by Chris Bertram on November 11, 2021

Lately, I find I’ve been spending more and more time looking at Facebook groups of old photographs of Bristol, the city where I live. I particularly enjoy the aerial photographs of the interwar period, often colorized. There are lots of reasons for this: I like photographs, I like history, I like cities. But it isn’t just Bristol, I can also spend hours on the Shorpy site, sometimes going to Google Street View for a modern take, and I own several books comparing the Parises of Marville and Atget and the New York of Berenice Abbott to the same scenes today, as well as multiple volumes of Reece Winstone’s collection of historic Bristol pictures. So what’s the attraction, indeed the compulsion? What is drawing me and others to these scenes? And does this attraction also have a problematic side to it?

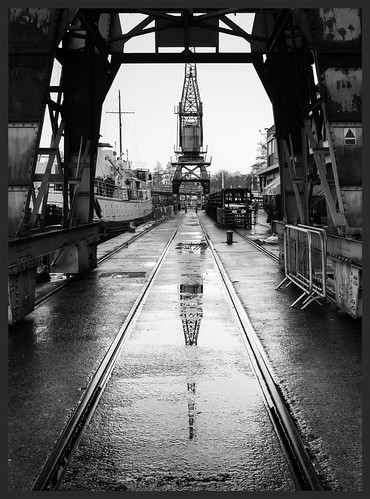

One common response to the images is a sense of thwarted possibility. You see a functioning, bustling city, full of life, and full of beatiful surviving buildings, densely packed. The train is everywhere, with bridges, tracks, sidings, sheds to match. Sometimes a locomotive is in view. The rail infrastructure criss-crosses with the water, canal and harbours. Factories with their chimneys sit adjacent to medieval churches with their towers and spires. The technology often looks amazing, as with the Ashton Avenue Bridge (1905)(covered for photoblogging a while back), which in its day was a double-decker swing structure, with road on the top deck and rail running below. These days it has but one functioning level – the old rail deck is for pedestrians and cyclists – and it hasn’t swung since 1951. The “then” pictures give us the romance of industrial modernity combined with the charm of the medieval.

[click to continue…]

by Ingrid Robeyns on July 28, 2018

I hope those of you based in the right places enjoyed the red moon last night. The day before yesterday, we enjoyed a fabulous bright and almost full moon, while sipping some French wine on top of a hill in the Midi-Pyrénées. But alas, yesterday we had only clouds around the time we had hoped to enjoy the red moon. Still, they were pretty spectacular too – at least, a bit earlier in the evening.

by Chris Bertram on November 13, 2017

We spent a few fun hours at the Paris Photo exhibition at the Grand Palais on Saturday. The first time I’d been. Lots to see and lots to like, but also quite a lot to dislike. My attention was caught by a copy of Kertesz’s Chez Mondrian, which is one of my favourite photos of all time (#2 after Cartier-Bresson’s Madrid) on the stall of Bruce Silverstein, the New York dealers. I sauntered up to the assistant and asked how much it was going for, knowing already that it would be beyond my budget: “1.2 million” she said. I’m not clear whether that was dollars or euros, but it doesn’t matter much. It was a print made for an exhibition in 1927, and as such, unique, though it looks like most other renderings of Chez Mondrian.

There is something, to my mind rather off about the enormous sums being paid for photographs. After all, with the exception of daguerreotypes and similar they are actually produced for reproduction and largely only exist in the form of copies of themselves (the negative being rarely for sale). Some of what was on sale for large amounts were shots of really poor and suffering people taken by photographers acting from moral or political motives: all grist to the mill of the gallerists.

Having looked around several stalls containing vintage photography, I asked one assistant why I had not seen a single autochrome. Apparently they have very little commercial value because of doubts about the long-term stability of the originals. I still think it anomalous there aren’t any, I said, pointing out that we were in Paris, where the Albert Kahn Museum (perpetually fermé pour travaux) has perhaps the world’s largest collection. Alas, she had never heard of Albert Kahn.

(For myself, I bought and was bought, some books by Harry Gruyaert, a Belgian colourist at Magnum whom I really rate very highly.)

by Chris Bertram on September 17, 2017

Back to Sunday Photoblogging. I’ve been on hiatus from CT due to some family matters, and others have taken up the photoblogging job. This is the Étang de Montady as seen from the Oppidum d’Ensérune (both near Béziers in Languedoc). Both have Wikipedia entries, so please consult, but the story is that monks constructed this in the 13th century. They drained the swamp/pond by creating a drain at a central point which flows through an underground culvert and the radial ditches that result force the fields into their triangular pattern.

by Henry Farrell on July 22, 2017

(I took this photo with my phone in Dulles Airport a couple of weeks ago)

by John Holbo on May 19, 2017

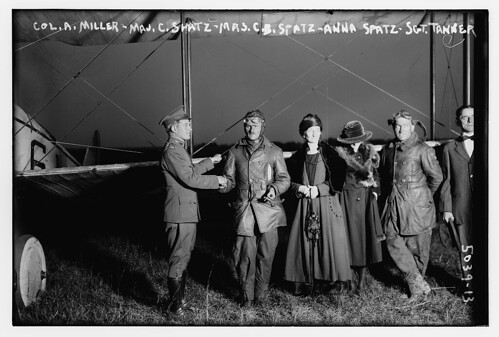

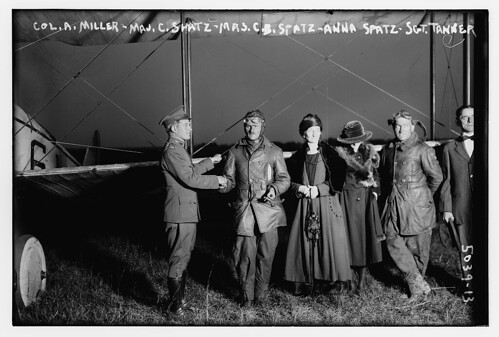

Wonder what this one is. Please offer your best attempt at Maj. and Mrs. Spatz fanfic in comments. (I love the Flickr Library of Congress photo feed.)

by Chris Bertram on March 19, 2017

by Chris Bertram on March 12, 2017

by Chris Bertram on March 5, 2017

by Chris Bertram on February 26, 2017

by Chris Bertram on February 19, 2017

by Chris Bertram on February 12, 2017

by Chris Bertram on February 5, 2017

by John Holbo on October 23, 2016

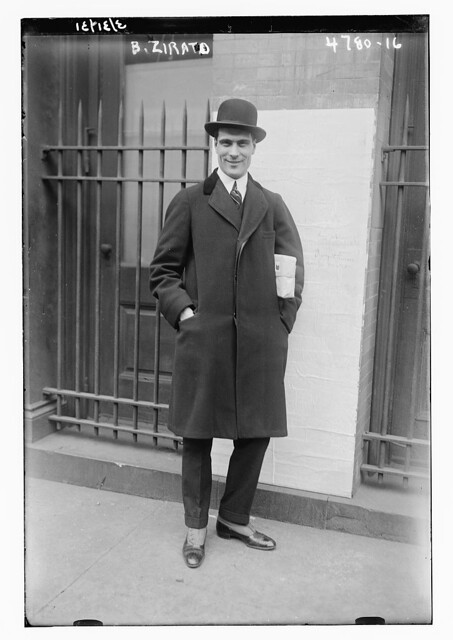

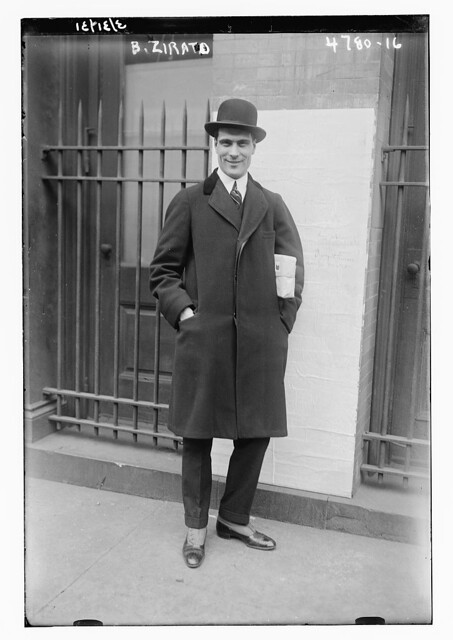

In case my Kant-to-Hegel post is a bit heavy, for a Sunday, here’s a snappy, snazzy guy I spotted in the Library of Congress Flickr feed.

Note how this guy seems to be leading with his … thighs? Can he walk like that? Looks like a Zim cartoon/caricature. It’s a good look.

Chris Bertram is, of course, free to post his own Sunday photo later. I don’t mean to horn in on his territory!

by Chris Bertram on August 10, 2016

There’s nothing like a few unexpected days at home to allow you to discover new things, and the great find of the past few days — thanks to a tweet from Fernando Sdrigotti @f_sd — has been to watch (via Youtube, start [here](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vpijOSSlZCI) five programmes in all) some BBC documentaries about Albert Kahn and his Archives of the Planet, now preserved at the [Musée Albert Kahn](http://albert-kahn.hauts-de-seine.fr/) outside Paris. Born in Alsace, Kahn was displaced by the Prussian seizure of the territory in 1871 and became immensely rich though banking and investing in diamonds. But he was also an idealist, convinced that if the various tribes of humanity only knew one another better they would empathize more and would be less likely to go to war. In pursuit of this hope, and taking advantage of the Lumière Brothers’ [Autochrome](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autochrome_Lumi%C3%A8re) colour process, he sent teams of photographers to all parts of the globe and, before the First World War, caught many forms of life on the edge of being swept away by globalisation, war and revolution. (There’s quite a good selection [here](http://www.afar.com/magazine/a-trip-through-time) but google away.) Pictures taken around the Balkans, for example, depict the immense variety of different cultures living side-by-side at the time and then later we see the sad stream of refugees from the second Balkan War as they head from Salonika towards Turkey. Kahn’s operative document rural life in Galway, harsh penal regimes in Mongolia, elite life in Japan and a tranquil Rio de Janeiro with little traffic and few people.

Kahn’s hope for a peaceful world was lost in 1914, but we owe to his project many images of wartime France, particularly the life of ordinary people behind the lines. Postwar, Kahn was a great supporter of the League of Nations and, again, his operatives were on hand to document many of the upheavals of the inter-war years, such as the burning of Smyrna in 1922 (as Izmir, the city is once again crowded with refugees today) and the abortive attempt to found the Rhenish Republic in 1923. Many of the photographs are included in a book by David Okuefuna, *The Wonderful World of Albert Kahn: Colour Photographs from a Lost Age* (BBC Books, 2008). Sadly, Kahn was ruined by the Great Depression and died in Paris shorly after the Germans invaded in 1940. He seems little-known today, but there’s a lot of material out there that’s worth your time.