As Henry mentioned this morning, I’ll be doing a series of guest posts at Crooked Timber this week. I’m grateful for the invitation. My posts will be on strategies for reducing income inequality in the United States.

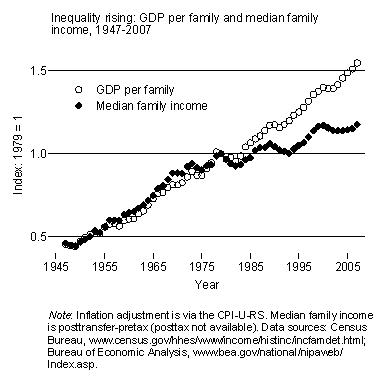

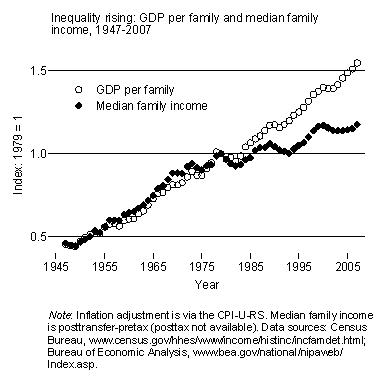

Here’s the problem (more discussion here):

There are two linked components to this rise in inequality: the surge in incomes for those at the top of the distribution and the slow growth of incomes for those in the middle and at the bottom.

Is this really a problem? Would it be better if income inequality were reduced? I think so, for the following reasons.

1. Fairness. Market processes have produced enormous incomes for various financial operators, CEOs, entrepreneurs, athletes, and entertainers in recent decades. A good bit of this is due to luck — being in the right place at the right time, genetic talent, having the right parents or teacher or coach, and so on. I don’t mind some inequality due to luck, and I recognize that monetary incentives are helpful. But the current (or recent, I should say;Â the downturn will reduce top incomes somewhat) magnitude of inequality in America strikes me as unfair. An income of several hundred million dollars when the minimum wage gets you about $15,000 is too much inequality. What’s the proper amount of income inequality? I don’t have a precise answer, but that doesn’t mean it’s wrong to feel that our current level is excessive.

2. Inequality’s consequences. Even if you don’t worry about exorbitant incomes in and of themselves, there’s no avoiding the fact that they have consequences for the incomes and well-being of Americans in middle and lower parts of the distribution. The social pie isn’t zero-sum. But our economy hasn’t grown faster in the past few decades than it did before, so the dramatic jump in incomes among those at the top has come in part at the expense of the rest of us. The following chart offers one way to see this. It shows GDP per family and median family income over the past six decades. Relative to growth of the economy, incomes in the middle (and below) have increased slowly since the 1970s.

As Robert Frank has pointed out, super-high incomes also have led to an arms race in consumption, especially in housing. Spending among the rich has escalated dramatically, encouraging middle- and upper-middle-class households to take on more and more debt in order to keep pace.

Over the past decade a number of social scientists have looked at the effect of inequality on other societal outcomes. We have studies suggesting that inequality is bad for education, health, crime, economic growth, economic mobility, civic engagement, political participation, political influence, and political polarization. I’m not convinced that all of these findings are correct, but some of them are quite plausible.

So what should we do? Stay tuned.