Wait, why do we have actually have The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel ? If you have ten minutes to spare, Philip Mirowski will give us part of the answer, and tell us about his research project investigating this issue.

From the category archives:

Economics/Finance

Catherine Hill, President of Vassar, at the Washington Post explaining the rapid increase in tuition at elite colleges:

Increased access to higher education would help moderate the expansion in income inequality over time. Yet the increasing inequality itself presents obstacles to achieving this goal.

Real income growth that skews toward higher-income families creates challenges for higher education. The highest-income families are able and willing to pay the full sticker price. Schools compete for these students, supplying the services that they desire, which pushes up costs. Restraining tuition and spending in the face of this demand is difficult. These students will go to the schools that meet their demands.

Hence the proliferation of climbing walls and luxury dorms at selective and highly selective colleges (one college president told me that the climbing wall is a highlight of the college tour at both the private colleges he has led). Highly selective education is a positional good, and wealthy families have become enormously wealthier over the past 30 years and have been having fewer children: what are they going to do with all that money? Compete with each other to get their children into the best possible position, thus bidding up the price of highly elite colleges, making it unaffordable for others. In fact, elite colleges respond by using some of the revenues from those who cheerfully pay full price to subsidize students whose families cannot:

At the same time, many schools are committed to recruiting and educating a socioeconomically diverse student body. At private, nonprofit institutions, this commitment has been supported through financial aid policies.

Telling elite schools to keep down tuition doesn’t help:

Ironically, some of the proposed “solutions” to make higher-education finances sustainable would exacerbate future income inequality rather than address the trends that are creating financial challenges for institutions.

For example, in his 2012 State of the Union address, Obama called on colleges to slow down tuition increases and threatened to reduce public support. “If you can’t stop tuition from going up, the funding you get from taxpayers will go down,” he said. But slow tuition growth not tied to offsetting expenditure savings can result in reductions to financial aid. This is playing out in the private, nonprofit sector. Lower tuition combined with lower financial aid benefits higher-income students and hurts lower-income students.

Of course, public institutions, which are the main resort for lower income families, are different. They are the main resort partly because they have traditionally had a low-tuition, low-aid, model, and I cannot tell you how many students I have talked to who were deterred from applying to more selective private schools by the sticker price, applied only to Madison because it had low tuition, but who, I know, would be in much less debt than they are if they had applied to and attended the more selective, elite, private schools that they spurned because of the sticker price (which they would not have had to pay). Anyway, well worth reading the whole piece.

Alex Pareene at Salon points to a bunch of evidence showing, in essence, that the rich look out for themselves and their kids, and no one else, then to a piece by Andrew Ross Sorkin defending nepotism in the US, and by extension in China. There was a time, not so long ago, when Asia’s reliance on guanxi and similar networking practices was denounced as ‘crony capitalism’, to be contrasted with the pure and hard-edged version to be found in the US. This was supposed to explain the vulnerability of Asian economies to the crisis of 1997, and the stability of the US, then well into the Great Moderation.

A few years later, in the very early days of blogging, I wrote a post pointing out that the eagerness of financial sector workers to congregate in the same physical location, even though their work was supposed to be based on objective evaluation of data transmitted by computer, was pretty good evidence that the “global city” phenomenon, much in vogue at the time, was just guanxi writ large.

I turned that into a magazine article at Next American City (now Next City, whose web site seems to have lost it). Then I wrote a longer and more academic version and submitted it a lot of journals in economic geography, urban geography and so on, none of whom were interested. I think it stands up well in retrospect (much more so than most of the ‘global city’ literature, at any rate), but of course I’m biased.

At any rate, at least now everyone, and not least a defender and beneficiary of the system like Sorkin, is comfortable with the notion that capitalism is a rigged game, in which the ability to fix the next round is part of the prize for winning this one.

Update/clarification I’ve implicitly taken the efficient markets hypothesis as a benchmark, and assumed that features of the financial sector (for example, physical colocation) that can’t be explained by EMH are likely indicators of cronyism. It’s possible to take the view that the financial sector does things that are inconsistent with EMH, but nevertheless socially beneficial. An obvious example is the kind of opaque, over-the-counter derivatives that Dodd-Frank has tried to ban, and that the finance sector is lobbying hard to protect: it seems clear that doing these kinds of deals would benefit from face-to-face contact. So, if such deals are, in aggregate, socially beneficial, my argument fails – the converse also holds.

Paul Krugman’s recent columns, responding in various ways to JM Keynes, Michal Kalecki and Mike Konczal have made interesting reading, signalling a marked shift to the left both on economic theory and on issues of political economy.[^1] Among the critical points he has made

* Endorsement of Kalecki’s argument (which he got via Konczal) that “hatred for Keynesian economics has less to do with the notion that unemployment isn’t a proper subject of policy than about the notion of shifting power over the economy’s destiny away from big business and toward elected officials.”

* Rejection of the Hicks-Samuelson synthesis of Keynesian macroeconomics and neoclassical microeconomics and advocacy of (at a minimum) comprehensive financial controls

* Abandonment of the idea that the economics profession is engaged in honest intellectual debate, in favor of the conclusion that the rightwing of the profession, including leading economists, is characterized by denialism and bad faith. As he says, while many economists would like to believe otherwise ” you go to economic debates with the profession you have, not the profession you want.”

In the controversy over who should replace Ben Bernanke as Chairman of the US Fed, a fair bit is being made of the fact that Larry Summers is (to put it politely) a jerk. Without denying this, I’d like point out that, when it really mattered, Summers was thoroughly outjerked by the genuine article, Rahm Emanuel.

The occasion was the decision on a stimulus package needed immediately after Obama’s inauguration. Emanuel’s brilliant strategy was to go for as small a stimulus as possible, declare victory on the economic front, then turn to the main game of cutting a deal with the Republicans on health care reform. We all know how that turned out, [^1] and anyone who recalled the Great Depression could easily have foreseen it. I can recall how stunned I was that Obama failed to take the obvious opportunity to nail Bush and the Repubs for the crisis, and switch to a single-minded focus on economic recovery.

The Keynesian analysis done inside the White House by Christina Romer and outside by Paul Krugman showed that what was needed was a stimulus of at least $1.7 trillion. Based on his subsequent commentary, it’s clear the Summers understood and agreed with this. If he had lived up to his reputation, Summers would have pushed this through the White House by demonstrating, beyond any doubt, that Emanuel was the kind of fool he is famed for not suffering gladly. Instead, he first made Romer reduce the estimate to $1.2 trillion, then dropped it from his brief without telling her, giving Obama a range from $600 billion to $800 billion.

Summers is great at saying the unsayable when it comes to things like shipping toxic waste to poor countries or making baseless speculations about genetics and gender. But when it really mattered, he couldn’t come up to scratch.

Note: Out of laziness, I omitted the link to the piece by Noam Scheiber, on which I relied. I’ve added it now.

[^1]: Fans of 11-dimensional chess might want to make the case that Obama deliberately threw the 2010 election to the Tea Party, foreseeing that the resulting hubris would drive the Repubs mad, and therefore lead to their ultimate destruction. But I can’t impute such subtlety to Emanuel.

[Monsters University](http://monstersuniversity.com/edu/), the prequel to [Monsters, Inc](http://disney.go.com/monstersinc/index.html), opened this weekend. I brought the kids to see it. As a faculty member at what is generally thought of as America’s most [monstrous university](http://duke.edu), I was naturally interested in seeing how higher education worked in Monstropolis. What sort of pedagogical techniques are in vogue there? Is the flipped classroom all the rage? What’s the structure of the curriculum? These are natural questions to ask of a children’s movie about imaginary creatures. Do I have to say there will be spoilers? Of course there will be spoilers. (But really, if you are the sort of person who would be genuinely upset by having someone reveal a few plot points in *Monsters University*, I am not sure I have any sympathy for you at all.) As it turned out, while my initial reactions focused on aspects of everyday campus life at MU, my considered reaction is that, as an institution, Monsters University is doomed.

Remember when Robert Nozick wrote in Anarchy State and Utopia that income taxation is akin to forced labour? Well it turns out that that is far far worse than that. Taxing the 1 per cent would be like the state forcibly ripping out their spare internal organs! At least that’s what Gregory Mankiw thinks. His paper, forthcoming in the Journal of Economic Perspectives also includes a thinly-disguised rehash of the Wilt Chamberlain parable, but no proper acknowledgement to Nozick (suprising that the referees or editors at JEP didn’t make this point).

“All successful revolutions are the kicking in of a rotten door.” – J. K. Galbraith

Kickstarter is glorious insofar as it is a well-earned kick to a rotten door.

That’s why a lot of people are griped about Zach Braff funding his Garden City sequel this way.

The idea – and it’s a great one – is that Kickstarter allows filmmakers who otherwise would have NO access to Hollywood and NO access to serious investors to scrounge up enough money to make their movies. Zach Braff has contacts. Zach Braff has a name. Zach Braff has a track record. Zach Braff has residuals. He can get in a room with money people. He is represented by a major talent agency. But the poor schmoe in Mobile, Alabama or Walla Walla, Washington has none of those advantages.

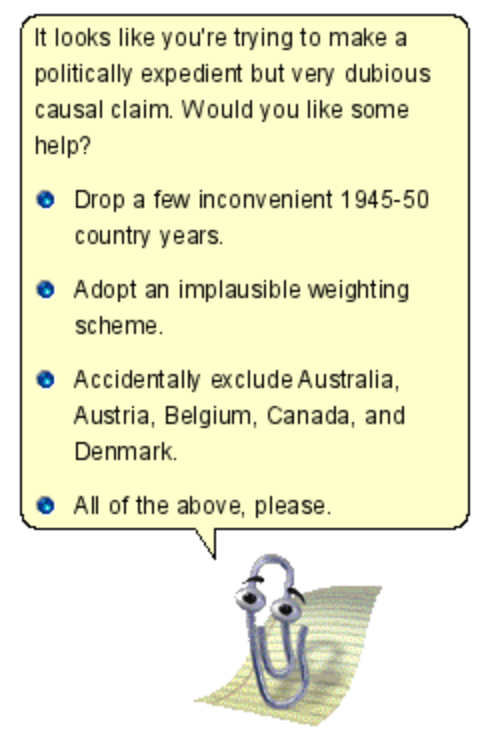

“Paul Krugman”:http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/26/grasping-at-straw-men/ on the “latest Reinhart-Rogoff self-defense”:http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/26/opinion/debt-growth-and-the-austerity-debate.html?hp&_r=0

bq. OK, Reinhart and Rogoff have said their piece. I’d say that they’re still trying to have it both ways, on two fronts. They deny asserting that the debt-growth relationship is causal, but keep making statements that insinuate that it is. And they deny having been strong austerity advocates – but they were happy to bask in the celebrity that came with their adoption as austerian mascots, and never to my knowledge spoke out to condemn all the “eek! 90 percent!” rhetoric that was used to justify sharp austerity right now.

Maybe worth noting that this is a variant of John Holbo’s “Two-Step of Terrific Triviality”:https://crookedtimber.org/2007/04/11/when-i-hear-the-word-culture-aw-hell-with-it/

bq. To put it another way, Goldberg is making a standard rhetorical move which has no accepted name, but which really needs one. I call it ‘the two-step of terrific triviality’. Say something that is ambiguous between something so strong it is absurd and so weak that it would be absurd even to mention it. When attacked, hop from foot to foot as necessary, keeping a serious expression on your face. With luck, you will be able to generate the mistaken impression that you haven’t been knocked flat, by rights. As a result, the thing that you said which was absurdly strong will appear to have some obscure grain of truth in it. Even though you have provided no reason to think so.

The Boston Review symposium I pointed to last year on James Heckman’s “Promoting Social Mobility” is now out in book form as Giving Kids a Fair Chance. Its all still on the web, at least right now, but the book is cute and inexpensive. I’m curious what other people’s experience is, but I find that when I assign a book in class it gets read by more students, and more carefully, than if I assign something from the web; so I am planning to use it alongside Unequal Childhoods

with my freshman class in the fall.

Over at the National Interest, I have a piece arguing that Bitcoin is a more perfect example of a bubble, and therefore a more perfect refutation of the Efficient Markets Hypothesis, than anything seen previously. Key quote

It beats the classic historical example, produced during the 18th century South Sea Bubble of “a company for carrying out an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is.” After all, the promoter of this enterprise might, in principle, have had a genuine secret plan. Bitcoin also outmatches Ponzi schemes, which rely on the claim that the issuer is undertaking some kind of financial arbitrage (the original Ponzi scheme was supposed to involve postal orders). The closest parallel is the fictitious dotcom company imagined in Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury, whose only product was its own stock.

[My reflections on Britain since the Seventies](https://crookedtimber.org/2013/04/10/britain-since-the-seventies-impressionistic-thoughts/) the other day partly depended on a narrative about social mobility that has become part of the political culture, repeated by the likes of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown and recycled by journalists and commentators. In brief: it is the conventional wisdom. That story is basically that Britain enjoyed a lot of social mobility between the Second World War and the 1970s, but that this has closed down since. It is an orthodoxy that can, and has, been put in the service of both left and right. The left can claim that neoliberalism results in a less fluid society than the postwar welfare state did; the right can go on about how the left, by abolishing the grammar schools, have locked the talented poor out of the elite. And New Labour, with its mantra of education, education, education, argued that more spending on schools and wider access to higher education could unfreeze the barriers to mobility. (Senior university administrators, hungry for funds, have also been keen to promote the notion that higher education is a social solvent.)

[click to continue…]

The 1970s have been in my mind over the past few days, not only for the obvious reason, but also because I visited the Glam exhibition at Tate Liverpool last weekend. Not only were the seventies the final decade of an electrical-chemical epoch that stretched back to the late nineteenth-century, they were also the time when the sexual and political experimentation of the 1960s and a sense of being part of a cosmopolitan world order became something for the masses, for the working class, and when the old social order started to dissolve. In the experience of many people, the sixties happened in the seventies, as it were.

But my main thoughts, concerning Britain at any rate, have been about social division, and about some oddly paradoxical features of British life before Thatcher. There’s a very real sense in which postwar British society was very sharply divided. On the one hand, it was possible to be born in an NHS hospital, to grow up on a council estate, to attend a state school, to work in a nationalised industry and, eventually (people hoped), to retire on a decent state pension, living entirely within a socialised system co-managed by the state and a powerful Labour movement. On the other, there were people who shared the experience of the NHS but with whom the commonality stopped there: they were privately educated, lived in an owner-occupied house and worked in the private sector. These were two alternate moral universes governed by their own sets of assumptions and inhabited by people with quite different outlooks. Both were powerful disciplinary orders. The working class society had one set of assumptions – welfarist, communitarian, but strongly gendered and somewhat intolerant of sexual “deviance”; middle-class society had another, expressed at public (that is, private) schools through institutions like compulsory Anglican chapel. Inside the private-sector world, at least, there was a powerful sense of resentment towards Labour, expressed in slogans about “managers right to manage” and so on that later found expression in some of the sadism of the Thatcher era towards the working-class communities that were being destroyed. Present too, at least in the more paranoid ramblings of those who contemplated coups against Labour, was the idea that that the parallel socialised order represented a kind of incipient Soviet alternative-in-waiting that might one day swallow them up.

[click to continue…]

There’s already plenty of commentary, here and elsewhere on Margaret Thatcher. Rather than add to it, I’d like to compare the situation when she assumed the leadership of the Conservative Party with the one we face now. As Corey points out in his post

In the early 1970s, Tory MP Edward Heath was facing high unemployment and massive trade union unrest. Despite having come into office on a vague promise to contest some elements of the postwar Keynesian consensus, he was forced to reverse course. Instead of austerity, he pumped money into the economy via increases in pensions and benefits and tax cuts. That shift in policy came to be called the “U-Turn.”

Crucially, Heath was defeated mainly as a result of strikes by the coal miners union.[1]

From the viewpoint of conservatives, the postwar Keynesian/social democratic consensus had failed, producing chronic stagflation, but the system could not be changed because of the entrenched power of the trade unions, and particularly the National Union of Miners. In addition, the established structures of the state such as the civil service and the BBC were saturated with social democratic thinking.[2]

Thatcher reversed all of these conditions, smashing the miners union and greatly weakening the movement in general, and promoting and implementing market liberal ideology as a response to the (actual and perceived) failures of social democracy. Her policies accelerated the decline of the manufacturing sector, and its replacement by an economy reliant mainly on the financial sector, exploiting the international role of the City of London.

Our current situation seems to me to be a mirror image of 1975. Once again the dominant ideology has led to economic crisis, but attempts to break away from it (such as the initial swing to Keynesian stimulus) have been rolled back in favour of even more vigorous pursuit of the policies that created the crisis. The financial sector now plays the role of the miners’ union (as seen in Thatcherite mythology) as the unelected and unaccountable power that prevents any positive change.

Is our own version of Thatcher waiting somewhere in the wings to take on the banks and mount an ideological counter-offensive against market liberalism? If so, it’s not obvious to me, but then, there wasn’t much in Thatcher’s pre-1975 career that would have led anyone to predict the character of her Prime Ministership.

fn1. I was too far from the scene to be able to assess the rights and wrongs of these strikes or the failed strike of the early 1980. It’s obvious that the final outcome was disastrous both for coal miners and for British workers in general, but not that there was a better alternative on offer at the time.

fn2. The popular series, Yes Minister, was essentially a full-length elaboration of this belief, informed by public choice theory