[My reflections on Britain since the Seventies](https://crookedtimber.org/2013/04/10/britain-since-the-seventies-impressionistic-thoughts/) the other day partly depended on a narrative about social mobility that has become part of the political culture, repeated by the likes of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown and recycled by journalists and commentators. In brief: it is the conventional wisdom. That story is basically that Britain enjoyed a lot of social mobility between the Second World War and the 1970s, but that this has closed down since. It is an orthodoxy that can, and has, been put in the service of both left and right. The left can claim that neoliberalism results in a less fluid society than the postwar welfare state did; the right can go on about how the left, by abolishing the grammar schools, have locked the talented poor out of the elite. And New Labour, with its mantra of education, education, education, argued that more spending on schools and wider access to higher education could unfreeze the barriers to mobility. (Senior university administrators, hungry for funds, have also been keen to promote the notion that higher education is a social solvent.)

[click to continue…]

{ 87 comments }

Tim Sullivan responds to my post at _OrgTheory._

bq. The point of the AA story, though, was not that organizations are perfectly efficient but that organizations face tradeoffs, and it can be useful to acknowledge those tradeoffs explicitly and to understand the economic architecture of organizations because it makes the situation of the average employee, manager, executive more comprehensible. In the AA case, they had a terrible website (which reflected plenty of other dysfunction within the company), and yet to do the job that AA aspired to (that is, flying people and stuff all over the world), you have to build a big, complicated organization that does lots of things all at once – managing fuel contracts, negotiating with pilots and flight attendants, setting prices, and so on. And organizing all of this involves a lot of tradeoffs. … Ray and I aren’t suggesting that orgs can’t be full of politics, power plays, bad managers, ridiculous HR departments, and so forth. They clearly are — but you have to accept these realities when you decide that there’s something that you want to do that will be best accomplished as a group of bosses and employees. The trick is not to ignore them or pretend they don’t exist, but to understand how and why they are produced, to recognize that sometimes apparent inefficiencies are the result of being organized, and understand the difference between tradeoffs and the _truly_ ridiculous and pointless aspects of organizational life.

I think that the nub of the disagreement is best summed up in one half-sentence here, where Tim suggests that “you have to accept these realities when you decide that there’s something that you want to do that will be best accomplished as a group of bosses and employees.” The point of the alternative perspective I set out is that there _isn’t_ any moment when a collective ‘you’ of bosses and employees, with a common interest in getting something done, decides this. The actual ‘you’ who makes the decisions is a very specific ‘you’ with a very specific set of interests. It is the ‘you’ who is in charge (or, if you want to get all old-style, the ‘you’ who is a capitalist). There is a literature of course in organizational economics, which talks about ‘team production functions,’ and how teams might rationally, if they wanted to get stuff done and minimize shirking, assign oversight to a hierarchically empowered actor. But in an economy which is not organized around cooperatives, very few private enterprises will originate in this way. Instead, they will originate with decisions by owners of capital, who will empower managers (a group which may, or may not, overlap with the owners of capital) to hire workers. The logic will be different, obviously, in non-profits and the government sector, but less different than you might imagine, as both these sectors become more and more like private enterprise.

[click to continue…]

{ 40 comments }

Via “The Browser”:http://www.thebrowser.com a “rather wonderful unravelling”:http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/public/article1243205.ece of the various identities associated with independent scholar A.D. Harvey, who apparently leaves posers like John Lott spluttering in the dirt. The piece is long but worthwhile: at its best, it reads like a combination of A.J. Symon’s _Quest for Corvo_ and what _At-Swim-Two-Birds_ might have been if Flann O’Brien were a tenured professor of history:

bq. Even for holders of tenured university positions, scholarship can make for a lonely life. One spends years on a monograph and then waits a few more years for someone to write about it. How much lonelier the life of an independent scholar, who does not have regular contact, aggravating as that can sometimes be, with colleagues. Attacking one’s own book can be seen as an understandable response to an at times intolerable isolation. How comforting to construct a community of scholars who can analyse, supplement and occasionally even ruthlessly criticize each other’s work. I’ve traced the connections between A. D. Harvey, Stephanie Harvey, Graham Headley, Trevor McGovern, John Schellenberger, Leo Bellingham, Michael Lindsay and Ludovico Parra, but they may be part of a much wider circle of friends. … some of Harvey’s own mystifications leave an unpleasant taste. It is not only that the apparent practice of submitting articles under fictitious names to scholarly journals might well have a chilling effect on the ability of really existing independent scholars to place their work. Nor is it just the embarrassment caused to editors who might in an ideal world have taken more pains to check the contributions of Stephanie Harvey or Trevor McGovern, but who accepted them in good faith, partly out of a wish to make their publications as inclusive as possible.

{ 54 comments }

The 1970s have been in my mind over the past few days, not only for the obvious reason, but also because I visited the Glam exhibition at Tate Liverpool last weekend. Not only were the seventies the final decade of an electrical-chemical epoch that stretched back to the late nineteenth-century, they were also the time when the sexual and political experimentation of the 1960s and a sense of being part of a cosmopolitan world order became something for the masses, for the working class, and when the old social order started to dissolve. In the experience of many people, the sixties happened in the seventies, as it were.

But my main thoughts, concerning Britain at any rate, have been about social division, and about some oddly paradoxical features of British life before Thatcher. There’s a very real sense in which postwar British society was very sharply divided. On the one hand, it was possible to be born in an NHS hospital, to grow up on a council estate, to attend a state school, to work in a nationalised industry and, eventually (people hoped), to retire on a decent state pension, living entirely within a socialised system co-managed by the state and a powerful Labour movement. On the other, there were people who shared the experience of the NHS but with whom the commonality stopped there: they were privately educated, lived in an owner-occupied house and worked in the private sector. These were two alternate moral universes governed by their own sets of assumptions and inhabited by people with quite different outlooks. Both were powerful disciplinary orders. The working class society had one set of assumptions – welfarist, communitarian, but strongly gendered and somewhat intolerant of sexual “deviance”; middle-class society had another, expressed at public (that is, private) schools through institutions like compulsory Anglican chapel. Inside the private-sector world, at least, there was a powerful sense of resentment towards Labour, expressed in slogans about “managers right to manage” and so on that later found expression in some of the sadism of the Thatcher era towards the working-class communities that were being destroyed. Present too, at least in the more paranoid ramblings of those who contemplated coups against Labour, was the idea that that the parallel socialised order represented a kind of incipient Soviet alternative-in-waiting that might one day swallow them up.

[click to continue…]

{ 104 comments }

I was going to review a couple of new books I picked up – The Lost Art of Heinrich Kley, Volume 1: Drawings & Volume 2: Paintings & Sketches

. (Those are Amazon links. You can get it a bit cheaper from the publisher. And see a nifty little video while you’re there.) But now I seem to have lost vol. 1 of Lost Art. Turned the house over, top to bottom. Can’t find it anywhere! Oh, well. Bottom line: I’ve been collecting old Kley books for a while. It’s fantastic stuff – if you like this kind of stuff – and these new books contain a wealth of material I had never seen. I wish, I wish the print quality in vol. 1 were higher because the linework really needs to pop. The color stuff in volume 2 is better, and harder to come by before now. One editorial slip. Kley’s Virgil illustrations come from a ‘travestiert’ Aeneid, by Alois Blumauer, not a ‘translated’ one. Parody stuff. (There, I just had to get my drop of picky, picky pedantry in there.) That said, the editorial matter in both volumes is extremely interesting. Volume 2 has a great Intro by Alexander Kunkel and a very discerning little Appreciation by Jesse Hamm, full of shrewd speculations about Kley’s methods. He’s a bit of a mystery, Kley is.

The books are in a Lost Art series that is clearly a labor of love for Joseph Procopio, the editor.

In honor of our Real Utopias event, I’ll just give you Kley on politics and metaphysics. (These particular images aren’t from these new volumes, but they’re nice, aren’t they?)

Click for larger.

{ 4 comments }

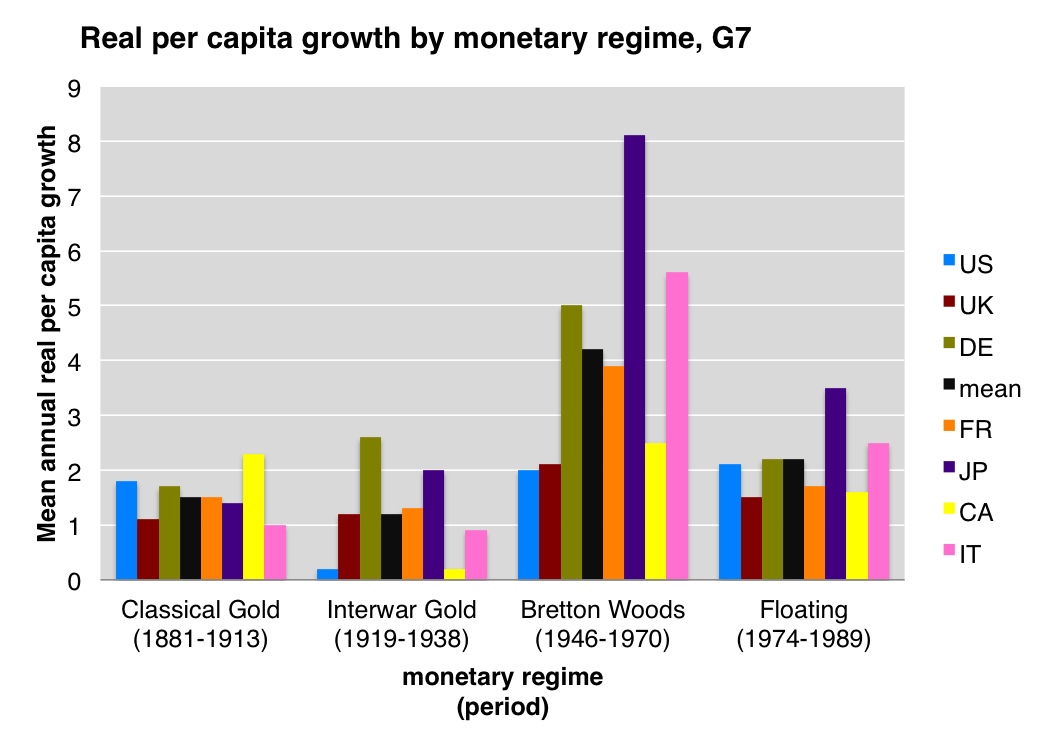

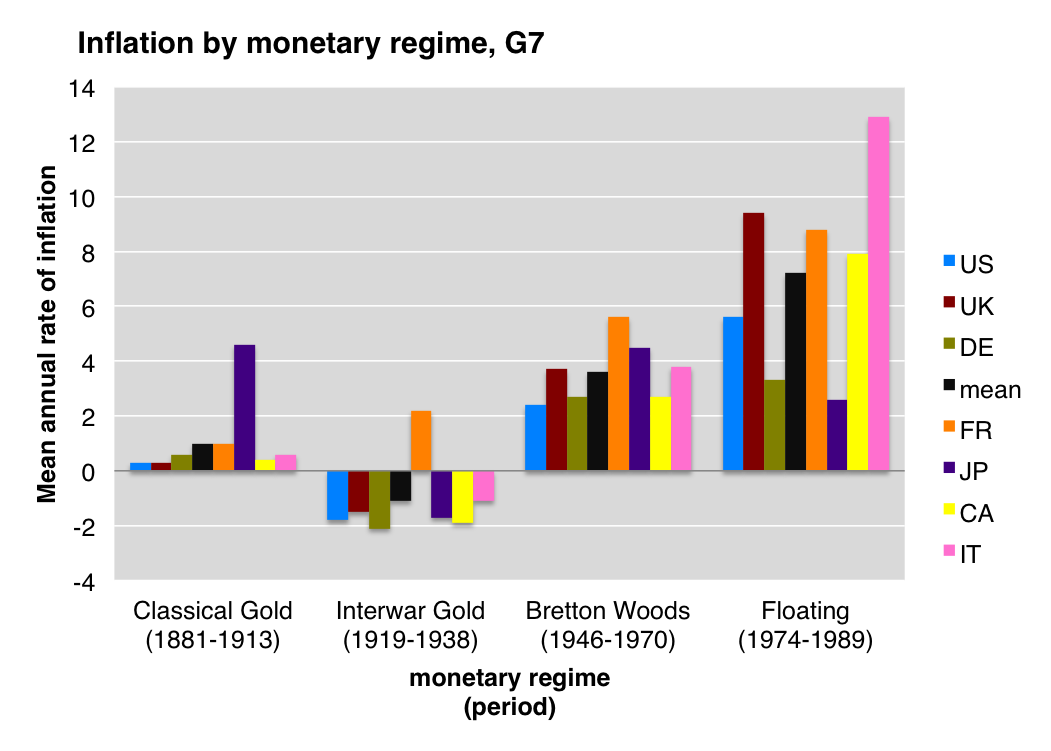

Was the gold standard a golden age, or a gilded one? How does it compare to later monetary regimes? I mean, we know the gold standard was terrible for the US, but what about other countries? I know you want to know, without having to dig in data appendices, so I made you some charts. Because I love you that much. (But not enough to extend the floating exchange rate regime data down to the present; that’s actual work.)

Data from table 1, Michael Bordo, “The Gold Standard, Bretton Woods and other Monetary Regimes: An Historical Appraisal,” NBER working paper no. 4310.

{ 36 comments }

In The Reactionary Mind, I wrote:

One of the reasons the subordinate’s exercise of agency so agitates the conservative imagination is that it takes place in an intimate setting. Every great blast—the storming of the Bastille, the taking of the Winter Palace, the March on Washington—is set off by a private fuse: the contest for rights and standing in the family, the factory, and the field. Politicians and parties talk of constitution and amendment, natural rights and inherited privileges. But the real subject of their deliberations is the private life of power: “Here is the opposition to woman’s equality in the state,” Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote. “Men are not ready to recognize it in the home.” Behind the riot in the street or debate in Parliament is the maid talking back to her mistress, the worker disobeying her boss. That is why our political arguments—not only about the family but also the welfare state, civil rights, and much else—can be so explosive: they touch upon the most personal relations of power.

Feminism—and the backlash against it—is the paradigm case of the battle over the private life of power. As historians have shown, the attack on Women’s Lib gave the modern conservative movement what it needed to achieve its counterrevolution in 1980. But to understand why that was the case, we have to recall just how radical feminism truly was: it sought to disrupt concrete and tangible relationships in the most private relations of power. [click to continue…]

{ 123 comments }

There’s already plenty of commentary, here and elsewhere on Margaret Thatcher. Rather than add to it, I’d like to compare the situation when she assumed the leadership of the Conservative Party with the one we face now. As Corey points out in his post

In the early 1970s, Tory MP Edward Heath was facing high unemployment and massive trade union unrest. Despite having come into office on a vague promise to contest some elements of the postwar Keynesian consensus, he was forced to reverse course. Instead of austerity, he pumped money into the economy via increases in pensions and benefits and tax cuts. That shift in policy came to be called the “U-Turn.”

Crucially, Heath was defeated mainly as a result of strikes by the coal miners union.[1]

From the viewpoint of conservatives, the postwar Keynesian/social democratic consensus had failed, producing chronic stagflation, but the system could not be changed because of the entrenched power of the trade unions, and particularly the National Union of Miners. In addition, the established structures of the state such as the civil service and the BBC were saturated with social democratic thinking.[2]

Thatcher reversed all of these conditions, smashing the miners union and greatly weakening the movement in general, and promoting and implementing market liberal ideology as a response to the (actual and perceived) failures of social democracy. Her policies accelerated the decline of the manufacturing sector, and its replacement by an economy reliant mainly on the financial sector, exploiting the international role of the City of London.

Our current situation seems to me to be a mirror image of 1975. Once again the dominant ideology has led to economic crisis, but attempts to break away from it (such as the initial swing to Keynesian stimulus) have been rolled back in favour of even more vigorous pursuit of the policies that created the crisis. The financial sector now plays the role of the miners’ union (as seen in Thatcherite mythology) as the unelected and unaccountable power that prevents any positive change.

Is our own version of Thatcher waiting somewhere in the wings to take on the banks and mount an ideological counter-offensive against market liberalism? If so, it’s not obvious to me, but then, there wasn’t much in Thatcher’s pre-1975 career that would have led anyone to predict the character of her Prime Ministership.

fn1. I was too far from the scene to be able to assess the rights and wrongs of these strikes or the failed strike of the early 1980. It’s obvious that the final outcome was disastrous both for coal miners and for British workers in general, but not that there was a better alternative on offer at the time.

fn2. The popular series, Yes Minister, was essentially a full-length elaboration of this belief, informed by public choice theory

{ 33 comments }

Last month, New Yorker reporter Jon Lee Anderson turned twelve shades of red when he was challenged on Twitter about his claim in The New Yorker that Venezuela was “one of the world’s most oil-rich but socially unequal countries.” A lowly rube named Mitch Lake had tweeted, “Venezuela is 2nd least unequal country in the Americas, I don’t know wtf @jonleeanderson is talking about.” Anderson tweeted back: “You, little twerp, are someone who has sent 25,700 Tweets for a grand total of 169 followers. Get a life.” Gawker was all over it.

What got lost in the story though is just how wrong Anderson’s claim is. In fact, just how wrong many of his claims about Venezuela are. [click to continue…]

{ 90 comments }

In the recent TLS I have an essay on Benn Steil’s new book on Bretton Woods. Unlike some notices, mine is critical. You can read mine here. If you’re interested in the theory, put forward in Steil’s book, that Harry Dexter White caused US intervention in World War II, read below the fold. If you’re more interested in the late Baroness Thatcher, please carry on down to the other posts for today.

{ 26 comments }

To get a sense of why conservatives in Britain of a certain age revere Margaret Thatcher, check out this clip of her “You turn if you want to, the lady’s not for turning” speech at the Conservative Party Conference in October 1980.

The context (my apologies to the Brits in the audience; this stuff can be like ancient Greek to us Yanks): In the early 1970s, Tory MP Edward Heath was facing high unemployment and massive trade union unrest. Despite having come into office on a vague promise to contest some elements of the postwar Keynesian consensus, he was forced to reverse course. Instead of austerity, he pumped money into the economy via increases in pensions and benefits and tax cuts. That shift in policy came to be called the “U-Turn.”

Fast forward to 1980: Thatcher had been in power for a year, and the numbers of unemployed were almost double that of the Heath years. Thatcher faced a similar call from the Tory “Wets” in her own party—conservatives who weren’t keen on her aggressive free-market counterrevolution—to do a U-Turn, and many expected she would. This was her response. [click to continue…]

{ 26 comments }

I presume it is a bit silly to point to any obituaries. So, instead, a heartwarming story. A few weeks before he died Eric Heffer, in one of his last interviews, Eric Heffer told a story against Neil Kinnock. (If you are too young to remember Heffer, well, here’s wikipedia). He, Heffer, was dying, and one evening, walking down a corridor in the Commons, he got to the point that he couldn’t walk any further. He thought he was alone but Mrs Thatcher was several feet behind him. Seeing his distress she made him put his arm round her, and walked him to a nearby office, made him a cup of tea, and sat with him while they waited for a nurse. His observation, about Neil Kinnock, was that he would have walked straight by.

It turns out that Heffer and Thatcher were friends of sorts; similarly Thatcher and Allan Adams. (See Frank Field on Thatcher’s liking for socialist company). The first 6 years of my political life was devoted to opposing nearly everything Thatcher did (including the Falklands War, about which I have changed my mind; the exception: sale of council houses), and that only ended because I moved somewhere that I could oppose what Reagan was doing instead. But there’s plenty of space on the internet for people who want to speak ill of the dead — I just thought I would tell a story I heard about 22 years ago and is not, as far as I can find, recorded elsewhere.

{ 70 comments }

So, I got these two packages from Sweden today. Obviously, this is part two of this episode. Which Jon Ronson wrote about here.

I’m not going to try to analyze the books I received yet, except to note that yes, that’s clearly the Giant Rat of Sumatra speaking the slogan from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, “BORN” as a reference to the original Being or Nothingness and, uh, probably some other stuff. One of the books says “Facsimile” and the other doesn’t. I already confirmed with Jon Ronson that he got one too.

I won’t attempt any further analysis for now. But if anyone else got one (or two) please write in to say…

{ 14 comments }

Ray Fisman and Tim Sullivan (who I know a little and like) are blogging about their recent book on organization management, _The Org_ (“Powells”:http://www.powells.com/partner/29956/biblio/9780446571593?p_ti, “Amazon”:http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0446571598/ref=as_li_ss_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=0446571598&linkCode=as2&tag=henryfarrell-20) over at “OrgTheory.net”:http://www.orgtheory.net at the moment. It’s both a very good book and an excellent introduction to a particular style of thinking about organizations. The book starts with Ronald Coase’s insights about the relative benefits of contract and hierarchy, and goes from there. Much of the book is devoted to showing how these insights travel across a wide variety of different contexts – Baltimore policing (building on “Peter Moskos’ sociology”:https://crookedtimber.org/2009/07/21/discretion-and-arrest-power/), Christian preaching and the like. Much of the book is also devoted to explaining why apparently frustrating aspects of organizations have a rationale, and may even be the best way of accomplishing something or somethings, given the complex and multiple needs, internal incentive problems and so on. More succinctly, the book sets out to show how the world that Dilbert inhabits may not be the best of all possible worlds, but is better than we realize at first glance, and actually less dysfunctional than the obvious alternatives. It provides a lot of detail and case study to back up this basic claim. And it is in an entirely different league of intelligent argument from other books aimed at business readers.

All this said, I tend to view organizations from a different perspective than the authors, one which didn’t really get any sustained attention in the book. Fisman and Sullivan build on two major traditions in organization and management – one stemming from Frederick Taylor, and the other from Chester Barnard. Taylor emphasized the value of overt incentives, monitoring and information in achieving organizational efficiencies. Barnard emphasized the benefits of fuzzier notions of corporate culture, in creating a more diffuse, but likely valuable set of benefits in interactions between workers and management. Fisman and Sullivan start off with a Coaseian version of Taylor’s arguments, but weave in some Barnardian arguments about the benefits of corporate culture as the book progresses. A good organization is one with clear, well designed incentives, _and_ with a culture of trust.

{ 25 comments }

A very wide range of issues have been raised in the many interesting postings and comments during the Crooked Timber seminar about my book Envisioning Real Utopias which ran from March 18-28. In what follows I will give at least a brief response to the core themes of each of the eight contributions to the seminar. I will organize my reflections in the order of the contributions in the symposium.

“[PDF version here]”:https://crookedtimber.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Erik-Olin-Wright-Reflections-on-Real-Utopias-Crooked-Timber-symposium.pdf

[click to continue…]

{ 10 comments }