Imagine that you’re a person who is obsessed with airplanes. Naturally

you’re excited when everyone starts talking about this big new book,

*Aviation in the 21st Century.* You get your copy and start

reading. Just as you’d hoped, there’s a detailed discussion of the

flight characteristics of a vast variety of plane types and a

comprehensive record of different countries’ commercial fleets, from the

beginning of aviation until today, plus a few artfully chosen

illustrations of classic early planes. But long stretches of the book

are quite different. They are devoted to the general principle that, in

an atmosphere, heavier objects fall faster than light ones, building up

to the universal law that lighter-than-air objects will float. Finally,

in the conclusion, you find some bleak reflections on the environmental

consequences of air travel – hardly mentioned til now – and a plea for

the invention of some new technology that will allow fast air travel

without the use of fossil fuels. How do you feel, when you set the book

down? You would be grateful for the factual material – even if the good

stuff is mostly relegated to the online appendices. You would be

impressed by the rigorous logic with which the principle of buoyancy was

developed, and admire the author’s iconoclastic willingness to break

with the orthodox view that all motion takes place in a vacuum. You

probably share the author’s hopes for some way of eliminating the carbon

emissions from air travel. But you might also find yourself with the

uneasy feeling that the whole is somehow less than the sum of its parts.

You’re probably not into airplanes. But reading *Capital In the

21st Century,* you may have experienced a similar unease. You

know the great social change the book is motivated by is the long run

trajectory of income distribution – high in the 19th century, declining

through much of the 20th century, and rising in recent decades. You

understand that the central theoretical claim of the book is that

“*r>g*” creates a secular tendency for income to

concentrate. But it’s hard to find an account of how the universal logic

accounts for the concrete history. (It’s striking, for instance, that

the book does not contain a table or figure comparing *r*

and *g* historically.) In contrast to the comprehensive

account of the evolution of wealth shares in a dozen countries, the

evidence linking this evolution to the supposed underlying dynamics is

sparse and speculative.

The fundamental source of this disconnect is the two different senses in

which Piketty uses the term “capital.” In the historical material, it is

the observable aggregate of property claims, measured in money. But in

the theoretical passages, it is a hypothetical aggregate of physical

means of production. As a result, the theory and the history don’t

really connect.

In treating capital as a money value when he measures it, and a physical

quantity when he theorizes about it, Piketty follows the practice of

most economists. I am far from the first one to point to problems with

this approach. Heterodox critics who focus on this choice often invoke

the Cambridge capital controversies, and suggest there is something

logically inconsistent about the idea of a quantity of capital. In my

opinion, these criticisms do not quite hit the mark. “K” and the formal

models it is part of are tools for abstracting away from some aspects of

observable reality in order to focus on others. Joan Robinson was

certainly right that growth models of the kind used by Piketty cannot be

derived from generic assumptions about production and exchange. But so

what? The question to ask about a model is not whether it is logically

derivable from first principles, but whether it gives a good description

of the phenomena we are interested in. There is no reason in principle

that a model of capital as a physical stock cannot capture important

regularities in the behavior of capital as observable money wealth. It

just happens that for for the central questions of *Capital in the

21st Century,* it does not.

Probably this is familiar to most people reading this, but let’s recap

Piketty’s formal argument. He begins with two laws. The first decomposes

the profit share into the rate of return on capital and the ratio of the

capital stock to national income: *alpha = r

beta.* *Alpha* is the share of capital income in

total income, *r* is the average return on capital, and

*beta* is *K / Y*, the capital stock

(*K*) as a share of total income (*Y*). This

“law” has been criticized as vacuous on the grounds that it is an

accounting identity – an equation that is true by definition. Again, I

think this is unfair. Yes, it is an accounting identity, but an

accounting identity read in a particular way. It says that there is a

given stock of capital, which produces a certain stream of income; this

can then be compared to total national income to give the capital share.

We could write the identity in other ways. The same identity could be

read in other ways, for instance, *K = alpha Y/r.* Formally

this is the same but it means something different. It means that a

certain share of output is first claimed by a class of capital owners,

and then their tradable claims on this income are assigned a value based

on a discount factor *r.*

The loose articulation between Piketty’s historical material and his

formal analysis comes from his decision to interpret the identity in the

first way and not in the second. Starting from a quantity of capital

leaves no room for valuation effects or distributional conflict in

explaining the wealth ratio *W/Y.* instead, Piketty is

forced to explain the ratio by focusing on the increase in the capital

stock attributable to saving (*s*) relative to the growth

of income (*g*). The problem is, these variables don’t do

much empirical work in explaining the data. Almost all the historical

action in the wealth share is in the changing value of existing wealth,

not the pace at which new wealth is being accumulated.

Piketty’s second law states that in the long run, the ratio of the

capital stock to national income converges toward the ratio of the

savings rate to the growth rate. This second law is the equilibrium

condition of a “zeroth law” (Yanis Varoufakis’ coinage), which says that

the change in the capital stock from one period to the next is equal to

the output from the previous period that is saved rather than consumed.

(Minus depreciation of the existing capital, but Piketty somewhat

idiosyncratically defines saving as net of depreciation, a choice that

has been criticized.) This zeroth law is usually implicit, but it is

critical to the question of whether we should treat capital as a

physical stock. If a value is stable over time except for identifiable

additions and subtractions, we can usefully treat it as a physical

quantity, whether or not it “really” is one. If we assume that the

evolution of the capital stock follows this zeroth law (i.e. that

capital is cumulated savings) and also assume that savings and growth

rates change slowly enough for the capital stock to fully adjust to

their current values, then the capital output ratio will converge to the

value given by Piketty’s second law. [^17] This apparatus – which is

basically the growth theory of Harrod and Domar via Solow – is Piketty’s

preferred tool for analyzing changes in the capital share over time.

So the question is, do these laws describe the historical trajectory of

the wealth ratio? The answer is pretty clearly no.

Piketty, I should be clear, poses this question clearly – not so much in

the book itself, where the Harrod-Domar-Solow framework is mostly taken

for granted, but in articles like this

[one](http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/PikettyZucman2014QJE.pdf)

(with Gabriel Zucman). There they ask: How much of the variation in

alpha and beta – over time and between countries – can be explained in

terms of cumulated savings and income growth rates – that is, by

treating capital as a physical stock? Unfortunately, the answers are not

very favorable. Piketty’s critics on the left have not done ourselves

any favors with our fondness for deductive proofs that any use of

“*K*” is illegitimate. But it is true that, applied

historically, this method can only explain that part of the variation in

income and wealth distribution that corresponds to different rates of

accumulation relative to output growth. And the problem is, most

historical variation is not explained this way, but precisely by the

features Piketty abstracts from – changes in the flow of output going to

owners of existing capital claims, and changes in the valuation of

future capital income.

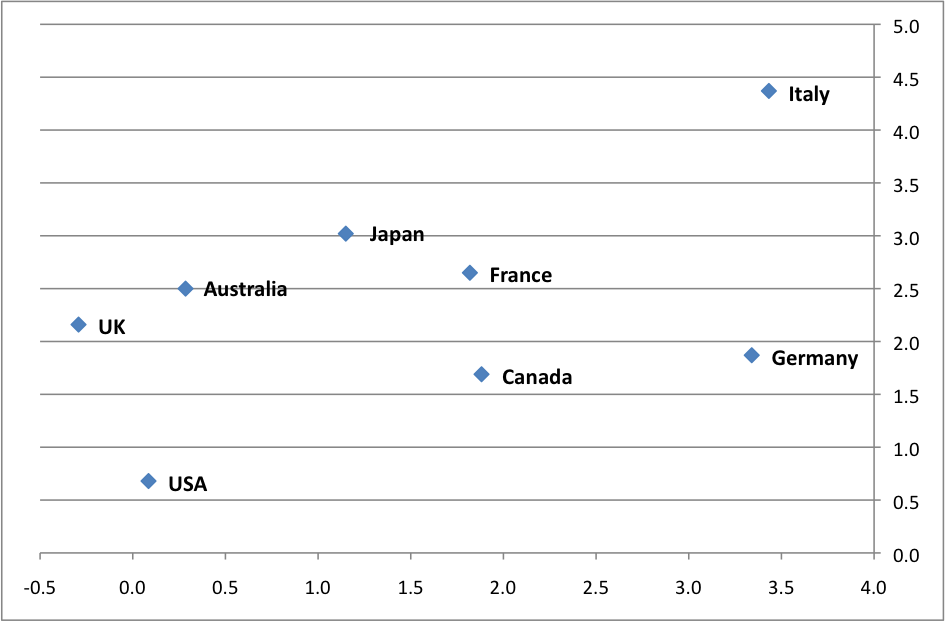

There are many ways to see this. Here are a couple of examples, using

data from his online data appendixes. [^19] First, let’s look at the

change in the wealth ratio *beta* in various countries

since 1970. This rise in the value of capital relative to current output

is one of the central phenomena Piketty wants to understand, and

underlies his claims about the increasingly skewed distribution of

personal income. The horizontal axis shows the change in the wealth

ratio implied by observed savings and growth rates. This is the change

in wealth ratios that can be explained by differential accumulation and

growth. On the vertical axis is the actual change.

As you can see, there is not much of a relationship. It’s true that

slow-growing, high-saving Italy has the biggest increase in the

wealth-income ratio, just as the capital-as-quantity approach would

predict, and that fast-growing, low-saving United States has the

smallest. But that’s it. German savings have been nearly as high as

Italian,and German income growth nearly as slow, yet the growth of the

wealth ratio there is close to the bottom. In the UK, the behavior of

savings and income growth implied that the wealth ratio should decline;

instead it rose by over 200 percentage points. Cumulated savings and

growth rates explain only about 20 percent of the variation in wealth

ratio increases across countries; 80 percent is explained by changes in

the value of existing assets. If we want to know why the capital share

has increased in some countries so much more than others over the past

40 years, the Harrod-Domar-Solow approach is not much more helpful than

the principle of buoyancy would be to analyze the flight performance of

different aircraft.

Next let’s look at the evolution of the US wealth ratio over time. The

second figure shows the historical path of the US capital output ratio

and two counterfactual paths. The counterfactuals are what we would see

if wealth followed the “zeroth law.” The first counterfactual simply

shows the wealth ratio under the assumption of standard growth theory

that the value of capital stock in one year is equal to the value in the

previous year, less depreciation, plus saving. All of Piketty’s formal

analysis is based on the assumption that, on average, this is indeed how

the capital stock behaves. The second counterfactual is based on capital

gains fixed at their average for the full period, and again historical

savings rates. (It also follows Piketty by treating quantity changes as

saving, but this is not qualitatively important.)

What do we see? First, the cumulated-savings trajectories are quite

different from the historical trajectory, even over the long run. As

Piketty notes, the Harrod-Domar-Solow approach assumes that over the

long run, the value of assets rises at the same rate as the price level

in general. But in the US (as in other countries), this is not the case

– over the full 140-year period, real average capital gains are 0.6%

annually. This might seem small, but over a long period it has a

decisive impact on the trajectory of the wealth ratio. As the figure

shows, in the absence of these capital gains the US wealth ratio would

follow a clear downward trend, from a bit over 4 times GDP in 1870 to a

bit less than 3 times GDP today. In the US, in other words, the growth

of the capital stock through net saving has consistently been slower

than the growth of output. Under these conditions, the

Harrod-Domar-Solow framework predicts a declining wealth ratio.

The capital-as-quantity framework also does not fit most of the

medium-term variation in the wealth ratio. True, it does match the

historically observed rise in the wealth ratio during the 1930s and the

fall during World War II, which are driven by changes in the denominator

(GDP) not the numerator. But it suggests that the only significant

postwar recovery in the wealth ratio should have come in the 1970s, when

in fact the wealth ratio reached its nadir in this period. And the more

recent rise in the wealth ratio has come in a period when Piketty’s

framework would predict a sharp decline. During the decade before the

Great Recession, savings were low but capital gains were high; in a

Harrod-Domar-Solow, framework, that implies a decline in the value of

wealth relative to output. The message of Piketty’s data is clear: If

“capital is back,” it is entirely because of an increase in the value of

existing assets, not, as the book suggests, because accumulation has

been outpacing growth. [^20]

So treating capital as a physical stock fails to capture either the

long-run trajectory of capital-output ratios or the variation in wealth

ratios across countries and between different periods. All of the

developments Piketty describes in his historical material, is driven by

the valuation changes that he abstracts away from in his formal

analysis.

With a moment’s reflection, this should not be surprising. After all, a

significant fraction of the wealth stock is land, which is not produced.

If land prices did not consistently rise faster than the general price

level, then land would have long since declined to a trivial fraction of

total wealth. The problem land poses for Piketty’s story is emphasized

by Matt Rognlie among others, whose critique of the book is in some ways

parallel to the argument I’m making here.

If we can’t make sense of the changes in the wealth ratio by thinking of

the incremental accumulation physical stock of capital, how else can we

think about it?

Let’s go back to Piketty’s First Law. As I suggested, there are

different ways to interpret this accounting identity. We can think of it

as Piketty and most other economists do, as saying that there is a stock

of capital goods; these goods generate a certain amount of output, which

is received as income by the owners of the capital goods; that stream of

income can then be compared to the national income to find the share of

capital owners. From this point of view, the stock of capital is the

real sociological fact and the shares are secondary. Alternatively,

instead of starting from an endowment of capital goods, we could start

from the process of social production. The output of this process is

then divided up according to various socially recognized claims, which

we call wages, profits, taxes, and so on. Some claims are marketable;

these claims will have a price. The price of profit-type claims on

output is related to the flow of income assigned to them by

*r*, now understood as the discount factor applied to an

income stream rather than the income generated by an asset.

It’s the same identity, the two stories are formally equivalent. The

effort to turn this formal equivalence into a substantive identity – to

reduce money values and distributional conflicts to the technical

problem of allocation of scarce resources – have yielded two centuries’

worth of tautological circumlocutions. But at the end of the day we are

left with a choice of ways of looking at the same observable phenomena.

In the orthodox perspective favored by Piketty, we ask “why is there

more capital than there used to be?” and “what is the product of each

unit of capital?” In the second perspective – which following Perry

Mehrling we might call the money view – it’s the distribution among

rival claims that is the real sociological fact, and the value of these

of claims as “capital” that is an after-the-fact calculation. From this

point of view, the relevant questions are “how much of the output of the

firm is appropriated through property claims?” and “what value is put on

each dollar of property income?” In which case, we should expect to see

higher wealth ratios not in times and places where cumulated savings

have outpaced growth, but in times and places where the bargaining

process has shifted in favor of holders of capital claims, and where

financial markets place a higher value on ownership claims relative to

current output.

What does this mean concretely? Piketty himself gives some good

examples. There is a short but interesting section in the book on the

abolition of slavery in the US. Here we have a drastic (though

short-lived) reduction in the wealth ratio and capital share in the US.

Clearly, this has nothing to do with any change in the pace of

accumulation of physical capital. Rather, what happened was that a share

in output that had taken the form of a tradable capital-type claim

ceased to be recognized. Piketty presents this as a special case, an

interesting excursion; he might have done better to treat it as a

signpost to the main road. Slavery is only one possible system in which

which authority over the production process, and a share of the surplus

it generates, goes to the holders of particular kinds of property

claims.

Another, perhaps more directly relevant case, is the case of Germany.

Germany, by income one of the richest and most equal countries in

Europe, has among the lowest and most unequal household wealth. In

addition – and not unrelatedly – German corporations have unusually low

stock market valuations. Among the major rich countries, Germany

consistently has the lowest Tobin’s q – shares of a company with given

assets and liabilities are valued less in Germany than elsewhere. The

first puzzle, that of low and highly skewed market wealth, is largely

explained by low levels of homeownership in Germany. Compared with most

other rich countries, middle-class Germans are much more likely to be

renters. This does not mean that their housing is any lower quality or

less secure than in other countries, but it does mean that the same

physical house in Germany shows up as less market wealth.

The lower valuation of German corporations also reduces the apparent

wealth of German households. And why are German firms valued less by the

stock market? Piketty and Zucman offer a suggestive explanation:

> the higher Tobin’s Q in Anglo-Saxon countries might be related to the fact that shareholders have more control over corporations than in Germany, France, and Japan. … Relatedly, the control rights valuation story may explain part of the rising trend in Tobin’s Q in rich countries. … the “control right” or  “stakeholder” view of the firm can in principle explain why the market value of corporations is particularly low in Germany (where worker representatives have voting rights in corporate boards). According to this “stakeholder” view of the firm, the market value of corporations can be interpreted as the value for the owner…

In other words, one reason household wealth is low in Germany is because

German households exercise more of their claims on the business sector

as workers rather than as wealth owners. Again, this is treated by

Piketty as a sideline to the main narrative. But given that almost all

the rise in wealth ratios is explained by valuation changes, this sort

of story about the strength of shareholder claims under different

institutional arrangements probably has more to say about the actual

evolution of the capital share than the whole apparatus of growth

theory.

When I’ve made this argument to people, they’ve sometimes defended

*Capital in the 21st Century* by saying that we should take

its title seriously. Despite appearances, this is not fundamentally a

book about the historical evolution of wealth and income in various

countries, but about what we might expect to happen in the future. But

it seems to me that our interpretation of the historical record is going

to shape our judgements about future prospects. In Piketty’s story,

there seem to be two different kinds of forces at work. There are

valuation changes and revisions of property rights, which operate

episodically; these explain the mid-20th century declines in the wealth

ratio and capital share. And there is the ongoing dynamics of

accumulation, which operates all the time; this explains the convergence

of the wealth ratio and capital share to high levels both in the 19th

century and more recently. (Or explains the increase of the wealth ratio

without limit, if you prefer that reading.)

When we split things up this way, it’s natural to base our predictions

for the future on the continuous process, rather than on the

historically specific episodes – especially if those episodes all

coincide with major wars. The continuous process, furthermore, implies a

tight link between growth and the wealth share. The same acts of saving

and investment that allow society to increase its material production,

also ensure that an increasing share of that production will be claimed

in the form of capital income, even while the great majority of us

continue to depend for our income on labor. So it’s futile to try to

change the distribution of income directly; all that can be hoped for is

redistributive taxes carried out by the *deus ex machina*

of a global state.

But when we realize that changes in the value of existing assets are

central not just to the decline in wealth ratios in the mid-20th

century, but to their whole evolution – including their rise in recent

decades – then the mid-20th century decline no longer looks like a

special case. It’s bargaining power, it’s politics, all the way down.

The same kind of redistributive projects – the decommodification of

basic services like healthcare, pensions, and education; the increased

bargaining power of workers within the firm – that were responsible for

the fall in the capital share in the mid 20th century were responsible,

in reverse, for its rise since 1980. In which case we can learn as much

about our possible futures from the 20th century decline in the claims

of property over humanity, as from their recent reassertion.

[^17]: I’m emphasizing the “zeroth law” here, but it’s worth noting that

the conventional practice of treating s and g as “slow” variables

and beta as “fast” is also open to question. If you look at the

historical data, national savings and growth rates are much more

variable than the capital-output ratio, and they don’t appear to be

stationary around any long-term average. So it seems a bit

nonsensical to talk about the capital-output ratio as converging to

a long-run equilibrium defined by a fixed s and g.

[^19]: Piketty’s presentation of his data online is superb, both in

content and organization. Even if the book were otherwise worthless

– which is very far from the case – these appendixes would be a huge

contribution.

[^20]: Another problem is that Piketty’s narrative suggests that

*r*, the rate of return on capital, is constant or

increasing, while his data unambiguously show a long-term decline.

As a result, the rise in the wealth ratio has not been accompanied

by a rise in the capital share, at least not everywhere. In the UK

and France, there is a clear downward trajectory from a capital

share of 40 percent in the mid-19th century to around 25 percent

today.

{ 75 comments }

Bruce Wilder 12.15.15 at 2:23 pm

Remarkably clear and jargon free. Are you sure you are a real economist?

Zamfir 12.15.15 at 2:50 pm

Yeah, kudos for this. It’s the finger exactly on the sore spot.

MisterMr 12.15.15 at 3:02 pm

I like a lot the OP’s explanation, however there is a question:

– Let’s say that the wage share is somewhat arbitrary and determined politically;

– But then “r” also is arbitrary and determined by – what exactly?

Then “total wealth” depends both on the wage share and r, two arbitrary coefficients.

We end up with two questions instead of one.

PS. a nitpick: While it’s true that Italy is slow-growing, this is true mostly from 1990, so that from 1970 to 1990 Italy grew faster than the USA, while from 1990 to now Italy grew more slowly, but still if we look at the 1970-to-now time window I think Italy grew silghtly faster than the USA (in terms of hourly productivity).

reason 12.15.15 at 3:19 pm

I just checked the contributors and you are not on the list, not that I haven’t been an admirer of yours. Is this a guest contribution or are you joining?

reason 12.15.15 at 3:20 pm

Oops

I see it is a part of the Book event – wasn’t clear from the start.

Matthias Gralle 12.15.15 at 3:27 pm

Great explanation, it made the difference between physical capital and monetary capital, and why this difference is so important for evaluating the historical evidence, crystal clear for a non-economist.

I think much confusion could have been avoided from the outset if P. and other people used functions instead of equations to state their claims:

alpha=f: r,beta->r*beta

vs.

K=f: alpha,Y,R -> alpha*Y/r

Then you clearly see the implicit assumptions about what is independent and what is dependent.

reason 12.15.15 at 3:42 pm

“In other words, one reason household wealth is low in Germany is because German households exercise more of their claims on the business sector as workers rather than as wealth owners..”

Maybe. But maybe there are other factors at work – for instance a larger proportion of savings beings in the form of statutory contributory pensions, and much stricter regulation of borrowing. Asset prices are driven to some extent by the amount of funds chasing the assets.

Layman 12.15.15 at 3:43 pm

Forgive a Layman’s question, but it strikes me as unlikely that wage growth – income derived from labor – can exceed g over the long run. Is that not the case? If not, how not?

William Timberman 12.15.15 at 3:43 pm

Is it really the case, I wonder, that Piketty was unaware of the lacunae in his narrative? No doubt his interpretation in C21 of the data he and Saenz have accumulated — at least as I understood it — skirted the question(s) raised here and elsewhere. In my reading, though, it seemed that he was setting a sort of trap for the masters of conventional wisdom.

If my data are correct, he seemed to be saying, and the current trends are what that data imply they are, do we not have a problem? Moreover, if my solution to that problem is politically impossible, then what would a politically possible solution look like? Isn’t there a sort of neo-Marxian seduction implicit in this formulation? Hasn’t he in fact been anticipating J.W. Mason’s (and others’) criticism — or am I attributing more subtlety to his presentation than the evidence merits?

William Timberman 12.15.15 at 3:46 pm

…data he and Saez… Apologies for the misspelling,

reason 12.15.15 at 3:48 pm

Mr Minute

“but still if we look at the 1970-to-now time window I think Italy grew slightly faster than the USA (in terms of hourly productivity).”

Now you have confused me. Do you mean hourly productivity in manufacturing (which I understand) or some more general measure of productivity (which I’m not sure we can measure). Because it matters a lot, because the relative size of the manufacturing sector might be changing.

reason 12.15.15 at 3:51 pm

Layman @7

What do you mean by long run? Of course any fraction that grows faster than the total will run into a limit at some stage (capital income as well). But for substantial periods of time, it is possible that a share increases.

Bruce Wilder 12.15.15 at 3:51 pm

WT @ 8

He doesn’t have to be a master manipulator, just a well-practiced veteran of the academic circuit, with long experience of what sells among the tribe known as the econ.

MisterMr 12.15.15 at 3:52 pm

@Layman 7

As long that the wage share of total income is less than 100% wage growth can be fater than g, by eating into profits, no?

At some point wage growth has to track g because wages cannot be more than 100% of income obviously, but what is the minimum, or the correct, profit share? Who knows really?

Rakesh Bhandari 12.15.15 at 4:04 pm

Yes, very stimulating post.

How well does s/g do in explaining the long-term movements of K/Y?

Piketty is fully aware of Mason’s challenge and presents historical data at different places in the book to meet it. So those Piketty’s pre-emptive arguments will have to be found and carefully engaged.

Now without re-reading the chapter on the capital/income ratio in light of Mason’s important criticism, I remember that Piketty does grant that the UK does not fit in the last half century but tries to show how Japan does (in spite of the bubble and its puncturing) and that the difference between Europe and the US can be accounted over the long term by s/g and (somewhere) the long term evolution of K/Y in 19th c. France is reasonably accounted for by s/g.

It’s not clear to me that if we measure K not by market value but by book value that the broad dynamics of K/Y in Germany is not well-explained by s/g.

Mason writes: “(It’s striking, for instance, that the book does not contain a table or figure comparing r and g historically.)” But see p. 352

In terms of re-writing the first law, I think Michel Husson’s suggestion is the best:

Instead of alpha=r(beta), we could have r=alpha/beta.

That is the form you would need to show that r which drives investment depends on distributional conflict over capital’s share of income and changes in the capital intensity of production. This way we get the bargaining question in the numerator, but do not make the dynamics entirely entirely dependent bargaining power as Mason in his voluntarist theory is doing; the capital intensity of production also conditions the dynamics.

I think Mason will recognize where the first law in this form comes from.

William Timberman 12.15.15 at 4:10 pm

Bruce Wilder @ 8

Yes, as I remember, that was the gist of Yannis Varoufakis’s somewhat uncharitable interpretation — that Piketty was making sure his status as an economic intellect to be reckoned with would remain secure no matter what happened to his argument. Given how he comes across in the interviews, discussions etc., available on the Web, though, my impression is rather that he wanted to avoid seeing his argument marginalized before its implications were firmly embedded in the public discourse.

Layman 12.15.15 at 4:12 pm

“At some point wage growth has to track g because wages cannot be more than 100% of income obviously”

Yes, this is what I meant. When I read Piketty, I recall thinking that the r > g problem seemed intuitively obvious, because I would expect wage growth to normally be less than g, and I’m reasonably sure it has been so for all of my working life. If so, then r > g will certainly increase inequality. What am I missing?

MisterMr 12.15.15 at 4:17 pm

@reason 10

I mean GDP/hours worked.

I got this figure from a paper about the fall of italian productivity, but the paper is in italian:

http://www.biblio.liuc.it/liucpap/pdf/285.pdf

The relevant table is in english and is table 2 at page 6:

[italian]GDP per hours worked as a % of USA

1970->67,4%

1980->76,2%

1995->92,1%

2013->75,6%

Yes I understand that this is a rather non-relevant nitpick but, as I’m italian, from my point of view is important, or at least interesting.

MisterMr 12.15.15 at 4:25 pm

@Layman 16

In theory wage growth “should” be equal to g if the wage share of income is stable.

The problem is that most often economists treat the wage share as technologically determined, hence more or less fixed. Piketty shows that this is not the case.

IMHO a lot of economic theory should be rewritten if the wage share is not fixed, for example the “correct” interest rate makes sense only in case of a corrct rate of profit, that implies a correct wage share. However, I’m not an economist, so I’ll leave this argument here.

reason 12.15.15 at 4:30 pm

MisterMr

My guess is that statistic doesn’t look much different than what has happened to exchange rates over the same time range. As I said, I don’t place much value of economy wide “productivity” measures. Manufacturing figures which are closer to measuring like to like are more meaningful.

Peter K. 12.15.15 at 4:40 pm

Last night saw the first installment of the SyFy channel’s adaptation of Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End. Advanced aliens come to Earth and promise a “new Golden Age” if we don’t ask too many questions. Among the problems they promise to fix “war, famine, inequality….”

MisterMr 12.15.15 at 4:42 pm

@Reason 19

Sorry for the OT

I also think that such measures of “productivity” are very ambiguous, however in the specific case of Italy I don’t think that the xchange rate is the point (at best, as Italy joined the Euro after 1990, this can explain a loss in competitivity not a loss in nominal productivity).

I think that the continuous austerity since the 90s is the relevant part.

Cam 12.15.15 at 4:45 pm

Hello – this is really terrific, thank you.

Awkward question – is this written up anywhere in else in more detail? (Part of it is that I want to learn more. Another part is that I might want to cite this pretty centrally in a piece I’m writing…and I’m not sure if reviewers would be thrilled with a crookedtimber cite. Apologies if this comes across the wrong way.)

David Woodruff 12.15.15 at 5:30 pm

This piece is great. But I want some precedence on the title! How could Prof. Mason have overlooked my obscure blog post from July 2014, complaining that Piketty

(Note: not actually angry, in case it didn’t come through.)

notsneaky 12.15.15 at 5:39 pm

“It’s striking, for instance, that the book does not contain a table or figure comparing r and g historically”

Piketty basically has three, maybe four, data points. And one of them, the US where the increase in inequality has been driven by completely different factors, pretty much contradicts his story. That’s the thing, even if you buy the r-g thing as a theoretical insight (you shouldn’t), as an empirical regularity it’s also very weak.

“It’s bargaining power, it’s politics, all the way down. ”

That’s pretty much my view.

Sandwichman 12.15.15 at 6:20 pm

Masterful critique, Josh. I hope Piketty replies to it.

A bit of a digression on bargaining power. Historically and geographically when the bargaining power of capital is compromised the result is unfree labor — serfdom, slavery, master-servant legislation, anti-combination acts, “right-to-work.” In other words, weak bargaining power translates into strong state-sanctioned coercion. The theory underlying this is Evsey Domar’s channeling V. Kliuchevesky (1970, “The causes of slavery or serfdom: a hypothesis.” J Econ Hist 30[1]:18–32).

Domar? Does the name ring a bell?

JW Mason 12.15.15 at 6:20 pm

Bruce, Zamfir, thanks!

Notsneaky – I was hoping/expecting you would agree. I noticed you made very similar points in the discussion to some earlier posts.

Cam – I’m afraid not. I would like to write up a more formal version of this at some point … but there are a lot of things I would like to write. But, you can find very similar arguments made by Jamie Galbraith and Merijn Knibbe in the Real World Economics Review special issue on Piketty (which I wasn’t aware of when I wrote this last spring, or would have linked to.) And Suresh Naidu is writing something along similar lines, which should be out sometime in the next few months I hope. (This whole post is based on conversations with Suresh.)

notsneaky 12.15.15 at 6:26 pm

Sandwichman, the problem I’ve always had with Domar’s paper is that it sort of describes the “demand for slavery” (on the part of the landowners). That still leaves out the “supply of slavery” or in other words, the costs that landowners have to incur to keep the peasants enserfed – and it matters whether these are “fixed costs” (build a castle) or variable costs (hire overseers), because it could flip the results. Also, institutional path dependence (like in Brenner of the Brenner Debate)

JW Mason 12.15.15 at 6:46 pm

How well does s/g do in explaining the long-term movements of K/Y?

It explains very little of it. For instance, based on s/g we would predict a decline in K/Y in the US since 1980.

Rakesh Bhandari 12.15.15 at 7:23 pm

From the phone. To assess debate we need first to collect P’s evidence for s/g –) K/Y and his attempts to account for what is anomalous even over the long term. He discusses this question in many places in the world and in the book and at many times across history and different publications. It has assessed as a powerful tendency over long periods

A H 12.15.15 at 8:18 pm

I feel like the capital gains story undermines the labor bargaining story a bit.

Specifically, are the capital gains coming from increased expectations of future cash flows due to weak labor, or are they coming from a lower discount rate? And what is the appropriate discount rate to use? Monetary policy that is only indirectly related to wage bargaining becomes important.

Capital gains are weird though, (what is the opportunity cost of capital gains?)

Sandwichman 12.15.15 at 9:26 pm

notsneaky @28

I would agree that Domar’s theory is incomplete in many respects. It’s only elaborated by Domar for a “simple agricultural economy” — which I would take to be more or less equivalent to the friction-less plane in physics (i.e., there is no such thing). I think it is suggestive though and has been fruitfully explored in specific empirical contexts, such as by Barbara Solow (no relation to Robert AFAIK) in relation to the early modern Mediterranean sugar industry.

Peter K. 12.15.15 at 9:33 pm

“So it’s futile to try to change the distribution of income directly; all that can be hoped for is redistributive taxes carried out by the deus ex machina of a global state.”

Is Piketty really saying that? I thought his global tax solution was one possible reform.

And couldn’t one read the historical data as saying that for some combination of reasons, or for no reason, r is usually around 5 and growth is slow, except for the social democracies’ golden age?

But then is Mason arguing, correctly, that there’s no basis to predict the future? Is Piketty really that pessimistic about the future or is he more open minded. One can be pessimistic about the trend but then follow that up by saying things aren’t set in stone.

Rakesh Bhandari 12.15.15 at 9:46 pm

AFAIK, Barbara Solow was the wife of Robert Solow, and will prove to have made a more important contribution to social scientific knowledge than her husband.

T 12.15.15 at 10:17 pm

JW — What do you make of the fact that the wage share of income declined across the board in both developed and developing economies? http://conversableeconomist.blogspot.com/2013/06/labors-falling-share-everywhere.html

Trader Joe 12.15.15 at 10:24 pm

I’d like to simply add my praise for this particular article. It was very well written and was easy for an educated lay-person to follow.

I’m not sure I’m qualified to poke holes or assert alternatives, but I guess my reading of it suggests that these explanations fit the data a whole lot better than Picketty’s conclusions do and as such, seem to point to materially different policy prescriptions than the ones which Picketty’s supporters would want to promote.

As has been observed on other threads within this series, it seems like the singular benefit of Picketty’s work is to provide a fairly obtuse set of data and conclusions which can be subverted to favored policies, regardless of whether the work supports those polcies or not. This work provides a better read of the data – time will tell if the conclusions gain their own appropriate level of bargaining power within the discourse.

Rakesh Bhandari 12.15.15 at 10:28 pm

@29 First, this is a single example, which then raises the question of its probative value in relation to the examples adduced by Piketty (Japan from 1970-2010 in spite of a bubble, comparison of Europe and the US over the long term in terms of s/g, the rise of K/Y in 19th century France being well accounted for by s/g,).

Second, Piketty clearly himself emphasizes what Mason writes here: “Cumulated savings and growth rates explain only about 20 percent of the variation in wealth ratio increases across countries; 80 percent is explained by changes in the value of existing assets.”

Piketty (p. 173) himself carefully argues that much of the explanation for the rising wealth ratio in the last forty years is due not to s/g working its way out but to the privatization and transfer of public wealth into private hands in the 1970s and 80s (esp crucial for the UK, see also p. 187 for Eastern Europe) and a long term catch up phenomenon affecting real estate and stock prices.

Now I cannot find immediately the proportion of the K/Y increase in, say, the last forty years that Piketty thinks these two factors account for, but it is substantial, so what Mason is saying is roughly what he himself says, more or less, with his own regressions, to boot! Again I think a careful reading of the capital/income chapter will reveal Piketty more than willing to grapple with the difficulties that his beta equation runs into.

At any rate, it will be interesting to see how Piketty responds to the Mason/Galbraith/Varoufakis criticism.

Sandwichman 12.15.15 at 10:43 pm

Rakesh @34,

Thanks for that. I just checked. You are right.

Bartholomew 12.16.15 at 12:00 am

Re Barbara Solow and family – an article by her on Eric Williams and slavery has one of the all-time great acknowledgements:

“I would like to thank my sons, Andrew R. and John L. Solow, for assistance in producing the mathematical results, and my husband, Robert M. Solow, for assistance in producing the sonsâ€.

notsneaky 12.16.15 at 12:08 am

To add, Barbara Solow’s stuff on slavery really is excellent and pretty comprehensive. I thought she was a historian though not an economist.

JW Mason 12.16.15 at 3:15 am

Sandwichman-

My buddy Suresh Naidu — conversations with whom were the origin of this post — made the same Domar connection in his Jacobin piece on Piketty.

JW Mason 12.16.15 at 4:45 am

David Woodruff-

I’m sorry to say I hadn’t seen your blog before. (There’s a lot to read, on the internet.) But I definitely will be looking at it in the future.

Sandwichman 12.16.15 at 5:23 am

Josh,

Fantastic!

christian_h 12.16.15 at 5:56 am

Late to the party, so let me just join in thanking Josh for an extremely enlightening post.

LFC 12.16.15 at 7:38 am

Still sort of working my way through the post — I do grasp the main points, well most of them — and I’m not going to say anything substantive. But just from the standpoint of terminological clarity for the lay reader, when the post gets to the 9th paragraph or so — the explanation of the first chart/graph — it would help if the choice of language reminded the reader of the basic point that the ‘wealth ratio’ is the ratio of ‘capital stock’ (or wealth) to national income (i.e. GDP). So this passage:

would be a clearer, imo, if it read (suggested changes in italics):

A layperson reading quickly and late at night sees the phrase “wealth-income ratio” and may not immediately grasp what the phrase means here, which is why I suggest these minor changes — should you ever decide to expand this into a bigger paper or something.

Lei Gong 12.16.15 at 8:03 am

May not be qualified to offer critique here, but I’m not entirely sure your reformulation of Picketty’s first law is complete. It seems that by reconfiguring the first law from the standpoint of endowments to that of social production, you’ve discarded any quantification of endowments (either their amount or their performance) as a component independent of social production in determining capital shares. I think Rakesh in post 15 captures this problem best when he points out that

“Instead of alpha=r(beta), we could have r=alpha/beta.

That is the form you would need to show that r which drives investment depends on distributional conflict over capital’s share of income and changes in the capital intensity of production. This way we get the bargaining question in the numerator, but do not make the dynamics entirely entirely dependent bargaining power as Mason in his voluntarist theory is doing; the capital intensity of production also conditions the dynamics.”

TM 12.16.15 at 10:05 am

An accurate and crystal clear demystification of the r>g business. Thanks, and congrats. (And also, btw, exactly what I’ve been saying).

engels 12.16.15 at 10:45 am

Don’t let it go to your head, JW.

Peter T 12.16.15 at 11:20 am

This is very clear. It chimes with my own, much less well-expressed, thoughts. Perhaps one could link the confusion of capital (the physical means of production) with wealth (the value of claims on income) with Ann Cudd’s post on the Normative Force of Wealth Inequality. It can’t quite be bargaining power all the way down, because that would lack any legitimating justification. Re-casting wealth as capital (and capital as the result of frugality) offers that justification.

engels 12.16.15 at 12:04 pm

OT but on the normative issue I’m coming round to the view that there doesn’t need to be any ‘legitimating justification,’ all that’s needed is a way of fobbing off particular people with particular criticisms at particular times. If such justifications collapse under sustained scrutiny, perhaps that’s not important, or only in the Keysean long-run.

Bruce Wilder 12.16.15 at 10:00 pm

WT @ 16: in my mind, I keep coming back to Paul Krugman’s note on Piketty, On Gattopardo Economics, where he offered his opinion that neither Piketty’s work nor a concern about inequality as a problem for political economy required overturning the neoclassical approach of mainstream economics. Krugman praised Piketty’s conventionalism:

Then, Krugman turns and snarls:

Snarl over, Krugman then put his mask of supreme reasonableness back on.

That remarkable defense by Krugman for muddle-headed thinking as long as it is conventional, neoclassical and “convenient” struck me as revealing of his stubborn adherence to the conventions that make mainstream economics a tool of conservative ideological legitimation and obscurancy, but maybe is also a measure of just how heavy a lift Piketty faced, to use Brad Delong’s piquant phrasing. If you can only engage Krugman on these extreme concessionary terms, maybe Piketty’s discretion concerning which battles to fight is sensible. Krugman would seem to be one of the easy ones, after all; if you can’t get Krugman, who could you get? Better to be regarded a fool, than ignored entirely.

Bruce Wilder 12.16.15 at 10:11 pm

The production function maybe seems an esoteric’s gateway into that labyrinth of algebra and calculus, where economists take the unwary for a magical mystery tour of mystification and helpless confusion. As Henry says in one of the other Posts, “Standard economic arguments start from an implicit set of assumptions about the absence of power relations.” Well, the production function embodies those politics-stripping assumptions.

William Timberman 12.16.15 at 11:22 pm

Bruce Wilder @ 16

Yes, I suppose my semi-fictional narrative of a Piketty who employs the skillful means of a Zen Master to subvert the status quo is more than a little lame. My only defense is that subversion by design makes a more dramatic story than subversion by accident. On the other hand, the latter might serve us well enough in the end, depending on who and how many can be persuaded that something must actually be done.

I probably shouldn’t bet on it, though. If Krugman’s rush to hide the silverware is any indication, what we’re more likely to wind up with is yet another one of those sickly just-so stories, tainted with the same kind of wishful thinking that made rabid Obama supporters out of people who damned well ought to have known better. If so, what remains for an old leftie except to tuck his Wobbly card back in his shirt pocket and head on down to the pub.

Rakesh Bhandari 12.17.15 at 12:49 am

@51 See http://www.potemkinreview.com/pikettyinterview.html, beginning with “I do not believe in the basic neo-classical model.” Krugman does not have Piketty right on this question.

JW Mason 12.17.15 at 3:17 am

Rakesh,

That’s a very nice interview. I had meant to link to it in the post.

For present purposes the key part is:

Which is consistent with William Timberman’s story. It’s also incidentally very much like the relationship of the original Capital to Ricardo.

And then a bit later he says:

So of course he’s aware of the kind of argument made by Varoufakis, Galbraith, Knibbe, and me in this post. I probably should have made it clearer, my goal here was not to take an “anti Piketty” position, but to show how little his (IMO very substantial) contributions depend on the whole apparatus of s, r and g. Now, to what to extent he adopted that apparatus as a kind of immanent critique of orthodoxy, and to what extent because he thinks it’s genuinely useful in organizing positive claims about the world, I couldn’t say.

Rakesh Bhandari 12.17.15 at 4:06 am

I think you and Sneaky Not are not right about how much Piketty’s argument depends on that whole apparatus.

When he tries to show that the movement of α can be explained in terms of what he claims to be a reasonable estimate of the marginal rate of substitution, he is working within the neo-classical framework.

But I don’t think is whole apparatus is such an immanent critique. I want to see whether we can agree on what it is.

g likely falls from 3 to 1.5%

then β rises (say s remains 10%, so β goes from 333% to 666%)

and r-g rises because after-tax r stays roughly constant at 5% due to useful robotization, increased capitalist power and lower taxation;

then we will

have a rising α or rβ or capital share of income (which would go in this example from 16.6 % to 33.3%):

and an unequal rentier society will emerge out of the petit-rentier one we have.

The emergence of an actual rentier society depends on the difference between r-g rising and stabilizing at a new level.

Of course if r fell in proportion with g, then alpha would at the least not increase.

r must be greater than g, and the whole dystopian dynamic depends on the difference between r and g stabilizing at a new higher level.

Eventually the system will reach a steady state as a rentier society if there is not revolt along the way (Piketty reminds his readers that rentier society on the even of the Great War engendered retrograde nationalism as a way to unify a divided nation and violent frustration–see also Bukharin’s critique of rentier society; Keynes would later hope for the euthanasia of the rentier). Piketty expects backlash. Perhaps Piketty thinks he has fired an even more dangerous missile at the head of the bourgeoisie than Marx claimed he had; after all, Piketty has better statistical technology.

The problem with Piketty’s theory is not his insistence that the widening of the difference between r and g plays a crucial role in his theory–I think this discussion has been very misguided; it is his supposition that that s and r will not decline in the course of accumulation. But Piketty is aware of the problems here–see here his piece in JEL.

Piketty could have more easily freed himself of the supposition of declining marginal returns on capital had he built on the basis of the Cambridge Capital theory, but he is probably right that s will not decline by much as wealth accumulates as consumption will represent, if anything, a smaller share of an enormous capital income.

LFC 12.17.15 at 4:14 am

It’s also incidentally very much like the relationship of the original Capital to Ricardo.

A point that does not appear to have been fully grasped by Marx’s recent biographer, the historian J. Sperber: see Karl Marx: A Nineteenth-Century Life (2013), ch. 11, “The Economist,” esp. p.462.

Rakesh Bhandari 12.17.15 at 4:21 am

Where in Capital I chs 4-6 and 21-23, Marx argues that property laws that were meant to said to secure the fruits of one’s own labor become the framework to own in objective form the the appropriated labor of others, he is engaging in an immanent critique not of Ricardo but Locke. I would love to talk about Piketty’s opening chapter on Ricardo, Marx and Kuznets.

JW Mason 12.17.15 at 4:21 am

Yes, Rakesh, I understand the logic. My point is that this kind of story does not, in fact, explain the variation in the wealth-to-GDP ratio or capital share historically.

r stays roughly constant at 5% due to useful robotization

This assumes that r reflects the marginal product of physical capital. Otherwise robots have nothing to do with it.

JW Mason 12.17.15 at 4:25 am

(that’s in reply to 56.)

Rakesh Bhandari 12.17.15 at 4:34 am

In the example I gave from Ian Steedman useful robotization either maintains or increases the available surplus while putting capital in a good position to appropriate at least the same share of it. r is not being technically set by the marginal physical product of capital. There are no marginal physical products in a Sraffian framework, the same framework Samuelson used to try to rid the world once and for all of the labor theory of value.

Give the data over the last forty years that you tested, Piketty had already agreed with you that s/g was not always the major factor in the increase and in the variance in wealth/income ratios. But once we account for privatization and the long-over due reduction in the risk premium, the effect of s/g shines through as an explanation for Europe’s higher ratio than the US’s, the rising wealth-income ratio in Japan even after the bubble was punctured, and in the rise of the wealth/income ratio in France in the 19th century. He does at least have some data going his way!

Rakesh Bhandari 12.17.15 at 3:53 pm

So if savings are not used for real capital accumulation but rather for speculation in real estate and stock markets, then in real terms the K/Y would not be rising; but would such a bout of speculation also raise the capital share of income? It could due to the wealth and credit effects generated by asset bubbles that profits and the capital share of income rises as well (Akerlof and Shiller consider such a dynamic in their Animal Spirits).

So here we would have a fun house mirror of Piketty. Yes due to asset inflation it appears that K/Y is rising with s/g and that all this is resulting in a rising capital share. It would seem that Piketty’s laws are holding. Beta is rising due to a higher s/g; and alpha rises as a result of the increase in beta.

But in fact the rise in K is a rise in nominal values only; and one of the reasons g is low is in fact due to weak real capital accumulation.

If this is the story J.W. Mason is telling, I would not rule it out. It’s an old Marxist story of course–see Henryk Grossman, 1929. What channels savings into a frenzied bidding up of the prices of assets in real estate and stock markets rather than into real investment is of course a drop in the profitability at the margin of new capital accumulation.

Will Boisvert 12.17.15 at 5:58 pm

“So treating capital as a physical stock fails to capture either the long-run trajectory of capital-output ratios or the variation in wealth ratios across countries and between different periods….With a moment’s reflection, this should not be surprising. After all, a significant fraction of the wealth stock is land, which is not produced. If land prices did not consistently rise faster than the general price level, then land would have long since declined to a trivial fraction of total wealth.”

I wonder about this in the case of land. In the sense of land as a productive capital asset, it might indeed make sense to view it as a “physical stock” that increases over time.

Take the semi-arid land of California’s Central Valley. It used to be almost worthless as farmland. But with irrigation systems, tractors, fertilizer, rail lines and roads and trucks to ship out the produce, it has become some of the most productive farmland in the world. We can straightforwardly measure that increase in capital value as a “physical stock” quantified in bushels per acre. We could equivalently think of the increased fertility as the production of new land–the creation of many new Central Valleys to grow food on.

So how do we account that increase in bushels? Doesn’t it make sense to think of it as an increase in landed capital as a physical stock? Or should we think of it as the return on capital invested in irrigation and transport? Should we chalk it up to the factor productivity of fertilizer? Or impute it all to increased labor productivity of the farmer?

Bruce Wilder 12.17.15 at 7:16 pm

Rakesh Bhandari

Let me say that I have appreciated your impressive command of the Piketty oeuvre, including interviews and commentary supplementing the text of the Big Book, and the perspective and sense of proportion and context that it has allowed you to share.

Rakesh Bhandari @ 62: So if savings are not used for real capital accumulation but rather for speculation in real estate and stock markets, then in real terms the K/Y would not be rising . . . a rise in nominal values only . . . What channels savings into a frenzied bidding up of the prices of assets in real estate and stock markets rather than into real investment is of course a drop in the profitability at the margin of new capital accumulation.

The tyranny of the neoclassical model derives from the potent hold deep metaphors that contrast the “real” with the supposed maya of money, as if money were this veil that shrouds “what is really going on”. There’s a not very subtle theme in the neoclassical model — which the Krugmans fiercely deny but never eschew — of virtue magically driving the operation of the system and it weaves together with this distinction between the real and the nominal.

What’s hard to grasp is that the economy is not a morality play, even though economics is a moral science. The institutional economy is the only economy that exists and the institutional economy provides a kind of virtual reality where money is how we move the game pieces and keep score. There’s no social behavior outside that virtual reality created by institutions, even if there are real consequences.

The ex ante organization of production that we refer to as real capital investment is mobilized by money in flows of funds and the score-keeping of credit. And, if there is any income to be drawn out of ex post output, it is because the rules of the game have been successfully manipulated to permit earning an economic rent. The so-called stock of capital, however virtuous its enhancement of productivity, draws no natural income independent of the political rules and business models that find an economic rent in exclusion and coercion. That economic rents represent an opposition of private power to social good just points to how inescapably problematic is the loosely coupled economic activity of an economy that features so much hierarchy, uncertainty and displacement of risk.

The distribution of income isn’t well-characterized by rates of flow alone, because the distribution of income in its full regalia as motive power is the distribution of risk. That bigger piles of money earn higher rates of returns than smaller piles of money “savings” is a clear tip-off that risk and insurance, not accumulation of a productive stock per se, is key.

otpup 12.17.15 at 8:41 pm

BW @64 “real†with the supposed maya of money,

It occurred to me the other day that talking about money/finance and “the real economy” was akin to talking about the nervous/endocrine systems and “the real body”.

A H 12.18.15 at 5:04 pm

“The distribution of income isn’t well-characterized by rates of flow alone, because the distribution of income in its full regalia as motive power is the distribution of risk. That bigger piles of money earn higher rates of returns than smaller piles of money “savings†is a clear tip-off that risk and insurance, not accumulation of a productive stock per se, is key.”

This supports a Piketty like mechanical process of inequality over a political one like Mason is proposing. Also it should that focusing on aggregate wealth is misleading if the returns on capital are different along the wealth scale, in the US the bottom quarter probably is probably close to zero or negative net financial income.

Bruce Wilder 12.18.15 at 6:16 pm

A H @ 66

If it wasn’t otherwise clear, I am with Mason: it is about bargaining power all the way down.

The bargains we strike are contingent ones, in which the distribution of risk shapes behavior, and is meant to shape behavior. The archetypal employment contract: “I’ll pay you a fixed wage to do what I tell you to do, and if you don’t do it, you’re fired.” features such a contingency. Its effectiveness depends on how costly to the employee it is to be fired and how productive, within the employer’s production organization, it is to be obeyed. The employer has the legal and political power to exclude the employee from access to that productive organization of resources — the means of production, as it were — and probably also to make a take-it-or-leave-it offer of employment as well as to fire the employee “at will” or pursuant to some process under the employer’s sole control (e.g. binding arbitration).

This is the basic outline of the bargaining context, and though its fairness or unfairness may be the thing to first strike a casual reader, the economic theorist will notice that the employer-employee relationship is a political one: not just an isolated exercise of power to arrive at a deal in this one instance, but to enter into a continuing relationship where the employee is a functioning part of a social organization exercising political power in the economic system. I am not talking about influencing the legislature when I say, political; I am talking about the daily routine of operating a business using an extensive, hierarchically supervised team of strangers to accomplish tasks and administer technical control a production and distribution process — that’s politics in action in daily life.

Treating capital as if it is a stock and can be usefully regarded as an accumulating stock in a broad range of circumstances is deceptive I think without making the bargaining explicit. The production function model is particularly faulty, because it assumes away the managerial and technological, even while pretending that capital qua stock can earn an income proportional to marginal contribution to output, as if it is being metered into the production process. As I said elsewhere, capital investment tends to consist at its core of sunk-cost investments. There’s no metering into output; no varying with quantity of ex post output. And, being a sunk-cost investment the historic cost of the capital itself cannot demand or bargain for an income. Its sunk, its done. If there’s a bargaining power, that bargaining power is attributable to the political rules of the game and the entrepreneur’s manipulation of them. Wealth earns an economic rent, and that rent is a political arrangement semi-detached from the particular characteristics of the sunk cost “stock” of capital. Contingency enters it, though, and the struckness of a sunk-cost investment may make it a cornerstone of persistent structure and risk-bearing.

Stripping out the politics of uncertainty and risk robs capital of its functional essence.

A H 12.19.15 at 3:38 am

“Wealth earns an economic rent, and that rent is a political arrangement semi-detached from the particular characteristics of the sunk cost “stock†of capital. ”

And then since it is a capitalist system we are talking about, these political arrangements can be bought and sold in financial markets. Regardless of the underlying political process which created these claims, holders of more wealth will have a higher capicity to purchase arrangements with higher risk and earn a higher rate of return over time.

LFC 12.20.15 at 2:09 pm

Ze K @69

of course politics is a mere manifestation of the present form of social consciousness, based on what they call “social relations of productionâ€

Are you perhaps aware that the famous passage about ‘relations of production’ and ‘social consciousness’ is not the only thing Marx wrote that might bear on the matter? (And even if it were, that wdn’t nec. make it correct.)

It’s a reactionary book

Then why the **** is CT devoting so much time to it? Riddle us that. Dare one ask what non-reactionary bk you think CT should be discussing instead?

Bruce Wilder 12.20.15 at 4:37 pm

A H @ 68: holders of more wealth will have a higher capicity to purchase arrangements with higher risk and earn a higher rate of return over time.

I am not sure how “higher risk” should enter the narrative, if we are striving to speak honestly and plainly. As you imply, it may not be a higher risk in a large enough portfolio. And, we ought to consider strategic span of control — if you buy up competitors and antagonists, you may have additional options to corrupt the institutional processes that force wealth to bear risk.

LFC @ 70

I think Ze K is right: it is a reactionary book in that its acceptance of neoclassical economic terms of reference abstract so far from reality that people have to be reminded that the distribution of income is contested politically.

But, it is a useful book in that the absurdities of its overarching framework combine with its nod to Marx to invite such reminders even while engaging the complacent and exposing the conventional wisdom to at least a cursory examination. This very mild form of slightly subversive controversy is CT’s specialty.

Rakesh Bhandari 12.20.15 at 4:42 pm

Branko Milanovic, American Prospect:

“Piketty has returned economics to the classical roots where it seeks to understand the “laws of motion†of capitalism. He has re-emphasized the distinction between “unearned†and “earned†income that had been tucked away for so long under misleading terminologies of “human capital,†“economic agents,†and “factors of production.†Labor and capital—those who have to work for a living and those who live from property—people in flesh—are squarely back in economics via this great book.”

Alex K. 12.20.15 at 9:50 pm

“capital investment tends to consist at its core of sunk-cost investments

[…]

Wealth earns an economic rent, and that rent is a political arrangement semi-detached from the particular characteristics of the sunk cost “stock†of capital.”

I’m genuinely interested in a fleshing-out of this theory of rent as a result of sunk-cost investment.

John Investor makes an investment in some real capital assets — a sunk cost investment. As a result of ex-ante shrewdness and ex-post luck, that investment earns rents higher than the rate of interest.

The claim that seems to be made here is that those rents are fair game to be distributed by a political process, without much in the way of a negative consequence for growth in general.

But what about the other two investments made by John Investor, the sunk-costs investments that actually lost money? How does this magical process work, where just by virtue of having liquid assets, you can be sure to make sunk-cost investments that on average earn rents?

Indeed, if such a magical process existed, then we could easily solve all economic problems: just have some worker’s fund chase all those easily obtainable rents and distribute the proceeds to those workers.

Again, I do want more detail on what Bruce Wilder means, as this seems to be central to a lot of claims that he makes in this forum. So far, it does not look like a defensible theory.

Bruce Wilder 12.21.15 at 2:36 am

Alex K

Abstract terms of reference have their hazards, as you demonstrate.

You have made an argument made familiar in the doctrine of contestible markets: that John Investor is a portfolio investor taking risks with his liquid capital, making multiple wagers, some of which pay off big and some of which may prove losers. From John Investor’s point of view what motivates his risk-taking is the ex ante expectation of return on all his bets taken together. Ex post, a high return on one particular lucky bet may look excessive, but the big win ought to be seen in the context of having made several bets, some of which proved to be losers. Assuming there was social value to the trial-and-error, it would be policy short-sightedness to begrudge John Investor a high return in one case when that big win merely offsets losses, resulting in a merely average return on the whole portfolio.

That particular highly stylized case delineates one aspect of business investment, but is abstracting from many aspects of what is a dynamic process in which political power and negotiation plays a prominent part.

I am saying a business, to survive, has to find a business model where it has the political power to earn a return on sunk cost investments. To understand the significance, you have to understand that merely making a useful investment does not guarantee the ability to charge enough to earn back the invested amounts.

Consider an extreme example: investing in a railroad in the mid-19th century. Before a railroad business can operate, it must have rail laid along a route where it has a right-of-way, terminals, locomotives, rolling stock and trained personnel. Just building the rail along the route was an enormously costly venture, and it had to be completed before transportation services could be sold. Of course a completed railroad could move a lot of people or goods very quickly compared to the previous alternatives: horse-drawn wagons or canal boats, and in many cases at a much reduced cost. The implications for farmers, merchants and manufacturers along the route of reduced cost of transport were clear.

So, imagine the railroad from London to Manchester or Philadelphia to Pittsburg has been built and gone into operation: what rates can that railroad charge? Will the railroad charge a flat rate of some sort — so much per pound or per volume measure? Will the railroad be able to earn a return on its investment and pay its fixed costs from what it earns from operations?

Building the railroad has changed what it costs to travel from Manchester to London or to move merchandise from Philly to Pittsburgh. But the sunk cost investment in rail and route is no part of that new cost, because the sunk cost investments can not be withdrawn. When the merchant or traveller comes to the railroad to “negotiate” a rate or ticket price, only the variable costs of operating a train have to be covered to induce the railroad to want to accept an offer. But, if the railroad does not charge someone more, the railroad will never earn a return on investment.

It becomes an intensely political issue. The railroad can make or break a merchant or farmer, by its rate setting. Rates determine the value of land along the route. For scheduled services in particular, railroads need to be able to price discriminate, but no one wants to be the one paying extra.

Political power was necessary to get a right of way. Governments granted eminent domain. Political power was necessary set discriminatory rates. Land grants were used to aid financing of railroad construction.

Workers on the railroad were among the most productive in the society. But, they needed effective unions to achieve pay commensurate with that productivity and government set rules for labor relations, as rail unions discovered their hold-up power.

Established companies, which have at least partly solved the problem of earning an economic rent are in a privileged position in being able to be relatively certain in their prospects for being able to secure returns on later and further investments. The most powerful railroads could invest at low risk in reducing the cost of their own operations.

Rakesh Bhandari 12.22.15 at 4:39 am

From the OP: “The same identity could be read in other ways, for instance, K = alpha Y/r. Formally this is the same but it means something different. It means that a certain share of output is first claimed by a class of capital owners, and then their tradable claims on this income are assigned a value based on a discount factor r.”

I don’t understand how the r is determined in this formulation. I still suggest the best way to read the identity is r=α/β.

This means that as beta tends to rise as a long term tendency due to a new higher s/g, capital can only maintain its rate of profit by tilting the distribution of income in its favor.

r is now clearly not just a marginal product of capital. It depends on distributional struggle; this formulation puts distribution in the center.

This makes the bargaining question even more important for the normal operation of capitalism than it is in Mason’s rewriting of the first law while still not making social dynamics only about bargaining.

Who first wrote the identity as r=α/β?

Rakesh Bhandari 12.22.15 at 3:59 pm

Again I think it is too subjectivist to make the value of the capital stock almost entirely dependent on fluctuations in extant capital values themselves dependent on bargaining power reflected in alpha.

I like Mason’s old point that with technological progress the value of net additions to the capital stock tend to decline in value. If this is true the savings that need to be invested for net additions for the capital stock would tend to fall.

And this creates problems for Piketty because s/g may adjust downward and beta may not rise and thus the capital share would not have to rise dangerously high to keep r constant.

This line of criticism has always been the most important one against Marx as well.

Comments on this entry are closed.