As mentioned in a recent post, I got to go to Texas for a conference on Conservatism sponsored by Sanford Levinson. Unfortunately, that was the day some joker decided to call in a fake bomb threat. So we ended up evacuated and reconvened in Sandy’s living room. Which was congenial, actually. But no PowerPoint, so I didn’t get to use the cartoons I whipped up that were supposed to allow me to make some basic points in admirably compressed fashion. So let me lay that bit out.

Rawls, I argue – in a really long piece that I hope to post some time soon – has a blind spot for conservatism. It just isn’t clear where conservatisms and conservatives fits into his scheme for political liberalism. Are these ‘reasonable’ candidates for inclusion in an overlapping consensus or not? On the one hand, Rawls suggests he wants to set the bar pretty low. On the other hand, it’s not hard to see how conservatisms and conservatives could fail to pass crucial Rawlsian tests of reasonableness. I’m not going to argue about that right now (although you are welcome to pick a fight, in comments.) In my paper I emphasize that Rawls has surprisingly little to say, one way or the other. This produces an ambiguity. One of Rawls’ solidest anti-utopian credentials is his commitment to pluralism. This makes it seem as though he imagines, optimally, some hypothetical future in which something like the Democratic Party and something like the Republican Party – both philosophically spruced up in various ways – jostle and complete in reasonable, civil fashion. But, strictly, saying we need some buzzing, messy pluralistic public square is strictly consistent with saying that, ideally, we should abolish the buzzing, messy pluralistic public square we’ve got and elect a new one. That is, ideally, we should have a healthy mix. It obviously doesn’t follow that, ideally, we should have approximately what we’ve got now, since what we’ve got now is a mix.

I end up arguing that Rawls’ problem is not so much that he is stuck in some Harvard boutique liberal bubble – as his conservative critics would no doubt say – but that he has trouble doing ideal theory of partisanship, as it were.

This brings us to cut-rate New Yorker-style cartoon number 1:

Get it? As I said, one of Rawls’ clearest anti-Utopian credentials is his commitment to pluralism.. We aren’t going to make everyone sing from the same Hymn Book of the Good. But it’s a bit unclear whether this really is anti-utopianism because one of the main intuitions behind acceptance of pluralism is a sense that ideally there should be pluralism. It wouldn’t be me any more if I lose all my distinguishing characteristics and become one more angelic voice, singing the same tune. Even so: why insist on pluralism only of a Rawlsian sort, and to a Rawlsian degree? Here Rawls tends to offer an unclear mix of idealist and realist considerations – hence his use of the term ‘realistic utopianism’. Suppose we really pressed him on this. If you could really get what you think would be best – never mind about realist constraints (we’re in heaven!) – what would it be?

Obviously we aren’t going to say that everyone should sing in harmony in the choir. But it’s equally absurd to say that nothing should change. “Fight on, fare ever – there as here!”

Is it reasonable to say that, in an ideal – even just an optimal – world, no one would want to watch Fox News six hours a day? I would say: obviously so. But obviously imagining away the Fox News viewership, for purposes of doing ‘ideal theory’ is a very consequential step. (And conservatives needn’t retire to fainting couches and survivalist bunkers, in response to such a statement. We’re just saying: so long as people watch that much Fox, it’s unlikely that we’ll get society as a fair system of cooperation, in Rawls’ sense. Because the people won’t stand for it!) Rawls idealizes citizens as just and law-abiding, to a fairly high degree, for ideal theory purposes. Wny not just toss in: and they won’t be the sorts who want to watch Fox News all day. But that, even though it is less, seems like it is too much. Dictating taste in television is not what Rawls is all about.

This is funny because, one the one hand, you can’t expect people to give up what really matters to them, when they get to Heaven. Otherwise Heaven wouldn’t be the happy place we think it is. On the other hand, what could be the point of trying to write this stuff into the firmament, ideally?

Does this improve matters? Not obviously. After all, what’s the point of there being both liberals and conservatives, ideally?

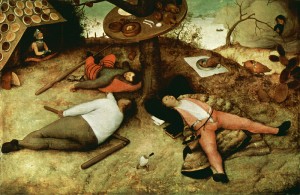

I actually didn’t draw this next one myself.

It’s Peter Brueghel. There’s an ancient utopian tradition that doesn’t get much philosophical traction despite the fact that it’s name – Cockaigne [see Brueghel link] – is cognate with Cuckooland, on whose clouds many philosophers are thought to dwell. Cockaigne is the place where, as Rawls would put it, the objective conditions for justice are not met. There is no scarcity. It’s a land of plenty. Pies on the roof. Brueghel is obviously objecting on the grounds that it’s a land of sloth and therefore rather disgusting. Hardly ideal. But, in defense of Cockaigne, a lot of fantasies about it are more active, leaving room for the triumph of virtue. Take the American version, the Hobo’s Utopia – “The Big Rock Candy Mountain”. Now why would there be cops and bulldogs at all if there’s plenty for all? Doesn’t make any sense, does it? But obviously it’s more fun to imagine cigarette trees plus stealing from them and getting away from the cops (who have wooden legs) and dogs (that have rubber teeth). The ideal political theory version of this, it seems to me, is a heaven in which there are liberals and conservatives, only your side has such an advantage that you are bound to win. Does Rawls offer us such a vision, in effect, in Political Liberalism? There will be conservatives, but, inevitably, they will be hobbled by the whole set-up?

[NOTE: in typing my notes for this part of my talk on my iPad I had a strange experience. I was writing something about David Estlund’s paper on ‘utopophobia’ but my iPad figured that was ‘hobo utopia’ – which was strange, because I actually was writing about hobo utopias, i.e. “Big Rock Candy Mountain”, but not at that particular moment. And my iPhone thought it should be ‘Holbo utopia’, which is something else. So my notes were a bit of a mess for a while there.]

What if we try to raise the tone of partisanship to a truly ideal degree by imagining, in effect, that when you die you get to pursue politics – because we all care about politics! – by pursuing a posthumous Ph.D in political philosophy at Harvard. (And Rawls is still alive and teaching. What could be better?) You get to be partisan, in effect, but only insofar as you adhere to an ‘ideal’ philosophy of one sort or another.

The problem is that it is unclear what pursuing ideal politics in this sense – partisanship about ideal theory, in effect – has to do with ideal theory of partisanship, if you see the distinction.

So that’s what the talk was about. Just wanted to get these cartoons posted. Make of them what you will.

{ 43 comments }

J. Otto Pohl 09.24.12 at 10:50 am

I do not understand the the left wing cult that seems to have formed around Rawls. It is a big step down from Marx and Lenin. I can read Marx and even Lenin without falling asleep. I can also see where a developmental dictatorship like the USSR might be attractive to those of an extreme utilitarian bent. Sure 10% of the population is brutally exterminated in the process, but the descendants of the 90% that do survive are much better off materially. When applied to really poor countries like the Russian Empire, China, and Cuba the model has a certain appeal. But, Rawls doesn’t even offer that as far as I can see. His theory is only applicable in the already advanced capitalist liberal and social democratic states. It offers no promise of development for the vast majority of the world’s population living in poor and underdeveloped countries. It is just a plaything of the idle academic bourgeoisie in already rich countries.

Phil 09.24.12 at 11:22 am

Could have been worse – could have been Habermas. Although you’d really have to read the Notes on a Discussion to appreciate why.

REFERENCES

Various authors, Notes on a Discussion of the Preconditions of an Adequate Discussion of the Criteria of Appropriateness of the Discussion of Criteria (3 vols), 2012. This symposium was of course a response to my (if I say so myself) ground-breaking onslaught on the received wisdom, Adequate Discussions and the Preconditions for an Appropriate Discussion of Their Criteria in the Case of Habermas and Rawls, which itself responded to the Identifying the Criteria of Adequacy in Extending the Discussion of Habermas and Rawls (I won’t embarrass the author by naming him/her), a woefully inadequate attempt at defusing the challenge laid down by my own Habermas and/or Rawls: The Case For Extending The Discussion (And The Case For Saying, Sod This For A Game Of Soldiers, I’m Going To Read Some Stephen King Instead).

Stuart 09.24.12 at 11:27 am

Its built into the structure of contractualist accounts of justice- they have to exclude those who believe there is a non-political source of justice that trumps whatever rules (would) emerge from the need for political compromise.

Rawls’ problem with conservatives mirrors exactly Rousseau’s problems with Catholics. i.e. he has built a supposedly realizable utopia that rests upon a measure of ‘toleration’ that excludes half the subjects of any likely polity.

“Each man may have what opinions he pleases, without it being the sovereign’s business to take cognizance of them..BUT…there is a purely civil profession of faith which the Sovereign should fix the articles.” These articles include “The sanctity of the Social Contract and the laws, its negative dogmas I confine to one, intolerance.” (SC 3.8)

We MUST tolerate difference of opinion, but the one thing we can’t tolerate is difference of opinion on is where justice gets its sanction. I think Rawls ‘gets’ that some Conservatives will never be able to accept this, he is just certain that they are not possible partners in a system of Social rather than Divine justice.

arbitrista 09.24.12 at 11:29 am

Any chance of publishing a working draft of the paper? It overlaps considerably with a Rawls project I’ve been tinkering with and I’d love to read your argument in detail.

@ J. Otto Pohl: You’re comparing apples and oranges. Trying to figure out what the most just feasible political community might look like is a different question from how to improve the material conditions of people in very poor countries. One is about justice, and the other about wealth.

Daryl McCullough 09.24.12 at 11:53 am

I think that it’s a mistake to view pluralism in terms of liberals vs. conservatives. Both liberals and conservatives are actually coalitions of people with different political agendas, and it’s an artifact of the way politics is done that we pretend that everyone is one or the other.

The more interesting kind of political plurality is really the various “special interest” groups that everyone seems to think are so harmful to political discourse. Some people care more about the arts than other people do. Some people care more about the environment, or income inequality, or sexual inequality, or low taxes, or crime, or abortion, or freedom of speech or whatever. Even if we are all dedicated liberals, that doesn’t end the debate over these issues. Even if every issue has a clear “politically correct” position associated with it, there will still be squabbling over how much priority to give to each issue. Part of the squabbling is going to be about how to divide up scarce resources: Do we spend more money on health care for the poor, or on protecting the environment? Part of the squabbling is going to be about deciding between two or more incompatible notions of what the ideal is.

J. Otto Pohl 09.24.12 at 11:54 am

arbitrista:

Wealth can not be separated from justice so easily. If you have systems of resource distribution in which small groups of people like for instance academics in rich countries have a disproportionate share of wealth while other people are literally dying due to a lack of material resources then you certainly have a system lacking in justice. Indeed the greatest forms of injustice are precisely those where the elite use the state as a mechanism to allocate wealth to themselves while leaving the majority of the population immersed in poverty. More so than lack of political freedom, things like colonialism and apartheid were considered unjust because they allocated the majority of material resources away from the indigenous majority population leaving them impoverished in the process. Is it really not a matter of justice that people like Holbo live incredibly privileged lives while other people die because they can not afford malaria medicine that costs 75 cents?

aepxc 09.24.12 at 12:13 pm

A utopian pluralism would be one in which disagreements could be settled through experimentation rather than debate. A place in which groups of the people who have dreamed up a system with a different set of tradeoffs could splinter off and set it up, attracting or losing members according to how successful their ideas pan out to be. That way you could have progress without the vitriol.

Daryl McCullough 09.24.12 at 12:43 pm

aepxc,

Part of the reason for acrimony in politics is the unfortunate fact that we only have one world to play with. Some decisions are local, and different communities could try their own experiments. But other decisions, like whether and how to deal with global warming, international tensions, global trade issues, etc., can’t really be subject to experiment.

I do wonder why there isn’t more experimentation at the local level in the US. It seems like communities could experiment with drug legalization, communism, abortion bans, gay marriage, etc. But in practice, such decisions are always made at a larger scale–the state or the federal level, rather than individual communities.

bob mcmanus 09.24.12 at 12:58 pm

5: This

We are a collectivity of individual (rarely, actually) overlapping and conflicting interests, and it might more useful to model and study concrete instances of local politics before we go global and meta-meta.

Do we allow vendors in public parks, how many and how regulated? How is this to be decided?

It is interesting then to see how global and meta-arguments (urbanist, free-marketer) are used as authority in concrete disputes.

Barry 09.24.12 at 12:59 pm

J Otto Pohl: “I do not understand the the left wing cult that seems to have formed around Rawls.”

It’s the USA, whee libertrianism is considered to be intellectually respectable.

Barry 09.24.12 at 12:59 pm

Wheeeeeeeeeeee! :(

bianca steele 09.24.12 at 1:03 pm

Rawls, I argue – in a really long piece that I hope to post some time soon – has a blind spot for conservatism.

This sound interesting. Is it controversial? If pressed, I’d probably have to confess that what I know of how Rawls is thought of by other people is drawn from limited evidence.

bianca steele 09.24.12 at 1:05 pm

Which Barry points up: is the point of Rawls that he defends something like libertarianism, or is the point of Rawls that even if you’re something like a libertarian, you need redistribution too?

J. Otto Pohl 09.24.12 at 1:28 pm

10

I thought Dr. Holbo taught in Singapore which I am pretty sure has never been ruled by libertarians.

bianca steele 09.24.12 at 1:31 pm

The bit where you argue for Rawls’ pluralism w/r/t the good is interesting too. It seems obvious to me, but why wouldn’t someone–say someone who took naturally to all that pearly gates imagery–understand the good as obviously only one thing? He can’t possibly mean that there’s only one good life but people who want to be benighted and live in squalor can do so as they like.

LFC 09.24.12 at 2:22 pm

Haven’t had a chance yet to read the OP carefully but scrolling through the comments I find bianca: is the point of Rawls that he defends something like libertarianism

I’ve said this before but it doesn’t seem to have sunk in:

Rawls does not defend libertarianism (or something like it)

Once more:

Rawls does not defend libertarianism

Once more:

Rawls does not defend libertarianism

is that enough times?

if you don’t want to read Rawls himself there are numerous primers available that will give you the basics.

bianca steele 09.24.12 at 2:35 pm

LFC: You don’t actually accuse me of asserting what you think is the horrible, benighted belief that Rawls defends libertarianism, or even that it’s likely that Rawls defends libertarianism, but could you read my comment again? I think what I meant was pretty plainly expressed.

1. Adding “LFC says so” to my evidence isn’t all that convincing. 2. I think that if acceptable arguments from Rawls are necessarily defenses of something like libertarianism, as has seemed at times to be the case on CT and elsewhere, granting that “CT commenters say so” isn’t great evidence, it is hard to see how Rawls is not a defense of libertarianism. In that case, certainly, no one who wished not to defend libertarianism would spend a lot of time on him. My question’s whether that is the case.

LFC 09.24.12 at 5:25 pm

bianca:

“I think that if acceptable arguments from Rawls are necessarily defenses of something like libertarianism…, it is hard to see how Rawls is not a defense of libertarianism.”

The problem is the word “if”: Rawls’s arguments aren’t defenses, “necessarily” or otherwise, of something like libertarianism. Therefore it is not “hard,” but on the contrary easy, to see how Rawls is not a defense of libertarianism.

Neither the Rawls of Theory of Justice (which I’ve read) nor the Rawls of Political Liberalism (which I haven’t read but as I understand it from reading things about it) is interested in defending the substance of libertarianism, i.e., the view that the state shouldn’t do much of anything except enforce contracts and a couple of other things. He sees more of a role for the state than that, even if, as C. Bertram suggests in his “predistribution” post above, it’s only tinkering now and then with the “basic structure” of society. Thus I tend to get a mite impatient w these attempts to tie Rawls to libertarianism, attempts which, as far as I can tell, mainly are a result of comments by one commenter. However, if I’m wrong about that and there have been other comments or posts here on similar lines, I’d also be a bit impatient with them.

LFC 09.24.12 at 5:49 pm

From the OP:

But, strictly, saying we need some buzzing, messy pluralistic public square is strictly consistent with saying that, ideally, we should abolish the buzzing, messy pluralistic public square we’ve got and elect a new one.

Isn’t it fairly clear that Rawls thought the public square as currently set up in the US is not only buzzing and messy but fatally contaminated by the effects of money in politics (even worse after Citizens United, of course)? Perhaps the OP should have nodded in that direction. OTOH, I don’t fully understand the OP’s worry about whether Fox News watchers count as “reasonable.” To be a little flippant: if their conception of the good is watching Fox all day they’re going to be too occupied to do much real harm except on election day. So R. doesn’t have much to say one way or the other about whether conservatives pass his test of “reasonable” — I can’t get too excited about that. BTW, what if someone read Burke six hours a day instead of watching Fox six hours a day? Would that person count as “reasonable”?

LFC 09.24.12 at 5:51 pm

Or Strauss for six hours a day, or fill in the blank… Ayn Rand might be pushing it, I guess…

Substance McGravitas 09.24.12 at 5:55 pm

Last time I spent a while in America there wasn’t a US news station that was showing more news than Fox. So I watched it, imagining I could glean the real news through the filter.

Jeffrey Davis 09.24.12 at 7:33 pm

Isn’t the acceptance that pluralism is unavoidable different than finding it ideal?

LFC 09.24.12 at 7:58 pm

arbitrista @4:

Trying to figure out what the most just feasible political community might look like is a different question from how to improve the material conditions of people in very poor countries. One is about justice, and the other about wealth.

In this case I agree with J. Otto Pohl that the questions of justice and wealth can’t be kept so separate. What Pohl misses, though, is that there’s been a lot of work, going back to the ’70s but esp. in more recent years, trying to extend Rawls’s views, in some way or other, to a global scale. (I should/would probably defer to C. Bertram’s knowledge about this. Mine is sort of out of date.)

John Holbo 09.25.12 at 2:51 am

“I think that if acceptable arguments from Rawls are necessarily defenses of something like libertarianism, as has seemed at times to be the case on CT and elsewhere”

As LFC says, Rawls is clearly not a libertarian. I am not sure how it has ever seemed otherwise, here or elsewhere, but clear such seemings from your mind forthwith. They are erroneous.

“Isn’t it fairly clear that Rawls thought the public square as currently set up in the US is not only buzzing and messy but fatally contaminated by the effects of money in politics (even worse after Citizens United, of course)? Perhaps the OP should have nodded in that direction.”

I think the post did nod in that direction. If the problem is money, then the ideal would be something like the Democrats and the Republicans, just spruced up to reduce the unfortunate effects of money. In general, the question is whether what we need is, in effect, an improved version of what we’ve got, or something quite different.

“BTW, what if someone read Burke six hours a day instead of watching Fox six hours a day? Would that person count as “reasonableâ€?”

Obviously Rawls is going to be embarrassed if he has to rule out Burke scholars, and for that reason he wouldn’t want to get on the FOX news slippery slope, even though it’s not so clear that Burke actually can pass Rawlsian reasonableness standards. (Is it reasonable to think so much more highly of Marie Antoinette than her hairsdresser? ‘Reasonableness’ for Rawls is a matter of fair dealing, and it’s not clear that Burke’s devotion to class divisions is really consistent with that.) Rawls is ruling out people who aren’t prepared to live by a ‘fair’ system of social cooperation, provided others are as well. If someone like Corey Robins is right that conservatives are motivated by a desire to preserve private regimes of unjust privilege, then conservatives flunk the reasonableness test. But this is, I think, not the result Rawls wants. He wants the overlapping consensus to be a space within which conservatives and liberals can work out their differences reasonably, not a bubble that excludes conservatives. But it’s not clear he isn’t committed to the latter by his conception of ‘reasonableness’.

John Holbo 09.25.12 at 2:54 am

“Isn’t the acceptance that pluralism is unavoidable different than finding it ideal?”

Yes. Strictly Rawls only says its unavoidable, but it seems to me that his views are inflected by the fact that he also regards it as ideal.

js. 09.25.12 at 2:56 am

I’m inclined to think something along these lines. Though perhaps for reasons rather different than yours; and I’m not sure I’d necessarily say “blind spot”. Anyway, I think I’d approach it this way:

It seems to me that the Rawlsian justificatory procedure can’t actually handle communitarians, or perhaps certain sorts of communitarians. (I realize this is not an uncontroversial thesis.) Roughly, if in the original position you’re asked to choose between a basic structure that’s liberal (in a suitably general sense) vs. a basic structure that’s set up, inter alia, to promote a (or some specific) communitarian ethos, it’s not clear that you would or could come to a settled rational preference. Among other things, such a consideration would or should destabilize your conception primary social goods. (So also, the response that a liberal society would afford the opportunity for sub-communities with a strong communitarian ethos, subject to relevant constraints, isn’t going to be satisfactory, because once you take this kind of question seriously, it would plausibly tend to unsettle how you conceive of your conception of the good in relation to the basic structure.) And if you’re a committed communitarian, trying to achieve reflective equilibrium would only seem to make the problem worse. Etc.

Anyway, the point is: I think it’s not implausible to think of at least certain forms of, or aspects of conservatism, as species of communitarianism. I’m not here primarily interested in contemporary Republicans or the modern American right. Even leaving it and its particular pathologies aside (FOX News, really? Obviously, no one who counts as rational according to Rawlsian strictures—let alone reasonable—is going to watch it. Ever.), anyway yeah, leaving those peeps aside, I do think there’s a serious question here, and I do think it cuts deeply into questions of how to think about ideal value-pluralism (not so sure about the specifically “partisan” business).

William Timberman 09.25.12 at 4:01 am

It seems to me that an improved version of what we’ve got would indeed be something quite different. Must be something quite different, since the pit we’ve fallen into has been implicit from the beginning. I’m thinking of the wrestling matches of the Enlightenment, the outcome of which found its most concrete real-world expression, I would argue, in the U.S. Constitution, specifically in its attempt to balance the competing interests of the day. And if I’ve read the Federalist Papers and De Tocqueville’s musings correctly, the architects of that real-world expression were well aware of its fault lines, and did a fair job, if not a perfectly prophetic one, of imagining the stresses that the future might bring to bear on them. They were hopeful, these architects, but none of them were unqualified optimists.

Of course, once something is reduced to Holy Writ, as the Constitution has been in the U.S., it’s all that much easier to falsify, or to evade its obligations. In any event, if we’re to imagine our way out of the wreckage of the Eighteenth Century’s attempt at a rational novus ordo seclorum, we need to pay attention to the spirit rather than the concrete mechanisms of its politics. We also have to take serious account of what the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries should have taught us about how easily the powers unleashed by the rationality of the Enlightenment can be usurped by the irrational. The isms and the wars of our immediate predecessors have been banished temporarily, but what inflicted them on us in the last instance is still out there. We need to extend ourselves beyond what we already know if we’re to deal with their future manifestations. (It’s not that it wouldn’t help to stop electing apologists, nest-featherers and morons to public office; it’s that they’re a symptom rather than a cause.)

LFC 09.25.12 at 4:16 am

John Holbo @24:

Thanks, I understand better now what your argument is about Rawls and conservatism and ‘reasonableness’. I’m not up enough on Rawlsian ‘reasonableness’ to have an opinion on this myself, but I do get what you are saying now.

Bruce Wilder 09.25.12 at 10:18 am

I don’t think Rawls has a blindspot for conservatism; I think he sees it foursquare, takes aim and fires. The whole point of using the original position to define justice as fairness is to disallow vested interest conservatism, and any principles or philosophies, which function as rationalizations of vested interest conservatism. In his view, the Social Contract standard, of defining “fair” as principles chosen from behind a veil of ignorance, entails (he believes) universal endorsement of egalitarian social cooperation for mutual benefit. Conservatism of the what’s mine is mine, and what’s yours is negotiable variety, conservatism that favors hierarchy and domination as means and purpose for organizing social cooperation, is presumed to be deprecated by every reasonable person, from behind the veil of ignorance, and conservatism, as such, appears only in the corruption of actual politics practiced with the knowledge of particular self-interest and the possibility of overpowering opposition. There’s no possibility of an ideal society or an ideal politics; the ideal is the concept of fairness, which he hopes will guide and redeem an actual politics and political society.

Pluralism is a liberal desideratum because liberalism is the philosophy, which doubts that it knows what is right, at least in concrete terms. So, an ideal liberal society, in which all political discourse has collapsed into idealized liberal principles, is something of a contradiction. No actual legislature can enact laws from behind a veil of ignorance, nor can a judiciary arbitrate disputes, a priori. Politics has to discover how to organize society, in a world informed with the knowledge of good and evil, and particular situations, self-interest and power.

A fundamentally conservative, aka authoritarian, society could suffer a collapse of its political discourse. In fact, that’s what an authoritarian, as opposed to liberal, society is: a society in which deliberation on principles and rules has ceased, because conflict and negotiation has been resolved by the exercise of authority and power, in expedience. A liberal society seeks to perpetuate conflict and negotiation, ad infinitum, by means of deliberation (and in that deliberation, disinterested principle is persuasive), where a conservative society seeks to resolve the social conflict entailed by social cooperation into harmonious hierarchy, and replace deliberation and negotiation with authority and authority’s expedience.

So, while a liberal may reason from a concept of fairness, which abstracts from individual self-interest, the liberal does so in a real and messy world, introducing such an ideal as a guidepost, for arriving at rules and judgments through deliberation among equals. There’s an underlying presumption, I think, that a world of pure conservatism, where might makes right and no concept of justice apart from the concrete, situational good of the individual or individual-in-a-family can be conceived, is not functional; pure conservatism is a Hobbesian world without leviathan, but as soon as leviathan appears, the erosion of that conservative world into a more liberal world begins, as rationalizations of the role of leviathan emerge, and continue as society’s control of leviathan, as well as leviathan’s control of society, comes into dispute.

So, yes, a vested interest conservatism and its authoritarianism is the enemy of a liberal conception of democratic deliberation guiding the organization of society.

To me, the standard of heavenly utopianism is “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need” — a state in which society no longer has to balance the distribution of benefits from social cooperation, against the need to call into operation the social cooperation that generates those benefits, with incentives and discipline. To me, Rawls does not do a particularly good job of outlining political deliberation over the organization of social cooperation, where the rules governing the incentives and discipline that drive production may be in conflict with preferences regarding the claims or suffering of those, who may not contribute much to production. Rawls is very big on honoring the plans and aspirations of the individual, but not necessarily all that clear on how we get people to do that stuff called work, that no one really aspires to do. It does seem to be that one could have a thoroughly liberal political society in which both right and left are liberal in Rawls’s sense, and the “conservatives” (who are just right-handed liberals) are arguing for more personal responsibility, discipline and less social insurance (and how do we know that there are no risk-lovers behind the veil of ignorance anyway?), while the left-handed liberals are the bleeding hearts, who want more generous social insurance, as a consolation prize for the ugly or handicapped, and the victims of accidents. American political economy circa 1970 came pretty close to that kind of division between right and left, in a political discourse in which everyone claimed to be a philosophical liberal, and justified their desiderata, in liberal terms; Nixon always claimed that he shared the goals of liberals — he just wanted to be smarter and more efficient in pursuing those goals.

Circa 2010, it is much more difficult to see what a right-left division of opinion in a thoroughly liberal society might look like, or why Rawls might seem to anticipate such a peculiar (to us) chimera as a conservative liberal.

Pseudonymous McGee 09.25.12 at 8:09 pm

I spent a lot of my undergrad and MA studies discussing Rawls (not by choice, but I did get a lot out of it), and I was somewhat puzzled as to why he was such a Big Deal in North America. I agree with the flow of comments here that he was most certainly not a defender of libertarianism; in fact my own reading of Rawls revealed potentially vast mandates for intervention to defend economic and environmental commons (largely on future-generations-regarding grounds).

BUT… does the answer for Rawls’ popularity in America have something to do with the intellectual culture surrounding the “Holy Writ” status of the Constitution, perhaps? I’m not suggesting that an explicit belief in the completeness and infallibility of the US constitution is pervasive among American scholars, but the notion that the Right Answer is discoverable in the text as received seems to be woven into fabric of much structural political justice talk. It seems to me that the endless speculation on conditions and arrangements afforded by engaging with Rawls’ work bears some parallels to the contortions of those who insist extracting exhaustive right guidance from a finite and limited text by means of exacting interpretation.

Shorter version: maybe there are many political theory scholars with law degrees who find that Rawls’ methods of articulating prescriptive conditions map easily onto learned styles of legal thinking.

But people with law degrees are nice too. And Rawlsians. Just sayin’

LFC 09.26.12 at 2:00 am

Pseud. McGee @30:

As is fairly well known, Rawls was a Big Deal, to use your phrase, and not just in the U.S., partly because TOJ revived normative pol. theory at a time when many had assumed it was basically finished. As to your specific suggestion (a connection to constitutional interpretation), I don’t know; my sense is that some non-Americans perhaps tend to exaggerate the place of the Constitution in U.S. political culture but that would be another topic.

btw/fyi: Ch.6 of D. Rodgers’ prize-winning Age of Fracture (2011) discusses Rawls and others from an intellectual historian’s standpoint. (Have the book out from the library but have only dipped into it.)

William Timberman 09.26.12 at 2:56 am

Nor to me, but certainly he’s not alone in that. An authoritarian society is stable only so long as it isn’t impinged upon by forces it hasn’t anticipated, which is to say that, under modern conditions, it can’t be stable for very long. The Soviet Union probably defined the outer limit, at least for large, complex societies. Rather smaller North Korea may do better, but that isn’t looking as likely today as it did ten years ago. China by comparison, is a cauldron, one so large that everyone who looks into it seems to see something different.

Why on earth, given all the above, the powers-that-be in the United States seem determined to screw up their courage for one final dance with authoritarianism is more than I can understand. Is a future without aircraft carriers really that daunting ?

And Europe…what is one to make of Europe? If you read the contributions to Project Syndicate, your choices are limited: 1) a posse of assured technocrats with a sinecure at one or more of a half-dozen Bruxellian agencies, who aren’t at all worried, 2) futurist

wackosdreamers like Joschka Fischer, or 3) outright pessimists, which in PS terms means that they think somehow we should let somebody, somewhere vote on all this, or we’re doomed. Muddle-through, perhaps, for Europe then, at least if the other shoe doesn’t drop. An Israeli nuclear strike on Natanz or Bushehr, now that would separate the sheep from the goats, wouldn’t it?js. 09.26.12 at 3:37 am

Well, yeah. But that’s also not his topic, really. Rawls assumes a market economy (though he allows for collective ownership of the means of production). So I suppose he assumes that people work for whatever sorts of reasons people work in market economies. But maybe you’re thinking: given the assurance of a “reasonable social minimum”, people will be dis-incentivized to work (or something?). But look, Rawls, in TOJ, sets things up in very particular ways. He’s doing ideal theory—in one sense at least. So he assumes strict compliance. He has arguments against free-rider problems—arguments that are not half-bad, so to speak. Etc. So yeah, ultimately, he’s not worried about this kind of problem. But given what he’s doing, why should he be?

Two points of clarification: (1) I have no particular axe to grind here. My own views are way left of Rawls’. That said, I think it would just be stupid to deny that A Theory of Justice is simply a magnificent achievement. As LFC points out (sort of), there’s simply nothing remotely comparable, at least in Anglo-American political philosophy, in the decades prior. (2) Above, I’m only talking about TOJ; Political Liberalism I’m a lot less hot on, in more than one sense. (I’m also teaching TOJ right now, so that helps.)

J. Otto Pohl 09.26.12 at 9:00 am

30

I think you are right about the textual analysis. But, I think it probably is more a secularization of religious impulses than anything to do with the US constitution. If you are an atheist like most Rawls cultists then you can no longer do exegesis and hermeneutics on Bible passages. In the wake of the humanitarian disasters of the USSR, China, and other socialist states the default religious texts of the Left, primarily the writings of Lenin became too discredited for a lot of squishy, but oh so “hip” American academics to embrace. So the milquetoast of Rawls has replaced both the scriptures of the Bible and those of Lenin. So yes there is something to it about being a “religious” text for people who no longer believe in either God or Revolution. But, both God and Revolution are far more interesting than Rawls who remains the most boring writer ever in the history of the world.

LFC 09.26.12 at 1:08 pm

A few things:

1) I should have mentioned Patrick O’Donnell above @23 as someone who is knowledgeable about the global distributive justice lit.

2) There’s a (political scientist) blogger who has been posting some stuff recently about weighted voting schemes (i.e., the worse-off get more voting power). He frames it as sort of an extension of Rawls. (I’m quite dubious that Rawls himself would have liked it.) It’s a little off-topic here, but I can supply the link if anyone is interested.

3) J. Otto Pohl @34: This comment is a bunch of crap, even by J.O.P.’s standards. The notion that atheists can’t do Biblical exegesis would be amusing if it weren’t so ludicrous. Leftish US academics embraced various writers but Lenin wasn’t high on the list. (And btw, stop calling China and the former USSR “socialist states.”)

J. Otto Pohl 09.26.12 at 1:33 pm

3)

LFC well I suppose atheists could do Bibical exegesis, but my guess is most of them don’t have much interest in it. They would rather examine their own secular texts.

Lenin is the foundation of modern socialist thought. Without Lenin there is no way to bridge the huge gap in Marx’s writing about how to get to socialism especially in states that have not yet become industrialized. It certainly was not going to happen on its own without a vanguard. Every single socialist state and quite a few non-socialist states such as Turkey, Taiwan (ROC), India and various states in Africa were significantly influenced by the Soviet example.

China under Mao and the USSR were socialist states. The state owned and controlled the means of production. Indeed the USSR was a highly successful socialist state in bringing about industrialization, urbanization, literacy, and a relatively high material standard of living in some of the poorest areas of the world in a short period of time. But, the only way to make such changes is of course through extreme state violence. Cuba is an interesting exception and the reason appears to be that the people who would have resisted such changes all fled to Florida thereby eliminating the need to physically liquidate them as a class.

bianca steele 09.26.12 at 2:12 pm

LFC:

Fair enough. I’m assuming, for purposes of the comment, a kind of archaeological argument, whereby, if an argument that mentions Rawls with the implication that he’s an authority, the inevitable response will be a reminder that one has chosen an argumentative point of view in which it’s necessary either to defend libertarianism or to admit that one has inadvertently appeared to do so and had made a mistake. Obviously, the need or advisability of using blog comments as a kind of authority in themselves is open to debate (and creates other uncomfortable questions, far far far off topic, like whether it’s “OK” to post as a woman or as an obviously non-native English speaker or c.).

LFC 09.26.12 at 3:07 pm

J. Otto Pohl @36: We can argue the question of whether China and the USSR are properly called socialist states somewhere else, though I’m not sure it would be a good use of time. But to do that here would completely derail the thread. Sorry I even raised it here.

bianca steele @37: I am having trouble following this. I would urge you to re-read the opening of J. Holbo’s comment @24.

bianca steele 09.26.12 at 3:21 pm

LFC:

You’re right, you’re really not following me. I’m suggesting that the definition of “libertarian” is a convention, and as such depends on how the word is used by people. If people stretch the meaning of “libertarian” to mean Rawls, I can’t talk to them without granting their definition some influence. That their definition of “libertarian” may be inconsistent, or wrong in some other way, doesn’t change the fact that I can’t talk to them without granting their definition some influence.

For myself, I’d be happy dropping back to the–probably more easily answered–question whether Rawls is better thought of a as liberal (American) or a liberal (Anglo-European).

LFC 09.26.12 at 3:57 pm

bianca steele:

This will be my last comment on this. I accept your statement that you have read people commenting on blogs who have referred to Rawls as a libertarian. Those people don’t know what they’re talking about; I refer you again to J. Holbo’s comment @24. The definition of “libertarian” is not “a convention” in quite the way you seem to mean. Rather, the word “libertarian” has a reasonably determinate meaning. People make a mistake if they write on a blog “Rawls is a libertarian.” Of course we all make mistakes now and again. This just happens to be a pretty basic mistake.

Rawls is also not a liberal in the European sense of the word “liberal”. You raised this very question before in an earlier CT thread and two people gave you the same answer: one of them was myself and the other was the commenter who signs himself or herself js. You’ve apparently forgotten that exchange.

As I said, this is the last comment I intend to write on this issue.

bob mcmanus 09.26.12 at 4:08 pm

39,40:Not intending to jump in this too deep, but Cato blogger Will Wilkinson has done a lot of work trying to reconcile (mashup?) Rawls and Hayek with a degree of success unknown to me. Perhaps he moved Hayek closer to Rawls? But googlin “Rawls Hayek Wilkinson” will get a page of links. WW calls it a “Fusion”

Not that Hayek was a libertarian, but I think Wilkinson is.

Bruce Wilder 09.26.12 at 5:45 pm

William Timberman: “An authoritarian society is stable only so long as it isn’t impinged upon by forces it hasn’t anticipated, which is to say that, under modern conditions, it can’t be stable for very long.”

I’m not so sure. I think an authoritarian society can sink, and sink, and sink, for a long, long time, provided there are no competitors in the vicinity, able and willing to do the impinging. The basic relation of an authoritarian society is vertical: domination. It economizes on haggling, negotiation and conflict — at least along vertical axes, and the elite economizes on knowledge and responsibility, so to speak. Ancien regime France might have stumbled along for another century, if not for the competition with Britain, which highlighted her relative decline and provided the fortuitous forbidden fruit of the American Revolution. Look at North Korea, flirting with famine, lodged in the untouchable deadspot of political gravity between 4 of the most powerful countries in the world, and neighboring one of the richest, but . . . there it is.

The noise and time spent in negotiating conflict really does feel like a waste, a deadweight loss, which people tire of and want to minimize. A liberal society, by its insistence on egalitarian principles, parallels a lot of vertical relations with seemingly artificial horizontal conflicts — e.g., unions of subordinate employees negotiating with management — which seems to multiply the conflicts. And, the vertical relation is no fun, either; no one likes taking direction or having to follow detailed rules, which are actually enforced. And, a liberal society, by keeping the ruling elite competent and honest, keeps that rule-making and enforcement active, . . . and annoying.

Adjusting to change creates strains in the liberal society, which can actually increase the appeal of authoritarianism. I see it in the local politics of zoning in my neighborhood; as the population density increases, the rules requiring garages seem burdensome, as people convert the garages into additional living space. Changing the rules creates a political context in which those, who want to resist change can stymie the process of adapting to the changing reality. People get mad at the inspectors, and accuse the city of using the rules to extract additional revenue (which is true, the city, strapped for funds, does this). Non-enforcement and corruption begins to have appeal. Libertarian rhetoric, conveniently, suggests that we don’t actually need any of these silly rules. Disinvesting from the rules seems like a better way forward than revising the rules.

An authoritarian society promises, manifestly, to eliminate a lot of seemingly unnecessary “horizontal” conflicts, particularly those manufactured from vertical relations. The subordinates can no longer sue in court or join a union. And, implicitly, it promises corruption and incompetence, which feels like freedom to the powerful and resourceful, a multiplication of opportunities to make money fleecing the rubes.

So, I don’t have any difficulty at all seeing why the powers-that-be are moving full-steam-ahead toward authoritarianism. The elite think there’s money to be made, and their lives (though not our lives) will be easier. The game of three-card monte that our political discourse has become, in which the libertarians (Republicans) and neoliberals (Democrats) play as shill and dealer, hide the corruption and the fleecing from the mark, the American People.

William Timberman 09.26.12 at 7:10 pm

Bruce Wilder @ 42

I can’t fault your analysis of what is, but I can, I think, argue with your limits on what might be. Daydreaming, I imagine painting interstices, man, it’s all about the interstices between the paisleys on a modern rejiggeration of Kesey’s Magic Bus. I wonder at the pity that arises out of nowhere as I watch poor President Obama, perched on a stool in the Univision studios, doing his best to impersonate the expected icon of stability and good sense, which is surely less than what he had every right to expect his imagination, his curiosity, and above all, his finely-honed ambition would lead him to.

Because they have to move, things will move, and dousing everything that threatens your blocked intellectual bowels with pepper-spray or hellfire missiles can never afford you the confirmation that it seems to promise.

But enough with the hippie vapors of my youth. The appeal of authoritarianism is its promise of control over anything that threatens to become uncontrollable. The problem is that control as an ideology is sealed at both ends, closed to both past and future. In terms of military strategy, once you build a fortress, you’re immobilized, and even if you’re spies are good enough to tell you everything that’s going on in the countryside, you’re left without any way to analyze its significance, or to respond to it in context. To put it another way, whether sooner or later, anything that can’t bend will be broken, and given the forces in play today, I’d bet on sooner.

Comments on this entry are closed.