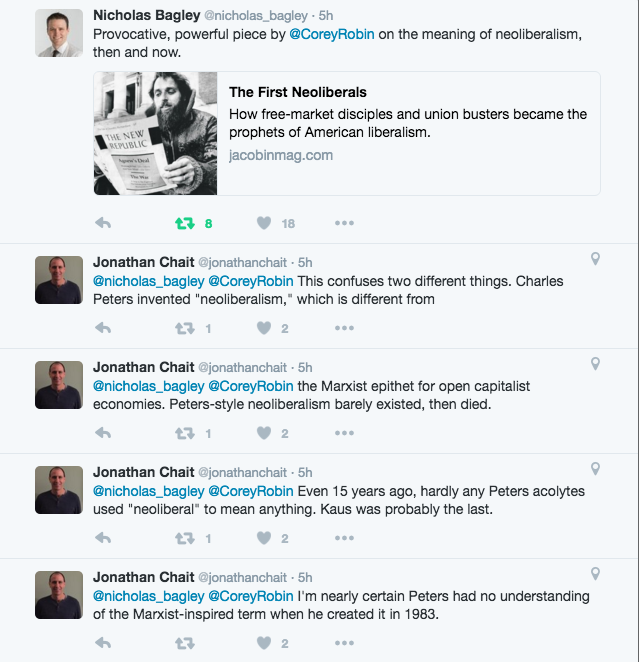

My post on neoliberalism is getting a fair amount of attention on social media. Jonathan Chait, whose original tweet prompted the post, responded to it with a series of four tweets:

The four tweets are even odder than the original tweet.

First, Chait claims I confuse two different things: Charles Peters-style neoliberalism and “the Marxist epithet for open capitalist economies.” Well, no, I don’t confuse those things at all. I quite clearly state at the outset of my post that neoliberalism has a great many meanings—one of which is the epithet that leftists hurl against people like Chait—but that there was a moment in American history when a group of political and intellectual actors, under the aegis of Peters, took on the name “neoliberal” for themselves. That’s who I was talking about in my post.

Second, contrary to Chait, Peters did not in fact invent the term “neoliberal” or “neoliberalism” in 1983. The term was coined by a group of mostly conservative free market intellectuals, meeting in Paris in 1938 at the Colloque Walter Lippmann, in order to counter the rise of democratic socialism and welfare-state liberalism in Western European and the United States. Eventually, that group would coalesce after World War II as the Mont Pelerin Society, with Friedrich Hayek at the intellectual helm.

Third, the reason that earlier coinage matters, and isn’t just a point of scholarly pedantry, is that while some scholars will challenge what I’m about to say, the program that that original group of neoliberals set out at Mont Pelerin does in fact bear a resemblance to the word “neoliberalism” that often gets bandied around by the left today. Insofar as that was a program to rollback the welfare state and social democracy, to revalorize capital and the capitalist as a moral good, to proclaim the ideological supremacy of the market over the state (the practice is more complicated), “neoliberal” is in fact a useful term to describe a political program that has gained increasing traction around the globe in the last half-century.

It’s important to distinguish neoliberalism in this sense—that is, neoliberalism as a political program—from neoliberalism as a system of political economy. Scholars and activists on the left disagree, fundamentally, about the latter, with some claiming that what we call neoliberalism as a form of political economy is merely capitalism. I’m deliberately side-stepping that debate in order to focus on neoliberalism as a political and ideological program.

(It’s also important to acknowledge that one of the reasons the term “neoliberalism” can be confusing is that outside of the United States, particularly in Europe, liberal has often meant support for free markets and a critique of the welfare state and social democracy. Inside the United States, liberal, at least throughout most of the 20th century, meant support for the welfare state and state intervention in the economy. Get into a discussion about neoliberalism on Twitter, and you inevitably find yourself crashing on a beachhead of this confusion. Personally, I think it’s about as interesting and relevant as that Founding Fathers fanboy who’ll periodically pop up in a discussion thread claiming that the United States is a republic, not a democracy. I merely note it here in order to acknowledge the point and move on.)

Fourth, insofar as Peters and his group of neoliberals in the United States declared the fundamentals of their political program to be: a) opposition to unions; b) opposition to big government (except for the military); and c) support for big business, I find the term “neoliberal” to be useful not only for describing Peters and his crew but also for relating that crew to the overall program of neoliberalism, which I noted in point 3 above, and which today characterizes a good part of the Democratic Party. In other words, while I deliberately did not conflate Peters’s neoliberalism with the leftist epithet for Democrats that Chait objects to, there is in fact a relationship between Peters’s neoliberalism and today’s Democrats (more on this below).

(Incidentally, if you think I was being unfair to Peters-style neoliberalism, I urge you to read this interview Peters gave to Ezra Klein back in 2007, where he reiterates the basics of the program as I outline them here and in my post, and says, forthrightly, “I think in many, many areas, the neoliberals, in effect, won.” That is, they changed liberalism (again, more on this below.) The only plank of the original program that Peters thinks needs to be pursued more forcefully is crushing teachers’ unions and means testing mass entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare.)

Fifth, the inspiration for my post, as I said, was a tweet from Chait in which he takes particular delight in professing an impish disbelief in the term “neoliberal,” as if it were a made-up word of paranoid leftists used to abuse liberals like Chait. And in this series of tweets, he doubles down on that disbelief, claiming that Peters-style neoliberalism had at best a shadowy half-life in the magazine world; it “barely existed,” tweets Chait, “then died.” No one’s used the word in ages.

In my post, I claimed that one of the reasons contemporary writers like Chait write from this state of amnesiac euphoria—where they fail to recognize the distance they’ve traveled from the midcentury world of labor liberalism—is that they’ve so completely absorbed the neoliberal critique, almost unconsciously, that they can’t even remember a time when liberals thought otherwise.

It turns out that that wasn’t quite fair. There was a journalist back in 2013 who recognized precisely what I was talking about. Here’s what this writer said about the impact of neoliberal magazines on traditional Democratic Party liberalism (h/t the guy whose Twitter handle is HTML Mencken):

Those magazines once critiqued Democrats from the right, advocating a policy loosely called “neoliberalism,” and now stand in general ideological concord.

Why? I’d say it’s because the neoliberal project succeeded in weaning the Democrats of the wrong turn they took during the 1960s and 1970s. The Democrats under Bill Clinton — and Obama, whose domestic policy is crafted almost entirely by Clinton veterans — has internalized the neoliberal critique.

The name of that writer was Jonathan Chait.

Update (6:30 pm)

I was just re-reading the introduction to The Road from Mont Pelerin, which I link to above (and which I highly recommend), and the authors claim that the first usage of “neoliberal” along the lines of what I mention above was actually by a Swiss economist in 1925 (there was actually a 1898 usage as well, but they claim it was rather different). In the 1930s, neoliberal took off as a term, particularly in France, culminating in that 1938 meeting that I mention above. As the Cornell historian Larry Glickman pointed out to me in a Facebook thread, the term neoliberal was also used by anti-New Dealers in the United States in the 1930s, only their point was to stress that FDR had transformed liberalism from its 19th century understanding (an understanding that was much more sympathetic to markets) into a “neoliberalism” that was too critical of the market and indulgent of the state’s intervention. According to the authors of the introduction to The Road to Mont Pelerin, Frank Knight, a close associate of Milton Friedman and George Stigler at the University of Chicago, wrote an essay criticizing the New Deal in the 1930s along these lines.

Update (9 pm)

Jonathan Chait has a longer response on his Facebook page. It’s kind of a non-response response that I’m posting here merely for the sake of, whatever. More amusing to me is how Damon Linker—think of him as Mark Lilla’s Mini-Me—shows up faithfully in the comments section, like one of the Super Friends in response to a summons from the Bat Signal. Anyway, here’s Chait:

I wrote a tweet a few days ago complaining about the use of “neoliberal” as a term of abuse on the left against liberals. “What if every use of ‘neoliberal’ was replaced with, simply, ‘liberal’? Would any non-propagandistic meaning be lost?,” I wrote. My meaning is that no current group of people defines itself as “neoliberal.” The term is simply used by leftists, usually of the Marxist and/or socialist variety, to denigrate liberals.

Corey Robin has fired back in two posts. None of them, however, answer my question. The first post focuses on a small sect on intellectuals called “neoliberals,” a term that was invented by Washington Monthly editor Charles Peters in the early 1980s. Neoliberalism was not really an ideology (though Peters sort-of tried to flesh it out into it) but a collection of Peters hobbyhorses that mostly revolved around streamlining the functioning of the federal government. Some writers tried to take other aspects of moderate liberalism and call it “neoliberalism.” But the main point is that the label died years ago, and nobody uses it any more as a form of self-identification. Importantly, even though elements of its ideas made their way into the Democratic Party, the label also never attracted any real following in the Democratic mainstream. Bill Clinton, probably the closest thing to an ally neoliberals would have found, called himself a “New Democrat.”

I was never a fan of the “neoliberal” label, for reasons that were persuasively explained to me by Paul Starr when I worked at the American Prospect out of college. Neoliberal writers called their farther-left counterparts “paleoliberals.” As Starr told me, the terms were an attempt to win an argument by using an epithet — “neo” implying that its side had already won the future, and “paleo” implying the other was consigned to the past.

That debate was consigned to a handful of writers (most of them baby boomer men from the Washington Monthly and the New Republic of the 1980s) who passed from the scene or lost interest in it. Modern liberals are all just liberals, though of course we have internal differences. Robin does not refute my point that no current faction uses the label to describe itself. Instead, in his follow-up post, he notes that some right-wingers also used the phrase in the 1930s to oppose the New Deal. To a leftists like Robin, this proves that the ideology is all one and the same. “Insofar as that was a program to rollback the welfare state and social democracy, to revalorize capital and the capitalist as a moral good, to proclaim the ideological supremacy of the market over the state (the practice is more complicated), “neoliberal” is in fact a useful term to describe a political program that has gained increasing traction around the globe in the last half-century,” he writes.

And, yes, if you believe that Charles Peters took his inspiration from the anti-New Deal right, and the modern Democratic Party took its inspiration from Peters, then that is an important connection. But the first connection is preposterous. Peters was a New Dealer who worshipped Roosevelt. He did not see himself as an heir to the 1930s Old Right. Peters was much less a statist than Robin, but clearly belonged on the left half of the political spectrum throughout his career.

Of course, it is convenient for Robin to lump the center-left, with figures like Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, in with the far right. This was all Robin’s ideological foes, those who stand for somewhat higher taxes and more generous social spending and decarbonization and regulation of finance can be lumped together with the conservatives who wish to roll all those things back.

So obviously Robin and many of his allies will continue to use the term “neoliberal” to describe liberals, because it serves an important propagandistic function for them. But it will continue to be used only by those people to describe current politics, and by nobody else, because it is not a neutral term or a fair-minded attempt to describe the world.

{ 246 comments }

Priest 04.29.16 at 9:55 pm

The referee needs to stop the fight.

Placeholder 04.29.16 at 10:15 pm

My favorite part is how he still doesn’t actually even try to prove it’s a Marxist term.

“In fact I’ve read every Marxist essay quoted in this piece, some of them multiple times”

– https://twitter.com/jonathanchait/status/725732709881004033

An he still can’t prove it, but hey, YOUR HATE WILL MAKE IT REAL. How neoliberal.

bob mcmanus 04.29.16 at 10:16 pm

The problem for me is making the connections between Hayek, Friedman and Mont Pelerin on the one hand and eventually Clinton, Krugman, and Obama on the other hand while keeping neoliberalism as a specific historic political program with certain covert consequences (for instance hierarchical as you have discussed in some posts). Yes indeed, if you say Hayek = Obama same thing, you will get pushback from the centrists and moderates.

So I have to abstract from the history and programs and describe neoliberalism as something like “the ideology of the use of political power for individualistic purposes” thus including bank bailouts, title nine, the ACA. And of course looking globally at for example the nearly simultaneous repression of labour power on four continents I can only see neoliberalism as the emergent political economy of late capitalism.

Layman 04.29.16 at 10:19 pm

“In fact I’ve read every Marxist essay quoted in this piece, some of them multiple timesâ€

He is aware of all the Marxist traditions.

William Berry 04.29.16 at 10:33 pm

” . . . that Founding Fathers fanboy who’ll periodically pop up in a discussion thread claiming that the United States is a republic, not a democracy.”

LMAO. Heard Chuck Todd on MSNBC the other day actually say something like: “I sometimes like to remind people [when they complain about the arbitrary absurdities of the U.S. electoral system] that the United States is a republic, not a democracy.”

So, not just Founding Fathers fanboys, but puffed-up, self-important political pundits as well.

Why do some, presumably intelligent (benefit of the doubt and all), people have so much trouble wrapping their heads around the concept of a “democratic* republic”?

*For a range of values of “democratic”, obviously.

Cranky Observer 04.29.16 at 10:33 pm

Personally I don’t see the value in trying to connect a 1930s European concept of neoliberalism with a deliberately designed and implemented US movement of the 1970s/80s. Were there sources and influences? Possibly. And as an academic blog possibly more posts on that topic are of value – after the 2016 election and HRC’s selection of her cabinet. But at this moment Chiat is laying down covering fire for those of WJC’s team who hope to make a triumphal return to power and resume punching to the left/down (not saying that HRC agrees), and he well knows that.

DaveL 04.29.16 at 11:15 pm

Surely the fact that various political pundits and politicians and even (gasp!) economists used the same term as a way of saying “liberalism has gone astray” means that they all mean the same thing and propose the same program of reform is a rather bold leap. Even in academia, the same word can be construed to mean different things; in political discourse, not so much.

Placeholder 04.29.16 at 11:50 pm

https://www.facebook.com/JonathanChaitPublic/posts/1256997364327888

Jonathan has now climbed down from saying neoliberals don’t exist and its all a COMMIE FLUORIDE PLOT to whining about how its unfair people think he’s got anything in common with the right just because all the smart people at the new republic supported the iraq war. And carbon taxes.

Jon, that’s what makes you a neoliberal.

kidneystones 04.30.16 at 12:02 am

Hi Corey. Thanks for this, your follow-up is much appreciated and for me much sharper than the original, especially with your update.

You and others here err egregiously only in your assumptions that Chait and other champions of new liberalism give a shit about historical and intellectual accuracy. The entire “new liberal” edifice as it is structured both in the US and in other western democracies is nothing more than a rationale for grasping self-interest. It’s a two-fer for the upwardly mobile class exemplified by Elizabeth Warren, Bill, HRC, and the Obamas. Ivy League connections provide social cache (of a sort) and entry into the world of real money. Warren flipped houses for fun and profit during the great real estate scam we’re all paying for now, while building her cred as a native American legal eagle champion of the poor (true!). Why shouldn’t she get in on the fun? Michelle convinced Barry to cozy closer to Tony to get that amazing Hyde Park property while Tony’s tenants froze with no heat in Chicago.

“Nobody told me!” Is the constant mantra of the new liberal and the concerned conservative (essentially the same person), so the NYT can write op-eds about the

‘unseen poor’ well into the Obama years and Brooks can now discover that ‘hey’ life outside the semi-elite enclaves where six-figure earners gather to lament the rising costs of private schools and ‘good help’ isn’t really all that great after 8 years of new liberal rule.

New liberalism justifies class social climbing at the expense, primarily, of the richest who are expected to provide the cash to keep the lower orders content in public housing, etc, whilst new liberals race to distance themselves from the folks they profess to love, in order to become in every material sense as close to those they profess to hate.

In short, they suck.

JeffreyG 04.30.16 at 12:24 am

Chait dislikes the use of ‘neoliberal’ because it sounds to him like a dismissive slur rather than an accurate characterization of his ideas. Of course, Chait himself employs ‘Marxist’ in precisely this manner, so this sounds to me more like a matter of projection than principle.

kidneystones 04.30.16 at 12:45 am

The consequences of new liberal bullshit are manifesting themselves now even as Chait whines. http://www.salon.com/2016/04/29/a_liberal_case_for_donald_trump_the_lesser_of_two_evils_is_not_at_all_clear_in_2016/

The core assumption of modern New liberalism is that the greatly increasing number of people lower down on the food chain must learn to content themselves with less and less in a world where globalization and outsourcing are irreversible, and where their concerns and fears are increasingly viewed as meaningless and inconsequential.

For some reason, however, the poor are listening to David Brooks and Jon Chait. In fact, those in fly-over country are every bit as incensed at the hubris, frankly, of CT-type lefties, obscenely rich we know best GOP elites, and other sneerers, as Sander’s supporters. Because, I suspect, so many CT readers and commenters are far closer to Chait in their practices than they’d comfortably acknowledge (Bruce Wilder being a notable exception). Many of the geriatric self-satisfied here are blissfully unaware of just how bad things are for young people. The result is the Salon piece linked, and others, that question whether Trump may well be the better candidate.

This is Salon we’re talking about for fuck’s sake. Not the NRO. The NRO remains vehemently opposed to the Trump candidacy. Even as the tectonic plates shift (or appear to shift) people here are lost in discussions about definitions of neo-liberalism, and yet seemingly ignore how forcefully American voters are rejecting new liberal practices by Democrats many here profess to reject, but will support in the voting booth in November.

It’s a free country (at present). But if any think voters watching protesters force Trump to crawl under fences, smash police cars, and silence free speech on campus are winning over the majority of voters, many of whom have not had a pay raise in 18 years, I’d suggest that assumption needs a re-think. There is no room for nationalism and patriotism in the ethos and world-view of the moral minority. Both are anathemas to some.

That’s not the case, however, for people losing their jobs across America to outsourcing and legal immigrants entering America on visas allowing companies to profit while American workers suffer. The NYT, HRC, new liberals in general, and the GOP have demonstrated repeatedly they couldn’t give a rat’s ass how many Americans lose their jobs and guess what? Americans have finally noticed. Worse for you, is the fact that they now have a champion who has the resources, the rhetorical skills, and the will to set fire to the status quo.

Thousands gathered to protest the Trump rally in Orange County. Cue clapping. A car was flipped and a Trump supporter bloodied-up. Woo-woo. The 31,000 highly-motivated Trump supporters inside the arena noted every scream and epithet leveled at them.

Independent Americans, many of them tax-payers born in the US and naturalized citizens listened as they were abused as ‘racists, bigots, fascists’ etc for demanding strong borders and legal immigration. I’m sure each and every Trump supporter savored and drank the entire experience in. Millions more Trump supporters watched the news and will relive the experience either at Trump rallies across America, or in social media.

There’s a revolution taking place in America today – and it’s a rejection in many respects of many of the most closely held assumptions of new liberalism. Whether Trump can succeed in overturning the old order is a different question. But make no mistake, when magazines like Salon are raising the question of Trump’s appeal to Sanders’ voters at a time when 13 percent of these voters already regarding Trump favorably, new liberalism is under attack.

Colin Danby 04.30.16 at 12:54 am

Accepting that the term has multiple births, one connection is Latin American. The term was well enough established in 1982 for Alejandro Foxley to write his 1982 _Experimentos Neoliberales en América Latina_

http://www.cieplan.org/media/publicaciones/archivos/125/Capitulo_1.pdf

in which he traces it to the “monetarist” side of the monetarist/structuralist controversy of the 1960s, and emphasizes key features that emerged in Chile post-Pinochet, in particular emphases on financial liberalization with an open capital account, and the argument that sweeping market liberalizations would lead to macro growth.

The obvious points are that there are links between the Mont Pelerin Society and the Chilean economists, and in turn to numerous U.S. economists with like interests. John Williamson’s canonical 1990 “What Washington Means by Policy Reform” is basically this program, and you can see in his references some of the key players.

I don’t see any *direct* connection between this work and Charles Peters’ crude screed, though. Peters refers to a 1982 Esquire article by Randall Rothenberg as his source for the term. I can’t find the full article online, but a Kirkus synopsis calls it “a commitment to industrial policy–a policy of directed investment, principally through tax policy, to spur economic growth via new technology and new markets–that also entails cost-effective military reform, increased science teaching and technological training, labor/management cooperation rather than confrontation, and some notion of compulsory national service” which is definitely not Latin American neoliberalism. It seems to be the half-baked 80s centrism of people like Gary Hart.

Robert 04.30.16 at 1:12 am

I like some of Chait’s work. I think he is somewhat more intelligent than, for example, Wolf Blitzer. (I recall Blitzer on Jeopardy.)

I’ve been rereading the Mirowski and Plehwe book myself. I like to note the existence of this reference:

Milton Friedman (1951). Neoliberalism and Its Prospects.

Friedman begins Capitalism and Freedom (1962) by whining about how the term “liberalism” does not mean anymore what it meant in Manchester in the 19th century. He does not begin Free to Choose (sic) that way.

And, I guess, we are now into discussing Friedman’s hero, Pinochet.

kidneystones 04.30.16 at 1:42 am

Josh Marshall is finally demonstrating what a Brown doctorate in history combined with a conscience can produce. I apologize for implying that the academic discussion of neo-liberlism here is deficient because it fails to acknowledge the rise of Trump’s nationalism and America firstism as a consequence of new liberalism. I’m excitable, I confess. Normally, Marshall and his writers editorialize to provide an anti-GOP spin and minimize Dem deficiencies, as he should. That’s the function of the site. The last week, in particular, has seen a real shift in the balance of the content.

I’ll close for the weekend with this TPM clip http://talkingpointsmemo.com/livewire/trump-undocumented-people-killed

The TPM is notable for two reasons. First, the principal speaker is Jamiel Shaw, an individual who is likely to feature prominently in Trump’s appeal to Sanders voters, as well as the general public. I watched the entire Orange County rally yesterday. Marshall, to his immense credit, simply lets Shaw tell his own story.

Peggy Noonan, normally a dunce, produced an astonishingly astute piece on Trump. Trump is not running as a Republican, or as Democrat. His FP speech was flawed, but that won’t matter a bit because Trump is as far from an idealogue as can be. Indeed, according to Noonon, Trump is rising because Americans are sick to death of the failures of ideas and ideologies of both parties.

Trump is running as an American. Moreover, Trump is running as an immensely proud and uncompromisingly patriotic American, socially liberal, pro-immigration, fiercely willing to defend American lives, American jobs, and American interests. Trump like Reagan is utterly uninterested in ideas, only solutions for America’s problems. Trump promises to defend and fight for the interests of Americans, rather than for the rights of undocumented workers. Trump promises to impose punitive duties on American companies who choose to relocate outside the borders in order to discourage American job loss. Trump promises to put the interests of all Americans first, and that would be all Americans – the richest and the poorest, those who want to work in coal mines and those who want to work in colleges, Americans who play and live by a nation of laws.

js. 04.30.16 at 1:48 am

Well, that’s a bit like saying, “They’re a better band than Happy Mondays,” no?

——

Re CR’s post: I thought the last post (the Jacobin one) was very helpful, but like several others on this thread, I’m a little confused by the Mont Perelin connection. Without getting into the weeds of the myriad possible meanings of “neoliberalism”, I do think it’s useful to distinguish between right-neoliberalism (which the rest of the world calls “neoliberalism”) and left-neoliberalism (which in the US gets called “neoliberalism”). Mont Perelin would I think fall into the first of these, Peters, Chait etc. into the second. And while there are undoubtedly ideological affinities, and both were perhaps shaped by similar social forces (or rather, one was a kind of reaction to the other—perhaps), I do think they are best considered as distinct phenomena. In other words, “neoliberalism = Mont Perelin and Charles Peters” seems like equivocation (or something close to it) to me.

Ronan(rf) 04.30.16 at 2:34 am

I gaze into the doorway of temptation’s angry flame

And every time I pass that way I always hear my name

Then onward in my journey I come to appreciate

That every banality is numbered, by every Jonathan Chait

Lupita 04.30.16 at 2:48 am

@bob mcmanus

I can only see neoliberalism as the emergent political economy of late capitalism.

… and late Western hegemony.

@kidneystones

I like your term “new liberalism”. It is to neoliberalism as pounds are to kilos.

@Colin Danby

the term has multiple births, one connection is Latin American.

Of course. Debates that ignore this are as disconcerting to me as football games where the ball isn’t even round.

LFC 04.30.16 at 3:24 am

@kidneystones

Trump like Reagan is utterly uninterested in ideas, only solutions for America’s problems.

Too bad Reagan didn’t provide solutions for America’s problems. His supply-side economics and tax cuts — disproportionately for the wealthy — increased inequality; his destruction of the air-traffic controllers union put the admin firmly against (organized) workers and collective bargaining; the Iran/contra scandal was a disgrace; military spending exploded under R.; and he appointed Scalia to the Sup Ct. For starters.

Reagan began his political life as a New Dealer (and, of course, as president of the Screen Actors Guild). When he converted to conservatism, it was for a mixture of reasons, but his conversion came w a full acceptance of the ideological package as expounded in the pages of Natl Review and as preached by Reagan initially for GE.

Reagan wasn’t an intellectual but he was committed to a worldview — a bad, stupid worldview, to be sure, but something probably coherent enough to warrant the designation. I doubt the same can be said of Trump.

phenomenal cat 04.30.16 at 3:39 am

“@Colin Danby

the term has multiple births, one connection is Latin American.

Of course. Debates that ignore this are as disconcerting to me as football games where the ball isn’t even round.” –Lupita @17

Yeah, my initial (and painful) understanding of neoliberalism came from literature on Latin America. So maybe I’m biased, but it’s always seemed to me that if one really wants to understand neoliberalism as an interlocking, multi-scaled, programmatic political and economic phenomenon then one only need accost the first Latin American one sees on the street. They’ll fill you in.

It’s obvious Chait has no knowledge of the political and ideological history that informs the term. None. As someone said upthread, it’s just a bad word sanctimonious leftists spit at reasonable people–like shithead or something.

Anon 04.30.16 at 4:04 am

@15 ” ‘I think he is somewhat more intelligent than, for example, Wolf Blitzer.’ Well, that’s a bit like saying, ‘They’re a better band than Happy Mondays,’ no?”

Odd analogy. Everyone knows who Blitzer is, only a declining population of aging hipsters knows the Monday’s. No one thinks Blitzer is a paradigm of intelligence, but a whole generation of UK critics think they’re geniuses. They’re all right if overrated, while Blitzer’s dumber than jello.

js. 04.30.16 at 4:12 am

All right, it was a dumb joke. I could have said Creed or Pearl Jam or whatever, but in the moment, Happy Mondays seemed like a funnier choice. (Also, loads of UK critics think they’re “geniuses”? Seriously? That does not ring true to me, but I admit I could be wrong.)

Ronan(rf) 04.30.16 at 4:23 am

For my own part, I wouldn’t go as far as say they were geniuses, but an inspiration at least, in some respects. None musical.

Anon 04.30.16 at 4:23 am

Oh, it wasn’t really meant as a criticism, just honestly found it surprising. Never saw what the big deal with the Happy Mondays was, so interesting that someone thought they were unimpressive enough to stand in for “as bad at music as Blitzer is at smart.” Kind of refreshing, really. That in the day UK critics loved them was my impression, though I don’t know if their reputation has held up. (I do seem to remember that 24 Hour Party People was pretty hagiographic, but that’s getting pretty old now too)

Philip 04.30.16 at 8:49 am

Anon @ 20 by everyone I think you mean all Americans as in the UK the Happy Mondays are far better known than Wolf Blitzer. I don’t think the HM’s were seen by anyone as musical geniuses but got a lot of love as they were seen as encapsulating the Madchester scene. I think they are still well regarded as a symbol of what was going on in Manchester and they were never about being great musicians but did make some songs that have stuck in British culture.

David 04.30.16 at 8:50 am

In practical politics, ideas don’t usually become powerful until the powerful find them useful to adopt, or at least expound, and the powerful themselves generally don’t worry too much about ideological coherence anyway. Searching for the intellectual origins of neoliberalism is interesting academically, but doesn’t tell us why such policies were actually adopted at a certain point. The generation of politicians and bureaucrats in power since the end of the Cold War understands that simply saying “We will rob you” to the electorate might go down badly, but that on the other hand spending a tiny percentage of its wealth buying academics, journalists, commentators and politicians to pretend that stupid ideas are sensible ones can have a very high payoff. Sometimes politics is simpler than those who write about it professionally are prepared to accept.

bob mcmanus 04.30.16 at 9:14 am

Lupita: … and late Western hegemony.

Yeah, thank you. One of the reasons I am attracted to the word or concept “neoliberal” is the assemblage of concepts connected to “liberal.”

“Consent of the governed:” in an unit of analysis about who is consenting, and having the various rights attributed to legitimacy (who can effectively speak, who can form associations); and who is coerced, disempowered, delegitimized, abject.

“Those who consent” are constantly engaged in overlapping processes of territorialization, as in the creations of states, but no longer or less importantly geographical but now based on large part on education and skills and affective networks.

It is important to me to move among all the sites of agency: the Foxconn worker is pretty damn abject, but likely has some degree of agency with her dormmates or village family which might be leveraged for resistance to external hierarchies.

The novelty in New Liberalism might have to do with the diffusion and consciousness of that agency, the skills and opportunities to form or join associations by choice rather than contingent circumstances; and the incentives material, social, psychological to do so in ways that reproduce already existing power relations.

engels 04.30.16 at 10:13 am

There’s trolling, and then there’s comparing the Happy Monday to Creed. Wanna to take this outside?

(Fwiw I know for a fact HMs are still pretty popular outside of UK as I was living in a trendy non-Anglophone city a few years ago and hearing them everywhere..)

ZM 04.30.16 at 10:37 am

From Australia neoliberal isn’t a hugely popular term I would say. It is used in academia mostly, where readings usually look at neoliberalism from more than one perspective — the main two being as a normative program or agenda, and as a descriptor of governance changes since the mid 70s or 80s.

One main difference is that Liberal is the name of the non-Labor political party in Australia, so Liberal tends to be opposed to Labor generally, and this is the case since before the neoliberal turn in the 70s. The Liberal Party was named after a meeting called by Robert Menzies, and the idea was the non-Labor parties should unite. This worked pretty well for him, since he ended up being our longest serving Prime Minister. But the name was taken from the Commonwealth Liberal Party which was also formed as coalition of non-Labor parties, in 1909.

In Australia our federal Labor party wasn’t so successful in the post-war years from 1945 to 1980 as the Democrat party in the USA.

In the Post-War years Democrats were the majority of US presidents from 1945 to 1980 (Truman ’45 to ’53 ; Kennedy ’61 to ’63 ; Johnson ’63 to ’69; Carter ’77 to ’81) holding office for about 20 years out of 35 years, whereas in Australia we had fewer post-war Labor governments (Chifley ’45 to ’49 ; Whitlam ’72 to ’75) with Labor forming government only for about 9 years out of the 35 years.

I think that if you were talking about the post-war style of governance, you would not say that Australia had neoliberal governance by the Liberal Party, you would identify Australian governance in the post-war period as similar to that in the pre-Reagan USA and the pre-Thatcher UK.

Similarly we had Labor government from 1983 to 1996 (Hawke and Keating), but this was when economic rationalism became most prominent as the dominant economic ideology in Australia (economic rationalism is our closest word for neoliberalism, and is a term in popular usage unlike neoliberalism) .

So governance in Australia has shown similar turns as that in the USA, but with different sides of politics being at the helm.

I don’t really know where I’m going with this argument exactly, but Australian politics did have what you would call a neoliberal turn but it took place under a 13 year Labor government, whereas our “New Deal” post-war bureaucratic governance era would have been under a (non-Labor) Liberal government for most of the time…

ZM 04.30.16 at 10:39 am

“The Liberal Party was named after a meeting called by Robert Menzies” , I meant to include that this meeting happened in 1944

JPL 04.30.16 at 12:08 pm

Not having been in the US in this period, I was wondering, why did practical politicians, associated pundits and other activists trying to build a movement for the purposes of winning elections for the Democrats (or Labour for that matter) feel that it would be expedient to make like they accepted certain elements of the agenda, and the patterns of justification for this agenda, of the Republicans (or “conservatives” in Corey’s sense), e.g., having to do with the role of “the market”, the role of “big government”, or the approach to problems of crime, etc? It doesn’t seem to make sense from the perspective of trying to construct an explanatory theory of government and economic interactions as consistent with ethical principles rather than the principle of the precedence of power; and doesn’t make sense from a practical perspective, since it involves betrayal of their traditional responsibility of standing up for the workers and minorities on the receiving end of the brutal and callous actions of the powerful. Was it a response to the need to attract big money donors to compete in elections with the Republicans (or Tories)? Were these well-intentioned people who were losing their souls on the way to hell?

Also, let’s not forget the phenomenon focused by Rich Puchalski on the other thread: the system of conventional knowledge, values, standard responses to problems, the “what everybody knows” that never requires reflection or deeper understanding that seems to be held, mostly implicitly and tacitly, by the common “governing class” of the world’s governing institutions. This is a different phenomenon from the above movement- related ideologies, but as Rich says, it’s definitely consequential and has concrete effects. It’s, e.g., the “received wisdom” that was brought so heavily to bear on Greece in their debt crisis. Or the thinking of the cross- administration “foreign policy establishment” that I imagine had to be struggled with to achieve the nuclear agreement with Iran. What precisely are the general principles and values that actually govern the decision- making operations of these institutions? They require scrutiny and making tacit principles explicit, since, again, no doubt they needlessly and mistakenly respect power and disregard the ethical imperatives, and an enlightened people need to be able to say, “That ain’t right!”.

ScrewyCanuck 04.30.16 at 12:21 pm

Let us not forget that in the 80s and 90s, when these New Democrats were gaining control of the Democratic Party in the U.S., ‘liberal’ was a VERY dirty word. This is especially true for ‘third way’ types who wanted to convince those on their right flank that they weren’t like those dirty smelly hippies on the left.

OF COURSE it wasn’t a self-applied term: it went against their branding strategy.

The idea that descriptive labels applied by critics aren’t legitimate is another disingenuous complaint from people like Chait. He wants to reserve the right to come up with something that gives this ideology the intellectual credibility of liberalism without seeming stale, soft-headed, or weak. Having his cake and eating it too, in other words.

Chait remains an enthusiastic hippie-puncher, by the way. I suspect his animus is based on perpetual irritation that his critics on the left refuse to fall in line. The original tweet was just an exercise in trolling.

bob mcmanus 04.30.16 at 12:38 pm

30: Only halfway through it, and I am having some problems, but Thomas Frank attempts to answer your questions in the recent Listen, Liberal

Very short: meritocracy, education, technocracy, professionalization, and consensus as ultimate value. Let me see, I’m skimming: orthodoxy, academics, blindness to predatory behavior if cloaked in credentialed professionalism, insularity: all East Coast Ivy Leaguers, the vast majority lawyers. Differences and conflicts arise from knowledge gaps, cause we are all so rational, you know.

The problem I have with the Frank book is the lack of any mention at all of race, gender, etc. Who is he writing for? Doesn’t he know his reputation, his problem?

Layman 04.30.16 at 12:52 pm

“Not having been in the US in this period, I was wondering, why did practical politicians, associated pundits and other activists trying to build a movement for the purposes of winning elections for the Democrats (or Labour for that matter) feel that it would be expedient to make like they accepted certain elements of the agenda, and the patterns of justification for this agenda, of the Republicans”

I think it was a direct response to the shift of working class whites from the Democratic to the Republican Party, which shift ultimately culminated in the Reagan revolution. The Republican conservative movement tailored their small government message to appeal to white who perceived that large government was being employed to advantage minorities at their expense. Taxes, social programs, redistribution, etc, all became bad large government liberalism, and the strategy was effective enough to bring an end to Democratic control of Congress and doom Democratic Presidential candidates who identified or were cast as ‘liberal”. The DLC and Clintonism – embrace the conservative message and some of their policies – was the response.

bob mcmanus 04.30.16 at 1:12 pm

33: Well, that story is certainly the consensus among identity Democrats.

Frank tells a different story, that the McGovern Commission and those it empowered kicked Unions and the white working class out of the Party 1968-72.

And it really isn’t that Democratic Elites are cynically using Wall Street as a money spigot; the fact is that Wall Street is no longer your grandaddy’s Wall Street, much more socially liberal, and Democrats like the Clintons and Obamas genuinely prefer the company of the Bill Gates and Mark Cubans and Summers and don’t want to have anything to do with the working class or poor.

One of the key demographic changes from over the last generations is the inter-educational marriages, someone with a degree or advanced degree marrying someone high school or less. Yes, it was gendered, but it did happen a lot. No longer happens at all.

ScrewyCanuck 04.30.16 at 1:47 pm

I think the 68/72 elections and the rise of Reagan acted as a one-two punch on liberal elites. The massive defeat of McGovern convinced them that grassroots movements within the party had to be squelched, and the loss of reliable working class voters, who became known as Reagan Democrats, led to the conclusion that the party’s platform had to mimic the Republican’s, in order to win back those voters.

This story does not take into account demographic changes, racial tensions, nativism, etc., but I think elite opinion was more concerned with hearing a tale that could convince them that strengthening their own control over their party was going to solve the problem of electoral defeat.

One further thought: I think that as the generation who lived through the Great Depression, and fought in WW2, aged out of the governing class, a lot of the liberal ethos was lost.

Soullite 04.30.16 at 2:04 pm

[aeiou] It is my fervent dream that at some point, we lay everyone who ever argued, either to themselves or to others, that sacrificing the well being of low-income Americans in order to boost the prospects of the poor in India or Bangladesh, out in a long chain, secured to the ground by posts, and that I will personally be able to go Ghallagher on all of their heads with a sledge hammer.

Those people are traitors, both to their country and to their countrymen, and they deserve to die terrified and bloody. [aeiou]

bob mcmanus 04.30.16 at 2:25 pm

36: But that isn’t really what it is about.

What it is about showed up in a comment over at LGM, something like:

“My brother-in-law made $300,000 doing the SAP for the transfer of the Carrier air-conditioning jobs to Mexico.”

Every transfer of 10 $50k factory jobs overseas creates 2-5 $100k “creative class” jobs ( in services, finance, education, entertainment) back in the USA, and I add, probably 1-2 creative/managerial class jobs in the developing country, to identify under conditions of cultural imperialism with their peers in OECD countries.

This is the intersection of domestic neoliberalism with Lupita’s neo-imperialism

kidneystones 04.30.16 at 2:43 pm

@36 This comment would get you banned at any responsible site. I’ll say good-bye to all now.

Plume 04.30.16 at 2:44 pm

Bob @34,

Frank is frank about Democratic Party realities, and this doesn’t make him popular among “liberals,” who are really just compassionate conservatives these days.

There really isn’t that much difference between them (Dems and Republicans) on economic, war, empire, surveillance issues. Even taxes, which was once a sure-fire point of departure. And because it’s all relative now and PoMod, “liberals” can claim massive differences where they don’t exist, because the bar has been lowered so much. Like the paltry increase at the top from 35% to 39.6%, with even that weakened by making all Bush tax cuts permanent from dollar one to 400K. Weakened further by raising the top from 250K to 400K.

The ethos is basically the same, with different vehicles in place. For “liberal Dems,” it’s education. For Republicans, it’s business, “free enterprise,” etc. etc. That’s the pathway out of poverty or the middle class. Which results in, basically, the Dems catering to the richest 10%; the Republicans to the richest 1%. That still leaves the vast majority of Americans in the dirt, thrown under the bus, kicked to the curb, etc.

I wish America at least had the option of a coalition government that would include an alternative to this: The 100% alternative. No hierarchies to traverse. At least none so steep that they would take lifetimes or several generations. Instead of constantly struggling to move up the ladder, how about no ladder in the first place, and we’re already there, all of us, 100% of us, able to live and let live from Day One?

In short, all of this wasted time — decades, generations, centuries — struggling to find ways to move up the ladder of life. Our time would be far better spent trying to end class distinctions in the first place. End that endless journey up the pyramid. Flatten all of them instead.

Layman 04.30.16 at 2:49 pm

“Every transfer of 10 $50k factory jobs overseas creates 2-5 $100k “creative class†jobs ( in services, finance, education, entertainment) back in the USA, and I add, probably 1-2 creative/managerial class jobs in the developing country, to identify under conditions of cultural imperialism with their peers in OECD countries.”

Um, no. The factory employs people in perpetuity, while the transfer jobs are temporary (it’s a one-time event), and with some frequency even those temporary transfer jobs go to outsourcers using at least some offshore labor.

Layman 04.30.16 at 2:52 pm

“There really isn’t that much difference between them (Dems and Republicans) on economic, war, empire, surveillance issues. ”

Really, this is nonsense. Whatever you think of Obama, the notion that he’s no different a president on these issues than was Bush doesn’t stand up to even a moment’s scrutiny.

michael braverman 04.30.16 at 3:15 pm

Once again, Robin embarrasses himself. Striving inexplicably to defeat an unarmed opponent in a battle of wits, he succeeds only at the price of undoing his own argument. In his able hands, neoliberalism comes to refer to everything and nothing at all. Most notably—though hardly exclusively—it involves at once restricting and vastly expanding the role of the state in the economy; profound continuity and dramatic rupture with earlier forms of capitalism; the GOP platform and Democratic opposition to it; and so on.

To be fair, the fault is not solely Robin’s; the term is nearly vacuous in current usage. But styling himself an expert on the history of political thought, Robin assumes the burden of establishing clarity where there is obscurity. Instead, as is typical of his brash but intellectually hollow vituperations, he allows the murk to swallow him whole.

Take just one of many possible examples. Robin claims, somewhat plausibly, that the Mont Pelerin program aimed “to rollback (sic) the welfare state and social democracy, to revalorize capital and the capitalist as a moral good, to proclaim the ideological supremacy of the market over the state…” While not untrue, this description makes neoliberalism sound indistinguishable from traditional market liberalism of the sort Adam Smith himself would recognize. As if to underscore his confusion, Robin dutifully cites David Harvey, who makes exactly the same mistake on page 2 of his “brief history” of neoliberalism.

But of course Hayek et al had an altogether different program in mind, as Foucault and others have pointed out. The problem they confronted was not the welfare state (though they did oppose it) but *endemic market failure*. Since Robin knows next to nothing about economics, he has in all his work consistently misread this confrontation in purely political terms, treating policy outcomes as proxies for the fundamental impasse in economic theory. In a nutshell, mainstream economics discovered roughly a century ago that if free market principles were consistently applied, the results would inevitably include the decline of markets, competition and efficient allocation of resources. Accordingly, the liberal dogma mistakenly ascribed to Smith and his progeny would have to be jettisoned. And the target of intervention would not be state meddling but the market itself. The state would have to be empowered to maintain market discipline—against the will and interests of its participants. Hence economic neoliberalism *could not* simply be a pro-business ideology, for this would precisely repeat the liberal error (as Milton Friedman repeatedly pointed out). Several momentous consequences flow from this, none of which Robin is able to recognize or accommodate in his facile musings.

Plume 04.30.16 at 3:24 pm

Layman @41,

There is a difference about difference here. I said “there really isn’t that much difference between” the Dems and Republicans on the listed issues. You then respond by saying it’s nonsense to claim — which I didn’t — that there is no difference between Obama and Bush on those issues. Now, in relative terms, this is a mild misreading for you. You usually get things more wildly wrong than this. But it’s still wrong.

That said, Obama did keep Bush’s defense secretary; rehired his Fed chairman; continued his Wall Street bailouts and prosecuted no one responsible for the crash; kept the war in Iraq going and escalated the one in Afghanistan; opened up several new fronts in the “GWOT”; radically expanded the use of drones; created a deficit commission in the middle of a recession and staffed it with neoliberals; surrounded himself with neoliberal economic advisers like Summers, and installed another, Geithner, at Treasury; offered Boehner the Grand Bargain which included slashing Medicare and Social Security; froze government hiring and pay in the middle of a recession — which even Republican presidents never do, etc. etc.

Throw in his smash-down of Occupy; his mass deportations of undocumented workers; his relentless pushing of TPP; his stimulus package with Republican tax breaks making up 33% of it; his silencing of Single Payer and even Public Option debate; his pushing of the Heritage Foundation’s health care plan, which resulted in the very conservative ACA . . . . and, yeah, there isn’t much difference between Obama and Bush on the issues I listed . . . other than tone, rhetorical style, etc.

One of Many 04.30.16 at 3:43 pm

The Wikipedia article on ‘neoliberalism’ gives a nice rundown of the history of different but related usages of the word. And the distinction between right neoliberalism and left neoliberalism at 15 above is useful. To explain the distinction using examples that might mean something to the man on the street, the former is Thatcher and the Chicago Boys in Chile, the latter is Bill Clinton – not unrelated, but not without important differences. (The latter might better be called ‘centrist neoliberalism’, I guess.)

js. 04.30.16 at 3:58 pm

Yikes, I most certainly do not think Happy Mondays are as bad as Creed! They’re miles—continents—apart, obviously. I actually sort of like a couple of HM songs (tho mostly I don’t think they’re very good, and their not-goodness is esp. brought into relief when you consider their Manchester musical peers). Also, it’s been a while since I’ve seen it, but as I remember it, 24 Hour Party People spent a lot of its second half gently poking fun at HM. But again possible I was misreading that.

Sorry this is very OT, but I needed to clear my

namenym.bruce wilder 04.30.16 at 4:17 pm

From the late 1950s into the 1970s, the many conservative attempts to confront the Liberal Consensus included a kind of debate between Milton Friedman and the Chicago School on the one hand and John Kenneth Galbraith and the Keynesians who had shuffled thru the Kennedy-Johnson Council of Economic Advisors on the other. It was Galbraith, playing a latter day Veblen, who articulated both an interpretation of New Deal liberalism and a critique of the emerging economy of corporate business and consumerism. Milton Friedman argued “free markets” and all that.

When Charles Peters articulated the ideological surrender which was his neoliberal credo, he was rationalizing the abandonment of the liberal defense of labor unions certainly, but also the more general New Deal idea of countervailing power, which Galbraith had articulated. He was conceding that Friedman had won the debate with Galbraith and adopting Friedman’s framework, if not his libertarian credo.

Thereafter, the neoliberals were in a conversation with Friedmanite libertarians — a pretty narrow dialectic, since it excluded some paleo-conservatives as well as much of the populist labor left as well as the social democratic left. But, it seems that’s the moment when at least some strands of Mont Pelerin neoliberalism as embodied by Friedman’s storytelling merged into the decayed remains of New Deal liberalism as represented by Charles Peter’s neoliberalism and such allied developments as the Third Way politics of the New Democrats and Bill Clinton.

That dialectic with the Friedmanite libertarian conservatives was a feature, not a bug of the Charles Peters neoliberalism. Their joint effort produced a powerful rhetorical machine capable of generating an endless stream of pundit dichotomies and they could legitimize each other. Their joint efforts at consensus and mutual legitimacy gave weight to the “Washington Consensus” later adopted by the bureaucracy of the World Bank and IMF and exported globally as another source for a similar set of doctrines labelled, yet again, as “neoliberal”.

The similarity of tone and substance in these various strands, each adopting the same label, that has given “neoliberal” such great currency. They have been like tributaries coming together into an unstoppable river.

Chris 04.30.16 at 4:51 pm

I have mostly seen the term Neoliberalism used by Europeans. In the US, it is nothing like Liberalism. It is like Libertarianism.

LFC 04.30.16 at 5:09 pm

Chris @45

I have mostly seen the term Neoliberalism used by Europeans. In the US, it is nothing like Liberalism. It is like Libertarianism.

No it isn’t. There is no similarity to speak of betw libertarianism and Charles Peters/Dem Leadership Council neoliberalism.

LFC 04.30.16 at 5:12 pm

p.s. even after reading BW @44, I still don’t think there’s much similarity.

Mdc 04.30.16 at 5:34 pm

Agreed w kidneystones (!) @38.

Jason Weidner 04.30.16 at 6:03 pm

The following takes nothing away from your main points about the origins and development of neoliberalism, but may be of some interest.

The OED gives the following examples of the use of the term neoliberal:

1898Â Â Econ. Jrnl. 8 494Â Â “We must..bear in mind what is that hedonistic world, that realm of pure political economy, ever kept in view by the adepts of Neo-liberalism.

1924Â Â H. E. Barnes Sociol. & Polit. Theory ix. ii. 161Â Â He [sc. Leonard T. Hobhouse] represents the sociological expression of the Neo-Liberalism of England that has produced..more constructive social legislation than the combined product of earlier English governments.”

1938  Polit. Sci. Q. 53 133,  ” I deplore in an attempt to state a theory and formulate a practice of neo-liberalism, a trace of illiberalism and intolerence toward those who differ from the new credo.”

1978  Washington Post 10 Sept. c1/2  “Political necessities are headed … toward much more serious government intervention in the private economy. If you’re looking for a shorthand phrase, it might be more accurate to predict a period of ‘neo-liberalism’.”

1992Â Â Globe & Mail (Toronto) 1 May d1/5Â Â “These ideas include, beside free trade: privatization, deregulation, competitiveness, social-spending cutbacks and deficit reduction. The ensemble may be called neoconservatism, neoliberalism, the free market, [etc.].”

The first example an article by French economist and historian of economic thought Charles Gide in The Economic Journal (1898). The article deals with the idea and practice of co-operation. Gide begins the article by introducing a critique of co-operation made by the Italian economist Maffeo Pantaleoni.

According to Gide, Pantaleoni argues “that co-operation has not enriched economic science with any fresh principle whatever, and that, in practice, it can add nothing to what we get by way of natural result from the free play of competition†(Gide, 1898, p. 490). Gide refers to Pantaleoni as “one of the highest authorties†of “the Neo-liberal school†(492). Gide defends the idea and practice of co-operation, providing a rebuttal to Pantaleoni. In his rebuttal, Gide insists that “we must from the first bear in mind what is that hedonistic world, that realm of pure political economy, ever kept in view by the adepts of Neo-liberalism when they attack us and cry triumphantly, “You will never get further nor do better!†The answer, Gide argues, is that the “hedonistic world†of the Neo-liberals is:

“one in which free competition will reign absolutely; where all monopoly by right or of fact will be abolished; where every individual will be conversant with his true interests, and as well equipped as any one else to fight for them; where everything will be carried on by genuinely free contract, in which each contracting party will weigh in a subjective balance, infallibly exact, the final utility of the object to be disposed of and of the object to be acquired,-a bargaining where neither violence, nor fraud, nor lies, nor ignorance, nor dependence on others, nor any foreign disturbing element whatever—for instance the miserable preoccupation as to whether there’s anything for supper—will come in to upset so delicate an operation: a world where the law of supply and demand will bring about the maximum of utility for both individual and society, and will always send back the barometric needle, at once and without friction, to ‘set fair’—I mean to the fair price (494-5).”

Of course, Gide points out, this world does not exist; or rather, it exists “nowhere save in the inaccessible regions of abstract thought. It has no more relation to the society in which we actually live, than has the world of pure geometry with the configuration of the earth or the human form†(495). Furthermore, Gide argues, given that this imagined world of Neo-liberalism is a utopia, Neo-liberals such as Pantaleoni ought to consider the possibility that co-operation is instead the best way of producing “that which laisser faire and individualism never will,—a society governed by free competition and free contract†(495).

For Gide, the central problem that the new Liberals fail to account for is that the fin de siècle economy is characterized not by pure competition but by an “anti-social and demoralising competition…[a] struggle for existence in which the least scrupulous win and the most honest go to the wall†(496). Moreover, Gide argues, the purpose of the various “co-operative societies†is precisely to “abolish everything which tends to vitiate free consent between co-exchangers,†including: “adulteration of food, false weights, lying advertisements, tips to servants, usury, sale by credit which is but a form of usury, and, above all, the friction resulting from an excessive number of intermediaries and in fluctuations of price or an inert balance†(496).

In an interesting argumentative maneuver, Gide points out that under Liberal theorizations of perfect competition there is not profit, since “the value of things is always brought down to the level of the cost of productionâ€â€”and this is precisely the goal of co-operative societies: “to abolish profit!†(498).

Lurking in the background, and at times even appearing in the foreground, of Gide’s discussion of cooperatives is “the Social Question.†This term, with its origins in 19th century Europe and North America, referred to the consequences of industrial capitalism—or, as Tony Judt put it: “How could the virtues of economic progress be secured in light of the political and moral threat posed by the condition of the working class? Or, more cynically, how was social upheaval to be headed off in a society wedded to the benefits that came from the profitable exploitation of a large class of low-paid and existentially discontented persons?â€

Lupita 04.30.16 at 6:31 pm

@ZM

governance in Australia has shown similar turns as that in the USA

Earlier in your post, you mentioned the similarities in timing and ideology between Thatcher and Reagan, resulting in three Anglophone countries going neoliberal at the same time: the UK, the US, and Australia, which points to the existence of global forces at play. If we add IMF-imposed neoliberalism in Latin America and elsewhere, by the year 2000 the world ended up, either through democratic elections or imposition, with a global system characterized by independent central banks, a deregulated financial system, weak labor unions, and decreased social spending. The banks had taken over.

The underlying global conditions that explain this world-wide phenomenon are, starting in the 80s, the US-USSR stand-off in which the West needed to prove the superiority of its system and, continuing into the 90s after the fall of the USSR, the consolidation of a unipolar system with the US at its helm. It was all about Western supremacy.

I think the notion of supremacy in Western countries (not racial supremacy anymore, but modern, objective, technocratic, mathematical model, freedom loving supremacy), is part of a deeply ingrained identity in which being the only ones responsible enough to control nuclear weapons, patrol the oceans, and head global institutions is considered as part of the natural order. However, now that their own personal welfare and material comfort is at stake, many are timidly beginning to see the big picture of empire and question their personal alliance to it.

At this point, I believe it would be wise to look at the Latin American experience. Recent history shows that when people voted out neoliberalism, it was then imposed, not by bombs, but by the threat of an equally devastating financial crisis. TINA means the threat of economic ruin is so certain that heads of government, even socialists like Lula and Tsipras, prefer to give in than to preside over the certain ruin of their country.

Lupita 04.30.16 at 6:50 pm

@michael braverman

the term is nearly vacuous in current usage.

In case you haven’t noticed, commenters on this thread come from different countires and have different languages as their mother tongue. If we can talk about neoliberalism here and understand each other, that means that “neoliberalism†is precise enough to be understood across language groups and cultures and your assertion that it is a vacuous term is pretty much debunked.

I would respectfully urge you to burst out of your US-centric bubble and acknowledge the great work of economists from all over the world who have described and explained neoliberalism, of the political parties and heads of state who have stood up to its imposition, and of the courage and determination of popular movements such as the people of Cochabamba and the Zapatistas..

William Berry 04.30.16 at 6:52 pm

@kidneystones, Mdc:

Soullite, like Brett Bellmore and Data Tatushkia (Ze K), has been banned here before (and doubtless at many another “responsible” site). But time passes and, like the undead, they just keep coming back.

LFC 04.30.16 at 7:09 pm

Jason Weidner @52

Interesting. I recall *many* years ago seeing a history of economic thought by Gide and Rist.

I think, however, that usage of a term as malleable as ‘neoliberalism’ has to be seen very much in the context of a particular time and place; thus, whether any kind of line can be convincingly drawn from Maffeo Pantaleoni to Charles Peters — or, as Corey would have it, from Mont Pelerin to C. Peters — must be, at a minimum, highly debatable. The line from Maffeo Pantaleoni to Thatcher and Reagan seems much more direct.

Donald 04.30.16 at 7:10 pm

Braverman– it’d be more useful if you’d flesh out what you mean in your final sentence. It sounds interesting, but I have no idea what you mean. Not surprising, since I am no expert on the history of economics or politics.

More generally, the comment section here has gotten increasingly hostile. ( I’ve contributed in a small way.) The circular firing squad here has become a fractal, with everyone shooting at everyone else.

LFC 04.30.16 at 7:36 pm

michael braverman @42

The state would have to be empowered to maintain market discipline—against the will and interests of its participants.

How? You leave off the comment just where it starts to get interesting.

Btw, your tone toward C. Robin is unnecessarily insulting. I certainly don’t always agree w him — I disagree with certain things in ‘The Reactionary Mind’ (I haven’t read his ‘Fear’ except for the excerpts he put up here some time ago). However, your “brash but intellectually hollow vituperations” goes overboard, imo.

phenomenal cat 04.30.16 at 8:17 pm

“michael braverman @42

The state would have to be empowered to maintain market discipline—against the will and interests of its participants.

How? You leave off the comment just where it starts to get interesting.” –LFC @58

Yeah, condescending commenter is on to something with that line, but it is still too vague and could give the wrong impression, especially the phrase “maintain market discipline.”

It’s not so much discipline of the market which neoliberals saw as necessary for various apparatuses of the state to maintain. Rather neoliberals understood that state interventions, support, and coordination were necessary for redefining swathes of social and political life in economic terms. In other words, the power of state was necessary to make the “non-economic” amenable to various and particular kinds of market capture.

It’s never been about “market discipline.” It’s always been about disciplining everything else for the market.

Colin Danby 04.30.16 at 8:22 pm

Re @42: yes, the Braverman comment is dreadful, and its reading of Foucault eccentric too.

The place to start is Foucault’s 1979 biopolitics lectures, published in French in ’04 and English in ’08. An earlier version, with two of the lectures, emerged in 1991 in the Burchell/Gordon/Miller _Foucault Effect_ (Chicago).

And really (re@42), *everyone knows* the term has been overgeneralized. it is not a logical conclusion from that obvious fact that there is no such thing as neoliberalism.

bruce wilder 04.30.16 at 8:23 pm

I did not say there was a similarity, at least I did not intend to. More like, there is a symbiosis, as they simulate debates or disputes between them and further common goals by compromise with the other. That last is a particularly neat trick for practical politics, as neoliberals can avow one goal in principal while pursuing another in compromise.

bob mcmanus 04.30.16 at 8:40 pm

59: It’s always been about disciplining everything else for the market.

The place to start is Foucault’s 1979 biopolitics lectures

Nah, it’s ok to start a few Foucault decades earlier, since, although he might have denied it, much of his work delineated the everyday mechanisms of Gramscian hegemony.

LFC 04.30.16 at 10:09 pm

Plume @43

Re Obama “kept the war in Iraq going”:

Actually Obama ended the U.S. combat role in Iraq, and the Repubs criticized him for not arranging a status-of-forces agreement for a continued troop presence, even though Maliki made quite clear he didn’t want one. (According to McCain and Graham, it was the admin’s ‘fault’ for not negotiating long enough w Maliki. Or something.)

alfredlordbleep 04.30.16 at 10:24 pm

Plume @2:44 pm

There really isn’t that much difference between them (Dems and Republicans) on economic, war, empire, surveillance issues. Even taxes, which was once a sure-fire point of departure. And because it’s all relative now and PoMod, “liberals†can claim massive differences where they don’t exist, because the bar has been lowered so much. Like the paltry increase at the top from 35% to 39.6%, with even that weakened by making all Bush tax cuts permanent from dollar one to 400K. Weakened further by raising the top from 250K to 400K.

It should be noted that taxation of income from wealth went down, down to 15% under Bush-Cheney and is back up to 23.8% (in the limiting case) under Obama as a combo of increase on cap gains÷nds and the ObamaCare surtax (I leave out the fine print. . . )

Plume 04.30.16 at 10:30 pm

LFC @64,

It took him nearly three years to do so, and it’s still not really over. The last “official” combat troops left in December of 2011, but we still have a presence there of several thousand.

From Wiki:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iraq_War

LFC 04.30.16 at 11:19 pm

still not really over

that is, unfortunately, true, in more than respect.

LFC 04.30.16 at 11:20 pm

more than one respect.

ok, time to get offline.

tony lynch 04.30.16 at 11:56 pm

layman@41 perfect example der Narzissmus der klienen Differenzen. Lovely.

ifthethunderdontgetya™³²®© 05.01.16 at 12:54 am

When people whine about the term neoliberal, I an willing to compromise.

How about, “corporatist and warmonger?”

~

J-D 05.01.16 at 2:12 am

kidneystones @11

‘For some reason, however, the poor are listening to David Brooks and Jon Chait.’

I wouldn’t be prepared to guess who the poor are listening to. What’s your source of information on this point? And, if they are listening to David Brooks and Jon Chait, what are David Brooks and Jon Chait suggesting that they do? Are they suggesting that the poor should vote for Donald Trump?

‘Many of the geriatric self-satisfied here are blissfully unaware of just how bad things are for young people.’

So tell us, how bad are things for young people in the US? I’ve read about some of them being shot dead by the police — is that the sort of thing you had in mind?

‘The result is the Salon piece linked, and others, that question whether Trump may well be the better candidate.’

Does Salon speak for, or to, the poor? The linked piece doesn’t argue that Trump will be a better President for the poor in the sense of achieving more for the poor; one of the reasons given for thinking that Trump might be the better candidate is an expectation that he would achieve nothing as a President.

‘It’s a free country (at present). But if any think voters watching protesters force Trump to crawl under fences, smash police cars, and silence free speech on campus are winning over the majority of voters, many of whom have not had a pay raise in 18 years, I’d suggest that assumption needs a re-think.’

To me it seems unlikely in the extreme that people who have not had a pay raise in eighteen years are thinking to themselves ‘It’s because they’re silencing free speech on campuses, that’s why I haven’t had a pay raise’ or ‘It’s because people smash police cars, that’s why I haven’t had a pay raise’. You appear to be suggesting a connection between things which are not connected. (Also, I don’t know what makes you think it’s a free country.)

‘There’s a revolution taking place in America today – and it’s a rejection in many respects of many of the most closely held assumptions of new liberalism. Whether Trump can succeed in overturning the old order is a different question.’

To say that there is a revolution but then to suggest that it’s not certain the old order will be overturned does not make sense: if the old order is not overturned, then there’s no revolution.

Val 05.01.16 at 2:17 am

Mdc @ 50

I also find myself in agreement with Kidneystones (!) and have drawn the comment @ 36 to Corey Robin’s attention, hope he sees it.

J-D 05.01.16 at 2:27 am

bob mcmanus @34

‘And it really isn’t that Democratic Elites are cynically using Wall Street as a money spigot; the fact is that Wall Street is no longer your grandaddy’s Wall Street, much more socially liberal, and Democrats like the Clintons and Obamas genuinely prefer the company of the Bill Gates and Mark Cubans and Summers and don’t want to have anything to do with the working class or poor.’

What’s the contrast here? How much of the socialising of Democrats like Franklin Roosevelt, or Democrats like John Kennedy, was with the working class or the poor?

Plume 05.01.16 at 2:49 am

J-D @72,

Those earlier Dems came from the upper class, and seemed to have a certain noblesse oblige. They actually talked about the poor, a lot (especially RFK), and created programs they thought would help them. In general, they didn’t try to bootstrapsplain things, as is now the wont of the neo-Dems too. Those neo-Dems typically come from the middle class, and once they escape, seem to want to pull the ladder up after them and make the poor feel guilty about their plight in the bargain. They endlessly go on and on about how hard work and dedication and education will lift everyone, blah blah blah. They seem not to recognize the rarity of what they, themselves, have done, or the massive amounts of help they had along the way, or the much lower costs in their day — and sheer luck. And now, we get John Lewis, on behalf of Hillary, mimicking the “free stuff” rhetoric of the Republicans to further guilt the non-rich. To further guilt people who think tuition-free public schools is a great idea. It is.

In short, they aren’t that different from propertarians who also think that if a few can seemingly become billionaires overnight, anyone can, and anyone who doesn’t is just a lazy SOB. For propertarians, the vehicle is business ownership. For neo-Dems, it’s education. Both have amnesia, on a personal and systemic level. And both want to pull up the ladder after they’re own ascension.

Peter T 05.01.16 at 3:02 am

Since the earlier thread on this has been taken over by Brett, Brett and Plume, I’ll continue my historically-inspired musings here. I was thinking about the social bases of liberalism as contrasted with neo-liberalism. Liberalism found its original home in the British upper middle classes, a group concerned to preserve their access to the state, but fearful of the magnates who controlled the state after 1688. As the middle class broadened after 1850 or so, it expanded its political reach – although it was then pushing as much against the ‘socialist” working classes as the oligarchy. A comparison with the continent is instructive – the same classes there supported royal absolutism, since the middle classes were smaller and more dependent on the state, and the magnate threat larger and more direct (the magnates wanted to neuter the state, not control it).

Neo-liberalism has, as others have pointed out, not much a political base at all. It’s hostile to the security and settled relations that are the hallmarks of middle class life as much as it is to the communal solidarity of the working classes. It’s an ideology of administrators working with and for the new magnates – the global rich and their placemen. The careers of people like Blair, the Clintons, or their Australian counterparts illustrate this nicely.

The relationship to state power is also quite different. Former magnate groups – the Czartoryskis, Sapiehas, Radziwills and Eszterhazys who disabled the Polish and Hungarian states could rest confident that their private armies could keep the serfs in line, and the networks of commercial middlemen who translated their produce into urban palaces and Haydn symphonies would survive changes of regime (in this they were right – as a group most did fine up to the 1930s). British magnate power is more complex – they needed professional and political allies if they were to keep the French out and the Irish down and, in a strongly centralised state, they could not fall back on local power.