Thanks to James Wimberley for prompting me to write this, and alerting me to the data on China’s emissions

Most of the news these days is bad, and that’s true of the climate. Even as climatic disasters worsen, the Trump regime is doing its best to dismantle US and global efforts to decarbonize our energy systems. But there is still some surprisingly good news.

First, China’s emissions from coal-fired electricity appear to have peaked. Thermal power generation fell 5.8 per cent in January and February this year, relative to 2024. The only times this has happened previously were during the Covid lockdowns and in the aftermath of the GFC. On this occasion, total power demand fell by 1.5 per cent due to a warm winter, but the big decline in coal was due to increased solar generation.

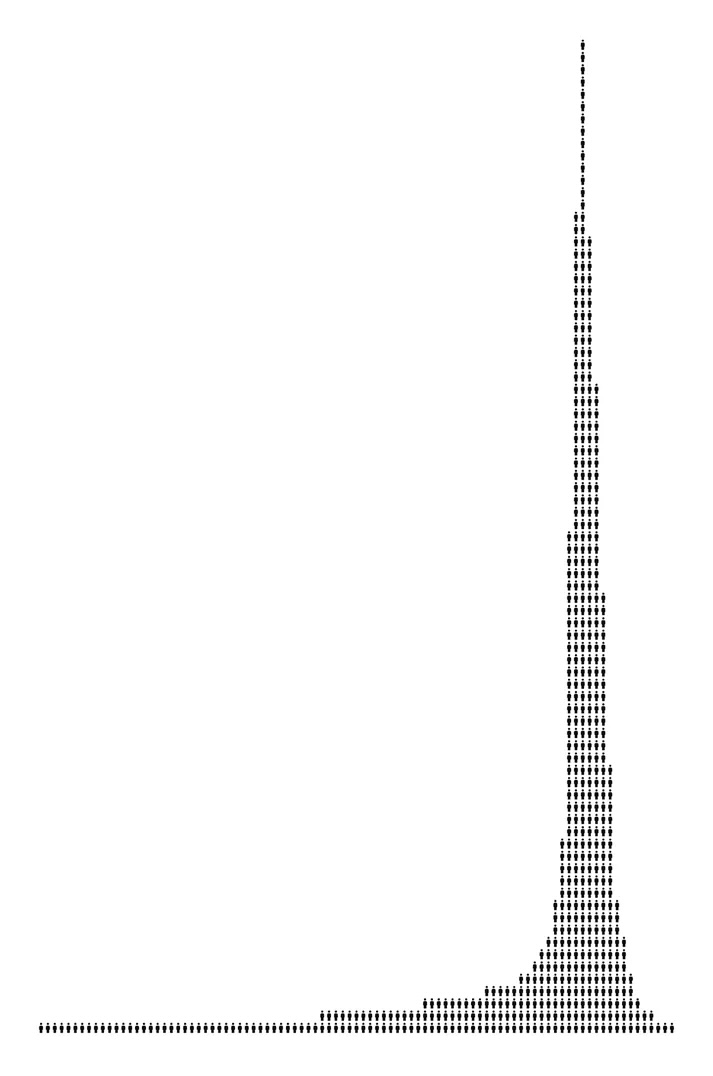

And China’s solar industry keeps on growing on all fronts. China added another 277 GW of PV last year, more than all the capacity installed in the world up to 2015. Recorded exports were 236GW, another record. Since production was estimated at more than 600 GW, it seems likely there are some unrecorded installations.

All this is happening even though new coal-fired power stations are still being built, largely for political rather than economic reasons. It seems likely that these plants will see limited operation as solar power (augmented with storage) meets more and more demand.

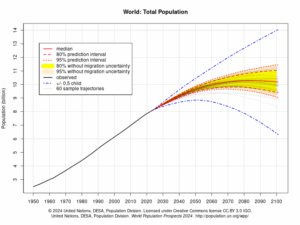

Second, the great AI boom in electricity demand has turned out to be a mirage, at least so far. This isn’t always obvious from the breathless tone of coverage. For example, this story leads with the claim that “Electricity consumption by data centers will more than double by 2030”, but leaves the reader to calculate that this implies an increase of just 1.5% in global demand.

Notably, Microsoft which was one of the leading promoters of claims about electricity demand is now scaling back its investments. And large numbers of data centres in China are apparently idle

Even Trump is helping in perverse ways. His policies are already reducing projections of US economic growth, which will accelerate the decline of coal-fired power in particular. His attempts to defy economic reality by keeping coal plants open are unlikely to have much effect in this context.

And coal is on the way out in many other countries. Finland just closed its last coal-fired powerand even laggards like Poland are making progress

The picture is less promising with the transition to electric vehicles, which has slowed in most places. But once we complete the transition to solar, wind and storage, electricity will be massively cheaper. And once again, China is a bright sport, with electrics taking 25 per cent of the market in 2024, and new vehicles becoming cheaper and cheaper. BYD is now offering an electric car in Australia for less than $A30 000 (a bit under $20 000 US).

As I argued a year ago, the irresistible force of ultra-cheap solar PV will overcome the seemingly immovable barriers in its way.

Note Links got lost in copying from my Substack. You can find them here