In his (relatively) new gig as business and economics correspondent at Slate, Matt Yglesias is really churning out lots of material. Often, it’s useful and insightful, but, inevitably quality control is imperfect. Arguably, there’s still a net benefit from the increase in output, provided readers apply their own filters. Nevertheless, I got a bit miffed by this post, which makes a mess of a topic, I’ve covered quite a few times, namely the question of whether US middle class living standards are declining as regards services like higher education.

As I’ve pointed out, the number of places in most Ivy League colleges has barely changed since the 1950s, and many top state universities have been static or contracting since the 1970s. In addition, the class bias in admissions has increased. College graduation rates have increased modestly since the 1970s, but an increasing proportion of post-school education is at lower-tier state universities as well community colleges offering only associate degrees.[1]

(Added in response to comments): Given static numbers at the top institutions, increasing populations, and a reduced share of admissions going to the middle class, education at the kinds of colleges usually discussed in this context (the top private and state universities) is an example where the middle class (roughly, the middle three quintiles) are getting less than they did 40 years ago. They’ve substituted cheaper second-tier and third-tier institutions where tuition, while rising fast, is much lower than at the Ivies, top state unis etc. But the chance of getting into the upper middle class (top quintile) with a degree from these schools is correspondingly lower. So, education as a route out of the middle class and into the top quintile is less accessible than forty years ago – this is leading to a reduction in already limited social mobility.

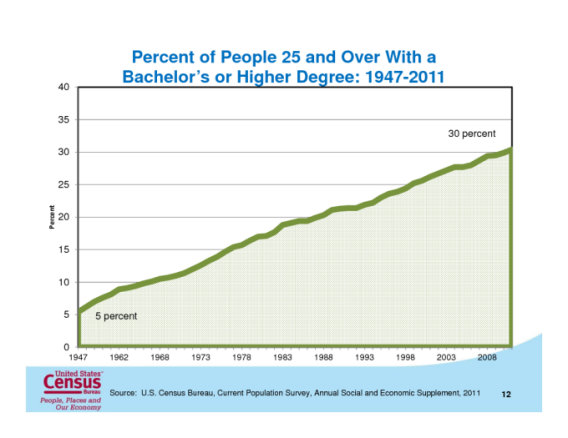

Yglesias says “Colleges charge much higher prices today than they did 40 years ago but many more people have college degrees” and backs this up with the following graph

What’s wrong with this picture?

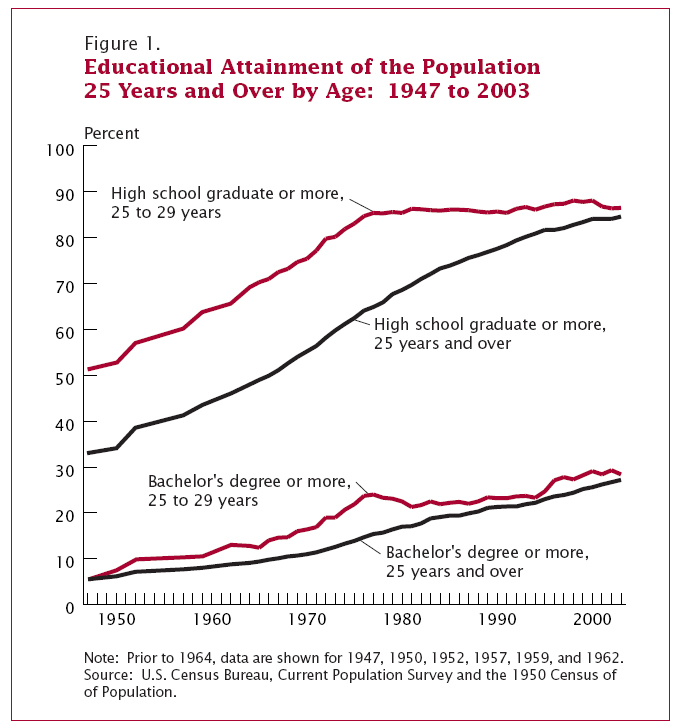

Yglesias is looking at the proportion of the entire population who have a college education. The graph begins in 1947, when the oldest members of the population would have had their education in the second half of the 19th century. At the end of the period, we’re looking at people educated in the second half of the 20th. It’s no surprise that we observe a steady rise over that period. But, for the question he wants to answer what matters is the proportion of young people currently getting an education. A quick visit to Wikipedia produces a graph that tells the whole story.

Educational attainment for young people levelled out in the 1970s, and has grown only modestly since the 1990s, but the proportion of people with a college education kept growing rapidly, as young cohorts replaced those educated in the mid-20th century and earlier.

In addition to the declining share of high-grade institutions, and class bias in admissions, it’s worth recalling that, in the mid-20th century, it was possible, and widely seen as desirable, for a family to enjoy a middle-class (in fact, upper middle class) lifestyle with a single (male) earner. College participation rates for women were correspondingly lower than for men. Women’s graduation rates have exceeded those for men since the mid-1990s and (in the same process as in the graph above) this has now been reflected in the fact that more working women than men have college degrees. That’s positive in many ways, but it means that fewer young couples can meet the new middle-class threshold of two degrees today than could satisfy the 20th century requirement for one partner (normally the husband) to have a degree.

All of this is predictable enough, given stagnant incomes and rising tuition. Equally predictable is the lame rightwing talking point that consumption of items that have become cheaper, such as household appliances, has increased.

Update Coincidentally, just after posting I found this NY Times story about plummeting applications, and falling admissions, to law school. An extreme case, but an important one, given the historical role of the law degree as a passport to the (upper) middle class.

fn1. Something similar has happened at the high school level where the apparent constancy conceals an increased share of, largely useless, GED certificates.

{ 169 comments }

Bloix 01.31.13 at 4:21 am

Yglesias’ “quality control” has always been god-awful, from his spelling to his ignorance of basic geography. He’s a very, very bright young guy who reads voraciously and synthesizes all sorts of material, but he has little or no experience of the world and he doesn’t know when he doesn’t know. He’s the son of wealthy parents who attended private school in New York and then went off to Harvard; he’s never held a job (other than blogging), and for most of the stuff he writes about – anything to do with money, stastistics, politics, or public policy – he’s pretty much self-taught (he majored in philosophy). So he often writes interesting things but he’s got no internal compass that can tell him when he’s saying something stupid, which is frequently when he’s writing about people whose life experiences are different from his own.

Matt 01.31.13 at 4:26 am

Women’s graduation rates have exceeded those for men since the mid-1990s and (in the same process as in the graph above) this has now been reflected in the fact that more working women than men have college degrees. That’s positive in many ways, but combined with constant aggregate graduation rates, it implies that the graduation rate for men has fallen sharply since the 1970s.

Wait, is it true that graduation rates remained constant? The diagram on Wikipedia shows a local peak at ~1976 for the 25-29 age group, but it looks like that peak was surpassed in the mid 1990s and continued to rise afterward. There’s a newer version of that Census Bureau report here that shows the upward trend continued in following years: Educational Attainment in the United States: 2009

Unfortunately it lacks numerical tables corresponding to that diagram, but it appears to me that bachelor’s degrees in the 25-29 age range went from about 24% at the 1976 peak to about 31% in the most recent year. Or an overall growth of about 29% in university graduation rates in the 25-29 age range. Drawing a straight line between 1976 and the end of the graph, then trying to overlay different parts of the data… it looks like this is about the same growth rate of educational attainment as seen in the census data from about 1953 to 1966. It looks like the fastest growth in attainment rates was actually between the late 1960s and the mid 1970s.

Marc 01.31.13 at 4:31 am

Another chestnut is the idea that medical progress, and technology, must automatically be associated with whatever the person is supporting. So it’s no big deal that incomes have stagnated because…we have computers!

The idea that, perhaps, we could have computers and a more equitable economic system doesn’t compute. Or, more precisely, they don’t want it to.

purple 01.31.13 at 4:34 am

He’s another spoiled twit who wants humble and ignorant servants to attend to him.

No one should go to college and major in ‘useless’ subjects except for people like him.

John Quiggin 01.31.13 at 4:57 am

@Matt I agree that the post overstated the stagnation in attainment. I’ve rewritten it a bit in the light of your comments. And of course, I should pay special attention to quality control when I’m criticising others.

Bruce Wilder 01.31.13 at 5:02 am

The GED goes to college:

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323301104578255992379228564.html

I’m sure it is a huge gain in efficieny, to skip the whole expensive, educational effort, and go directly to the sale of the credential — on-line!

js. 01.31.13 at 5:29 am

Easily the worst part (and I don’t mean what purple seems to be saying at 4). Moving along…

I don’t really get this:

I’m quite inclined to think that you, JQ, are right. Except that the quoted bit would suggest that the answer to the question posed in the title is very much: Yes. No? What am I missing?

John Quiggin 01.31.13 at 5:50 am

@js It’s the difference between a stock and a flow. If you look at the data for the early 1980s, for example, the proportion of 25-29 year olds with a college degree was lower than in the 1970s, so, in some sense the availability/affordability of college education was declining. But the proportion with degrees was still much higher than that of the people the people they were replacing in the population – typically aged around 75, whose potential college years would have been in the 1930s. So Yglesias’ graph keeps on rising steadily

Chaz 01.31.13 at 6:37 am

It seemed like you were really trying to be diplomatic, no matter what, and pulling it off too! And then you say that bit about a net benefit . . .

Made me smile.

YankeeFrank 01.31.13 at 8:50 am

Yglesias’ main job, like most of the MSM, is to place a pretty veneer over the decline of standards of living, quality of life, health, economic and job security, and quality of education of the vast majority of American citizens. We all know what is really going on, except for those who benefit from the current system, who pretend everything is dandy. Rising number of degrees? Appliance sales increasing? Everyone has a smartphone! These “indicators” mean nothing and basically amount to “look, over there!” type “analysis”. That is Yglesias’ job, whether he knows it or not is irrelevant. He’s the man for his time and place.

Tim Worstall 01.31.13 at 9:40 am

“in the mid-20th century, it was possible, and widely seen as desirable, for a family to enjoy a middle-class lifestyle with a single (male) earner. ”

You can do that right now. Of course, it would be a 1950’s middle class lifestyle you would be living.

“but it means that fewer young couples can meet the new middle-class threshold of two degrees today”

Which is one of the reasons (one of mind) for increasing inequality in household incomes. The rise of the two professional income family.

reason 01.31.13 at 10:04 am

Tim Worstall @10

” Of course, it would be a 1950′s middle class lifestyle you would be living.”

NO it wouldn’t. Relative prices have changed enormously, not just the price level!

John Quiggin 01.31.13 at 10:23 am

@Tim @Reason In particular, you couldn’t afford to send your kids to the college you went to.

Matt 01.31.13 at 11:25 am

It’s an interesting what-if: how much income does it take to provide material circumstances like the middle strata of 1950s America? Is it realistic to attain that with a single male earner today?

Arguing for the possibility of emulating the 1950s on one income: In the mid 1950s American vehicle ownership per household was 15% lower than today, and vehicle-miles traveled were 66% lower. The average house had only 42% of the size of today’s. A smaller dwelling is cheaper to furnish, light, heat, cool, and clean. The proportion of children going on to higher education was about 2/3 lower. Appliances, furniture, food, telephone service, and electricity are cheaper now than in 1955. The median real wage for a male earner in the USA is about 50% higher in 2011 than in 1955 (though lower than the early 1970s peak).

Arguing against the possibility of emulating the 1950s middle class on one income: gasoline is about 40% more expensive in real terms. Medical care is more expensive, though you’ll find some savings if you reject treatments/diagnostics developed after 1959. I honestly don’t know how much more it costs in real terms for (e.g.) a doctor to look at your tonsils today than in 1955, though I think it has handily outpaced inflation despite no technical refinements. I also don’t know how costs compare for other household utilities (water, sewer, non-electrical heating). You’ll have to save for your own retirement: there’s probably no pension coming your way.

Though there are some unknowns, medical foremost in my mind, it looks plausible that you could live like the middle class of 1955 on just one median male income in 2012. But living like the 1950s means you’ll have to drastically cut home size, distance driven, higher education for children, and advanced medical care.

Matt 01.31.13 at 11:53 am

@John: isn’t it a bit stacking the deck against matching the 1950s to assume that your kids will go to college in the first place? Educational attainment in the 25-29 age range in 1955 looks about 1/3 of what it was in 2011. Education costs have gone up much faster than inflation but you can claw back 2/3 of it if college becomes as rare now as in the 1950s.

Vanya 01.31.13 at 12:19 pm

@Tim@Matt

Another difficulty with living a 1950s American middle class lifestyle – cigarette prices have risen astronomically.

rf 01.31.13 at 12:42 pm

“He’s a very, very bright young guy who reads voraciously and synthesizes all sorts of material, but he has little or no experience of the world and he doesn’t know when he doesn’t knowâ€

He’s a bright man as far as it goes, in that if you met him on the bus he’d be an engaging and interesting conversationalist, though I’m not sure why anyone would seek out his opinion on, well anything; and no amount of digging ditches in his early 20s was going to change that. He was born to be a member of the US academpundocracy class, so that’s what he is. Sin é

On the other hand there’s Izabella Kaminska, who’s pretty much laying out our future in a succession of thoughtful and beautifully written articles. Why anyone would give a rats ass what Matt Yglesias has to say when there’s such an abundance of riches out there to engage with, I have not a notion?

Trader Joe 01.31.13 at 12:52 pm

Further to Matt @14

Modern expenditures for internet and cable TV would also be saved too…the good news, relative to most of the survey period, is that the cost of a mortgage would again be the same.

Further to Tim@11

It would seem to me, albeit lacking data to prove it, that the rise of the dual earner family (of which the dual professional family is the wealthy subset) is a big driver of the rise in community college or ‘degree mill’ educations. There’s broad middle class perception that a college education is a ‘requirement’ for advancement beyond entry-level so getting that ticket punched is viewed as necessary (regardless of cost-benefit sometimes). Perceived disdain for technical/trade school education is also a factor.

The fairly easy availability of loans to families where one or both parents work also make oceans of money available to finance whatever education the student is able to purchase….as noted in the OP, admissions at mid/upper tier universities hasn’t grown nearly as quickly, so these funds find an outlet in what JQ calls “lower-tier” universities.

I was a little unclear – Is the question of the OP whether there are in fact more college grads (the answer seems to be yes relative to pre 1970s, maybe not so much since) or whether even if there are more college grads, many of them come from lower tier universities or are women so that somehow doesn’t count?

Robert Waldmann 01.31.13 at 1:19 pm

I see Matt’s been here himself. The graph does seem to me to mainly show similar trends for 25-29 and all over 25. The exception is the mesterious bulge in graduation corresponding to a surge in enrollment oh roughly from 1965 through 1973 ( enrollment is in September but I’d time the end of the forcing to roughly ( from memory) January 27 1973). The (then) young men who prefered higher education to fighting in Vietnam make it hard to detect underlying trends. The trend looks positive to me.

Also I consider the low enrollment in law school the best news I’ve read, sine I read that the financial services industry was suffering a brain drain.

fill 01.31.13 at 1:27 pm

Its stupid and distracting to compare contemporary US “middle class living standards†to 1950s standards. Especially considering things like the post 70s neoliberal turn and pointless wars we engage in.

Matthew Yglesias 01.31.13 at 1:29 pm

Class bias in admissions: Absolutely. And totally agreed on the Ivy League stuff.

But the question I was trying to get at was, specifically, what is it that the typical American family consumes less of today than 40 years ago to offset the fact that people clearly have bigger houses and more gadgets. The obvious candidates are health care and college education, the relative prices of which have seen dramatic increases over the past four decades. But reading this chart it seems clear that consumption of college education has not declined, despite the fact that the early seventies seemed to experience a “Vietnam bump” in college enrollment.

That observation’s not meant as a whitewash of the US education system. Clearly high school graduation rates have stagnated, funding streams are upside down, elite institutions are educating a smaller and more upper class set of kids, etc., etc., etc.

Harald Korneliussen 01.31.13 at 1:40 pm

Wouldn’t getting access to the housing market – even 42% smaller dwellings on average – be pretty impossible today on one man’s 1950 income?

Matthew Yglesias 01.31.13 at 1:48 pm

Incidentally, I’d sort of like John Q. to explain what it is about the disagreement here that merits so much snark and condescension in response.

My claim was: “Colleges charge much higher prices today than they did 40 years ago but many more people have college degrees.” The point was illustrated with a chart.

John Q. prefers a different chart and reaches the conclusion: “Educational attainment for young people levelled out in the 1970s, and has grown only modestly since the 1990s.”

Unless I’m missing something, that means John Q. and I agree that more people are going to college despite the higher prices. Right?

David 01.31.13 at 1:52 pm

Echoing others above: the avoid-the-draft bulge in college attendence obscures a much longer-term increase in college attendence. Without that bulge, bacjelors degrees were at 10 percent somewhere in the 1960s, go to 20 percent in the 1980s, and are now approaching 30 percent.

The leveling off of the high-school graduation line is a little misleading. It would have had to level off no matter what as it approached 100 percent.

shah8 01.31.13 at 1:56 pm

Isn’t it easier to say two things about this?

1) We live in a bigger, more well capitalized place. No shit refrigerators are cheaper to buy. More customers, paid for infrastructure (public and private), and deep wells of experience. Middle class standards have also been lifted by belonging to better, wealthier, networks and generational transfers.

2) Isn’t the crisis about the cojoined issues about debt and opportunity rather than scarcity? Anyways, flat out, if the gini coefficient is rising in the US, then by definition, the middle classes are shrinking. So there cannot be a question about what is happening, but about why, and I think Yglesias’ point is simply about increasing clarity on the relative complexity of the topic. This murkiness is definitely aided by definitional ambiguity about what is middle class. I suggest that what’s good for the banker is good for the consumer, and that we probably should consider that people who are middle class members of good standing can easily survive a “stress test”. So, instead of salaries, with all of it’s interrelationships with location and benefits, why don’t we define “middle class” as having a reasonably liquid wealth of $50,000? Even $10000? Now look at this link… http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2012/06/12/chart-of-the-day-median-net-worth-1962-2010/

rf: Izabella Kaminska makes me rant in my head with jeremiad blog screeds when she blogs about post-money/post scarcity. In their way, her works are interesting, but terribly autistic…

I mean seriously though, if y’all would just think about it for a second, the middle class isn’t dying for a lack of goods and services. It’s dying from a surfeit of risk that kept getting shoveled on, away from the elites of various stripes, many of whom’s normal job is to bear those risks. Many Chinese people look back fondly on the days of the 80s and 90s, even though they had nothing? Why? People had firm places to stay, firm job to work at, even though both were shit. Today, a place to stay (where the jobs are) is expensive to rent or buy, and a hundred underemployed engineers scramble for one dignified public sanitation job. No apartment? No sweet honey, and a deep sense of failure for so.

Of course, one realizes that this is inherently a pre-revolutionary state of being. Only a jubilee can save us all.

rf 01.31.13 at 1:59 pm

” Izabella Kaminska makes me rant in my head with jeremiad blog screeds when she blogs about post-money/post scarcity. In their way, her works are interesting, but terribly autistic…”

I’m a dilettante on most matters, so you might well be right..

fill 01.31.13 at 2:00 pm

I think the issue is less about number of degrees and more about standard of living. Standard of living is the kicker in this increasingly credit based financial economy with a decline in manufacturing based jobs and an increase in service oriented jobs that you probably don’t need a degree for. I have a degree that I bought (cough, earned, cough) in the past few years. I’d happily sell it anyone… and buyers interested?

Lurker 01.31.13 at 2:02 pm

I’d like to argue against Matt on one very important point: discarding the higher education because “proportion of children going to higher education was 2/3 lower” is not a valid methodological choice.

If we are thinking about a family with the parents in their early thirties, late twenties in 1950’s, the children are going to college in 1960s or 1070s. (Oh yes, the boys are going to avoid the draft that way.) And due to low in-state tuition rates, any middle class family with a single earner has a possibility of putting the children to a good college, if they are merited enough. And if they are not, there are plenty of good blue collar jobs available. So, the standard of living is much higher in that regard.

Today, even clear merit-based scholarships would be difficult for a kid from a family with a single earner and a stay-home parent to get. With an intact family, there is no clearly demonstrated hardship. And getting extracurricular merits on the application is often quite expensive.

rvman 01.31.13 at 2:34 pm

The late ’70s peak was a one-off caused by 18-24 year olds who otherwise would have gone into the work force going to college instead to get a draft deferral during Vietnam in the late ’60s to early ’70s. The high school graduation rate has plateaued, but if you take out the draft avoidance effect, Bachelor’s degree rates have been steadily increasing, just as Matt is trying to say. He did pick the wrong data to graph, but in actuality the only difference between the 25 and over data and the 25 -29 yo data is that the latter is noisier, not that the trends are different.

ajay 01.31.13 at 2:37 pm

Izabella Kaminska makes me rant in my head with jeremiad blog screeds when she blogs about post-money/post scarcity. In their way, her works are interesting, but terribly autistic…

Don’t use autistic as an insult.

shah8 01.31.13 at 3:02 pm

I’ve had this discussion on the interblogs before, ajay. I’m really not interested in rehashing it. If the high horse pleases you, then so be it, but I find it so fascinating that you are so willing to be offended for someone else’s benefit. However, I’m not going to be responsive to a cheap bit of policing on a word/word use that people do use from time to time. In case you need the hint, I am not not saying that Kaminska’s arguments behave like autistic people, any more than when I say that I’m deaf to your concerns, I am behaving like a deaf people (oh, even though I am!). Got it? Good, there will be no further feeding.

ajay 01.31.13 at 3:10 pm

If you don’t like being picked up on it every time you do it, then it might be an idea to stop doing it.

Alex 01.31.13 at 3:20 pm

I mean seriously though, if y’all would just think about it for a second, the middle class isn’t dying for a lack of goods and services. It’s dying from a surfeit of risk that kept getting shoveled on, away from the elites of various stripes, many of whom’s normal job is to bear those risks.

sense.

LSTB 01.31.13 at 3:27 pm

[Tried posting this but it vanished into the queue.]

“An extreme case, but an important one, given the historical role of the law degree as a passport to the (upper) middle class.”

What is this an extreme case of?

The perception that law degrees provide a “passport to the (upper) middle class” is precisely why the legal education system over-expanded. The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Outlook Handbook has been predicting surplus numbers of law graduates relative to lawyer jobs for many, many years. Law schools play to this perception by claiming their degrees are “versatile,” but that’s full of holes (esp. post hoc ergo propter hoc rationalizing).

If law school really is an important case, then what does their coming collapse say about the value of the college education necessary to proceed to law school? If the applicants needed to go to law school to join the middle class, it sounds like their college degrees weren’t worth much.

shah8 01.31.13 at 3:30 pm

Oh yes, the “call out”. I’m so scared. You got me! I’ll just limp along, now…

You’re free to do your own google work, you know. Why not google “autistic insult” for starters. Or you could check out the original etymology of the term. Maybe grab a hint that it has a minor life as a technical term in computer science, science fiction, and pop culture. Given that, I feel it’s a better term than, say trying for a prejorative use for platonist.

Anarcissie 01.31.13 at 3:37 pm

In discussing the higher price and consumption of higher educations, one might want to ask about the quality of the product. The primary value of a college education for most people, by their own report, seems to be passage through the class system to a higher level, and a credential permitting one to have a job. But as the proportion of college-educated people in one’s cohort rises, its value as a pass to a higher class position and as a credential must correspondingly decline. In short, the typical working (‘middle’) class young person is getting a much worse deal than his predecessors of previous generations: less product for more money.

Barry 01.31.13 at 5:21 pm

BTW, I’d like to see some support for Matt’s work being generally good (I tend to encounter critiques online, and so probably have a biased view).

As for Matt having to learn a lot of stuff himself – well, he majored in Philosophy, so he doesn’t have any excuses. He should know how to think, how to learn, and how to judge ideas.

genauer 01.31.13 at 5:27 pm

And now for German 2 cents:

Most of you in the Anglo countries might not be that aware, that the Bologna process,

to introduce the Bachelor & Master concept on the continent, means in many cases a reduction of study times of formerly 6 – 7 years for diploma to 3 years for a bachelor.

It is a recognition, that in many cases, the 3 years more studying do not really yield the benefits to outweigh the 3 more years, those guys are working, and paying for the pensions : – )

What we see now, is not only saturation, but slight reduction of the education surge.

As Anarcissie said, in somewhat different words, the signaling value of more university education has disappeared, and we see more of the severe limitations of real improvement of the human capital : – )

With respect to Izabella, to defend Diocletian over the year-end, I thought she would go the way of Baron Münchau(sen), coming up every week with an even wilder gross-out. Fortunately I havent seen that so far.

Matthew Yglesias 01.31.13 at 5:50 pm

Another issue to consider here is that something like 4.5 million currently enrolled college students are over the age of 30 so there are some drawbacks to JQ’s preferred chart.

christian_h 01.31.13 at 5:54 pm

Can I just make a cranky comment about “living a 50-ies middle class lifestyle off one income”? Apart from the issue of home size – something that needs its own careful analysis beyond means or medians (eg, how much of this is McMansions at the upper end of the so-called “middle class”, how much is due to smaller household sizes etc.) – the “trappings” of modern middle class lifestyle are not exactly that – “trappings”. Mobile phones, computers and internet access,… these are not luxury items, they have become virtual necessities, especially if you want to hold one of those “middle class” jobs. The idea that just because a median household, for example, consumes more on some measure than the median household in 1950 did – supposing this is true – the people in that household have higher quality of life is absurd. basing this on the assumption that “needs” have not changed since 1950, so therefore this additional consumption must be a lifestyle improvement is doubly absurd.

MPAVictoria 01.31.13 at 6:11 pm

“Can I just make a cranky comment about “living a 50-ies middle class lifestyle off one incomeâ€? Apart from the issue of home size – something that needs its own careful analysis beyond means or medians (eg, how much of this is McMansions at the upper end of the so-called “middle classâ€, how much is due to smaller household sizes etc.) – the “trappings†of modern middle class lifestyle are not exactly that – “trappingsâ€. Mobile phones, computers and internet access,… these are not luxury items, they have become virtual necessities, especially if you want to hold one of those “middle class†jobs. The idea that just because a median household, for example, consumes more on some measure than the median household in 1950 did – supposing this is true – the people in that household have higher quality of life is absurd. basing this on the assumption that “needs†have not changed since 1950, so therefore this additional consumption must be a lifestyle improvement is doubly absurd.”

Well said.

Gerry 01.31.13 at 6:43 pm

Two things re 50s lifestyle/50s single income:

First, monthly cost of a home/apartment fifty years ago could easily be one week’s pay out of the month. Home size was highly variable — they built “starter homes” back then. Paying off a mortgage in 15 years was common – payments that would be inflation-equivalent to 100 or 200 bucks a month were common too. My folks’ was $10/month and they weren’t special, just thrifty.

Secondly, appliances? Seriously? Can I buy a refrigerator — or anything else — today for any price that will last sixty years? I think if you could somehow quantify the dollar per year of use for a lot of durable goods you would find that this is a serious apples-to-oranges comparison.

Martin James 01.31.13 at 6:53 pm

I’m curious whether JQ think s the middle class numbers should be adjusted for race/ethnicity and immigration. I can see arguments both ways. In other words, education is up for Hispanics and blacks but since the rates are lower than whites, the increasing number of Hispanics is slowing the rate of improvement in educational attainment. However, I can also see the argument that race shouldn’t matter and that its just racism keeping the increasing number of Hispanics from improving on the middle class standards.

I do think it is incorrect however when the lack of rising living standards is phrased as “doing less well than their parents” because the comparisons are not a direct comparison to actual parents and the changing mix is substantial. For example, there is evidence the world over that higher education for females decreases the number of births to those females so there is a force that reduces the percentage of the next generation that is from high education households.

Martin James 01.31.13 at 7:02 pm

Its also curious that an ivy league education of 2013 is seen as roughly equivalent to one of say 30 years ago. Shouldn’t the education be substantially better. Even a 2% annual improvement in the quality of education mean that an ivy league graduate is twice as educated as one from 30 years ago?

One the other hand, if the ivies are not improving each year, why are we using them as a benchmark for anything that matters very much to quality of life?

Benquo 01.31.13 at 7:35 pm

I am going to pile on here and second ajay’s request in 30.

Brian 01.31.13 at 7:42 pm

I’d like to third ajay’s request in 30.

John Quiggin 01.31.13 at 7:55 pm

Lots of (I’m guessing) male commenters have ignored the primary cause of the rapid growth up to the mid-1970s, which was the increase in college attendance by women in the 1960s. If draft deferments for 18-year old men were the main story, the proportion of 25-29 year olds with degrees should have kept rising well after 1976

Alex 01.31.13 at 7:56 pm

Can I buy a refrigerator — or anything else — today for any price that will last sixty years? I think if you could somehow quantify the dollar per year of use for a lot of durable goods you would find that this is a serious apples-to-oranges comparison.

I think you’d find that this is survivorship bias. People imagine that buildings, especially, were better in the Old Days because there are some old buildings around. Of course, you can’t see the ones that fell down, burned down, or more importantly, were knocked down because they no longer suited their purpose.

Further, how much electricity did they use?

Chaz 01.31.13 at 8:10 pm

“Incidentally, I’d sort of like John Q. to explain what it is about the disagreement here that merits so much snark and condescension in response. ”

Well he already did, in the original post. I will simplify it:

Your chart combined with the context you placed it in implies that the proportion of people graduating college each year has increased six-fold in the last sixty years. This is not true or even close to true. Therefore you are a liar.

John has speculated that you did not mean to lie, but rather actually believe that the percentage of Americans graduating each year actually has increased six-fold. In that case, you are not a liar. Instead you are dumb and incompetent at your profession.

You seem to be arguing now that graduation rates have been increasing (true, they have slightly increased), and that’s all you were trying to say, so you were right all along! If so why did you post a figure that was completely inappropriate for the context? This also suggests that you are dumb and incompetent at your profession.

John Quiggin 01.31.13 at 8:11 pm

@Matt Y Apologies for getting snarky, but this is a very important question and, having addressed it at length in the past, I was annoyed to see you give an answer based on an obviously incorrect measure, and one that I regard as wrong on balance. To repeat,

(a) people who got their education 40 years ago are (mostly) part of the population measured in your graph, so this is obviously not the right measure (and if more people are getting education after 29, that tends to support the view that parents are having difficulty paying for college for their children).

(b) given the heterogeneity of US post-secondary education, it’s not sufficient to look at aggregate numbers. Middle-class access to the kinds of institutions we usually talk about in these discussions has declined. If you want to argue that the decline in access to high-level colleges has been more than offset by the expansion of the lower tiers, you should make that explicit.

John Quiggin 01.31.13 at 8:21 pm

Since I have to do the gatekeeping here, I’ll make a policy statement. I do not allow the use of terms like “autistic” as insults, and I assume the same applies to other CT members. Given the discussion that has ensued, I’m not going to delete the original comment, but I will do so in future.

Also, I didn’t intend to encourage personal attacks on Matt Yglesias. I didn’t like this post, but overall I think he makes a very positive contribution to the public debate. So, I’m going to delete any further personal criticisms.

Gerry 01.31.13 at 8:35 pm

@47, I don’t think a survivorship bias can be legitimately applied to durability of consumer goods, or to old buildings, but who am I gonna believe, my lying eyes? As for how much electricity old appliances used, I would say only that it has to be measured in minutes of work needed to pay that fraction of the electric bill.

Survivorship bias may be at work somehow in the OT however, if higher-education relationship to higher life expectancy means non-college-degree individuals tend to exit the population sooner than degree holders of the same age.

Harold 01.31.13 at 8:37 pm

It is not a personal criticism, but Yglesias consistently declines to engage with substantive questions concerning his arguments.

rvman 01.31.13 at 10:15 pm

John @ 47 – good point on women being a component of the rise. The census bureau has the relevant chart broken by gender below:

http://www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/education/data/cps/historical/fig6.jpg

The female line is a slightly noisy but linear trend from the 40s on. The men’s line is mostly linear, except for a big jump in the early 50s (GI Bill) and a bubble-looking peak in the mid-late 70s (Vietnam). The women’s numbers show at most a small echo of the Vietnam era peak – logically, since they weren’t draftable.

Matthew Yglesias 01.31.13 at 10:37 pm

“given the heterogeneity of US post-secondary education, it’s not sufficient to look at aggregate numbers. Middle-class access to the kinds of institutions we usually talk about in these discussions has declined. If you want to argue that the decline in access to high-level colleges has been more than offset by the expansion of the lower tiers, you should make that explicit.”

I don’t want to argue any such thing.

Let me restate the argument: There have been relative price shifts over the past 40 years, such that the typical household clearly consumers more (or better) of certain categories of things that have gotten cheaper. Houses are also bigger than they used to be, on average, in the absence of relative price shifts. So the question I have is to what extent has increased consumption of the goods that have gotten cheaper been offset by decreased consumption of the goods that have gotten more expensive. The obvious candidates for rising relative prices are health care and higher education. My observation is that consumption of higher education has not, in fact, declined.

I happily concede that your chart of attainment among the 25-29 year old cohort gets at this question better than my chart of aggregate attainment. Both both charts show the same thing, namely that consumption of higher education has not declined.

Right? Now as if often the case in life there are a lot of questions to ask about American college education, many of them very good ones raised by you in this post. But none of that changes the fact that notwithstanding the rising relative price of college tuition, the share of Americans going to college has gone up rather than down since 1972. That’s evident on your chart, and it gets clearer when you consider that there’s been a boom in enrollments by older students.

ezra abrams 01.31.13 at 10:57 pm

I agree with MY that OP is snarky and off point

And for all those who seem to think MY is a total looser, you try writing a column or two a week – it is a lot harder then it looks, esp if you work for someone halfway reputable, who checks your facts

ezra abrams 01.31.13 at 11:08 pm

My neighbor gets antique sportscars delivered via covered transport (they have a van and drive the antique into the van, so the antique doesn’t get dirty during transport)

Not far is away is our local supermarket.

late At night, I often see the cashiers walking to the bus stop, to wait half an hour for a bus to the train station, to take them home to wherever it is the poor people who serve my neighbor hood live (i’ve never had the nerve to offer one of these people a lift – only a few minutes in my car }

I don’t give a rat’s fanny about timeseries data or what proportion has or hasn’t gone to school.

the inequality in this country is not right

And something – such as raising marginal rates to 80% and taxing div and cap gains as ordinary income – needs to be done

Another thing is to elimminate the charitable deduction and tax nonprofits as ordinary concerns; far as i can see, the tax benefit works mainly to institutions that serve the wealthy.

and if some people – such as drivers of covered vans for antique ferrari’s – loose their jobs, well, I feel sorry for them, but you can’t make an omelet…

Mao Cheng Ji 01.31.13 at 11:11 pm

“Both both charts show the same thing, namely that consumption of higher education has not declined.”

Look, your chart doesn’t show that.

Suppose one decade your population is comprised of 10 old people, 0 of them college graduates, 10 middle-aged people, 5 of them college graduates, and 10 young people, 5 of them college graduates. So, you have 30 people, 10 of them are college graduates, 33.3%.

The next decade the 10 old people die, the 10 middle-aged become old, the 10 young become middle-aged, and 10 adolescents become adults, 3 of them college graduates. So, you still have 30 people, and now 13 of them with a college degree, or 43.4%.

The aggregate attainment is up, but the consumption declined.

shah8 01.31.13 at 11:18 pm

It’s your blog Dr. Quiggen, but I maintain that my use was within norms as a term of art and was the most efficient normed means of expression. I did not insult Kaminska, nor did I insult autistic people.

If someone saying “I’m offended” is all it took for you to ban the word, again, it’s your blog, but if you expect to talk about an Iain Banks’ Culture or a Hannu Rajaniemi novels in some future book event, you might run in trouble. Or Ghost in the Shell. Or certain discussions about gaming engines. Or relevant discussions in narrow areas of A.I. research–I mean, why not google “autism robotics” and see how naturally the discussion flows. You’ll even find it’s use in game theoretical elements of foreign policy papers. There were actual reasons why I’m stiff about this other than simply being a prickly, insensitive clod. I find this sort of call-out merely a handy fauxgressive lèse majesté if no impact is described.

That’s all.

EB 01.31.13 at 11:23 pm

It is just plain discouraging that posters seem to be aiming to shoehorn everyone in the country into the top quintile. That’s a recipe for disaster. Yes, better access for those in the lower quintiles; yes, less favoritism keeping those born there at the top. But let’s be real; we will only get a comfortable society when having an income (or educational background) that is in one of the lower quintiles still affords a person or a family a decent life.

Matt 01.31.13 at 11:23 pm

@Lurker 28: When I made my comparison with 1955 I was picturing a family with kids almost old enough to exit high school. If you picture a family just starting then after-high-school lies 18 years in the future, early 1970s, and it also means comparing nearly two decades of data instead of just one year. It took me long enough to dig up data to my satisfaction on data from the mid 50s.

Also, I’m not Matt Yglesias, just another Matt of no note.

Main Street Muse 01.31.13 at 11:37 pm

“it was possible, and widely seen as desirable, for a family to enjoy a middle-class (in fact, upper middle class) lifestyle with a single (male) earner.”

I’m assuming John Quiggins has not read The Feminine Mystique, in that he seems to be overlooking the fact that women had very very few opportunities to work those middle-class jobs back in the 1950s. Nor did minorities have opportunities for those jobs.

And I’m surprised that he did not mention the GI Bill of Rights (1944) – which was the gateway to education for so many servicemen (my father, a Korean War vet, included).

Today I live in a right-to-work state with one of the highest unemployment rates in the country – North Carolina – and our Governor feels “his” university system should be geared more toward vocational training, answering the needs of the (nearly nonexistent) job creators of the state. It appears he wants to graduate a whole bunch of WalMart greeters rather than people given the opportunity to work on critical thinking skills.

I also want to point out that the top tier Ivies sent a steady river of grads over to Wall Street, so I really question what they are teaching over in those hallowed halls. Certainly how to run sustainable businesses not propped up by the federal government is not something they are addressing. Nor is behaving in an ethical manner in business. And yes, to be sustainable, ethics are essential in business.

I’m a little shocked that Yglesias would say this: “And families aren’t giving up on food, clothing, shelter, entertainment, transportation, or durable goods in order to afford college…” and neglect to mention that people are heading into massive debt to afford college.

College has grown astronomically expensive. The question is not whether college education is expanding, but whether the costs of college are now preventing people from attending at all.

LMM 01.31.13 at 11:46 pm

Matt@14: In most places, people who want to live in relatively safe neighborhoods and to send their children to better school districts *have* to commute farther to work. What’s more, the school districts often have zoning codes that mandate larger houses — and because those areas tend to sprawl more and because both parents have to work, families need to own two cars (or more, if they have teenage children). These aren’t independent choices — and, were it possible, I suspect many families would make different choices.

js. 02.01.13 at 12:33 am

JQ @8:

Right, of course; think I totally misread that sentence, missing the reference to the population as a whole. Anyway, thanks!

MSM @61:

Umm, Mystique was published in early/mid 60’s? And perhaps you’re taking “widely seen as desirable” to mean something it doesn’t. On the other hand, I completely agree with you that it’s flat out bizarre to talk about a rising or steady “consumption” of higher education without taking account of debt levels, esp. when the upshot is supposed to have something to do with affordability.

leederick 02.01.13 at 1:13 am

Look at the appropriate statistics. http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2012/2012001.pdf Page 413

I think JQ’s interpretation of college history is based on common myths. About 40% of bachelors degrees went to women in 1930 and 1940 (not greatly different from how much go to men now). That was was knocked down to 24% in 1950, so the GI Bill looks hugely important – rather than just gender or an economic need for only one educated adult in a household. It doesn’t seem like the main cause in growth was an increase in college attendance by women in the 1960s as JQ mentions, the number of degrees awarded to men and women went up by roughly the same absolute numbers from 1960 t0 about 1974. Women just went from a lower base.

Harold 02.01.13 at 1:18 am

My father in law’s father was a postman in Williamsport, Pa. During the 1930s he was able to send his four children (including girls) to Bucknell University. This would not be the case today on a postman’s salary.

On the other hand, until the 1940s and early fifties, most people left school at 14.

JW Mason 02.01.13 at 1:49 am

the question I have is to what extent has increased consumption of the goods that have gotten cheaper been offset by decreased consumption of the goods that have gotten more expensive. The obvious candidates for rising relative prices are health care and higher education. My observation is that consumption of higher education has not, in fact, declined.

If that’s the question, then why not look at consumption of higher education — that is, the fraction of the population currently enrolled? (Or if, you like, the fraction of income going to higher ed.) Besides John Q.’s (totally correct) reasons that the chart in the Slate piece is misleading, there’s also the fact that attainment of a bachelor’s degree is an outcome of higher education. Higher life expectancy is an important outcome of health care, but nobody, I hope, would try to use life expectancy as a proxy for the quantity of health care being consumed. Which is the equivalent of what Matt Y. is doing here.

If we go to the Digest of Educational Statistics, we see that the fraction of the population enrolled in higher ed rose from less than 1.5 percent in 1950 up to a bit over 5 percent in 1975, then stayed constant around 5-5.5% for the next 20 years. It started rising again at the end of the 90s and reached nearly 7 percent in 2010.

I don’t think this sheds much light on changing living standards one way or another, but it seems like the right measure for the question Matt Y. is asking.

Matt 02.01.13 at 1:54 am

In most places, people who want to live in relatively safe neighborhoods and to send their children to better school districts *have* to commute farther to work. What’s more, the school districts often have zoning codes that mandate larger houses — and because those areas tend to sprawl more and because both parents have to work, families need to own two cars (or more, if they have teenage children). These aren’t independent choices — and, were it possible, I suspect many families would make different choices.

It’s a good point that these choices are highly correlated. In fact many things that have changed since the 1950s are “environmental” and can’t be bought by any individual, like entrees from a menu, because they’re a dynamic effect of what other people are doing.

But I think that this particular example comes close to placing institutionalized segregation in the “benefits” column for the 1950s. In the good old days, government helped you keep your neighborhood clean. Now it won’t and you have to pay more to get away from Those People. Crime and schools are the words today, but when white flight started the school and crime disparities were much smaller — an apparent result rather than cause of many families moving away, and driving far more.

Harold 02.01.13 at 1:56 am

Was the rise from 5 percent to 7 percent accounted for by more women and minorities attending college? Overall population bulge? Or what?

John Quiggin 02.01.13 at 2:09 am

To repeat myself, while the proportion of young people undertaking some kind of post-school ed has continued to increase, the growth has been much more at the bottom end, in non-research state universities, for-profits and community colleges. While tuition cost at these institutions has risen rapidly, it remains very low compared to the research universities and liberal arts colleges that are the focus of most stories on rising tuition costs, and that dominate the public image of “higher education”. Enrolments at these institutions haven’t risen much and are increasingly dominated by the top quintile.

So, the responses of middle class households are what you’d expect when faced with the combination of rising tuition and a growing wage premium for college education – they’ve substituted a cheaper service (but thereby missed out on much of the wage premium).

christian_h 02.01.13 at 3:17 am

Or, to paraphrase what John Q. is saying here: the consumption of that part of higher education that has seen relative price increases has not, in fact, increased. (Also, what JW Mason wrote.)

LFC 02.01.13 at 3:24 am

MSM @62

I also want to point out that the top tier Ivies sent a steady river of grads over to Wall Street, so I really question what they are teaching over in those hallowed halls. Certainly how to run sustainable businesses not propped up by the federal government is not something they are addressing. Nor is behaving in an ethical manner in business.

I don’t think this necessarily follows. The univs. could be teaching ethics and it could be going in one ear and out the other. Also, undergrads can’t major in ‘business’ in these institutions so they aren’t going to get directly ‘vocational’ sorts of courses — i.e. how to run a “sustainable” enterprise. Also there’s a structure-agency issue, for lack of a better shorthand — i.e. someone can be a reasonably ethical person but, if low on the totem pole of a large organization, not have much opportunity to exert influence on the organizational culture. So s/he in effect may have the choice of going along or quitting (loyalty or exit) but not effective protest (voice) [with a hat tip to the late A. Hirschman].

Chaz 02.01.13 at 3:39 am

Matt, if you’re still following the thread, I just saw a smart quote from you on Jon Bernstein’s quote and it made me laugh (http://plainblogaboutpolitics.blogspot.com/2013/01/going-with-their-strength.html). Thank you.

LFC 02.01.13 at 3:45 am

The one aspect of JQ’s argument I am not entirely ready to go on board with is the assertion that “the chance of getting into the upper middle class (top quintile) with a degree from these schools [so-called “lower tier institutions”] is correspondingly lower…” Even if this is true, there still may be a substantial ‘wage premium’ from higher education period, regardless of the type of institution.

Moreover, there are still some (perhaps a diminishing) number of people who go to college mainly for reasons other than to increase their future earning potential. (E.g., they might actually be interested in learning something.) For these students, the key question is not “which institution will get me into the top income quintile?” but, for example: “which institution will broaden my horizons, help me explore/expand my interests and discover what it is I should spend my life doing?” And the answer to the first question may be institution X, whereas the answer to the second question may be institution Y. Put more bluntly, it is possible to get a good education, assuming one wants one, at colleges few people have heard of and which do not necessarily send huge numbers of grads to high-paying sectors of the economy.

nb 02.01.13 at 4:55 am

Yikes … High school graduate or more, 25-29 years … more or less leveling out against the 100% upper bound! Crisis of capitalism folks!

John Quiggin 02.01.13 at 5:32 am

LFC “which institution will broaden my horizons, help me explore/expand my interests and discover what it is I should spend my life doing?â€

But that only reinforces my point. In the 1970s, bright middle class kids could afford liberal arts colleges and similar places that might answer this question. Now that’s a recipe for ruinous debt, so they go to the local state school where the adjunct instructor has a 4-4 load, or, worse to U of Phoenix. I doubt that will meet either of your goals.

And, of course, as the top quintile has pulled away from the rest, and life has become more precarious at the median, let alone below it, the urgency of getting a job-relevant training rather than an education has become even greater.

nb: you might want to read the footnote.

js. 02.01.13 at 6:04 am

Not to disagree with this really, but just in case someone is unaware, and/or gets the wrong impression from this, for-profit colleges like U of Phoenix and EDMC are practically machines built to saddle their students with ruinous debt. Utterly unlike local state schools in that regard (though actually community colleges are probably a comparison class, esp. given that “local state school” encompasses a bizarrely wide range of institutions). A point that I think cannot be hammered home enough.

(Sorry if OT.)

Meredith 02.01.13 at 6:30 am

Coming to this very interesting discussion late. I’ve learned a lot from the comments, even if the discussion goes far beyond what Matt Y’s or JQ’s analyses here (or disagreements) can possibly address. A few thoughts.

JQ:” To repeat myself, while the proportion of young people undertaking some kind of post-school ed has continued to increase, the growth has been much more at the bottom end, in non-research state universities, for-profits and community colleges. While tuition cost at these institutions has risen rapidly, it remains very low compared to the research universities and liberal arts colleges that are the focus of most stories on rising tuition costs, and that dominate the public image of “higher educationâ€. Enrolments at these institutions haven’t risen much and are increasingly dominated by the top quintile.”

Probably an important corrective to popular conceptions. But really, what else is new? Haven’t the research u’s and liberal arts c’s always, mostly, served the children of the already top quintile? At least now, more of that quintile includes people of color (not a minor achievement in the old US of A — also, people of Irish and Italian and Polish and… descent, who, of course, were once thought of by “whites” as people “of color”). And also (among the need-blind or nearly need-blind schools, at least), even more people of the (mostly) urban working class (as opposed to the very early days of admitting sturdy local farmer’s sons who showed promise to become ministers).

The increases in college enrollments at other schools, not least at community colleges, seem to me to reflect the updated version of getting an 8th grade education (my grandparents’ generation) or a high school diploma (my parents’) — and then an apprenticeship in a trade, a good union manufacturing job, maybe a lower level management position. There are likes here, but also many un-likes, turning the comparisons into apples and oranges. To figure out what percentage of people broke through to the top quintile from lower quintiles in the past in contrast to now — I don’t see anything in all that Matt Y or JQ or others cite to help out with that question.

Of great interest to me (I’m getting old and nostalgic, sometimes even cranky) is the discussion here of 1950’s (I was born in 1950) v. today. Yeah, 1950’s refrigerators were terribly inefficient in their use of electricity (not to mention how small they were, especially the freezer section, and really not to mention the time and work of defrosting!). They also lasted, like, almost forever. (We finally had one carted away only a few years ago, even though it still worked.) (And which is why planned obsolescence got invented, y’all.)

How about we try to build a world where refrigerators (e.g.) are both electricity-efficient AND last almost forever? AND the people making the fridges and the people using them all can make decent livings, in a nice little hum together? What would that look like? That would be an amazing exercise in political and social envisioning.

In the service of which envisioning I would note: my grandmothers both had college educations, but neither had sanitary napkins, much less tampons. (They used “rags” instead.) When my mother was a child in the 1920’s, there were more women with Ph.D.’s in the US than there were when I embarked on a Ph.D. in 1968. (Men in college in that “1960’s” era were virtually never there to avoid the draft, btw. Grad school was the draft-avoidance strategy. Get real.) As a child growing up in a solidly middle class household in those “idyllic” 1950’s, I remember lots of parental arguments about money. It was hard, that 1950’s middle class life. I also remember, NOT as a hard part of that era, things like saving the waxed paper linings of cereal boxes, since waxed paper was useful for food storage (Saran wrap was a HUGE luxury). Not out of poverty, or anything close to it. Even my playmate whose wealthy father was VP of the ink company that, e.g., supplied the NYT with ink (he had an 8th grade education), even her family saved those waxed paper linings. Such measures were just life, middle and upper middle class. You just did it.

I’ll stop. What we all need is time for one another, for one another’s company, and appreciation of one another’s work. Of one another’s hopes and dreams.

greg 02.01.13 at 6:57 am

Hmm. The fact that the class of ‘Ivy League Schools’ has apparently not expanded since the 1950’s while the population has what? increased by over 2/3s? suggests a serious failure of social capitalization. There should be a class of schools today just as good as the Ivy League schools of the 50’s, while today’s Ivy’s should be even better than they were then.

If society is instead undercapitalized, then future capitalization, just to maintain today’s standards of living, will become more difficult, and expensive. And this is an expense that seems increasingly to be borne on the back of the worker.

genauer 02.01.13 at 7:37 am

for the Women PhDs in the 1920, 1968, I would like to see some link, statistics, evidence

genauer 02.01.13 at 8:08 am

http://www.aip.org/statistics/trends/reports/EDphysgrad07.pdf

page 9 shows the numbers since 1900

http://ftp.iza.org/dp5367.pdf

female numbers since 1966

the table, very quick and dirty

so it has even more the time-shift problem John Quiggin is lamented about,

but it shows the same trend, as it should be

lots more until 1970 and then saturating

Mio 50

pop phd ppm of population

1920 106 1081 10 0.05%

1950 151 8376 55 0.28%

1970 203 32094 158 0.79%

2000 281 41998 149 0.75%

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_the_United_States

http://ftp.iza.org/dp5367.pdf

Matt 02.01.13 at 9:42 am

How about we try to build a world where refrigerators (e.g.) are both electricity-efficient AND last almost forever? AND the people making the fridges and the people using them all can make decent livings, in a nice little hum together? What would that look like? That would be an amazing exercise in political and social envisioning.

I think the bolded part is already here, mostly, but out of sight. You can still buy a vacuum cleaner that will last many decades, if you’re willing to pay the inflation-adjusted price from the 1950s. Most of the consumer market has moved to lower costs in real terms. The same goes for carpet cleaners, washers, refrigerators, mixers, ovens, coffee makers, and so on. The stuff that is built to endure with rough use is multiple times as expensive as what you’ll find promoted to the general public. It is a smaller market of higher-cost equipment built for use by restaurants, cleaning services, laboratories, and the like. A lot of it is still built by decently paid labor in Europe, Japan, even the United States. But in the mass market “70% cheaper” or “new features” generally wins over “lasts 50 years.” The same goes even for long investments like housing: you could build a home with planned endurance of 250 years, but it would cost more now and the benefits would mostly accrue after your lifetime.

How do you get people to optimize for the long run instead of the next month, next quarter, next four years? This is the big investment challenge for non-fossil energy sources, too. Operating expenses for non-fossil energy sources are usually lower than for fossil energy, but capital expenses are greater. You have to pay up front but only enjoy a net benefit after years have passed. See also: getting people to commit to GHG emissions mitigation. Or infrastructure improvements. Or fishery stocks recovery. Or pure research. Or groundwater use management.

dax 02.01.13 at 10:06 am

“So the question I have is to what extent has increased consumption of the goods that have gotten cheaper been offset by decreased consumption of the goods that have gotten more expensive. ”

I’m afraid I don’t understand what this argument shows. Debt has been increasing among the middle-class, and debt has been increasing especially among young adults. Just looking at consumption or the asset side of the balance sheet is missing the whole picture; debt has exploded, which means future consumption will need to come down.

dax 02.01.13 at 10:09 am

… Just to be clear, future consumption of debtors (those in the middle-class) will need to come down, while future consumption of asset holders (aka the rich) will go up.

Lurker 02.01.13 at 10:31 am

Please tell me more. When reading this statement, I feel like I’m from Mars. I am a Finn. Here, 15 years’ mortgage pay-off time is common, although older folks consider it altogether too long. Monthly payment (for pay-off, not for interest) is usually, in upper middle class, clearly over 500 euros, sometimes more than 1000 euros. So are you really saying that 200 bucks per month is a lot?

genauer 02.01.13 at 10:58 am

@ lurker

The US deflator from 1951 to 2010 is 36 to 768, or 21. (Reinhart-Rogoff Data)

So a mortgage of 100 then would be 2100 today.

After WWII the UAW (US Auto Union) controlled briefly over 80 % of world car production. Then went on strike for 4 months in 1946 to get some dream pay raise.

To work there, without finishing high school, made you automatically upper middle class.

Nice times, yes, they just didnt last. Today the UAW “controls” maybe some 5% , probably less, of world car production, and has to compete with chinese workers in Volkswagen factories in China.

And I agree with pretty much of what Matt says.

Random Lurker 02.01.13 at 12:23 pm

@dax 84

“… Just to be clear, future consumption of debtors (those in the middle-class) will need to come down, while future consumption of asset holders (aka the rich) will go up.”

Since the assets of the asset holders are mostly the debt of the debt holders seen from the other side, if the debtors stop to have debts the assets disappear, hence consumption for asset holders goes up relative to assets even if it stays flat in absolute terms.

Also, since debts are nominal stuff while “consumption” refers to real (material) stuff, consumption of debtors could stay the same and debt go down depending on what happens to inflation, wages etc.

E.g.: if wages rise a lot in nominal terms, and this causes inflation and the cost of stuff also rise as the wages, real consumption stays the same for both debtors and creditors, but asset holders (creditors) look to spend more relative to their assets that became smaller.

genauer 02.01.13 at 12:37 pm

my apologies.

The data above were for the UK.

For the US it is 4.3 to 38.8, or factor 9.0

Trader Joe 02.01.13 at 12:51 pm

Dax @83 has reconciled JQ and Matt Y nicely.

Wealthier folks, who can afford the more expensive upper tier universities are continuing to consume them as they always have. The middle class, which cannot afford these schools either borrows to go to them (i.e delaying future consumption for eductation now) or they go to “degree mill”/lower tier schools which they can more readily afford (or also borrow to afford) but which likely don’t result in the future income improvement necessary to justify the cost.

The numbers don’t argue for a meaningful change in attendance. Matt Y says he was trying to examine how people afford to pay for a good that has seen costs rise faster than income – the answer is they buy it anyway and use debt (which wasn’t unheard of in the 1950s-1960s, but surely exploded in the 1990s as a means of funding education purchases).

Not necessarily something to advocate – but sorta the American way to buy now and figure out how to pay later. With student loan charge offs at record levels and 1/3 of student loans in default – many are apparently not paying the full inflated price anyway.

mdc 02.01.13 at 1:51 pm

“increasingly dominated by the top quintile.”

Since the recession, many liberal arts colleges have seen their ‘full-pay’ population collapse, which causes the tuition sticker price to rise even as net tuition sinks. This is sustainable if you have a huge endowment. I don’t know where the wealthier are going, but some places are surely less “top-quintile” dominated than they were a decade ago.

mdc 02.01.13 at 1:53 pm

Ps: “less dominated” in terms of student population. In terms of beholden to the ruling class donors who run their boards, more dominated.

ezra abrams 02.01.13 at 3:07 pm

matt @82

there is a problem with your argument – why wern’t the same forces at work in 1950 ?

It could be that they were, and survivorship bias + memory faults have left us with the impression that stuff was better back then

An alternate theory that i like is that the availability of CAD software and CNC and injection molding, etc, has allowed builders to make new versions faster – the rate of introduction of useless minor changes is greatly accelerated by software like Solidworks (that economists don’t know about solidworks always amazes me) and CNC machines that can cut a hard steel tool (mold) for plastic molding..

other theories:

repairmen are more exspensive, relatively, so people dont repair stuff

new construction methods and electronic parts are harder to fix

drive for increased margin at manufacturers has led to cheaper stuff

free market doesn’t work: in the Galbraithian de facto monopoly of the 1950s, manfacturerrs had incentives to build good; in a free market, as we have now, there is only incntive for this quarter

LFC 02.01.13 at 3:16 pm

A few things:

1) Meredith @78:

To figure out what percentage of people broke through to the top quintile from lower quintiles in the past in contrast to now

There is evidence that economic (or socioeconomic) mobility in the US has been declining. See e.g. Lane Kenworthy’s recent piece in Foreign Affairs which summarizes some of the evidence.

2) JQ @76 urges me to read the article he links in the fn of the OP. I have looked at opening graphs and will read the rest. Minor point: not sure why Natl Center for Ed. Statistics measures h.s. grad. ratios against the 17 yr old population rather than 18 yr old (or perhaps they shd do two measures since my impression is that large #s of people graduate h.s. at 17 and at 18, depending on what part of the yr they were born in).

3) I saw some wks ago an article in WaPo saying that several expensive liberal arts colleges had decided to freeze tuition for the coming year. (But didn’t save the link – sorry.) Doesn’t contradict, of course, the main pt about rising trends in tuition — just an interesting data pt.

Watson Ladd 02.01.13 at 4:53 pm

The Ivy League is not the 10 best schools in the US: some of its members are top tier research universities, while others are small colleges. Also, sticker price is used as a form of price discrimination: colleges use financial aid to extract maximal revenue, by adapting the cost to the income of those paying. You need to look at the financial aid policies to determine how expensive a top school is, and the answer is usually not as bad as one would think.

As for the question of educational quality, I would like to note that signalling vs. human capital models of education is a large and ongoing debate. If human capital is the right explanation, then yes we have a problem in not investing enough. If signalling is the explanation, then the quality increase (the signal strength increase) of a Harvard education can’t be made up for by Podunk becoming better in educational terms.

Anarcissie 02.01.13 at 4:58 pm

When I went to college in the late 1950s (one of those highly prestigious eastern universities) the primary concerns my peers expressed with respect to their educations were entry to a higher class position and preliminary job training. One might add ‘meeting the right people’ which applies to both, especially the former. (‘Broadening one’s horizons’ could be achieved far less expensively and more entertainingly than by going to school, but one’s parents wouldn’t pay for it.) I am guessing, without a lot of evidence, that things haven’t changed much. If so, the broader participation of young people in higher education should be seen, not as an increment to their standard of living, but a decay of it, because class position is at best a zero-sum game — everyone cannot be upper-class — and because college degrees have declining power to guarantee employment and income. The consumers of higher education are working harder and going into debt more, and getting less in return, although its outlines may be inflated. I don’t think the provision of cleverer toys like smartphones can really compensate for this fundamental decline in living standards. Anyway, as someone above pointed out, once widely used they simply become part of the work machine.

JW Mason 02.01.13 at 5:12 pm

In the 1970s, bright middle class kids could afford liberal arts colleges and similar places that might answer this question. Now that’s a recipe for ruinous debt, so they go to the local state school where the adjunct instructor has a 4-4 load or, worse to U of Phoenix.

It’s really misleading to lump together of lower-tier public institutions and things like Phoenix. And it’s also wrong to dismiss, as John Q. does, the idea that lower-iter pubic schools can “broaden my horizons, help me explore/expand my interests and discover what it is I should spend my life doing?â€

It is also simply false to suggest, as John Q. does, that the majority of teaching at non-elite schools is done by adjuncts. In general, they are staffed mostly by full-time, tenure-track faculty — including some of the best, smartest, most dedicated teachers I know. As I’ve pointed out before, your co-blogger Corey Robin teaches at one of these non-elite schools. Do you really think Corey is incapable of broadening his students’ horizons, John? Really?

The argument that only the “best” colleges count as higher ed risks coming across as snobbish. It also is a bit circular, since by definition only a few schools can be the “best” by whatever criteria. I suspect it’s precisely the fact that there is a fixed number of spaces at Harvard that creates the demand for it, as opposed to the – relatively minor, in the scheme of things — substantive difference between the education available there vs. across town at UMass-Boston. So it’s not that we’ve failed to expand the supply of good-quality higher ed — John Q. is grossly undervaluing nonselective public institutions. It is, rather, than in a society where class and status hierarchies are steepening for other reasons, college students and their families place increasing value on exclusivity as such.

js. 02.01.13 at 5:27 pm

JWM @96:

I agree with everything you say, but JQ’s quoted sentence is a fair bit closer to being true if you replace “local state school” with “local community college”. Still, not completely true because: (a) the cost of taking classes at a community college and the cost of taking classes at Phoenix etc. are in different orders of magnitude (as I noted above); and (b) there are at least some tenured/tenure track positions at community colleges (at least I think this is generally true). Still, it makes a lot more sense on this reading.

lt 02.01.13 at 5:40 pm

Um, yeah, js, there are a lot more than “some” tenure-track profs. at community colleges. My department alone has about 60. And we’re for the most part we’re not serving students who once would have been able to go to elite liberal arts schools, we’re serving students who wouldn’t have had the opportunity to go to college then.

BTW, adjuncts can’t have a 4-4 teaching load at a single school – then they wouldn’t be adjuncts. It’s true that a lot of full timers at C-Cs have 4-4 loads. On the other hand, we’re less likely than Ivy League profs. to resent our teaching as a distraction from our real research, and we’re extremely unlikely to pawn them off on our TAs, since we don’t have any. And yes, I think I’m perfectly capable of widening their horizons. I’ve had students from our major go on to those very competitive elite schools and graduate school – to the extent that the inequality at those places isn’t even worse than it is, some of it is because of the work we do to give non-rich or even non-middle class students a path to get there.

JW Mason 02.01.13 at 5:52 pm

JQ’s quoted sentence is a fair bit closer to being true if you replace “local state school†with “local community collegeâ€.

Nope, still just as wrong. As lt says.

Martin Bento 02.01.13 at 7:05 pm

In evaluating how much higher education people are now purchasing, we should look at the value they are purchasing, not the piece of paper (a nominal measure of value) or the time to obtain it (which should be counted as cost, actually, not value). To a large degree, especially since we are looking at bottom-line economic value here, higher education is a positional good. The total quantity of a positional good in society cannot increase. Therefore, to the extent people are paying more for college, multiplied by the extent that they are “getting more of it” – meaning expending more time in its pursuit, they are paying more for, on net, the same value. There is, of course, a lot of value to higher education beyond the positional, but the “wage premiun” to higher education is positional and cannot increase in aggregate. People are not and cannot in aggregate “buy more” positional education value – they are just, in aggregate, paying more to try to gain at the expense of others.

John Quiggin 02.01.13 at 7:24 pm

@JWM That’s a fair point, and my comment was too broad-brush. To backtrack/clarify a bit.

1. I didn’t mean to “lump in” state schools and community colleges with U of Phoenix and its for-profits imitators, – I did after all say, “or worse”. But, for profits do give degrees, so they are part of the expansion in numbers

2. There’s a lot of heterogeneity. While some state schools and community colleges are excellent, others are not. And similarly as regards outcomes. For students who can use community college as a path to a four-year degree, it’s a huge benefit. But there’s also a high dropout rate, reflecting both the family circumstances of the students and the limited resources of these institutions.