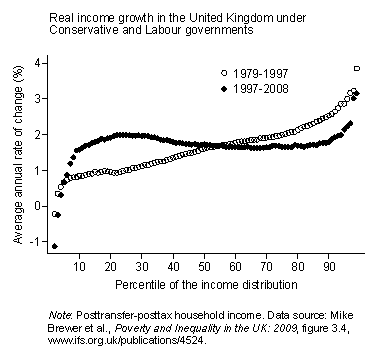

“Matt Yglesias”:http://yglesias.thinkprogress.org/2010/09/new-labour-and-inequality/ and “Brad DeLong”:http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2010/09/in-which-matthew-yglesias-observes-that-innumeracy-is-an-awful-thing.html have argued that this graph, from “Lane Kenworthy”:http://lanekenworthy.net/2009/06/01/did-blair-and-brown-fail-on-inequality/, shows that we shouldn’t be too critical of Labour’s performance with respect to inequality over their 12 years of government in Britain.

“Matt Yglesias”:http://yglesias.thinkprogress.org/2010/09/new-labour-and-inequality/ and “Brad DeLong”:http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2010/09/in-which-matthew-yglesias-observes-that-innumeracy-is-an-awful-thing.html have argued that this graph, from “Lane Kenworthy”:http://lanekenworthy.net/2009/06/01/did-blair-and-brown-fail-on-inequality/, shows that we shouldn’t be too critical of Labour’s performance with respect to inequality over their 12 years of government in Britain.

Both Matt and Brad are pushing back against “Chris’s post below”:https://crookedtimber.org/2010/09/30/its-about-the-distribution-stupid/, which argued that Labour had done very little about equality. (Although in his remark on my comment on his post, Brad now seems to suggest that his post was a pre-emptive strike against what Chris would go on to write in comments.) There’s a natural rejoinder on behalf of Chris, which has been well made in both Matt and Brad’s comments threads. Namely, if the graph really showed that things had gotten better, equality-wise, the Gini coefficient for the UK would have fallen. But in fact it rose, somewhat significantly, over Labour’s term. Indeed, the “IFS Report”:http://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/4524 that the graph is based on shows quite clearly that it rose markedly towards the end of Labour’s term.

So I got to thinking about how good a measure “Gini coefficients”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gini_coefficient are of equality. I think the upshot of what I’ll say below is that Chris’s point is right – if things were really going well, you’d expect Gini coefficients to fall. But it’s messy, particularly because Gini’s are much more sensitive to changes at the top than the bottom.

Because my own thoughts on this are such a mess, I thought I’d hand over to two other characters to handle the back-and-forth.

ACHILLES: Imagine you’ve got a reasonably unequal society.

TORTOISE: You mean 1997 UK, don’t you?

ACHILLES: I do, but any will do.

TORTOISE: I’ll imagine 16th Century Venice then. I like canals.

ACHILLES: Suit yourself. Now imagine that this society gets 30% richer over a period of a few years.

TORTOISE: Yay! More canals!

ACHILLES: And this 30% increase in real income is distributed in proportion to how much income people had at the beginning of the example. In other words, since it was a very unequal society to start with, the gains are distributed very unevenly. So the society has gotten worse with respect to equality.

TORTOISE: Wait a minute. In this example the ratios between incomes of people in the society doesn’t change as a result of the increase. So the Gini coefficient, which is only sensitive to ratios of incomes, doesn’t change. And since the Gini coefficient is the perfect measure of equality, the society hasn’t gotten worse with respect to equality; rather, it hasn’t changed a bit.

ACHILLES: But now the society has all the inequality embedded in the initial position, plus the inequality embedded in the distribution of the new wealth. That’s worse than what they started with.

TORTOISE: Do you have a better measure of inequality than Gini?

ACHILLES: No, but one can be sceptical that a model is universally applicable without having a better model to put in its place.

TORTOISE: Seems like lazy talk to me. In any case, that’s not what actually happened in the UK, 1997-2009. (Which I know is what this is really all about for you.) That there graph slopes downward in the middle section. It isn’t flat, like in you’re example.

ACHILLES: Only if you ignore the tails. I agree though that if you ignore the tails it slopes down. That’s in large part an effect of how the y-axis is drawn. If it was drawn in pounds (or real purchasing power) it would slope up, not down. Eyeballing the graph, it looks like most people got a 1.5% per year real income rise (on average) plus something like a £2 per week per year raise. In other words, it was something like 3/4 due to the gains being distributed in proportion to starting income, and 1/4 due to everyone getting one shiny coin per week extra each year.

TORTOISE: Why are we eyeballing this? Don’t you have the numbers?

ACHILLES: Actually, no I don’t. The IFS study includes a graph, but not the table it is based on.

TORTOISE: I’m thinking I’m going to lose my standing as the lazy one in this dialogue at this rate. In any case, wouldn’t that mean Gini went down. And as we went over earlier, Gini is perfect. So Labour wins, Bertram loses, nyah nyah nyah nyah.

ACHILLES: But Gini didn’t go down, it went up. (And I’m not conceding that it’s the perfect measure.)

TORTOISE: Ah yes, I imagine that had something to do with those tails at either end of the graph. It’s probably something to do with those. You know, when there is a large increase in in-kind payments to the very poor, weird things happen at the lower tail. That’s probably all there is to it.

ACHILLES: That’s probably not all there is to it. Although I am too lazy to find the real numbers and confirm this. But I do have a nice toy model to suggest it.

TORTOISE: Ooh, a toy model. Are you a philosopher or something?

ACHILLES: Something like that. Let’s say we have a society with 100 people, n1, through n100, and let’s say the income of each person ni is i. Surprisingly, this only leads to a Gini of 0.33, which is lower than most existing societies. It does feel fairly unequal though.

TORTOISE: Only 0.33, not too bad, not too bad.

ACHILLES: Now let’s imagine we reduce the income of the bottom 9 people by 100%, i.e., to 0. This raises the Gini obviously, but not by that much. It only goes up to 0.3409. (At least if Wikipedia is right that “this equation”:http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/b/b/5/bb50601acc135c45a24bb0493f7555b4.png works.)

TORTOISE: A Wikipedia equation. Nice, very nice.

ACHILLES: Yes well, you get what you pay for here. Anyway, let’s restore the income to those 9 people, which is pleasing to do, and now double the income of the top nine earners in the society. Now the Gini rockets up to a more real-world like 0.4149. So Gini is much more sensitive to rises at the top end than falls at the bottom end, at least if this toy model is anything to go by.

TORTOISE: I’ll finally admit, this seems like a weakness in the Gini model. After all, when we care about equality, we should care more about what goes on at the lower end than the upper. But it also suggests to me that the rise in Gini under Labour is an artifact of a model that’s too sensitive to the top, combined with a very pleasing rise in the incomes of my City friends.

ACHILLES: So the model is perfect, except when it grounds complaints about Labour and the City, in which cases it should be set aside.

TORTOISE: You may very well think that. I couldn’t possibly comment.

I come out of that liking Achilles’ position more than Tortoise’s, though I also like the conclusion they draw at the end. In principle a rise in Gini that was caused solely by the very rich getting even richer could be accompanied with an intuitive improvement in equality, if we saw in general things getting better for the poorer across the board. But that’s really not what we saw in Britain. And in a period of economic growth, you’d expect Gini to fall even if we were standing still on equality. When it rises, we have an indication that things are getting considerably worse, and I don’t see anything in the data to defeat that indication.

{ 77 comments }

Lemuel Pitkin 10.01.10 at 3:36 pm

when we care about equality, we should care more about what goes on at the lower end than the upper.

I think this claim could use some elaboration.

dsquared 10.01.10 at 3:39 pm

For people who don’t want to take Brian’s calculation on trust, an even simpler numerical example. You have $5 and I have $500. If the government comes along and gives you $10 and me $900, then inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient (and nearly any other summary statistic you care to name) will have fallen.

Brian 10.01.10 at 4:08 pm

Lemuel Pitkin said,

I think this claim could use some elaboration.

Fair enough. I was intuitively thinking about the following two kinds of cases.

* 80% of the population is comfortably well-off, and 20% of the population is in grinding poverty.

* 90% of the population is moderately well-off, and 10% of the population is living the high life.

I think the second society is better. Not perfect, but better. Now many might disagree, and I certainly don’t have good reason for thinking I’m right here – just something like a gut instinct.

If my instincts are right, there are still two ways to explain it. One, it could be that equality matters, and poverty matters. The two societies are roughly equal on equality terms – I think they’d have roughly equal Ginis. But the first society features a lot of poverty, and poverty is bad in a way independent of equality considerations. But I’m sceptical of attempts to ‘factor out’ badness in this way. I don’t think we can make a lot of sense of the badness of (avoidable) poverty independent of the badness of inequality. And that’s what really drives the comment Lemuel thought needed elaboration.

In slightly shorter terms, when the income graph shoots up at the top end, that’s (ceteris paribus) bad because it means that some people are arbitrarily benefiting at the expense of others. But when the graph shoots down at the lower end, that’s still happening, and the result is that some people are literally impoverished. That, I tentatively think, is worse.

Brian 10.01.10 at 4:11 pm

If you trust neither me nor dsquared, here is the Excel sheet I used to do the Gini calculations.

https://crookedtimber.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/GiniCT.xls.

mpowell 10.01.10 at 4:16 pm

A couple of comments:

1) Regardless of whether your think things got marginally better or worse under Labor, it is still the case that whatever inequalities developed under the Tories just got baked into the system. So we certainly shouldn’t be congratulating anyone for that.

2) I think a system that does well for the 10-40 percentile group while the <10 group stays flat isn't that bad. I know that Rawls may not agree, but this is what keeping a safety net together while improving opportunities for the working poor and lower middle class would look like. Though it would be nice to know what is the problem with those last 2 percent.

3) I would agree that rapidly rising incomes at the top should not ideally get the weighting that they do under gini, but due to power effects it tends to develop into a positive feedback loop and everyone else getting screwed. So realistically rapidly rising top percentile incomes is a major problem.

Lemuel Pitkin 10.01.10 at 4:35 pm

Brian,

I think your intuition is right, as far as it goes. But it’s only part of the picture. One reason we are concerned with inequality is the deprivation (both absolute and relative) of those at the bottom. But another reason is because we believe that autonomy and flourishing require collective self-government, democracy in the broad sense of an active role in the decisions of the community. And here the big problems are created by the top end of the distribution, not the bottom.

Do you know Christopher Boehm’s Hierarchy in the Forest? It’s a very compelling (IMO anyway) look at the antrhopological basis of egalitarianism, and the key point it makes is that where we find — as we often do — equality, democracy and freedom in simple societies, it’s because of concerted, self-conscious measures to prevent any individual from rising to a position of dominance.

Chris Bertram 10.01.10 at 4:41 pm

Many thanks for this post Brian.

Let me just say something which I tried (but clearly failed) to communicate in comments over at DeLong’s site. There weren’t any numbers in my post. My claim was, rather that New Labour had abandoned Labour’s traditional goals with respect to distribution in favour of other goals. That claim may or may not be correct, and Marc Mulholland disagreed in comments at CT, but its truth or falsity does not depend on the actual evolution of the income distribution from 1997 to 2008 (or 2010). This is for the very simple reason that a government which abandoned a distributive goal and pursued a different objective (say growth) would still be pursuing a policy with distributive _effects_ , effects that might increase or decrease relative income inequality.

However I do also believe that Labour’s “intensely relaxed” attitude to inequality led to worse results, from an egalitarian perspective, than could have been achieved by a more determinedly egalitarian government and that this had the further consequence of damaging the well-being of the least advantaged (since I believe that well-being to be sensitive to the amount of inequality). That is why I welcomed Ed Miliband’s shift away from Blarism when he spoke of equality and social justice.

(Just a further brief comment on Brian’s hypothetical two societies: of course, at a _fundamental_ level we shouldn’t care about the distribution of _income_ because income merely has instrumental value. In fact, at the fundamental level, the right answer might not be egalitarianism at all, but prioritianism or some mixed view perhaps. Prioritarianism, say, would support the judgement that the second society is better. But a fundamental commitment to prioriarianism with respect to well-being can support a _policy_ of pursuing greater equality with respect to income, and normally I think it does.)

Lemuel Pitkin 10.01.10 at 4:49 pm

at a fundamental level we shouldn’t care about the distribution of income because income merely has instrumental value. In fact, at the fundamental level, the right answer might not be egalitarianism at all, but prioritianism

Again, I think this is only part of the story. It implies that our judgment of a society simply consists of adding up (by some metric) the individual situations of the people in it. But there are some aspects of a society that are irreducibly social, and insofar as income means power, it’s part of those. Another way of saying this is that the value of being a full participant in collective decisions, is not just your interest in those decisions producing an outcome that makes you happy.

Lemuel Pitkin 10.01.10 at 5:04 pm

There’s also the relative-deprivation point that Brad DeLong made so eloquently here. Consumption at the top is nearly all positional goods. So adding income at the top doesn’t just improve social welfare less than adding income lower down the distribution; it may actually reduce it.

Between the power and positional-good factors, it seems plausible to me that if you, say, took $30 billion away from Carlos Slim and didn’t change the income or wealth of anyone else in Mexico, most Mexicans would end up better off.

Brian 10.01.10 at 5:06 pm

Lemuel and mpowell’s comments have made me think I was being a little myopic in my original judgments. Here’s a more nuanced position.

* In static terms, inequality at the bottom is worse than inequality at the top. That’s because it features not just inequality, but impoverishment.

* In dynamic terms, inequality at the top has a nasty feature that inequality at the bottom doesn’t have. And that’s that it strongly threatens to undermine democracy, and more generally political equality. And it does so in a distinctive way since the rich can hoard power as well as wealth. Once that happens, you’re in a cycle you’re likely to get stuck in for a long time, and arguably not a cycle you can ‘reform’ your way out of. So this kind of inequality means not just inequality today, but tomorrow and forever more.

I think in the post, especially the last paragraph, I wasn’t thinking dynamically enough, and should read books like Boehm’s to correct this.

engels 10.01.10 at 5:23 pm

New Labour had abandoned Labour’s traditional goals with respect to distribution in favour of other goals

You’re entitled to make your own judgments of what Blair was doing and thinking but I think it’s important that this is not at all how Blair represented himself and New Labour. Rather, what I think he always said was that Labour’s goals should not change but new means were required to pursue them. This quote from a joint statement by Blair and Schroder on The Third Way is representative:

mds 10.01.10 at 6:08 pm

“By which we mean, our governments will no longer have any time for them.”

mpowell 10.01.10 at 6:51 pm

@10: Yeah, that is a good correction. I do wonder, though, if there is an absolute level of top end inequality where this becomes an issue and below which there is a largish region where it is not too much of a problem. This would probably be a function of a lot of other factors, including the legal status of campaign funding. But I think the rates of change could be less important than the absolute level if you want to practically speaking ask whether they are too high in some society or another (although maybe a fast increasing rate is a good indicator that you do have a problem!)

Lemuel Pitkin 10.01.10 at 6:57 pm

10 seems right to me.

engels 10.01.10 at 7:43 pm

I found #10 puzzling.

There’s no reason why ‘inequality at the bottom’ would necessarily be correlated with poverty. Equally, there’s no reason why ‘inequality at the top’ wouldn’t be. For the first, consider a society which is substantially unequal but where everybody is comfortably above the poverty line. For the second, one where the majority lives just below the poverty line and a small group lives far above it.

It also doesn’t seem obvious why the existence of a concentration of wealth ‘at the top’ is thought to seriously damage democracy or political equality whereas the existence of excluded, effectively disenfranchised people ‘at the bottom’ is not.

Maybe these were not meant as general claims but then I’d like to know the conditions that are supposed to apply.

Lemuel Pitkin 10.01.10 at 7:56 pm

There’s no reason why ‘inequality at the bottom’ would necessarily be correlated with poverty. Equally, there’s no reason why ‘inequality at the top’ wouldn’t be. For the first, consider a society which is substantially unequal but where everybody is comfortably above the poverty line. For the second, one where the majority lives just below the poverty line and a small group lives far above it.

We’re discussing the contemporary UK and, by extension, other advanced capitalist countries. Not income distribution in society in the abstract, about which (as I’d think you’d agree) not much useful can be said.

It also doesn’t seem obvious why the existence of a concentration of wealth ‘at the top’ is thought to seriously damage democracy or political equality whereas the existence of excluded, effectively disenfranchised people ‘at the bottom’ is not.

Disenfranchised people at the bottom are excluded, but their exclusion doesn’t have any strong tendency to grow over time, nor does it preclude robust democracy among the rest of the population. (Of course it’s still bad!) There are plenty of historic examples you could point to — indeed, just about any historic example you could point to of egalitarianism and freedom includes some excluded groups. A very powerful group at the top, on the other hand, has the ability to use its existing power to accumulate more, so that kind of inequality tends to snowball.

Of course you can make all sorts of arguments at the level of pure abstraction, if you want. But I think the evidence from concrete societies is pretty dispositive on this point.

Chris Bertram 10.01.10 at 8:21 pm

engels @11. I’ll refer you to my reply to Marc Mulholland in the earlier thread. Though I think there’s room for reasonable disagreement here, I find it hard to believe that Blair, Mandelson, Byers and Milburn really gave a damn about equality.

Omega Centauri 10.01.10 at 8:55 pm

Brian pretty good discussion. I think I am largely in agreement about inequality at the bottom, i.e. that the number below some “poverty level” is important. This presumes that below some level of income, important nonpositional goods must be forgone, but above this magic level, the marginal dollar is enturely spend on position rather than needs based goods.

Your dynamicical theory is important to the extent that a society allows money to buy power. For instance in the US, where politicians and political party live or die on donar contributions of money, and advertising/propaganda, then the wealthy are very much more politically influential. I’m not at all clear how it works in the UK, are campaigns funded by the government, as opposed to private economy? If you disallow the conection between wealth and political influence then the dynamical situation should change. Also in this country, the very rich can fund institutions whose purpose is to propagate whatever ideology the rich donors want flogged. Some constraints on such activity might go a long way towards addressing the dynamical issue.

Salient 10.01.10 at 8:58 pm

Though I think there’s room for reasonable disagreement here, I find it hard to believe that Blair, Mandelson, Byers and Milburn really gave a damn about equality.

You might have an even stronger case than this. If they did give a damn about inequality, then presumably, they should have (and should have expressed) feelings of remorse/regret/failure regarding their inability to fulfill those aspirations. Or at the very least, they should have spent a good deal of time spinning the results they achieved as evidence they made progress on those aspirations, or some such thing: it should be prominent in what they say in their reflections and memoirs. I’m tempted to go skim Blair’s A Journey to see if he says anything about this, but it’s probably better for my mental health if I just posit that he doesn’t and leave it to someone else to go verify it.

ph 10.01.10 at 9:22 pm

the “toy example” doesn’t make much sense. given the hypothetical gini of .33, the income subtracted in the first case is not nearly as much as the income added in the second example.

suppose the bottom decile has an average income of 10 and as a group they receive 4% of the total income; and that the upper decile has an average income of 60 and as a group they receive 22% of the total income. when you deprive the bottom 10 of all their income, you’re removing $100; when you double the income of the richest 10, you’re adding $600. it makes perfect sense that the Gini coefficient is higher in the second case.

the real test is: what happens when the marginal changes are equal?

suppose a population comprised of 10 people with the following incomes: 10 11 12 15 16 20 30 31 50 55. The Gini coefficient for that is – surprise, surprise – 0.333.

now let’s subtract $5 from the poorest person. the Gini coef is now .356, a 7% increase.

on the other hand, if instead we generously donate $5 to the richest one, then the Gini coef grows to just .345 (+ 3.3% .

so is the gini coef more sensitive to the tail of the distribution? well, no. it is more responsive to transfers involving people closer to the median of the distribution.

heedless 10.01.10 at 9:26 pm

This is a seductive line of reasoning, but the historical evidence doesn’t bear it out.

First, there is the obvious point that of the top .1% of Americans (the ones who really drive up the Gini coefficient), very few of them were born with that kind of money. Most of them came from the upper-middle class, but they made the jump from the 80th percentile to the 99th by surpassing the previous generation’s top .1%, not by inheriting from them. Precisely because there is so much turnover, there is none of the solidarity necessary to wield power as a group.

Second, the most powerful factions tend to be professional, ideological, or tribal, and tend to come from the middle and upper middle classes. In the US, that would be the farm lobby, the teachers’ union, the AMA, the UAW, the Chamber of Commerce, the Christian Right, and the banking lobby. (Bankers are quite rich, but they seem to influence policy more with the traditional “everyone who is an expert on my industry is in my industry” model of regulatory capture than with disproportional campaign spending.) In less stable nations (or even in pre-civil rights US), you have to worry about racially or tribally motivated disenfranchisement, but again, those are middle class movements targeting the very rich, the very poor, or the very different.

engels 10.01.10 at 9:28 pm

I don’t personally feel that discussing the meaning concepts like equality in the abstract is pointless.

To be clear, Brian’s claims about inequality are meant to apply only to advanced capitalist countries? I think you can have an advanced capitalist country with low poverty and significant inequality ‘at the bottom’ though.

I don’t know why you think political exclusion or subordination of an out-group has no tendency to reinforce itself over time whereas political domination by an in-group does.

piglet 10.01.10 at 10:43 pm

If the figure above were a flat line, i. e. each income group had the same relative gain, the Gini would stay exactly constant. You’d need a downward sloping curve to reduce Gini. Even though the line for 1997-2008 slopes downward in the middle part, that is probably more than offset by the uptick upwards of 90%. Gini is more sensitive to the top because the relative increase at the top is more consequential in absolute terms. To reduce Gini you need to prevent the rich from getting richer period.

Peter Whiteford 10.02.10 at 1:06 am

An apology if this comes over as an intemperate rant.

First the Gini coefficient is well known to be more sensitive to changes in the middle of the distribution and not to changes at the extremes.

For those who have not read some of the earlier discussion on this at Brad DeLong’s place, I pointed out that in the economic literature on inequality “scale independence” is generally agreed to be one of the fundamental qualities that any measure of inequality should satisfy. Now when I say generally agreed, I should have been more precise – if you used a measure that was not scale independent it wouldn’t be published.

For example, if everybody’s income doubled would inequality increase? If everybody’s income halved would inequality decrease? (If you answer yes to these questions, then you are in danger of verifying the opinions of those who see egalitarians as happy to shrink the pie.)

Put another way, compare two countries – in one the poorest person has an income of $1 and the richest person has an income of $100,000 and in the other the poorest person has an income of $10,000 and the richest person has an income of $110,000. If we compare the absolute income levels then country A has a narrower dispersion – $1 less than $100,000, but in relative terms country B is much less unequal.

If you don’t have scale independence, then virtually by definition poorer countries will be seen as more equal than richer countries. In fact, if you don’t have scale independence then international comparisons and comparisons over time basically become meaningless.

Over at Brad DeLong d squared says: “I think scale independence is a desirable property in some cases but not others. If I have $1 and you have $1m, and the government gives me $500,000 and you $600,000, then scale-independent measures are going to give the right answer even though the absolute size of the gap has increase. On the other hand, if I have $1 and you have $1m, and the government gives me $2 and you $1.5m, then a scale-independent measure is surely giving the wrong answer when it says that 0.00012% > 0.0001% and that therefore things have got more equal.â€

Well, the response to this is where does the government get this money from? You have created two examples in which the transfers somehow exceed the size of the total pot of money. In any real world country transfers get paid by taxes, so either you have a third person or group whom you have to include in the calculation, or the money comes from the richer group, in which case it is pretty obvious that inequality has been reduced.

ckc (not kc) 10.02.10 at 1:39 am

First, there is the obvious point that of the top .1% of Americans (the ones who really drive up the Gini coefficient), very few of them were born with that kind of money. Most of them came from the upper-middle class, but they made the jump from the 80th percentile to the 99th by surpassing the previous generation’s top .1%, not by inheriting from them. Precisely because there is so much turnover, there is none of the solidarity necessary to wield power as a group.

data?

F 10.02.10 at 2:51 am

It is almost impossible to believe that scale independence didn’t get mentioned until now, given the arbitrariness of the unit of purchase.

On the other hand, it also difficult to believe that poverty lines haven’t been mentioned much.

F 10.02.10 at 2:55 am

To say more exactly what I mean, all of the hypotheticals about increases in high-end incomes involve massive increases in the money supply. If you are a monetarist, this means massive inflation, to the extent that, by definition, inequality increases. Of course, the real world is more complicated, but at the extremely simplistic level of these thought experiments, wouldn’t that be important?

ckc (not kc) 10.02.10 at 2:56 am

PS poverty is real only if it is scale independent (obscene wealth is, of course, unreal)

sg 10.02.10 at 3:28 am

You can judge inequality another way, by looking at inequality in all the markers of people’s lived experience: education, health, regular consumption of healthy food, nuisance crime, accidents, etc. The Labour government commissioned an inquiry into this (the Marmot Review), and it showed categorically that inequality has either not improved or has gone backward on all of these measures.

And some of those measures are truly stunning – the level of non-approved absenteeism from school in the poorest 20% of society is astounding, as is the relative rate of minor fires in the areas where poor people live.

So even if income inequality has improved a little, the real lives of the poor haven’t.

Doing the classic internet thing of not reading intervening comments, so sorry if anyone already said this.

Chris Brooke 10.02.10 at 7:05 am

I find it hard to believe that Blair, Mandelson, Byers and Milburn really gave a damn about equality…

There’s not much on equality in Blair’s memoir, to be sure. He does say this, however, in a discussion of education policy (p. 578):

*** For me, this was the point. However well motivated, it [Gordon Brown’s objection to ‘academies’] was classic levelling down. It was an argument that went to the heart of what New Labour was about and its championing of aspiration. Equity could not and should never be at the expense of excellence… ***

Tim Worstall 10.02.10 at 9:06 am

@ 25. Piketty & Saetz (if I’ve spelt that right). One of the points they make about the return to 1920’s levels of income inequality is that 1920’s levels were driven by returns to capital (physical or financial) while 2000’s inequality is driven by returns to labour (which we could classify as returns to human capital, rent seeking, skill, whatever we like really). Given that P&S, at least in the US (there is I think a UK study which one of them has done) are the providers of the basic data that everyone’s discussing seems fair to take the other points they make as well.

“Just a further brief comment on Brian’s hypothetical two societies: of course, at a fundamental level we shouldn’t care about the distribution of income because income merely has instrumental value.”

Quite possibly true which is why people like Tyler keep insisting we should look at consumption inequality, not income.

“Consumption at the top is nearly all positional goods.”

Also quite possibly true. Which leads to the implication that the inflation rates faced by the two groups are different. More money going to those who are fighting over positional goods is going to increase the cost of those positional goods: at least, one would assume that it would do so more than the non-positional goods which everyone else is spending their (however gently rising) incomes upon.

Consumption inequality could therefore be less than income inequality…..and if it’s consumption inequality that we should be concerned about….

dsquared 10.02.10 at 12:10 pm

You have created two examples in which the transfers somehow exceed the size of the total pot of money.

I had actually more or less picked the numbers to be right within an order of magnitude with respect to the top and bottom .1% of the global income distribution twenty years ago and now. This is Brian’s point also, and you are right that it does open up the charge of being willing to shrink the pie in order to get a more equal distribution (although so would any social utility function that’s decreasing in wealth, which makes it even more puzzling that scale independence is considered sine qua non). But your measures are open to precisely Brian’s point – that they can start from a massively unequal distribution, distribute gains from progress in a massively unequal fashion and get more equal.

oliver 10.02.10 at 9:35 pm

One statistic that caught my eye in that IFS report is that real incomes of the poorest decile grew at 0.8% from 1979 to 1997 vs. 2.5% for the top decile, and at 1.6% for the bottom vs. 1.8% for the top decile from 1997 to 2010.

I think that “income inequality continued to worsen under Labour, but at a significantly slower rate than under the Tories” is actually not an achievement to be sneezed at.

Peter Whiteford 10.02.10 at 9:54 pm

d squared

No. You don’t calculate the Gini from the top and the bottom incomes only but from the entire distribution, and in the example you have now given us more details of you need to account for where the money comes from. A transfer from the middle to the richest would increase inequality measured by the Gini, so your objection doesn’t hold.

JG 10.02.10 at 10:21 pm

you need to account for where the money comes from.

Sorry if I’m way off here, but isn’t the answer absolutely obvious? Economic growth. Gains from progress. Again, really sorry if I’m being an idiot here, but the example which kick-started this whole discussion was how the gains from progress over the last 30 years have been distributed (always incredibly unequally, despite relatively equal income growth in recent history) . Talking about it in terms of the government giving the rich x and the poor y is a funny way of talking about it, but not uncommon.

Peter Whiteford 10.02.10 at 11:33 pm

When d squared said that the government gave a transfer I took him at his precise word – that is the government did it, not the market. This raises the important issue of what the government does and what the various markets do, and how they influence each other.

I’m not asserting authority here but I am the person who wrote the chapter in the OECD report “Growing Unequal†(2008) that discusses how government tax and transfer policies affect the distribution of income, so I tend to interpret these words precisely.

It is important to understand the limitations of these sorts of studies and the statistics on which they are based. What governments get measured as doing in household surveys is taking taxes away from people and giving transfers to people.

Law don’t show up directly – for example, when the UK Labour government introduced the minimum wage this does not show up as government doing anything in most income distribution studies, but as a change in market distribution. Also to the extent that government policies encouraged speculation and boom (and then collapse) this also will not show up as government activity, but purely as the operation of the market.

It certainly seem plausible to me that government policies in lots of countries contributed to the boom in high incomes over the past 30 years, but I doubt that the entire increase in market disparities can be attributed to government policy, unless you take the view that government is responsible for absolutely everything that happens in their period of office.

mpowell 10.03.10 at 2:48 am

@36: This comment is kind of revealing. I think most of the people on this forum are coming from the perspective where the government is responsible for the economic structure which gives rise to various income distributions. I can imagine why any given study might attempt to separate these issues, but from a big picture perspective it seems silly to ignore the government’s influence on the market- after all the market only exists because of government policy! Really if you assume a priori that the government influences income distribution more through tax policy than industrial policy, you are begging the question.

Peter Whiteford 10.03.10 at 3:59 am

You would need a completely different form of analysis. What income distribution surveys contain are statistics on the incomes of private households, which are not really the basis for evaluating industrial policy, for example. Household surveys contain outcomes that are clearly influenced by explicit and implicit policies, but in policy terms they only contain information on direct tax and transfer policies.

I think the point here is thatone needs to be careful in taking one form of study – such as that of the IFS cited above, and using it to draw conclusions about issues which it really can’t tell us about.

Jim Rose 10.03.10 at 7:55 am

Peter Whiteford,

thanks of the interesting posts

should not discussions of inequality at least be based in terms of consumption rather than income?

John Rawls oppose progressive income taxes and preferred progressive consumption taxes because it “imposes a levy according to how much a person takes out of the common store of goods and not according to how much he contributesâ€. A simple way to have a progressive consumption tax is to exempt all savings from taxation.

Should the inequality measure be current consumption or lifetime consumption?

I did not consume much at university, or did I – there were no tuition fees. There were housing subsidies and free public health care and hospitals because I was on a low income! It was a long time catching up to those high school friends who did not go on to university. They had cars and started to pay-off houses. I did not even have a cheap car until what almost a decade later. Is all this capitalist oppression and inequality?

Guido Nius 10.03.10 at 9:38 am

May I nominate Brian for both the best post and best comment (#10) on CT in 2010?

derek 10.03.10 at 11:30 am

The fact that the application of the Matthew Effect (“To those who have, more will be given, and they will have an abundance”) leaves the Gini coefficient unchanged is a defect of the Gini coefficient (though it’s still better than less naive measures of well-being like GDP per head) . It means the measure itself is “intensely relaxed” about the rich getting relatively richer when the GDP per head grows, as if this was not also an inequality.

Someone above concluded it seemed plausible that if you took $30 billion away from Carlos Slim and didn’t change the income or wealth of anyone else in Mexico, most Mexicans would end up better off. That is almost certainly true (ignoring for a moment the world outside Mexico), because Slim would have to dig relatively deeper into his pockets to employ the labor of one other Mexican, and “employ the labor of” is just another way of saying “tell where to go and what to do”.

Peter Whiteford 10.03.10 at 12:26 pm

“The fact that the application of the Matthew Effect (“To those who have, more will be given, and they will have an abundanceâ€) leaves the Gini coefficient unchanged …”

Your premise is incorrect. The examples given refer to the ratio of incomes between the top and the bottom. This ratio is not the Gini coefficient.

The Gini coefficient does have limitations. This however is not one of them.

Matt McIrvin 10.03.10 at 1:05 pm

So the conclusion is that they were significantly better than the Tories, but not really making the inequality situation a lot better. This sounds familiar from American politics.

Peter Whiteford 10.03.10 at 1:25 pm

Matt McIrvin

I think you have about summed it up.

However the tax credits introduced in the UK are much more redistributive than the EITC in the U SA- although not necessarily a good idea.

Robert Waldmann 10.04.10 at 12:23 am

I am glad that, unlike Chris Bertram himself (above) you are willing to let Crooked Timber readers see the evidence. Odd that he didn’t comment on it or link to your post. People do read blogs from the top sometimes. It’s almost as if Chris Bertram thinks evidence is irrelevant.

Robert Waldmann 10.04.10 at 12:33 am

Now on how to measure inequality ahhh what a long tiresome debate that was. I think the best effort was Atkinson’s who said. First be a utilitarian. Second choose a utility function. Now you can compute the equal income which would give the same average utility. The ratio of actual income to that income is an index of inequality (going from 1 to infinity). This makes us care about the percent growth of income of the very rich. Even if we don’t mind that they are super rich, we do mind that they have so much money — and therefore that people who could use it don’t have it. I’d say the graph used by Yglesias misses that important point (just as you argue).

I’d guess that Yglesias didn’t know about the Ginis. I was surprised by his graph as it didn’t correspond to my sense of what happened which is based on ginis and the share of the richest 1%. I think that what he was looking at was growth under new labour vs growth under the tories. Now better than Thatcher and Major might not be good enough, but things were much better for the lower half.

Chris Bertram 10.04.10 at 9:01 am

Robert Waldmann @45 – since I did, in fact, comment on this post at #7 above, as well as commenting on DeLong’s post, your claim is mistaken. As to “the evidence” – well it is evidence that is relevant to a claim other than the one I actually made, which was about New Labour’s normative commitments.

dsquared 10.04.10 at 2:49 pm

The examples given refer to the ratio of incomes between the top and the bottom. This ratio is not the Gini coefficient

But the Gini coefficient (and the Theil index, and nearly every other scale-independent index) would have shown an improvement in that hypothetical economy.

Tim Wilkinson 10.04.10 at 3:49 pm

After some deeply amateurish fiddling about, I discovered that the Gini ‘coefficient’ (don’t understand why it’s called that – I thought ‘coefficient’ basically meant ‘number handed to you on a slip of paper’), is actually equivalent to mean deviation from the mean, i.e. you get the mean income, then calculate the absolute values of the difference between that and each data value, then divide the mean deviation, so calculated, by the mean income (and divide by 2 to normalise it to {0,1} rather than the {0,2} that taking absolute values gets you).

In other words, you get mean (†or total*) deviation from mean (*or total†) income and relativise it to mean income. This way of calculating it (or looking at it) makes the whole thing much more inuitively comprehensible to non-mathmos (or to me anyway) than the formula used in the OP, which seems to involve tilting the distribution to see how close it gets to a 45° straight line, and in the process generating intermediate values that don’t relate to anything real.

The fact that this can be done – and that there’s nothing terribly black-boxy or sui generis about Gini – also presumably means that the properties of the Gini measure are well-understood by statisticians, and can be compared to those of, say, standard deviation adjusted to be scale independent, por whatever, though here I’m rapidly failing to know what I’m talking about…

Attempting to punch still further above my mathematical weight, I’d guess you could change (1) the baseline for calculating deviation; (2) the divisor used to gain scale-independence, to get different measures which might be more sensitive to, say, the low end of the distribution. Gini uses mean income for both of these: I guess you might want to use the same quantity for both, for reasons that my non-mathematically-trained brain only dimly apprehends. I also suppose that if you used, say, median income or something, you would not necessarily get a measure that is neatly normalised to the unit interval. But that is not a problem, I shouldn’t have thought, and indeed might be quite handy, since squashing an open-ended scale into a fixed interval in asymptotic style doesnt necessarily give very readable stats (or stats that can be usefully compared when rounded to a fixed number of decimal places).

Apologies to those with any methematical sophistication, to whom the above must seem pretty grotesque. But it may be vaguely useful for others like me who have never dedicated the time necessary to get a handle on (a) the concepts, (b) the terminology involved in talking proper-like about this kind of stuff…or it may just be entirely incomprehensible. Never mind. Must do a maths course of some sort when I happen to have a few hundred spare hours knocking about.

One other, slightly-but-not-entirely flippant, remark: an ‘order of magnitude’ does just mean a factor of 10, doesn’t it. The way it gets used often seem to hint at some more salient signficance. I think it should be called an order of decimal magnitude, just to be clear.

Peter Whiteford 10.04.10 at 8:07 pm

dsquared at 48

The Gini coefficient is calculated over the whole distribution, not just the two extremes, so you can’t tell what the effect on the Gini coefficient is from changes in two points alone.

Now in the original post “ACHILLES: Yes well, you get what you pay for here. Anyway, let’s restore the income to those 9 people, which is pleasing to do, and now double the income of the top nine earners in the society. Now the Gini rockets up to a more real-world like 0.4149. So Gini is much more sensitive to rises at the top end than falls at the bottom end, at least if this toy model is anything to go by.”

Well the reason why the Gini coefficient appears (but actually isn’t) to be more sensitive to rises at the top is that this involves doing two completely different things. The first example – reducing the nine bottom incomes to zero – takes 45 units of currency out of the system – while the second example – doubling the incomes of the top nine – adds more than 800 units of currency to the top.

Tim Wilkinson 10.04.10 at 10:23 pm

But, just to be clear, it is more sensitive to a percentage change at the top than to an equal percentage change at the bottom. If you want to keep a fixed total, just distribute a compensating sum equally across all other data points.

That’s so long as your changes aren’t so big relative to the total as to cause any weird effects.

The only problem is if you make exactly the same change to top and bottom incomes (say multiply by 1.2), I don’t know how to compare the changes in Gini, since one is an increase and the other a decrease relative to the initial value. But if you compare the effect of multiplying the top by 1.2 to the the effect of dividing the bottom by that value (or presumably better, multiplying it by 0.8) then, again assuming no odd effects, the former change will give you an unambiguously bigger difference.

dsquared 10.04.10 at 10:59 pm

But this is all a bit quibbletastic with respect to Brian’s original (and in my view correct) point that scale independence itself isn’t wholly desirable, because there are plenty of occasions in which a very unequal society sees rapid economic growth which is itself very unequally distributed. If an economy in which 90% of the population are on a dollar a day and 10% are millionaires sees a doubling of everyone’s incomes, then there’s definitely a meaningful sense in which it has become more unequal.

Peter Whiteford 10.05.10 at 12:29 am

Ingvar Kamprad lives in Sweden (Gini coefficient around 0.23) and is the 11th richest person in the world (courtesy of Ikea). There is one person from Argentina (Gini of 0.46) in the Forbes rich list and his wealth is about one-twentieth that of Kamprad’s.

Now the lowest income in Argentina is much lower than the lowest income in Sweden, but you can’t go below zero. So does this mean that Sweden is more unequal than Argentina because the gap between the top and the bottom is wider in money terms? Or Singapore or South Africa – all countries where the richest are much less wealthy than Kamprad?

The richest person in Denmark has wealth that is about three times higher than the richest person in China, so is Denmark more unequal than China?

The problem with the apparently commonsense concern about income gaps is that it leads to inconsistent rankings of countries (and time periods). And rankings that to me at least violate commonsense.

Tim Wilkinson 10.05.10 at 10:07 am

it leads to inconsistent rankings of countries (and time periods). And rankings that to me at least violate commonsense

Isn’t the problem here that it’s actually only the latter? If not, then it should be possible to give a knockdown toy counterexample.

Zamfir 10.05.10 at 10:25 am

Ingvar Kamprad lives in Sweden

Oh no. He lives in Switzerland and has lived there for decades, mainly because he wants to avoid Swedish taxes as much as possible, which he hates with the ferocity of Scrooge McDuck. For the same reasons, his wealth and perhaps the ownership of IKEA are distributed over a shady network of Dutch charity foundations. The end result might well be that he literally can’t touch most of his wealth, which he greatly prefers over paying taxes.

He is, ahem, not a great example to illustrate the Swedish approach to equality.

dsquared 10.05.10 at 12:25 pm

The problem with the apparently commonsense concern about income gaps is that it leads to inconsistent rankings of countries (and time periods). And rankings that to me at least violate commonsense.

The problem with the Gini coefficient is that it can also lead to rankings that violate commonsense. For example, the South of Sudan also has a Gini coefficient of around 0.46, the same as Argentina (south of Sudan has few millionaires, but quite a lot of subsistence farmers). But in this case, the absolute gap is telling you more; South Sudan is a much more unequal society than Argentina.

Zamfir 10.05.10 at 1:21 pm

But dsquared, isn’t that more due a an non-monetary dimension to the unequality? After you have roughly enough money to buy a yacht and a sportscar, more money doesn’t really buy material consumption anymore, but mostly power over other people.

If the current political climate of Argentina does a better job of keeping the power of the rich in check than that of South Sudan, then Argentinian billionaires might well in an essential sense be more equal to ordinary people than Sudanese millionaires.

dsquared 10.05.10 at 1:54 pm

No, I think it is due to the specific problem that Brian identified – South of Sudan started out as a society which would have (correctly) been identified as much less equal than Argentina, and then had a windfall gain (the oil revenues) which was itself extremely unequally distributed. But because the distribution of the gain was somewhat less unequal than the pre-existing state of inequality, it brought the Gini coefficient (and Theil index, and any other scale-independent measure) down.

Zamfir 10.05.10 at 2:31 pm

Just to make sure I am understanding you correctly: you mean that people who used to have million now have (an income of), say, 2 million, while people who used to have a thousand now have more than two thousand?

At first sight, I am pretty OK with calling that an increase in equality. The group of poor people you need to get to a rich person’s income or wealth is now smaller than before. So I am still not entirely seeing your point.

The absolute income gap between me and a surgeon is larger than between me and Sudanese subsistence farmers, but I’d say that I am much more “equal” in income to a surgeon than to a subsistence farmer. If Sudanese farmers got my income, and my Sudanese equivalents got a surgeon’s income, I think most would agree that Sudan got “more equal”, even if absolutely differences would increase.

dsquared 10.05.10 at 3:11 pm

No – as I say, South of Sudan didn’t have many millionaires and still doesn’t. It’s more like the urban middle class went from around 20% to around 30% of UK median income, while the subsistence farmers went from slightly less than a dollar a day to slightly less than two dollars.

Zamfir 10.05.10 at 3:35 pm

This still feels like an increase in equality to me, unless I am missing something.

If prices of necessities for example rose fast too, so that the poor farmers still have the same amount of stuff. Or that given their subsistence status, their market income is only a part of their material income, so a doubling in market income is not really a doubling in material stuff. Or their increase in income just meant less free stuff from aid agencies or the government.

But if you mean that their material income in any shape doubled, while that for richer urban dwellers only rose by 50%, I don’t see the problem with calling this a reduction of inequality.

dsquared 10.05.10 at 3:44 pm

I guess we just find different things intuitive then – I would look at it and say that they’re still subsistence farmers, while the urban population (actually only some of them of course) have 50% more consumer goods. You’ve got one population that’s on its way to a middle-income lifestyle, and another that’s still stuck in a development trap; this society’s getting more unequal.

Zamfir 10.05.10 at 3:44 pm

Just to be clear- I am not arguing a case here. I suppose you know much more about the Sudan than I do, and I am just not fully understanding your point here.

Tim Wilkinson 10.05.10 at 3:49 pm

This whole approach sounds wrong to me – if inequality is concentration of wealth, I think there’s a precise (enough) analogy with concentration of a salt solution (say). If you add a less concentrated solution, the result will be less concentrated than the original one, but more so than the stuff you added. I think (but this is still at the level of ‘common-sense’ intuition) that’s just how equality – is distinct from all the other things we might be interested in – works.

If the problem is that the gains should be distributed more equally than they are, or even in such a way as to compensate entirely for preexisting inequality, then maybe it is enough just to say so. The additional claim that the new distribution is not more equal than the old one just seems (to me) wrong, and unnecessary.

Maybe this is actually to do with the properties of the (nominal) income scale, rather than with the structural property of inequality? You could certainly do things (I don’t know what things) to the income figures before you fed them into the Gini function.

If you really wanted to make the absolute size of the income spread matter more (a lot more), you could get a measure which is still scale-independent in the sense of unit-independent by subtracting the lowest income from all values before you started: then {11,12,13} would come out just as equal as {1,2,3}, and {10,20,30} would be much less equal, where Gini would make it the same as the latter and both of them less equal than the first one. It would also be what I suppose you could call ‘scale-independent’ in a different sense, that of not recognising a natural zero point on the income scale. But I expect that would give some pretty counterintuitive results too.

Or looking at one of the other toy examples, I suppose one question would be – from the initial situation of nine people on a dollar and one millionaire, let’s say there is a doubling of available income, (with available goods to preserve its purchasing power and whatever else you want to stipulate), and we can choose how to distribute the million dollars or so. How would it be distributed, if for some reason we wanted to preserve the current level of (in)equality exactly?

Would we distribute it equally? That would be highly salient, but we would then have 9 people on 101 grand and one on 1.1 m, and (I think) you would have to say that is much less unequal than the starting point.

But you would say distributing it proportionally to the existing dist would make things more unequal. So the solution(s) is (/are) somewhere in between – but where? And is there a generalised formula for working out how to do it?

Probably not very helpful. I’ll stop wittering on about it and get on with what I’m supposed to be doing.

Tim Wilkinson 10.05.10 at 3:55 pm

sorry, missed a couple of posts while producing that slab. Looks like the properties of the income scale to me. May I suggest making some clever adjustments to the income figures before feeding them to Gini?

Zamfir 10.05.10 at 3:56 pm

Sorry, that comment was intended earlier.

From your formulation, I get the impression you see the 50% of the urban people as a step up in an ongoing improving process, while the subsistence farmers got a one-time increase that won’t lead to more. Also, your description of “still subsistence farmers” suggest that the actual living conditions of these people haven’t increased a lot.

Isn’t it just the case that monetary income is bad way to measure the material well-being of subsistence farmers?

dsquared 10.05.10 at 4:19 pm

No, their actual conditions have almost certainly improved a lot – going from less than a dollar a day to more than a dollar a day makes a huge difference in terms of survival. But (and actually I think I now need to move to a fantasy alternate earth version of Sudan because I’m saying things that might not be true at all of real Sudan), having things get better isn’t the same as having them get more equal. I think that the intuitition is that the incentive for a farmer to try to become an urban resident is much bigger after the growth, and this is something with empirical relevance – urban magnet effects are associated with the early stages of development, aren’t they?

Lemuel Pitkin 10.05.10 at 4:30 pm

Isn’t it just the case that monetary income is bad way to measure the material well-being of subsistence farmers?

Right, I think this is where a big part of the criticism of the Gini is coming from. If we imagine some measure of total income that includes both monetary and non-monetary income, and if the non-monetary component is distributed more equally than the monetary part, then scaling up money incomes by an equal proportion across the board will leave the monetary-income Gini unchanged, but would increase the Gini for total income, if we could measure it.

In this case, the criticism isn’t of the Gini as such but of the income concept.

Sebastian 10.05.10 at 4:36 pm

“having things get better isn’t the same as having them get more equal. ”

This is definitely true, and conversely having things get more equal isn’t the same as having things get better.

That is why the focus on equality vs. the getting better part seems so counterintuitive to lots of people.

Lemuel Pitkin 10.05.10 at 6:15 pm

having things get more equal isn’t the same as having things get better.

There is an important strand of argument, as represented by The Spirit Level, that says past some threshold the only way things can get better, as far as income goes, is indeed by becoming more equal.

A per capita income of $15,000 might be a first very rough approximation for that threshold, tho the exact level is not so important as the point that the US and Western Europe are definitely past it, and sub-Saharan Africa and most of South Asia definitely are not.

Alex 10.05.10 at 8:45 pm

I think D^2 would agree that *losing* £x is much more significant for the bottom 10 per cent than it is for the top. I presume his attack on the housing benefit cuts will take this line (your contribution is expected).

Therefore it should work the other way round. But I do think that quite a few economic relationships might show different properties depending on the direction of change (of course, this is internalised in the notions of income and substitution effects).

And the stylised fact that the marginal propensity to consume is diminishing with regard to income – you can be rich enough that you can’t easily find ways of spending enough money, or that you have enough money to think about leaving it to your kids – would suggest that an extra quid for the poorest should count for more.

But I still want to kick Blair.

Peter Whiteford 10.06.10 at 1:31 am

Zamfir

“Ingvar Kamprad lives in Sweden

Oh no. He lives in Switzerland …”

My bad, I shouldn’t rely on what I find with a quick Google search.

Fortunately this is not central to my point, since Stefan Persson (the owner of Hennes & Mauritz) does appear to live in Stockholm and his wealth is still about 12 times the richest person in Argentina.

In addition, Liliane Bettencourt and Bernard Arnault appear to live in France (happy to be corrected if my subsequent quick Google searches are incorrect) where the Gini coefficient is around 0.28 and they appear to be much wealthier than anyone who lives in South Africa (Gini of 0.65 or so). (Note I’ m assuming that the ratios of rich people’s incomes across countries are the same as the ratios of their wealth, but this strikes me as conservative.)

So the conclusion to be reached is that an absolute distance measure of inequality gives different rankings than a Gini coefficient (or a ratio measure) and they must therefore be telling us something different.

D squared and others say that there is important extra information in the distance measure. But the distance measure has a lot of very undesirable characteristics. If you use this measure equally distributed economic growth increases inequality and equally distributed economic decline reduces inequality. However, presumably uniform inflation is OK from an inequality perspective since the purchasing power of different points is uniformly affected. This is analogous to comparing currencies across different countries, since as I pointed out earlier presumably we wouldn’t think it meaningful to say that Japan is more unequal than the USA because its currency has more zeroes (or that Italy reduced inequality when it shifted from the lira to the euro).

I also think that an implication of this approach is that every developed country had significantly increased income inequality between the end of Second World War and the 1970s, since at best what was seen was faster growth rates at the bottom than at the top.

Another problem with a distance measure is that it is based on two points –the bottom and the top and doesn’t tell us what happens in between. For example, let’s say that the incomes of the poorest and the richest (individual or even decile or quintile) stayed exactly the same but the middle class lost a significant part of their income share to those in the 8th decile. The distance measure completely ignores this.

On balance, these are among the reasons why absolute distance measures are regarded as very poor measures in the income distribution literature. Is the additional information worth the ambiguities and other problems? – I don’t think so.

dsquared 10.06.10 at 8:36 am

If you use this measure equally distributed economic growth increases inequality and equally distributed economic decline reduces inequality

I think this is only right on a definition of “equally distributed economic growth” which somewhat begs the point at issue. Myself and Brian’s point was precisely that if you start with an unequal distribution, and give an equal percentage increase to every point, then the distribution of the total increment to wealth isn’t equally distributed – it’s distributed exactly as unequally as the original distribution. On the other hand, an equal percentage decrease means that most of the burden of the overall decrement to wealth is taken by the rich.

I also think that an implication of this approach is that every developed country had significantly increased income inequality between the end of Second World War and the 1970s, since at best what was seen was faster growth rates at the bottom than at the top

I don’t think this is right – the condition for a reduction in the rich-poor gap is that the lower percentiles have to grow faster than the higher ones more than proprortionately to their income share minus one (I think). I bet this happened in a lot of postwar economies.

For example, let’s say that the incomes of the poorest and the richest (individual or even decile or quintile) stayed exactly the same but the middle class lost a significant part of their income share to those in the 8th decile. The distance measure completely ignores this

I think you’re arguing against a position not actually taken. Neither me nor Brian nor anyone else has claimed that the absolute distance is a good substitute for the Gini – we’ve simply used it in cases where it’s a good way of showing that the compression of the information in the histogram or Lorenz curve down to a scale-independent measure has thrown away useful information.

dsquared 10.06.10 at 8:43 am

(actually, the more I think about this, the more I take a view on the extreme epistemological and methodological left wing; I don’t think that “lack of ambiguity” is necessarily a desirable characteristic in something that’s meant to measure an inherently ambiguous and contested property. Similarly, the ease of comparison of Gini coefficients between different periods and countries is not a good thing, and so is scale independence. Scale matters in economics).

Zamfir 10.06.10 at 9:44 am

I think that is completely right. The irony might be that Gini-like simple numbers are more useful when people are not completely familiar with them. As long as people expect that any comparison of equality between countries and periods will be a complex document, there is no harm in using gini-numbers as part of that story, to illuminate a particular feature of the differences.

The trouble starts when the number takes the place of the complex, situation-sensitive document, and the document becomes background to the number.

Peter Whiteford 10.07.10 at 2:10 am

The condition for a reduction in the absolute rich-poor gap is that the lowest group(however defined ) have to have a ratio of income growth to the richest group that is higher than the ratio of the incomes of the richest group to the incomes of the lowest group. for example, if the richest group have incomes that are twice as high as the poorest, then for the absolute gap to fall then the poorest group have to have at least twice the rate of income growth as the richest. If the income gap is ten to one, then the growth ratios have to be at least ten to one.

derek 10.07.10 at 2:15 pm

I see I wrote:

“The Gini coefficient [is] better than less naive measures of well-being like GDP per head”

That’s not right. I was trying to desribe GDP per head as the most naive measure of well-being. I should have written “better than *more* naive measures of well-being like GDP per head”. I hate typos (brainos, rather) that reverse the meaning of my sentences.

Comments on this entry are closed.