The stupidest decision I made as an undergraduate was not to go to Jerry Cohen’s lectures on Marxism. The London colleges, despite being almost completely separate, pooled resources to give Philosophy lecture courses for 2nd and 3rd years. The lectures were held in tiny lecture rooms at Birkbeck – I seem to remember usually being there on Tuesday and Thursday mornings. The relevant term, Jerry’s lectures were on the same morning as the philosophy of language and philosophy of mind courses; I knew that I only had the concentration for 2, and, despite being, I presumed, some sort of Marxist (unaffiliated), I had no interest in political philosophy (not least because I believed some quite unsubtle version of Marx’s theory of history). (I’ll also admit that I responded somewhat to peer-pressure; my mate Adrian was not going to the Marxism lectures, and it was fun to have coffee with him instead). Like, as I later found out, Jerry, I had not come to study philosophy in order to learn about political ideas – I’d been politically active since I was 15 and had been exposed to all the political ideas that implied while I was in secondary school (taught History by a member of the CPB (M-L); indirectly recruited to the peace movement by a former CPGBer; worked with someone in the NCP, various SWPers; engaged in conspiratorial faction fights within the peace movement against various Trotskyists including CB’s flatmate of that time… you get the idea). I went to university to study something that I knew I couldn’t learn any other way – analytical philosophy. So it was easy to pass up Jerry’s lectures, even though everyone said they were brilliant, and even though I was interested in Marxism.

Later Jerry influenced me enormously. I bought Karl Marx’s Theory of History A Defence

as a celebration of getting my degree and read it first on a trip after graduating; I studied it about half-way through graduate school (along with these papers by Levine and Wright, and Levine and Sober), and more than anything else was responsible for my shift away from philosophy of language to political philosophy; because, like most readers of KMTH, I became convinced that the version of Marx’s theory of history that had seemed to me to make political philosophy irrelevant was false. I then read what is still my favourite Jerry paper, “The Structure of Proletarian Unfreedom”, and subsequently saw him lecture at UCLA; from then on I guess I read nearly everything he published, as soon as I could get my hands on it.

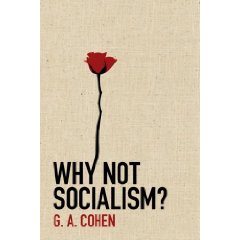

So now, what I presume is his final book, Why Not Socialism? (UK

) (I hope there’ll be other publications – presumably someone, probably one of our readers, is taking responsibility for seeing some of the work that Jerry left unpublished into print) is in my hands. Princeton have deliberately created it to be like On Bullshit

– very short, beautifully made, small enough to fit in a smallish pocket. People have been calling it the “camping trip” book; he uses the conceit of a camping trip to demonstrate that organizing social life around the two principles that, for him, define socialism – a very stringent version of equality of opportunity, and a very demanding principle of community – is very appealing to most people in some circumstances. He goes on to demonstrate that the appeal of these principles is not superficial, or restricted to unusual circumstances such as a camping trip, but are appealing at a society-wide level too:

It does seem to me that all people of goodwill would welcome the news that it had become possible to proceed otherwise [i.e. in ways that tapped into our nobler, rather than our more selfish, motives] perhaps, for example, because some economists had invented clever ways of harnessing and organizing our capacity for generosity toward others.

The problem, for Cohen, is that we lack such technology. We should not pretend that we have such a technology, but nor should we pretend that the search for it is futile, or that the lack of it means that the organizing principles of our own society are more appealing than they, in fact, are. (For a fuller description and a critique, of which I’d appreciate some discussion, see Herb Gintis’s review,, already on the amazon page!)

It’s wonderful – if you knew Jerry you can hear him speaking every word. If you didn’t know him, you get a sense of just how serious he was, but also just how funny (after describing the camping trip, he reveals, in an unusually understated way, that he, himself, wouldn’t dream of going camping – “I’m not outdoorsy, or, at any rate, I’m not outdoorsy overnight-without-a-mattress-wise” – but specifies that his question is “ isn’t this, the socialist way, with collective property and planned mutual giving, rather obviously the best way to run a camping trip, whether or not you actually like camping?”. [1] I’ve bought 10 copies to give to various recalcitrant friends and in-laws.

But the book reminds me why I’ve never regretted my stupid decision to miss his lectures. They would have been brilliant, and would almost certainly have redirected me away from my interests prematurely. There’s a small professional reason for being glad that didn’t happen; I appreciate the investment I made in learning how to do core philosophy. But mainly it is personal. Redirected then, I’d have made different choices about, for example, whether or where to go to graduate school. The things that are of real value in my life all turn on that decision – had I not gone to LA when I did, and developed the way I did, I’d not have met my wife and had my kids. Beside them everything else pales, and I still feel a shiver of horror at the thought that I might not have made the choices I did. I know Jerry would understand my lack of regret.

[1] I’m in Jerry’s camp on this, unlike our great mutual friend Erik.

{ 87 comments }

Eamonn Callan 09.01.09 at 3:24 pm

That’s a lovely post, Harry. Buying a copy of Karl Marx’s Theory of History as one’s graduation present brought a smile to my lips. I think I bought LP recordings of Beethoven’s last quartets. Much as I admire Jerry Cohen, I think I got the better deal

tristero 09.01.09 at 3:53 pm

I have no doubt we lack the technology to make socialism work. We also have some fairly good precedents that, possibly because of the lack of such a technology, socialist regimes rapidly degenerate into totalitarianism, poverty, and terror. I see nothing on the horizon that gives me the slightest confidence that a socialist-enabling technology could be invented and – equally important – would be adopted and – equally important – would be desirable.

As persuasive as Jerry Cohen may be in his book, I have to agree with the previous commenter: There is far more to gain about the human condition and our potential as humans from listening to late Beethoven.

Chris Bertram 09.01.09 at 4:05 pm

Unfortunately, the book isn’t released in the UK yet (Jerry himself never saw a final copy). I’m hoping get one in the next few days and to post something here. Since I haven’t read the book, it would be premature to respond to Gintis, but Jerry’s acceptance of a personal prerogative in other writings would seem to be in tension with Gintis’s account. Gintis’s final, sub-Nietzschean, para seems to conflate the desire to achieve excellence (and perhaps to be honoured for that) with the securing of material advantage over others as a consequence.

Sebastian 09.01.09 at 4:06 pm

Obviously haven’t read the book yet, so I don’t know if Herb Gintis’ points are fair in relation to the book, but they appear strong. The problem with a camping analogy is that we often go camping with family or self-selected friends that we treat as kin or close to kin. Gintis seems to claim the Cohen’s book doesn’t really deal with the fact that the generosity Cohen describes is usually within close bonds, and attenuates quickly as the bonds become less immediate. This would tend to strike me as a very serious critique.

Ramiro 09.01.09 at 4:13 pm

I was lucky enough to be in his Fall 08 course in Columbia. We were an odd mix of lawyers-to-be and philosophy students, analyzing every chapter of Rescuing Justice and Inequality. I will never forget Jerry’s patience, analytical wit and careful consideration to all of our ideas and opinions. Of course, I will never forget the jokes, or impressions. The Crooked Timber and its commentary on Jerry has been a wonderful medicine for us who will miss not having the opportunity to meet him again. I can’t wait to get my hands on Why Not Socialism. Can’t wait.

Salient 09.01.09 at 4:22 pm

What fun — I read the book last night and posted a comment on its prescience/applicability in the Rationing thread not too long ago, only to be caught in moderation for use of the word social’sm. Then I tried to post the following humorous remark here, to be caught by moderation again. Sigh.

So, to answer Cohen’s question so as to delight a handful of CT commenters:

Q. Why not social’sm?

A. Because it contains the word ‘cial’s.’

…will be back with some critique of Herb Gintis’s review some time later. A short preparatory comment:

For instance, family is virtually universally, in every successful society, more salient than community.

Hrm. That’s not true in the very strict sense that Gintis needs it to be true, in order for the statement to obtain as criticism. I think Plato dealt with this rather effectively in the Republic: the definition of who is conceptualized as “kin” is quite mutable. And, Cohen mentions this specifically, when he mentions “the lyrics of a left-wing song from his childhood” (paraphrased because I don’t have the book at hand).

Matt 09.01.09 at 4:30 pm

Gintis is an extraordinary reviewer on Amazon. Whatever you think of his particular reviews (I’ve found some better than others) the fact that he has several hundred (I believe), and that they are nearly all fairly substantive, is pretty amazing. I suspect I’ll share many of his worries when I read the book, as they sound quite a bit like the worries I’ve had when reading much of Cohen’s other work.

Harry- have you read Alec Nove’s _The Economics of Feasible Socialism_? If so, I’m curious what you think of it. (I hope this won’t take us too far off topic. Ignore this if so.) I ask because it was reading that book that made me realize that I wasn’t a socialist in any very strong sense. (I think there are weak enough senses in which I’d still qualify, but I’m not sure how useful that sense is in most cases.)

Matt 09.01.09 at 4:32 pm

god-damned comment moderation. Can’t you please do something about this? Surely there must be a better way. (I know I could try to remember, but I’ve never seen another blog so bad about this word, especially one where it’s so relevant.)

Salient 09.01.09 at 4:41 pm

The problem with a camping analogy is that we often go camping with family or self-selected friends that we treat as kin or close to kin.

That doesn’t quite obtain in his other non-camping examples, e.g. a rescue operation when a building goes up in smoke. The interactive behavior we see there does not rely upon some pre-established notion of kinship.

Our brains are, to a crude first approximation, wired to find and establish kinship relations with the people around us. We learn from our society who is and is not “kin” according to rather arbitrary rules — rules which are mutable and (this is important to me) education-dependent. This not only makes friendship possible, but (when amply and appropriate developed) allows a human being to relate compassionately to the other human beings in her/his midst. Put more simply, you are not my brother-kin because I have learned to not regard you as my brother-kin, not because of any inherent characteristic of you or of me.

Put another way, what’s stopping me from learning to recognize you as a distant kin? I don’t have to deeply connect with you; I just have to have some feeling of communal obligation to serve you when you are in need of my service, together with some sense of joy when I do successfully serve you.

This idea bears further discussion and I look forward to it here. Surely my crude point needs a lot of refinement… must go teach, but I am looking forward to this thread!

Kieran Healy 09.01.09 at 4:44 pm

OK, you can say it now.

Substance McGravitas 09.01.09 at 5:00 pm

Socialism socialism socialism!

Chris Bertram 09.01.09 at 5:11 pm

Testing socialism!

Chris Bertram 09.01.09 at 5:12 pm

You see, “socialism” works … once the technical obstacles are overcome.

Substance McGravitas 09.01.09 at 5:13 pm

Sure, it’s fine for the elite.

bob mcmanus 09.01.09 at 5:30 pm

The problem with a camping analogy is that we often go camping with family or self-selected friends that we treat as kin or close to kin.

boy/girl scouts, militaries, archeology/paleontology expeditions, many other examples

That some of these might be “self-selected” or initiated toward a common particular social purpose I think is not a serious objection.

Martin Wisse 09.01.09 at 5:36 pm

ITYM the vanguard…

I don’t know Cohen and I made my choice already, but this does sound like an interesting book. Will keep an eye out for it.

ingrid robeyns 09.01.09 at 6:05 pm

I hate posts like this, where intersting books are discussed which we, ordinary inhabitants of the Low Lands, cannot buy. Still, a nice person sent me an electronic copy of (a draft of?) the book, so I have access to the content, I suppose. ONly not the smell and the feeling of holding the book. And the “cover”:http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/images/0691143617/sr=8-1/qid=1251828166/ref=dp_image_0?ie=UTF8&n=266239&s=books&qid=1251828166&sr=8-1 ! What a beautiful cover! Harry, you should have made a link to the picture of the cover. I’ll buy it as soon as it’s on sale here.

Since all you socialists are reading this thread: whatever else theoretically or philosophically has there been published on socialism in recent years that we need to read?

ingrid robeyns 09.01.09 at 6:06 pm

haha, mine in moderation too… it’s probably because I implicitely denied being a self-identified socialist?

Matt 09.01.09 at 6:13 pm

That’s wonderful Chris.

SamChevre 09.01.09 at 6:26 pm

My argument would be that kin-like relationships aren’t infinitely scaleable.

JoB 09.01.09 at 6:38 pm

Socialism!

(sorry, I just needed to have a try – by the way, Harry: you convinced me, I’ll buy when I can)

Harry 09.01.09 at 6:38 pm

Aha! Done, Ingrid!

JoB 09.01.09 at 6:39 pm

Nope, soc1al1sm it still has to be for me. But if you wait long enough you’ll find a very, very interesting post just one (or two) up from this one.

Scott Martens 09.01.09 at 6:52 pm

Small coincidence, I found this quote today, from The German Ideology:

“Philosophy and the study of the real world have the same relation to one another as masturbation and sex.”

I’m thinking of using it in my thesis.

chrismealy 09.01.09 at 6:52 pm

It’s too bad seeing Gintis being so hard on Cohen. Gintis has spent ages trying to develop the very hypothetical social technologies that Cohen wants — Bowles and Gintis on education, their work developing the theory of the democratic firm, and their recent stuff on reciprocity.

For laughs check out Gintis debating Mark Levin’s fans (a right-wing talkshow host I’d never heard of before).

Neel Krishnaswami 09.01.09 at 6:59 pm

You have this backwards, I think. Forming peer-groups is automatic (and malleable), as you say, but most people will never be in our peer group, due to the limits of time, presence, and memory. Treating people outside our peer group as real is a skill we learn; it’s not innate. That’s why the pattern of compassion towards members of the in-group, and cruelty for the out-group, is pervasive throughout human society.

Universal morality is a learned generalization, and is not naturally in tune with our emotional responses. Adam Smith, in The Theory of Moral Sentiments observed that the real distress a typical Englishman would endure because of having his finger injured would be greater than if he were to learn that everyone in China had died the night before, because the Chinese people are not in the immediate emotional social circle of the Englishman, and so he cannot grieve their deaths the way he would grieve the death of a friend or family member.

However, if there were some way to avert that disaster at the price of one’s own life, most people who have learned morality would not hesitate to pay that price. But this response is a learned response: we have to be taught to imagine feeling the sympathy we naturally feel towards friends and family to outsiders, and then taught to rationally extend the sympathy we feel for kind and friends to people who are beyond the horizon. How to cultivate and strengthen this unnatural response is pretty much the central problem of practical morality.

Chris 09.01.09 at 7:08 pm

boy/girl scouts, militaries, archeology/paleontology expeditions, many other examples

That some of these might be “self-selected†or initiated toward a common particular social purpose I think is not a serious objection.

I think it’s a very serious objection. Historically, the biggest obstacle to sozialism has been resentment of “welfare queens” or the equivalent. The salient characteristics of a welfare queen (other than mythicality) are that she is (1) undeserving, and (2) Not Like Us in some unspoken, but readily understood by the audience, way. Ingroup members may get unconditional help, but outgroup members are suspected and begrudged even the most necessary medical procedures, crumbs to the starving, etc.

If we could figure out a way to get people to see all humanity as the ingroup, then IMO sozialism would find much less resistance (at least, the sozial democratic welfare types, not necessarily an actual command economy, but who really wants that anyway).

So the experience of going camping with ingroups doesn’t say much.

Chris 09.01.09 at 7:09 pm

Oops – first two paragraphs should both be italicized as a quote. Software must auto-terminate style at the end of the paragraph or something…

Salient 09.01.09 at 7:11 pm

Forming peer-groups is automatic (and malleable), as you say, but most people will never be in our peer group, due to the limits of time, presence, and memory… How to cultivate and strengthen this unnatural response is pretty much the central problem of practical morality.

I think we’re in loose agreement, but I will insist that “peer group” is not the same as “kin” — for example, I have hundreds of “kin” but a peer group of maybe eleven or twelve people, and the two don’t really coincide. Surely you agree, for example, that it’s possible for two individuals to regard each other as “kin” despite never having met. Not true for peer groups (or at least it wasn’t true before the Internet, but that’s a whole different story).

Ben Saunders 09.01.09 at 7:21 pm

You mention the comparison to Frankfurt’s ‘On Bullshit’ – which was simply an essay republished as a book of its own that cost almost as much as his collection (The Importance of What We Care About).

Is this also true of Cohen’s? That is, is it the same text as printed here:

Ed Broadbent (ed.) Democratic Equality: What Went Wrong?

Harry 09.01.09 at 7:29 pm

Without comparing them page-by-page I’d say not quite the same but very similar (he acknowledges this at the end of the book).

bob mcmanus 09.01.09 at 7:48 pm

27:If we could figure out a way to get people to see all humanity as the ingroup, then IMO sozialism would find much less resistance (at least, the sozial democratic welfare types, not necessarily an actual command economy, but who really wants that anyway).

Umm, me? Or at least a much much bigger share of the economy being “commanded” including health care, transportation, energy, finance, maybe communication networks tho not content.

The “common social purpose” is/was of course the important challenge, and we have enough examples of societies achieving that at least temporarily, that I do not consider it an insurmountable difficulty. There will remain free riders and out-groups, but they will be defined and determined by the common purpose so as to enforce and broaden solidarity rather than divide.

Pyramids, Chartres, WWII. This isn’t a utopian fever dream. Carbon-free economy, anyone?

bianca steele 09.01.09 at 7:54 pm

@28: I think they’ve got some kind of complicated post-processing turned on that’s attempting to remove and then re-insert formatting tags (can’t remember what I was trying to do when I decided that was probably the problem) in a script or something that doesn’t understand recursive inclusion of one tag inside another very well.

Harry 09.01.09 at 8:15 pm

I’ll try to respond to Matt when I’ve cleared out my work (that’s not a very satisfactory promise). But Eamonn’s comment reveals what I was like back then, and perhaps hints at why my reasons for not regretting what I did are such good ones….. (I’m sure this is no surprise to you, Eamonn!)

Enzo 09.01.09 at 8:16 pm

Brian 09.01.09 at 8:54 pm

boy/girl scouts, militaries, archeology/paleontology expeditions, many other examples

So the socialist paradise will look like the military?? I think maybe I’ll pass…

And I’m not really sure that counts as “communal property”.

As an outdoorsy-overnight-without-a-mattress-or-sometimes-even-a-tent kind of guy, it actually doesn’t strike me as the best way to run a camping trip, although yes, a less than complete amount of communal property and planned mutual giving are quite nice.

Jef Gleisner 09.01.09 at 9:02 pm

Should we really be looking to philosophers for suggestions as to how human societies might be

better organised ? If I understand Gerry Cohen’s last major philosophical work correctly, the answer is ‘no’. What will sadly be his last book, sounds like the kind of story, some members of a Russian obshchina might have been telling themselves 100 odd years ago, when they got into their crazy heads to try to refashion the whole world in the image of their face-to-face place of abode.

Patrick S. O'Donnell 09.01.09 at 9:05 pm

Re: whatever else theoretically or philosophically has there been published on socialism in recent years that we need to read?

Ingrid,

I could–and would be delighted to–be mistaken, but I don’t think there’s been much published on socialism in recent years, let alone that we need to read. Not long ago I put together a “very select bibliography” (constraints: books only, in English) for Marx and Marxism that includes about a dozen or so titles on socialism that are theoretically or philosophically substantive. It is found here (click on ‘Marx & Marxism’ in the body of the post): http://ratiojuris.blogspot.com/2008/12/marx-marxism-very-select-bibliography.html

(For what it’s worth, I think all of the volumes in the Real Utopias Project should also be read by anyone interested in the theory and praxis of socialism.)

In the above list, I think Michael Luntley’s book has not received the attention it deserves and perhaps the same could be said of David Schweickart’s work.

Patrick S. O'Donnell 09.01.09 at 9:07 pm

I used the “s” word in my post awaiting moderation.

Salient 09.01.09 at 9:23 pm

Is this also true of Cohen’s? That is, is it the same text as printed here:

Yes, it’s a “revision” of an older essay (probably the one you mention). In fact, I can guarantee it because it says so in the back of the book :-)

Henri Vieuxtemps 09.01.09 at 9:31 pm

So, if the group has to be small, is social1sm possible on a small scale, in a village, as a coop, kibbutz, or something? And if it is possible, then at some point, with, say, a few thousand people involved, shouldn’t it be enough? Why do you care how other communities are organized; just find one that suits you.

Chris 09.01.09 at 9:31 pm

@32: I think we may have slightly different definitions of “actual command economy”. I think the free market often stinks at setting goals, but can be good at finding efficient ways to achieve a particular goal.

So I wouldn’t call something like, e.g., the Canadian health-care system a “command economy” since the government only specifies what to do, but allows private sector actors to compete at actually doing it — while the British one sort of is (except that buying additional care on the free market is also allowed).

Similarly, while I think government should regulate the quality of food that is allowed to be sold, and mandate disclosure of nutrition information, etc., I don’t think it should actually own and operate farms and food processing plants. I think the efficiencies of means discoverable by the free market outweigh the added cost provided by profit-taking and the private sector’s higher cost of capital.

But maybe you disagree, at least for industries that provide utilities and other necessities of life. Upon rereading, my tone in that parenthetical seems rather dismissive, and I apologize. Other people do, after all, have other points of view about things.

bob mcmanus 09.01.09 at 10:16 pm

From the link in 38, which is worth following:

“It may be thought that with the recent collapse of the Soviet Union, Marx’s socialist philosophy and economics are of no significance today. I believe this would be a serious mistake for two reasons at least. The first reason is that while central command socialism, such as reigned in the Soviet Union, is discredited–indeed, it was never a plausible doctrine–the same is not true of liberal socialism. This illuminating and worthwhile view has four elements:

(a) A constitutional democratic political regime, with the fair value of the political liberties.

(b) A system of free competitive markets, ensured by law as necessary.

(c) A scheme of worker-owned business, or, in part, also public-owned through stock shares, and managed by elected or firm-chosen managers.

(d) A property system establishing a widespread and a more or less even distribution of the means of production and natural resources. (On these features, see John Roemer, Liberal Socialism [Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994])

—John Rawls”

I’m sorry, but looking around our current neoliberal oligopoly, with trillions to investment banks and nothing o far to healthcare, the fantasy of d) being derived from the first three, especially a) noted as considered ethically primary, is why I find left-liberals and especially John Rawls, more than a little absurd. Point d) should be both temporally and morally primary we should not try to adjust socialism to fit liberalism, but adjust liberalism to allow socialism.

I am also seeing quite a few recent Marxian books in my library, although many of them have more to do with Gramsci. The reasons for this may be for a different post.

Finally, it was a great joy for me to see at Mark Thoma’s, after a post discussing JS Mill’s foundations of social science in positivism, to see a group of continental commenters come round to mention an alternative tradition derived from Schlegel. Love these internets.

alkali 09.01.09 at 10:25 pm

As regards the various links — When will the proletarians not logging in from .edu domains rise up and throw off the chains of JSTOR? This is the internet, damn it: all the ice cream should be free, and delicious.

peter 09.01.09 at 10:50 pm

“had I not gone to LA when I did, and developed the way I did, I’d not have met my wife and had my kids. “

Au contraire, you have no proof of this claim, nor could you have. Had you chosen not to go to LA, or not to go when you did, you may well have met the same woman somewhere else, still married her and still had your kids. You could even have met her and married her on the very same days that you did meet and did marry her, only elsewhere.

It is completely consistent with our life experience that our fates are pre-determined, as random as they look, or (less strongly) that the final outcomes of our lives are independent of the decisions we make during their course (ie, the pinball machine theory of life: that the ball always ends up at the bottom of the tray, regardless of what plays we make during the game or how long we play).

John Quiggin 09.01.09 at 11:10 pm

All things in moderation, including socialism, and, sadly, this comment.

Joshua Holmes 09.02.09 at 12:50 am

because some economists had invented clever ways of harnessing and organizing our capacity for generosity toward others.

Charity is a fine principle, but it doesn’t extend very well to building furniture or farming oats. Once again, you need a New Soviet Man for that sort of thing, and that went rather badly last time.

Mario Diana 09.02.09 at 1:07 am

There are several posts that note that the kind of meaningful empathy that seems a prerequisite to the success of socialism seems to extend from an individual only to those in his or her immediate circle, and that we are perhaps “wired” that way. And so, once again, the only thing needed to effect socialism is to transform human nature.

engels 09.02.09 at 1:23 am

People have been calling it the “camping trip†book; he uses the conceit of a camping trip to demonstrate that organizing social life around the two principles that, for him, define socialism – a very stringent version of equality of opportunity, and a very demanding principle of community – is very appealing to most people in some circumstances.

Who has ever organised a camping trip around a principle of equality of opportunity?

I’m not the world’s biggest camper but I have been on a few and I’ll admit being pushed to think of examples of when ‘equality of opportunity’ seemed to be an issue–either consciously or unconsciously–for anybody.

I think I have a rough idea of what is being talked about here, and I take the point that on a camping trip people share their stuff, help out with the chores, there’s no buying or selling, people co-operate and fulfill themselves by themselves and with others, and so on. Great. So far so nice and socialist as far as I’m concerned. But ‘equality of opportunity’? Where does that come in? ‘You’ve had your ten minutes in the shower–I don’t care if you haven’t finished–it’s my turn now?’ Or what?

Zarquon 09.02.09 at 1:27 am

Charity is a fine principle, but it doesn’t extend very well to building furniture or farming oats.

Of course it does, most farmers in the west are subsidised.

Nick 09.02.09 at 2:37 am

I find it conceivable that we may one day develop this dramatic new moral sense and leave behind current ways of co-ordinating action. But I doubt such a sense will be developed through aggressive state intervention as Marxists (originally?) thought. And I don’t think such a theory can guide any useful actions for changing contemporary politics where notions like maintaining the rule of law and a productive market order are rather more pressing. It may guide individual actions in new and interesting ways.

Joshua Holmes 09.02.09 at 2:50 am

Rent-seeking != charity

Yarrow 09.02.09 at 3:56 am

ingrid robeyns: whatever else theoretically or philosophically has there been published on s…..ism in recent years that we need to read?

He’s an anarchist rather than an s-wordist, but David Graeber is both smart and funny. I’d recommend Possibilities: Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire; if you like that, then Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of Our Own Dreams is longer and chewier (and engages with Marx much more directly).

bob mcmanus 09.02.09 at 4:21 am

the only thing needed to effect socialism is to transform human nature.

A perfect misunderstanding of socialism and Marx.

Was the end of chattel slavery a matter of a change in “human nature”? Did half the white population change biologically while the other half did not evolve? Just silly. Chattel slavery, like most manifestations of human” nature” was a social construct, ended in theory by a war and some amendments. But we are not yet to Marx, who would ask why that war at that time ended that institution. IIRC, he gave a wrong answer at the time, but he understood the right questions.

Chris Bertram 09.02.09 at 5:15 am

The following words from the Gintis review seem worthy of comment, and perhaps of a post at some later stage:

bq. Everyday observation, reinforced by a huge body of empirical evidence—see my book, Bounds of Reason (Princeton, 2009) for details—that unless there are safeguards against the free-rider tendencies of the selfish, the natural tendency for the majority to cooperate will be undermined, and cooperation will unravel. Moreover, the larger the group, the harder it is to identify and punish the free-riders, even though most people are willing to incur personal costs to do so. Markets work because they discipline firms, who then discipline workers, thus solving the free-rider problem.

Cf also the mentions of “welfare queens” etc. in the Holbo McMegan thread,

Much of the commentary that we read is produced by people with satisfying careers who think insufficiently of the lives of the people who produce the material and service goods they consume. Those people often work long hours in unsatisfying jobs (indeed they are “disciplined” by markets and firms to do so) at the expense of realizing their full human possibilities. (Does this sound familiar?) And they are still better off that those who are excluded from the labour market, the unemployed, some of who — other poor people — get stigmatized as “welfare queens”, “free riders” etc.

One might say, and not only rhetorically, that the real free riders, who benefit from the toil of others, and from a system that coerces others to toil are those whose ownership of the means of production exempts them from the burden of labour, and those who are employed on fat salaries (McMegan, Jonah Goldberg, half of academia) to produce guff berating “welfare queens” etc.

As I said above, I haven’t yet received my copy of Cohen, but I did watch his “against capitalism” broadcast from the 1980s the other day. The way that capitalism gets millions of people to endure unsatisfying work for most of their lives for little pay was central to that critique, as it was to Marx’s.

ingrid robeyns 09.02.09 at 7:16 am

Patrick @ 38: thanks for this! One day I am going to steal this picture of Marx from you and put it on CT, perhaps as a Sunday picture, purely esthetically of course.

I am a great fan of the Real Utopias Books, yet don’t consider all of this as ‘socialist’. But perhaps the proposals made there are as close to the the ‘second best socialism’ (about which Cohen also talks) that we can get. So perhaps I am a socialist after all, but only a ‘second best socialist’ :-)

dsquared 09.02.09 at 7:22 am

And they are still better off that those who are excluded from the labour market, the unemployed, some of who—other poor people—get stigmatized as “welfare queensâ€, “free riders†etc

who are in turn better off than people working in factories in China … the fact that so very goddamned many people are required to be paid in jobs loosely definable as “disciplining the workers” (which includes people charged with producing homilies aimed at making the overseers feel good about themselves) really does look like the sort of thing that a technological fix ought to be available for, and ought to be welcomed if it were invented.

alex 09.02.09 at 7:37 am

Before we get the technological fix, we do have to get the anthropological one – to make people stop wanting to have more stuff than others.

Uncle Billy Cunctator 09.02.09 at 8:14 am

“So, if the group has to be small, is social1sm possible on a small scale, in a village, as a coop, kibbutz, or something?”

I’ve heard others tell me that in the corporate world, groups need to stay under 150 to “perform” well. No clue if this has been confirmed by research or what “perform” means.

The first kibbutz started with just a handful. My kibbutz, considered the first real kibbutz, started with around 200, but the population fluctuated significantly due to malaria before the swamps were drained. It is one of the few kibbutzim that still function. Before we left, everything was still fairly communal, but provided for everything and there was room for a cash allowance to boot for discretionary spending. They “privatised” the food at one point and as a result almost no one showed up for dinner at the communal dining hall. Breakfast and lunch was still fairly popular, so they continued to serve meals. The big decision these days is to begin to pay salaries commensurate with jobs. Of course most of those who have positioned themselves are pushing for it, but really the place is run by a group “The Parliament” that will reap all the benefits for themselves and their families as they have been doing quietly all this time anyway.

They have a very successful high tech factory. Same situation… some have positioned themselves for privatisation in the near future. As it is now, there is a huge layer of management, most of whom really don’t do much at all… and then almost everyone else is either a paid outside employee — engineers, administration, assembly people.

As is the case with almost all of the kibbutzim, they would never have lasted as long as they did without heavy government subsidies. Those that developed successful factories and then broke up are basically nice little factory towns now. Plenty of corruption is often involved in the sale of the property and means of production.

I always saw the problem as: Kibbutzniks will always want to leave or live in a non-egalitarian fashion as long as they have the opportunity. No option to do this, then no problem exists. My big dream was always to be able to order a pizza at any hour, but when we went out to eat pizza, it tasted that much better. Now, in the city, it’s no big deal, and of course the pizza is just ok unless you’re really hungry. A simple view, but maybe important.

antoaneta dimitrova 09.02.09 at 8:52 am

Without the training in core philosophy or reading the Cohen book (apologies), just want to draw your attention to two features of socialism which are rarely recognized by those who have not experienced it:

-socialism as it existed in Eastern Europe was, indeed, founded on the premise of ‘a property system with more or less even distribution of resources’ , or, as one commenter said, everyone being ready to accept they did not need more stuff than others. This led to a rather perverse consequence, that when human beings had the impulse to act less than perfectly, not always recognizing everyone else in society as kin, such impulses were not acceptable in the context of the socialist ideology. Thus society was permeated by a deep hypocrisy as everyone learned (also because of other, better known characteristics of oppressive totalitarian regimes) never to say what he or she really thought. To summarize rather crudely, because it assumes that we will all be altruistic and accept equal distribution of resources, socialism makes people hypocrites ( or, if you prefer, state intervention to support this idea does). A hypocritical society soon leads to all kinds of injustice.

– Being able to accept socialist principles is not simply about needing less stuff. The idea of equal distribution of resources and equality of opportunity also meant equal recognition and rewards for less or no work. This very soon led to a negative learning process in anyone who aspired for excellence in a non-material sense. Doing your work better than others was simply not necessary as everyone would get the same reward anyway. In this way, rather conscientious and excellent people started shirking at work, as they knew their efforts to be excellent would not be rewarded. To this very day the working ethic of people who have lived under socialism is appalling. All this to say that the technology to make socialism work may never be available. And indeed, as Brian @36 said, socialism was like being in the military.

Sorry for the long comment: in the end, a question: I wonder how Harry and the rest of you think that socialism, even in the abstract sense, can be compatible with liberalism’s aspect of free choices for the individual?

JoB 09.02.09 at 10:10 am

Thanks to the link in 30 I could read the book I cannot order yet. And despite Harry’s excellent efforts I have decided not to buy it when I can order it.

On reflection I think Harry quoted Cohen defeating the point of his book: “I’m not outdoorsy, or, at any rate, I’m not outdoorsy overnight-without-a-mattress-wise.â€

Taking the analogy to heart there first is the choice to go camping and then there is camping. In the extension Cohen makes in the latter chapters that choice is no longer there. It is replaced by a promise. Taking it back to the analogy it’s maybe something like the father saying: “It will be a lot of fun, son. I did it with my father. Didn’t want to go at first but loved every minute of it. It is a life-changer.” – but with the son fleeing the communal site during the first night (to be eaten by a pack of wolves or some such typical camping horror I had the fortune never to be forced into).

Or as Patrick @ 38 has it:

we shouldn’t try to adjust soz1alism to fit liberalism, but adjust liberalism to allow soz1alism.

Which is I think exactly capturing Cohen’s point (even if he would argue it doesn’t but it is very possible that even eminent people have it wrong when they think they have it right – in fact, it is specifically when eminent people think they have it right that they are getting it wrong). As he’s saying himself (I can’t cut and paste from the google website): it’s about ‘design’, the technology ha’s looking for is not the technology of dsquared @ 57 but the technology that will allow to go for a good design without the drawbacks of central planning.

It’s the Soviet Union but then in an economically prosperous version

That’s not good enough. Liberalism comes first – and I’m sure it is our best bet to discover some technology (like the one we’re using now) that allows people to share without worrying about an emotion they like when they gamble and win.

mpowell 09.02.09 at 11:26 am

The technology you are looking for must be something amazing indeed. I can only speak for myself, but it is difficult to imagine people functioning in a modern economy without a strong profit motive and that is true even for those people with fullfilling jobs. I work as an engineer and, generally speaking, I like the work that I do. But it is such a meaninglessly small piece of the total work of making the world a better place that it is very difficult to imagine feeling motivated by the idea that I am helping people out by doing my job better. You put me on a fixed income scale and I will be significantly less productive while I spend more of my energy pursuing other interests.

I would like to see what an better version of a regulated market economy looked like before I started worrying about social1sm. By the way Bob @ 32, your list doesn’t really sound like much of a command economy to me. Finance would obviously be a big change, and risky, but since it is pretty obvious that that sector is extracting a pretty huge surplus without delivering much obvious benefit, that it wouldn’t be unreasonable to try shifting that to the public sector, even for a garden variety liberal. There is a lot more to a command economy than just what sectors are owned by the government anyhow.

Mike Otsuka 09.02.09 at 11:50 am

Jerry’s own estimate was that this version of his essay was about “30% different” from the previously published version.

At the time of his death, Jerry had plans and papers for future publication, which I’ll be looking after now.

alex 09.02.09 at 12:35 pm

I think my problems with any kind of social1sm that is not libertarian – i.e. anything with a command economy – comes from a simple observation. Go to a store that sells magazines, look at all the different hobby publications on offer, flick through them and see all the small-ads: people making a living just doing stuff that amuses other people, offering little widgets and gizmos, entire social universes of people who “under social1sm” either have to be allowed to carry on doing what they do, or forced to do something else. Then try to scale that problem up – how many hundreds of thousands are employed in sales & marketing, advertising [ick!], or even in manufacturing umpteen-dozen essentially similar types of mobile-phone/toaster/iron/whatever… Does anyone really think that they can literally take charge of the economic processes involved here, and turn them to other purposes, without massive disruption, immiseration, resentment, unrest and [unfortunate, regrettable, proportionate] repression?

Market economies are, whether one likes it or not, really good at forcing people to do things without giving them someone to hate for it. In a non-market economy, everyone will know who to hate.

Patrick S. O'Donnell 09.02.09 at 1:02 pm

Bob @ 54:

Yet Marx did rely on anthropological and psychological presuppositions and assumptions about “human nature” as, of late and in different ways, both Martha Nussbaum (in Frontiers of Justice, 2006) and Jon Elster (e.g., in Making Sense of Marx, 1985: 61-92, and his essay, ”Self-realisation in work and politics: the Marxist conception of the good life,’) well appreciate. For a helpful discussion of Marx and his conception(s) of human nature (in addition to the first Elster reference above), please see W. Peter Archibald’s Marx and the Missing Link: Human Nature (1989).

Ingrid,

I agree with your remark with regard to most of the Real Utopia volumes. A nice introduction to the sorts of topics that need to be treated under this rubric of ‘second-best socialism” (e.g., ‘market socialism’) that many folks might not be aware of is Diane Elson’s article, “Market Socialism or Socialization of the Market?” in New Left Review, 172 (November/December 1988): 3-44.

Patrick S. O'Donnell 09.02.09 at 1:15 pm

I suppose I’m a bit hard-headed: I used the “s” word again.

Mo MacArbie 09.02.09 at 2:04 pm

Doing your work better than others was simply not necessary as everyone would get the same reward anyway. In this way, rather conscientious and excellent people started shirking at work, as they knew their efforts to be excellent would not be rewarded.

But then doing a job well can be its own reward (says the guy commenting from work). I’m generally a happier person when I’ve worked efficiently all day than when I’ve shirked. And then there’s that bit from Ivan Denisovich where Ivan deplores the masonry of the prisoner who laid the previous section of bricks for the prison wall, and his essential humanity asserts itself as he proudly evens it out with his addition.

And my ma13 enhanc3nemt aid will be called Publica.

Chris 09.02.09 at 3:17 pm

@64: ISTM that the solution to that problem is taxation. Do whatever you want, but pay your taxes which are used for this list of public purposes.

The government doesn’t even need to build its own buildings – it just needs to plop down a pile of tax money and say “Whoever builds this building in such a way that it passes these standards gets this money” and let the efficiency-seeking ingenuity of the private sector find the best way to actually build it.

Another (probably unoriginal) idea I think might have some promise is to modify the laws governing corporations so that some specified share of the profit, instead of accruing to the benefit of the capital shareholders, must be distributed to the employees (equally divided). This would undermine the usefulness of underpaying your employees as a business strategy, since some of the profits so obtained have to be paid right back to the same employees. (This split would of course take place *before* the shareholders’ agent determines whether to pay out the profits as dividends or retain them to pay for expanding the corporation, mergers, etc.)

Increasing the return to labor and limiting the return to capital would be highly beneficial to society, IMO. Rentiers are not useful members of society. (Also: higher inheritance taxes. It’s not only truly unearned income, but also the one tax that can’t have a distortionary influence on behavior because the event taxed isn’t voluntary.)

But none of these ideas is sozialism as I understand it (although they would certainly be demagogued as such, but you can hardly rely on demagoguery as a guide to reality).

Alex 09.02.09 at 3:22 pm

Eastern Bloc regimes never seemed to have much trouble motivating some groups of workers to go beyond the call of duty; specifically, secret policemen, border guards, and censors seem to have put in a lot of time without making a profit. Well, without *officially* making a profit – but it was quite rare that they made a profit by doing what they were supposed to be doing, rather than subverting what they were doing officially. And a hell of a lot of ordinary citizens made quite a lot of effort to help them spy on their friends, for surprisingly little material reward.

This isn’t as shallow as it sounds. Clearly, it was possible to motivate people; it was done. The problem was that so much of this labour was allocated to evil and usually fairly unproductive aims, and that this actually went up over time.

K. Williams 09.02.09 at 3:58 pm

“Those people often work long hours in unsatisfying jobs (indeed they are “disciplined†by markets and firms to do so) at the expense of realizing their full human possibilities.”

Absolutely. But the vast majority of people worked long hours in unsatisfying jobs in the Soviet Union and the Eastern European countries, too, and worked long hours in unsatisfying jobs in pre-liberalization China, on top of which they were in slow-growing economies, had no political freedom, and no opportunity to meaningfully improve their own living standards by working harder or coming up with a great idea. It’s not entirely clear that’s a better alternative. And unless you think that inequality is per se a bad thing, the fact that Gintis is well-paid to write what he writes while others toil isn’t really a strike against the system as long as the toilers are better off than they would be under some alternative system — although I’m all in favor of coming up with a technological fix to keep people from spending their days in miserable jobs.

alex 09.02.09 at 4:00 pm

Chris – good points, but then we’re not talking about the kind of social1sm that one gets ‘under’ – merely social democracy as it functions, more or less, in western Europe; so where’s the beef?

BTW, it isn’t ‘rentiers’ any more, it’s ‘savers’, who are apparently an entirely innocent breed…

Sebastian 09.02.09 at 4:19 pm

“Well, without officially making a profit – but it was quite rare that they made a profit by doing what they were supposed to be doing, rather than subverting what they were doing officially. And a hell of a lot of ordinary citizens made quite a lot of effort to help them spy on their friends, for surprisingly little material reward.”

They sometimes did it out of fear and often did it because they could gain power over other people.

Chris Bertram 09.02.09 at 7:58 pm

#70

1. The point I was making about free riders giving lectures on the importance of disciplining free riders doesn’t depend on any such comparison for its truth.

2. Whatever the general benefits that capitalism brings, it can hardly be denied that it has a systemic propensity to use labour-saving innovation in ways that don’t relieve workers of the burden of labour.

wolfgang 09.03.09 at 6:36 am

Perhaps I should read the book to better understand why I hated camping trips as a child. If camping really is just a (disguised) incarnation of socialism it might explain a lot.

Tim Wilkinson 09.03.09 at 10:58 am

Tim Minchin – If I Didn’t Have You (or Just the Lyrics)

Back on the core topic, I haven’t yet read the book, but:

1. Democratic So-shall-he-zoom (at least of a 2nd-best variety) doesn’t necessarily depend on individual cooperative tendencies in daily life – just the willingness to vote for a system on the basis of mature reflection – almost a kind of Odyssean tying-to-the-mast kind of commitment.

2. Depending on what you mean by So-shall-he-zoom, presumably the point some are making is that free-riding (not to be confused with widespread choice of leisure over other goods _per se_) might, via the prisoner’s dilemma, give rise to – aaargh! – one of those suboptimal outcomes (as opposed to one of countless incommensurable Pareto-optima). That could as necessary be dealt with by non-private-market incentive structures – insofar as those are considered compatible with So-shall-he-zoom, of course.

3. Only if that is not possible for whatever reason does the issue of ‘human nature’ (which we of course know all about now – as according to some did Adam Smith) arise. And before we even get to altruism such things as public service ethoi, professionalism and the enjoyment of work well done come into play (mpowell – have you considered a career change?). These are all routinely frustrated by management under capitalism, at a terrible cost in demoralisation and (I’m going to say it) alienation.

The ‘profit’ (or ‘wage’ as we proles call it) motive needn’t be replaced by some kind of permanent Dunkirk spirit for for people still to go to work. _Maybe_ people don’t work as hard if they don’t have payment by results (as most don’t really).

But first, that isn’t necessarily a problem – presumably (by the economists’ own logic) they benefit from not working so hard. Hard work never killed anyone, they say – but as the standard retort goes, it has crippled millions, and long hours on the career-advancement treadmill affect families, etc etc.

Furthermore, if one has to be at work, it is much more pleasant to immerse oneself in something interesting and challenging (not of course in the management-speak sense synonymous with ‘gruelling’) [edit: @67 makes same point]. Skiving (without detection) can actually be as hard and stressful as getting on with the job – and often makes the day go more slowly, which most people – Dunbar in Catch-22 excepted – do not relish, and regard as an indicator of not having fun.

If jobs were chosen by satisfaction (which is plausibly well-correlated with aptitude) rather than remuneration, a lot of people would probably be happier and more productive – and it’s noticeable that the best paid jobs are largely more fulfilling, enjoyable and high-status, though the last of those is certainly not independent of pay/profit levels, given the money-fetish that’s currently prevalent. Of course we still need those toilet-cleaning robots, too.

4. Even if routine impersonal altruism were required by So-shall-he-zoom, I’m not convinced that it isn’t possible to foster such an outlook (in the relevant sense) through education/socialisation, and without Strauss/Ingsoc/McCarthy- style mythmaking. Though there is considerable potential for extreme creepiness there of course.

(Before anyone else is rude enough to point it out, I do realise that ‘So-shall-he-zoom’ as punny substitute for the S-word fails in a number of ways, including being irritating, inadequately homophonic, and of at-best-tenuously relevant content. That bold experiment at least has failed.)

Tim Wilkinson 09.03.09 at 11:12 am

Also failed because ‘socialisation’ is of course banned too. Doh. Sorry Mod.

Salient 09.03.09 at 1:33 pm

Before anyone else is rude enough to point it out, I do realise that ‘So-shall-he-zoom’ as punny substitute for the S-word fails in a number of ways,

On the contrary, I was quite pleased by it. But then, I am also irritating, inadequately homophonic, and at-best tenuously relevant. :-)

Maybe people don’t work as hard if they don’t have payment by results (as most don’t really).

Yep. And we can probably get by as a species working less hard than we do, if we share resources according to a reasonable scheme. People can work a little and get by with the basics, or work ‘more’ and get more luxury goods. Taking leisure time to be a luxury good, we can envision some rough equality of satisfaction resulting. So-shall-he-zoom, in its intuitive form, is just not that hard to comprehend as an appealing ideal.

JoB 09.03.09 at 1:43 pm

So-shall-she-zoom – much better!

That’s maybe the technology we need: an effective way of presening leisure time as an ultimate luxury good.

PS: maybe even better: so-shall-(s)he-zoom, ’cause we want equality of zoom, don’t we?

Jonathan Derbyshire 09.03.09 at 2:12 pm

An extract from Why Not Socialism? appears this week in the New Statesman: http://www.newstatesman.com/uk-politics/2009/09/camping-trip-others-community

SamChevre 09.03.09 at 2:14 pm

So, if the group has to be small, is social1sm possible on a small scale, in a village, as a coop, kibbutz, or something? And if it is possible, then at some point, with, say, a few thousand people involved, shouldn’t it be enough? Why do you care how other communities are organized; just find one that suits you.

Yes, small-scale socialism/social provision is pretty common–Hutterites, kibbutzim, and many extended families are fairly strong-form and many of the Plain people generally are weak-form socialist.

Read Red Family, Blue Family by Doug Muder. The Red Family model is a lot more socialist. Basically, liberal values–self-ownership values–at the state level tend to damage the small-scale socialisms.

Which is why I’m in favor of political liberalism/libertarianim/minimal government. I think it strengthens the workable small-form socialisms.

bianca steele 09.03.09 at 2:17 pm

Tim W: If jobs were chosen by satisfaction . . . toilet cleaning robots

A.S. Byatt makes the same point in Babel Tower, I think fairly definitively. Socialism doesn’t work because nobody likes to clean toilets. (I can’t persuade myself to agree with Ursula Le Guin that “making order where people live” is sufficiently satisfying when that means cleaning their toilets.)

John Protevi 09.03.09 at 2:30 pm

If “Dan” and “Joshua Holmes” from the “Rationing Again” thread are still around, K. Williams @ 70 is a good example of using “actually existing socia!ism” as a millstone to hang around the neck of the left. That’s the referent of the allusion I was attempting with “actually existing libertarianism.”

alex 09.03.09 at 2:45 pm

I’m still confused here, some of the commenters seem to be saying that ‘social1sm’ = ‘France’. Is the argument then over whether that’s a good or a bad thing?

Meanwhile, Tim, I think your plan falls down at the first hurdle. If zooming requires “the willingness to vote for a system on the basis of mature reflection”, how can we ever hope for that to happen? Especially since ‘vote’ actually means ‘acquiesce in a major reshaping of social mores and economic opportunities, carried out over a number of years, in the teeth of determined ideological opposition’…

bianca steele 09.03.09 at 2:48 pm

How amusing — when my comment gets out of moderation, it will appear that John Protevi’s mention of “millstone” will be a reference to Margaret Drabble’s novel of that name, after my previous mention of her sister.

Salient 09.03.09 at 3:16 pm

PS: maybe even better: so-shall-(s)he-zoom, ‘cause we want equality of zoom, don’t we?

Yeah, I was thinking that. Also cool: the change of gender, when back-translated, gives us socialschism. Commence jokes, please.

John Protevi 09.03.09 at 3:22 pm

bianca steele @ 82: I’m always glad to help make CT a more intertextual site, and now it seems some time-space continuum wormhole thingie is doing that for me even without my knowledge!

Yarrow 09.05.09 at 2:43 am

Socialism doesn’t work because nobody likes to clean toilets. (I can’t persuade myself to agree with Ursula Le Guin that “making order where people live†is sufficiently satisfying when that means cleaning their toilets.)

That’s what the tenth-day rotationals are for on Anarres, no? Every tenth day you do a different job from your usual. I do know some folks who do cleaning as a sort of ten-day rotational job and enjoy it (not necessarily toilets in particular, but even fun jobs have parts that are less fun that you nevertheless do to get the job done).

Comments on this entry are closed.