This afternoon I ended up reading [this Vox story](http://www.vox.com/2014/8/6/5973653/the-federal-government-tried-to-rank-colleges-in-1911) about an effort to rank US Universities and Colleges carried out in 1911 by a man named Kendric Charles Babcock. On Twitter, [Robert Kelchen remarks](https://twitter.com/rkelchen/status/496746198112686082) that the report was “squashed by Taft” (an unpleasant fate), and he [links to the report itself](https://ia700504.us.archive.org/0/items/classificationof01unit/classificationof01unit.pdf), which is terrific. Babcock divided schools into four Classes, beginning with Class I:

And descending all the way to Class IV:

Babcock’s discussion of his methods is admirably brief (the snippet above hints at the one sampling problem that possibly troubled him), so I recommend you [read the report yourself](https://ia700504.us.archive.org/0/items/classificationof01unit/classificationof01unit.pdf).

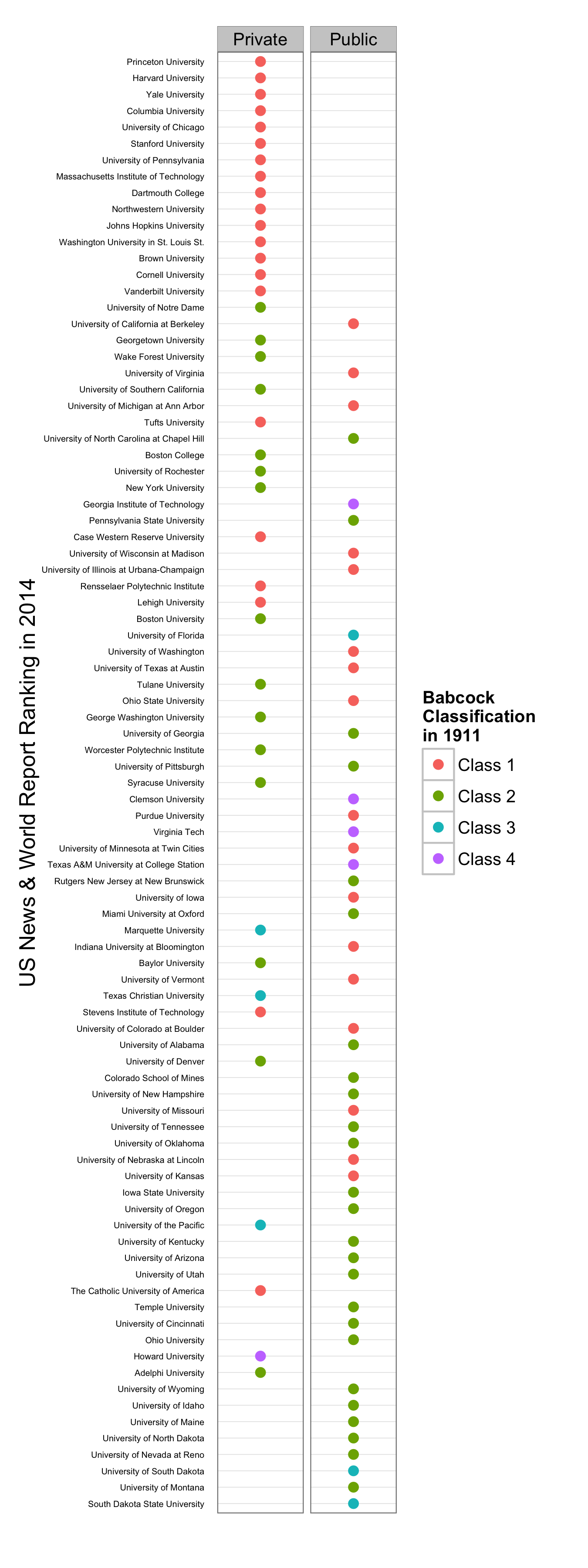

University reputations are extremely sticky, the conventional wisdom goes. I was interested to see whether Babcock’s report bore that out. I grabbed the US News and World Report [National University Rankings](http://colleges.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com/best-colleges/rankings/national-universities) and [National Liberal Arts College Rankings](http://colleges.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com/best-colleges/rankings/national-liberal-arts-colleges/) and made a quick pass through them, coding their 1911 Babcock Class. The question is whether Mr Babcock, should he return to us from the grave, would be satisfied with how his rankings had held up—more than a century of massive educational expansion and alleged disruption notwithstanding.

It turns out that he would be quite pleased with himself.

Here is a dotplot of the 2014 USNWR National University Ranking, where the dots are color-coded for Babcock Class. There are two panels, one on the left for Private Universities, and one on the right for Public Universities. USNWR’s highest-ranked school at the moment is Princeton, and it is at the top of the dotplot. You read down the ranking from there.

You can get a [larger image](http://kieranhealy.org/files/misc/babcock-universities.png) or a [PDF version of the figure](http://kieranhealy.org/files/misc/babcock-universities.pdf) if you want a closer look at it.

As you can see, for private universities, especially, the 1911 Babcock Classification tracks prestige in 2014 very well indeed. The top fifteen or so USNWR Universities that were around in 1911 were regarded as Class 1 by Babcock. Class 2 Privates and a few Class 1 stragglers make up the next chunk of the list. The only serious outliers are the [Stevens Institute of Technology](http://stevens.edu) and the [Catholic University of America](http://cua.edu).

The situation for public universities is also interesting. The Babcock Class 1 Public Schools have not done as well as their private peers. Berkeley (or “The University of California” as was) is the highest-ranked Class I public in 2014, with UVa and Michigan close behind. Babcock sniffily rated UNC a Class II school. I have no comment about that, other than to say he was obviously right. Other great state flagships like Madison, Urbana, Washington, Ohio State, Austin, Minnesota, Purdue, Indiana, Kansas, and Iowa are much lower-ranked today than their Class I designation by Babcock in 1911 would have led you to believe. Conversely, one or two Class 4 publics—notably Georgia Tech—are much higher ranked today than Babcock would have guessed. So rankings are sticky, but only as long as you’re not public.

I also did the same figure for Liberal Arts Colleges, almost all of which are private, so this time there’s just the one panel:

You can get a [larger image](http://kieranhealy.org/files/misc/babcock-colleges.png) or a [PDF version of the figure](http://kieranhealy.org/files/misc/babcock-colleges.pdf) if you want a closer look at it.

Again, there is a substantial degree of stability over the course of the century. Here we see a bit more evidence of some movement up by colleges that Babcock put in Class II—Swarthmore, for example, as well as Middlebury and Pomona. The Class I schools that seem to have fallen from favor most are Knox, Lake Forest, and Goucher colleges.

Now, some caveats. First, because I was more or less coding this stuff while eating my lunch, I have not attempted to connect schools which Babcock did rate with their current institutional descendants. So, for example, some technical, liberal arts, or agricultural schools that he classified grew into or were absorbed by major state universities in the 20th century. These are not on the charts above. We are only looking at schools that existed under their current name (more or less—there are one or two exceptions) in 1911 and now. Second, higher Education in the U.S. really has changed a lot since 1911. In particular the postwar expansion of public education introduced many new and excellent public universities, and over the course of the twentieth century even some decent private ones emerged and came to prominence (such as [my own](http://www.duke.edu), which competes with a nearby Class II school). This biases things in favor of the seeming stability of the rankings, because in his own data Babcock had the luxury of not having to classify schools that did not yet exist.

We can add these in a final, rather large, chart for the National University data.

You can get a [larger image](http://kieranhealy.org/files/misc/babcock-all-universities.png) or a [PDF version of the figure](http://kieranhealy.org/files/misc/babcock-all-universities.pdf) if you want a closer look at it.

Now the coding includes the pink “None” category, which adds universities that appear in the USNWR rankings but which are not in Babcock, either because they did not exist at all in 1911, or had not yet taken their present names. In fairness to him, the new additions still leave Babcock’s classification looking pretty good. On the private side, Duke, Caltech, and Rice are added to the upper end of the list, and a number of new private schools further down.

Meanwhile on the public side you can see the appearance of the 20th century schools, most notably the whole California system. The UC System is an astonishing achievement, when you look at it, as it propelled five of its campuses into the upper third of the table to join Berkeley. But the status ordering that was—take your pick; these data can’t settle the question—observed, intuited, or invented by Babcock a century ago remains remarkably resilient. The old regime persists.

*Note:* Updated August 8th to correct some coding errors.

{ 27 comments }

sPh 08.07.14 at 12:31 am

Reality-basing forces me to note that although Washington University in St. Louis ranks high in both 1911 and 2014 its reputation took a U-shaped course in the years between. From being a national school with an international reputation in 1880-1920 WU retreated to being a regional private university with a large commuter population by 1950 – albeit one with a full set of schools and departments. It took a massive effort (and a massive cash infusion) from 1970-1990 to restore the restructured WUSTL to its former prominence.

Kevin V 08.07.14 at 12:48 am

Wonderful analysis. Why can’t you blog more?

And I wonder what the most plausible mechanisms for continued social dominance would be. Path-dependence is likely a factor, but what prevents more movement up and down the ladder?

Matt 08.07.14 at 2:37 am

Wonderful analysis. Why can’t you blog more?

Let me second that.

Babcock had the luxury of not having to classify schools that did not yet exist.

Looks like shirking to me. He should have just projected things out to figure out how future, not-yet-existant schools would do, based on past performance of similar, actually existing schools.

John Quiggin 08.07.14 at 3:05 am

On the public vs private point, it’s important to observe that the top private schools haven’t grown in undergraduate student numbers since the 1950s, while most of the public schools grew strongly until the late 1970s.

John Quiggin 08.07.14 at 3:08 am

Some related points here.

JakeB 08.07.14 at 4:08 am

Well, damn my wig.

maidhc 08.07.14 at 5:20 am

John Quiggin: What about the ANU, which was founded in 1946? I see some of your commenters made the same point. Also Simon Fraser (1963) gets some respectable rankings. Even Cal-Poly (1901).

John Quiggin 08.07.14 at 8:00 am

@7 Entry to the list can happen with a new or greatly expanded funding source. For example, ANU was created by the national government as a research-only institution modelled on IAS at Princeton, and Kieran mentioned the massive expansion of UC following the master plan of 1960. Going more broadly, universities in China are bound to ascend the status hierarchy.

Relatedly, its possible for changes in funding models to shift the relative status of whole groups (Ivies vs state flagships in the US, unitechs vs 1970 vintage in Oz, maybe redbricks vs polytechnics in the UK).

Within any given system, these shifts are fairly modest, as indicated by the handful of examples you cite. More crucially, they have almost nothing to do with choices made at the university level. For example, ANU ranks above the nearby University of Canberra because of the historical circumstances of their creation, not because one was better run than the other.

harry b 08.07.14 at 8:42 am

Interesting that even then there was no interest in value-added. From the point of view of the society regulating and (to whatever degree it does) paying for college, what matters is how much is added to their preparation by the institutions they attend (and what they are prepared for). Even from the point of view of the student, the quality of the learning that goes on in the college matters some. But Babcock is only interested in how well prepared the students are, regardless of what the college has added.

Olle J. 08.07.14 at 10:34 am

@ harry b #9

A couple of years back I spent a term at Oxford (not at Brookes University, the other one). People in general was, of course, smart and well read. However, after some I noticed that most of the grad students hadn’t been undergrads at Oxford. It was mostly the same with PhD (or DPhil, as they call it – because they are, of course, special*) and professors. I suggested that perhaps the University of Oxford was a deskilling institution but didn’t get much support for this hypothesis from my peers.

* (My wife loves to say that I’m special, with a sarcastic smile – with this implying eating paste-special – in front of my mother. My mother, never noticing the subtext, always adds that ‘of course Olle’s special’ and pinches me on the cheek, or something like that, while my wife giggles silently behind her. I’m 36 years old, with a degree, a wife and a daughter…)

q 08.07.14 at 5:50 pm

The spirit of Edward Tufte has possessed me and forced me to suggest that the final chart would be much clearer if the schools not ranked by Babcock were marked with, say, an open uncolored circle, or a light gray one. The mass 0f purple obscures whatever interesting data there is.

Ogden Wernstrom 08.07.14 at 8:35 pm

I find the non-California examples in Babcock:

Georgia Tech, listed in the Class IV column, as Georgia School of Technology, on p. 8 of Babcock’s document. Today, the full name is Georgia Institute of Technology.

Virginia Tech, listed in the Class IV column, as Virginia Polytechnic Institute, on p. 14 of Babcock’s document. (In 1911, the full name was Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College and Polytechnic Institute. Today, the full name is Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.)

I do not expect perfection from a lunchtime pastime.

Thank you for showing us this evidence of the long-term persistence of institutional rankings.

Andrew Smith 08.07.14 at 9:11 pm

Those US News rankings are fairly silly, though. Take a field like Computer Science, and grads from Princeton, U of Chicago, or Duke are not in the same level of demand as grads from (obviously) MIT or University of Washington way down the list. Lots of jobs in software at the moment.

Jerry Vinokurov 08.07.14 at 9:54 pm

@13: I think if you got a CS degree from basically any of those places, you’d be fine.

If I were a less generous person, I’d suggest that the USNWR people got hold of Babcock’s efforts and just tweaked the weights of their “system” until they reproduced his results.

John Thacker 08.08.14 at 1:52 am

Duke University appears in the Babcock rankings as Trinity College (North Carolina) as a Class II school for recent graduates. This was after the first donations by Washington Duke, but fifteen years before the school changed its name for the Duke family.

Eric Rasmusen 08.08.14 at 2:08 am

I don’t know why anybody takes the US news rankings seriously if they know anything at all about academia, though I admit that that’s perhaps 5% of the US population.

bill benzon 08.08.14 at 10:21 am

@Kevin V, #2: “Path-dependence is likely a factor, but what prevents more movement up and down the ladder?”

Path dependence sounds good to me. Back in the 1980s, when I was on the faculty at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, the school decided it wanted to move from being a second tier tech school to the top tier (Cal Tech, MIT, Carnegie Mellon). I thought about the problem at that time, though not in a formal way.

A schools’ standing depends mostly on the quality of its people, its faculty and students. And those people are pipelined from secondary school through college and university to faculty posts. Unless something happens to bring a new population into the system, has happened with the massive increase in Federal aid post-Sputnik (cf Quiggan @ #8), just about the only way to move up is to convince people in a higher stream to move down to your institution, thereby bringing your institution up. That’s a hard sell.

The alternative is to be prescient enough to see the future and grab the future leaders before they’re widely recognized. That’s tough, as it requires imagination and guts.

Kieran 08.08.14 at 10:27 am

Ogden—good catch. I’ve updated the figures.

John Thacker 08.08.14 at 11:28 am

I also see Vanderbilt listed as a Class I on page 14. In the case of Duke, Babcock on page 13 only lists Trinity College (North Carolina) as Class II for recent graduates – presumably those after the initial gifts by Washington Duke. So both those private schools are listed as well. (And you teach at the Trinity College School of Arts and Sciences at Duke University, but it is I suppose easy to forget the name change.)

It does show that an infusion of money does make a difference, but in recent years people have been more likely to give to their alma maters than found a new school. I would assume that is because of a lack of Gilded Age tycoons that yet did not go to university and hence had no alma mater to contribute to, such as the Dukes, Vanderbilts, and Reynolds. (Wake Forest)

LFC 08.08.14 at 2:08 pm

The criticisms of the USNWR rankings are fairly well-known and seem at least partly valid to me. USNWR says this in its section on ‘methodology’:

The indicators we use to capture academic quality fall into a number of categories: assessment by administrators at peer institutions, retention of students, faculty resources, student selectivity, financial resources, alumni giving [!], graduation rate performance and, for National Universities and National Liberal Arts Colleges only, high school counselor ratings of colleges.

The indicators include input measures that reflect a school’s student body, its faculty and its financial resources, along with outcome measures that signal how well the institution does its job of educating students.

That all sounds very nice, but the first item — “assessment by administrators at peer institutions” — gets a weight of roughly 23%, i.e., a significant amount. USNWR assumes administrators have informed, well-grounded views of the quality of peer institutions; but do they, or do they just repeat the conventional wisdom, thus perpetuating a sort of closed loop and helping ensure that reputations are “sticky” even when actual conditions/facts change? Moreover, this “assessment by administrators” is an inherently subjective criterion, unlike the objective metrics (retention rate etc) that are thrown into the mix. If I were a h.s. student applying to college, I don’t think I’d pay too much attention to the USNWR rankings except as an indication of the conventional wisdom.

Kieran Healy 08.08.14 at 2:31 pm

John Thacker—I knew about Duke’s presence was a bit queasy about including it; I’d missed Vandy and have updated the figures.

Jim Blackburn 08.08.14 at 11:05 pm

There are very distinguished institutions included in all of the referenced “listsâ€. One trend that seems to have continued over the century is that the “rich get richerâ€. Colleges and universities, which attract well prepared and/or well financed students tend to be included, and institutions, who do the heavy-lifting of higher education tend not to make the “cut’.

It seems unfortunate that IHE, which enroll the less affluent and often less well -prepared and then transform them in acts of great “value-addedness†into persons of worth and renown receive less mention and praise than the well-established and well financed. Given the importance of HED in providing social mobility, would not it be useful to include among the criteria for USNWR, etc. the percentage of Pell Grant eligible students among an institution’s alumni?

Damien Warman 08.10.14 at 8:41 am

I wish to echo q at 11 in regretting that this otherwise rather interesting work is for me completely destroyed by my (rather standard) colour-blindness. A shading, a differing stroke at the boundary, a different choice of palette, …

Granite26 08.11.14 at 2:05 pm

Two points:

1: Where there ranked private schools that didn’t survive to the modern day? I would think schools that failed or fell off the rankings would also be interesting.

2: Every one of the ‘Class IV’ schools that now rank in the modern, public list is in the South. Major growth of the Southern economy, much? (The private school, Howard, is apparently in DC, which is pretty close.

JJC78 08.11.14 at 8:18 pm

I think it’s interesting that, with the exception of CUA, Catholic schools seem to have either risen in reputation with the rise of the Catholic middle-class or were systematically underrated by Babcock, or perhaps a bit of both.

Tyler Ouellet 08.12.14 at 2:53 pm

Great analysis, hard to read graphs.

You have too many data points to use a graph like that vertical. Try it horizontal at least, so you can see more data points without needing to scroll. Graph would work well on paper on a large screen, but it it difficult to see completely on my 15″ macbook. I would have also aggregated the data a bit more, maybe by region? The graphs don’t give the full power of delivering your strong analysis. I think it is because I am looking at it only in small sections because of size issues.

There were a few other got points by others on shading and color use as well.

Bryce 08.12.14 at 7:35 pm

I’m curious about the extent to which the 1911 rankings were influenced by whether the schools were co-ed. It looks like this might be a particularly significant effect in the liberal arts college rankings, where the top four colleges in 2014 that were tier 2 in 1911 are all historically co-ed, while the top seven colleges in 2014 that were tier 1 in 1911 are all historically single-sex. I’d be willing to do the coding for men/women/co-ed myself; would you be willing to share the data so that I don’t have to duplicate your effort?

Comments on this entry are closed.