favorites; another three that you are unlikely to have heard of, but that I found very much worth reading; three that were the most disappointing; and three art books I enjoyed. While I have an insane “would like to read” list already, I very much welcome your recommendations for 2020 (when I’ll even have a semester of sabbatical in the Fall so I definitely plan to get at least as much reading in).

Overall top 3

Madame Fourcade’s Secret War by Lynne Olson – A fascinating story told in an incredibly engaging manner about the young woman, Marie-Madeleine Fourcade, who led the largest French resistance network during WWII. This book is now among my all-time favorite books.

Educated by Tara Westover – You’ve probably heard of this book, it’s been very popular, and deservedly so. The author was raised in a very religious family in Idaho that did not believe in public education. The family dynamics are insane and intense. It’s often a tougher read than I expected due to the difficulties she faced beyond what you may imagine going in.

Evicted by Matthew Desmond – Based on the author’s sociology dissertation, this is an important story about major housing challenges in poor urban America. The research is first-rate, the writing excellent. (If I want to get academic, I’ll note my one critique: a lack of discussion of what role digital media may have played in people’s lives. The absense of this in the book is jarring to someone like me who studies the use of information technologies. Jeff Lane’s the Digital Street addresses that angle as does the work of Will Marler, a graduate student at Northwestern whose dissertation I am advising, but not specifically about housing challenges. I would have liked to see some of this in Evicted.) An refreshing aspect of the book is that it offers concrete policy recommendations at the end.

Top 3 you probably haven’t heard of

[click to continue…]

by John Q on October 9, 2019

Another review of Economics in Two Lessons has come out. It’s by David Henderson and appears in Regulation, published by the Cato Institute (link to PDF). There’s a blog post with extracts here.

Unsurprisingly, given the source, it’s mainly critical of the analysis, but still has some kind words about the book. This para gives the flavour

Quiggin is a good writer who lays out much of the economics well. His analysis of rent control and price controls in general is a thing of beauty. Along the way, though, he makes small and big mistakes. He also shows by omission that the book, to be complete, badly needs a third lesson, on why government works so badly even when it intervenes in cases where markets work badly.

[click to continue…]

by Henry Farrell on August 14, 2019

Caragh Lake, the epicenter of the future

[Caragh Lake: the epicenter of the future]

In 1959 the famous British astronomer Fred Hoyle published his novel, Ossian’s Ride. It was the wildest science fiction, depicting a future Ireland miraculously transformed into a technological superpower. Vast highways crisscrossed the Irish countryside. The discovery of cheap contraception (manufactured from turf) broke the control of the Catholic church. A shining new city, organized around the principles of scientific discovery, was constructed on the shores of Caragh Lake in County Kerry. Britain was left on the sidelines, wondering what had happened.

[click to continue…]

by Scott Page on August 14, 2019

Freeman testified at trial that Abrahams was trying to stop him and Willingham from fighting, and that she hit Willingham in the face. Willingham, Freeman testified, then raised his hand as if he was going to hit Abrahams, but then lowered it to his waist, which prompted Freeman to believe he had a gun. Freeman shot Willingham three times, according to police.

-Detroit Free Press June 20, 2019

America is very good at some things and very bad at others. We produce a steady flow of scientific, cultural, and engineering successes– in the past five years we can lay claim to a drug that cures hepatitis C, Hamilton: The Musical, and self-driving cars. And yet, we perform just this side of miserable at addressing core social and economic challenges. We are among the world’s leaders in income inequality, obesity rates, drug overdose deaths, and per capita greenhouse gas emissions.  And, we rank first, that is worst, in the proportion of citizens in jail at about seven people per thousand. Even more troubling, blacks are six times as likely as whites to be behind bars. [click to continue…]

by Henry Farrell on July 10, 2019

[being a review of Alex Hertel-Fernandez’ State Capture: How Conservative Activists, Big Businesses, and Wealthy Donors Reshaped the American States ,“ and the Nation – cross posted from HistPhil]

A couple of months ago, Yvonne Wingett Sanchez and Rob O’Dell wrote a long journalistic article on the influence of ALEC, the right-wing American Legislative Exchange Council, on legislation in U.S. states. ALEC has had enormous influence on state legislatures by providing model bills and courting lawmakers. O’Dell suggested on Twitter that this marked “the first time anyone has been able to concretely say how much legislation is written by special interests.” This … wasn’t exactly accurate. Columbia University political science professor Alex Hertel-Fernandez, who is briefly quoted in the piece, had recently published his book State Capture: How Conservative Activists, Big Businesses, and Wealthy Donors Reshaped the American States,” and the Nation, which applied similar data to similar effect.

It was a real pity that the book didn’t get the credit it deserved, and not just for the obvious reasons. While the article was good, it focused on describing the outcomes of ALEC’s influence. The book does this but much more besides. It provides a detailed and sophisticated understanding of how ALEC has come to have influence throughout the U.S., how it is integrated with other conservative organizations, and how progressives might best respond to its success.

It’s a great book – crisply written, straightforward, and enormously important. It is energetic and useful because it is based on real and careful research. Hertel-Fernandezâ’s politics are obviously and frankly on the left. But even though his analysis starts from his political goals, it isn’t blinded by them so as to distort the facts.

[click to continue…]

by John Q on June 29, 2019

I’ve been busy for the last week doing events for Economics in Two Lessons, so I didn’t have time to take part in the discussion arising from Harry’s post on alternatives to Sanders’ proposal to wipe out college debt.

In one way, that’s a pity because the key point of the book is the idea of opportunity cost – the true cost of anything, for us as individuals, and for society as a whole, is what you must give up to get it. More precisely, it’s the best alternative available to us.

Harry’s post was all about opportunity cost – what would be the best use of $1.6 trillion in public funds. However, the discussion was inevitably enmeshed in the complexities and inequities of US education, while comments making broader arguments about opportunity cost reasoning weren’t discussed in detail.

One of those broader arguments is the idea that, thanks to Modern Monetary Theory, there’s no need to worry about such questions. In the “chartalist” reasoning underlyng MMT, the fact that governments can issue their own sovereign currency means that there is no need to “finance” public spending by taxation; rather taxation is a tool used to manage aggregate demand so as to keep the economy fully employed but not at a point where excess demand creates inflation. That (essentially correct) position can easily slide into the (only subtly different, but radically mistaken) view that governments can spend money on anything they like with no need for any increases in taxes or cuts in other spending.

As I will argue over the fold, a correct version of MMT makes no such claim. Unfortunately, while avoiding the error themselves, a lot of MMT theorists have not shown much willingness to set their more naive followers straight.

[click to continue…]

by John Q on April 27, 2019

April 23 was the official release day for Economics in Two Lessons. The book is now out in Australia as well Economics In Two Lessonsis now available in Australia from Footprint books.

It’s nearly eight years since I started work on the book. I think it’s been worth the wait. The painful process has produced something better than I originally planned, with plenty of help from commenters here and elsewhere.

According to Amazon, the book is often bought along with Crashed, by Adam Tooze, which is great company to be in.

[Begin plug] If you’ve read and liked the book as it appeared here, this would be a great time to contribute a quick review [End plug]