After finishing Shadow Of A Mouse, I turned to the next title on the pile: E. H. Gombrich, The Depiction of Cast Shadows In Western Art [amazon].

It comes with its own mouse that comes with a shadow!

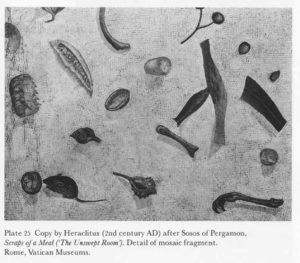

Furthermore, I find that someone has made an animation, “The Unswept Floor”. So that completes the circle.

The Gombrich is definitely your first pick if you are looking for a quick introduction to the topic of the depiction of cast shadows in Western Art – since it’s your only pick. Next up: this thicker treatment [amazon].

Gombrich’s starting point is the observation that, although modeling (shading to provide volume) is a technique that, once picked up, is never really dropped, shadows come and go (as befits their nature.) They come into, and go out of, artistic fashiion. Leonardo studies them intensively but advises against their depiction on the grounds that they are compositionally disruptive and distracting. Caravaggio gives us lots of shadows. That line leads to Rembrandt.

Honestly, the interest of this little book is thinking to yourself: I have no idea which of my favorite artists paint shadows and which avoid them, come to think of it. Well, it’s kind of fun to look and see.

I mentioned in my previous post that the development of shadows in Disney animation functioned to break down the two plane division between ‘cel space’ – i.e. the top level where characters move – and backgrounds. This division is a function of the technical division of labor between animators and background painters, of course. It produces a generally flat impression, hence a shallow space, but that’s not the problem. In fact, it’s almost the opposite of the problem. If Mickey only ever stood against mountains in the far distance, background painting would about do it. The problem is that in closer quarters, it’s tougher to integrate what ought to be shifting depth cues.

Using a sixteenth-century painting as a model, [Don] Graham described its pictorial space as “like a little stage, which is referred to as the picture box. As we shall see the picture box takes many forms and its use is constantly changing. In its classic form it represents a small stage usually viewed from normal standing eye level and easily encompassed by the eye. The distance separating objects on this stage can easily be suggested graphically.” One may envision the animators arraying their toon figures in such an imaginary vaudeville setting. He urged his animators to estimate with great accuracy the volume of “floor space” that each object and action would require. “The only limit we must impose,” he wrote, “is that the little stage be confined to shallow depth and a reasonable dimension from side to side or top to bottom.” This shallow “picture box” built around acting figures was precisely the space that Graham was trying to get the animators to master. (156)

Shadows are not the only tool for mastering this, but they are very helpful for bridging that gap between cel and background.

Here are two works Gombrich mentions which perform this picture box trick in ways I am sure I never would have noticed. First, Portrait of Alexander Mornauer

And Hans Holbein, Christina of Denmark:

Do you see it?

Both the German Master of the Mornauer Portrait (Plate 22) and Hans Holbein (Plate 23) placed the model in full frontal light and allowed their shadows and that of the frame to be visible on the wall behind them. We may not necessarily notice these vague shapes, but they still add to the sense of presence of the sitters. (33)

It’s painting the shadow of the frame that really does it. It’s what really generates that quadratura illusion that the picture space is an extension of the viewer’s space.

Interestingly, it looks like the Mornauer omitted the frame shadow before a very recent (1991) restoration. Funny. It didn’t occur to whoever did the last restoration to paint the shadow of the frame.

{ 24 comments }

ph 11.25.17 at 8:27 am

Thanks for these. 96 pages for 20 bucks seems very steep to me. Perhaps some used copies may be better value.

As good as Gombrich can be, I prefer Panofsky. His Perspective as Sympbolic Form is a classic should one wish to read one. It’s tight, focused and features very useful notes. Michael Baxandall’s scholarship puts him almost in the same class, but his prose can be dry. His Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy is a well-grounded introduction to painting of that day, not on par with Thomas Crow’s Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth-Century France, but still good. The writings of Joshua Reynolds are a bit stuffy, but open a very clear window on the aesthetics of the late 18th century, and are available to the interested.

For extremely readable solid historical scholarship and incisive art criticism from modern authors, some favorites include:

Madame Pompadour: Images of a Mistress, by Colin Jones.

David (Jacques-Louis), by Simon Lee.

The French Revolution as Blasphemy: Johan Zoffany’s Paintings of the Massacre at Paris, August 10, 1792. by William Pressly.

All of which are available right now for half the money Amazon wants. The Jones and Lee are almost essential. There are several other excellent studies of Zoffany/Zoffani, but these tend to be larger and more expensive. Pressly focuses on several key works and their life as reproductions.

John Holbo 11.25.17 at 8:33 am

I am availing myself of the library option myself. But glad you are interested, ph. I hope I am not driving off the CT readership generally with these odd angle art posts.

Adam Roberts 11.25.17 at 9:02 am

You’re not driving me away: I think this is fascinating. I’d literally never heard that Leonardo advised against painting shadows, or that some artists did and some didn’t. And the shadow implicitly cast by the frame is an extremely cool thing, simultaneously realistic and breaking-the-fourth-wall meta.

On animation, I read somewhere that the representational nut the Disney artists found toughest to crack was realistic-looking water. The water in the whale scene in Pinocchio is all frilly and odd-looking; the water in the sorcerer’s apprentice sequence in Fantasia is more scrupulously animated, but looks too gluey and sluggish on screen. Jungle Book is the first Disney movie that really gets water to look right. Maybe there’s a similar upward trajectory for shadows in Disney.

kidneystones 11.25.17 at 9:12 am

Hi John, the posts may appeal to readers unprepared to join the discussion. I’m interested and grateful. The art and culture are indistinguishable from the politics and social issues Corey discusses, and provide visual, material evidence of interest. The political woodcuts of the English civil war period are invaluable to our understanding of the forces at work.

Imagine trying to understand the politics of the present in a cultural vacuum.

Who doesn’t want to see the pictures? I hope others either jump in, or try some of the recommendations. Thx.

bob mcmanus 11.25.17 at 9:55 am

“Were the shadows to be banished from its corners, the alcove would in that instant revert to mere void.” Junichiro Tanizaki, 1933

A tokonoma is always at the side of a wall instead of the center, in order to take advantage of indirect lighting.

John Holbo 11.25.17 at 10:34 am

“I’d literally never heard that Leonardo advised against painting shadows, or that some artists did and some didn’t.”

Apparently Leonardo wrote 70 pages on how to do and concluded: don’t try this at home, kids!

Dwight L. Cramer 11.25.17 at 3:05 pm

Assuming that your interests encompass drawing, as well as understanding the social phenomena of animation and its impact on the culture, high and low, I’ll offer the following observation from a guy named Robert Beverly Hale, lecturing back in the 1970s–‘beginners are infatuated with cast shadow, they love it like they love their mothers, or their lovers. They want them everywhere. You must learn to control them, lest they control you. You must learn to control them, like you learned to control your mother–or your lover’ (laughter). That’s in quotes but it’s a quote from memory. Hale was lecturing on anatomy and warning his listeners that cast shadow (as well as creating the illusion of depth can, depending on how it falls, destroy the illusion of form).

Leonardo’s observation is one of many. Panofsky’s stuff (recommended above) is incredibly rich, though the volume mentioned is a padded essay, there is a collection of his essays floating around floating around. Some of his personality floats through and he must have been a remarkable man.

These thoughts are offered as a retiree taking drawing and painting lessons at my local community college. Actually, that’s a bit of an understatement, a graduate of perhaps the best art school in the old Soviet Union somehow washed up in the Southern Rockies and is running an atelier under the radar. A little group of us are taking advantage of the situation (for instance, from time to time he offers a course called ‘The Illusion of Space’, or something like that). Anyway, as the Russian would say, ‘five minutes of drawing is worth five hours of philosophizing.’

Anarcissie 11.25.17 at 3:48 pm

Dwight L. Cramer 11.25.17 at 3:05 pm @ 7 —

I have been trying to force shadows into my drawing work. Outside of modeling the figure, they don’t seem very lovable to me. However, one of my atelier colleagues does love them and causes them to spring forward and make comments, so to speak, on the subjects of her drawings. Sometimes cheesy (shadow is a jokey distortion of the figure), sometimes very, um, illuminating. There are shadows and then there are shadows. Anyway, it’s an interesting subject.

ph 11.25.17 at 5:22 pm

@8 Thank you for your comment.

Your ‘padded’ remark prodded my into reviewing the original and the Wood translation which I own. So, I’m doubly grateful. After rereading Wood’s commentary I have to say I disagree on the utility of the notes. Wood does an fine job of contextualizing Panofsky’s observations as they appear in the text, and opens up a variety of avenues for further inquiry. Congratulations on taking up the pencil! Sounds like you have a great teacher.

@5 Thanks for the quote from In Praise of Shadows. I can never completely rid myself of the sense that Tanazaki is pulling our legs half the time. I’ve read the Seidensticker translations of Snow Country, Thousand Cranes, and Decay of the Angel. Seidensticker’s translation of Tanazaki’s Some Prefer Nettles, which I’m sure you know, is a wonderfully dark tale.

bob mcmanus 11.25.17 at 8:02 pm

Tanizaki’s vulgar flaunting of his irony is intended to be a reproach to the refined expression of Soseki and Kawabata, and he was followed by Dazai and Mishima, Oshima and Masumura. Pedantry is fun.

Things glanced at today: several episodes of current anime looking for shadows or their lack; Thomas Lamarre on limited vs full animation; Murakami Takashi (“Army of Mushrooms” without shadows), Azuma Hiroki on Murakami; superflat, hyperflat; Baudrillard; ghosts in the shell (is there? the shadow of a ghost? a spectre?).

Giving a fig about the “illusion of depth” (just another idealism) goes against post-post-modernism/post-structuralism that there only remain surfaces that slide and to slide over; the database is the interface; neither I not my moue is casting any shadow on CT, which is my screen.

Realism is reactionary.

DCA 11.25.17 at 8:13 pm

Lawrence Wright’s book “Perspective in Perspective” has some useful information and comments on sciagraphy in amongst t

DCA 11.25.17 at 8:14 pm

Lawrence Wright’s book “Perspective in Perspective†has some useful information and comments on sciagraphy in amongst much on perspective.

Bill Benzon 11.25.17 at 9:59 pm

@Adam Roberts: FWIW, back in the Pinocchio/Fantasia era Disney had an animator–I forget his name–who did nothing but water. Maybe he finally figured it out by Jungle Book time – though the film, itself, alas, is a bit of a drag. Any Turbulence for Dummies book is likely to have images from Leonardo’s sketchbook where he shows turbulent flow in, guess what? Water.

In the CGI world they deal with both water and shadows in the same way, by simulating the underlying physical process. Richard Friedhoff and I talk about this in our 1989 book, Visualization: The Second Computer Revolution.

Bill Benzon 11.25.17 at 10:05 pm

Oh, concerning shadows in Disney, I have no general observation, but they were central to the sorcerer’s apprentice sequence in Fantasia. For example, when Mickey takes an ax to the broom, we don’t see the deed directly. We only see the shadow. And that’s only one instance of shadows in the sequences. They’re all over the place. The Night on Bald Mountain makes effective use of shadows as well.

John Holbo 11.25.17 at 11:45 pm

Thanks for useful comments. As you may have guessed, I’m trying to write a paper about all this. It’s about Gombrich and illusionism, specifically. Shadows are going to be my case in point.

Alan White 11.26.17 at 12:08 am

Bill (if I may)–I once used the Fantasia sequence in a paper to define the logical opposite of Occam’s Razor–Mickey’s Splinters!

ph 11.26.17 at 1:21 am

@14 my memory of Bambi and the silhouettes of leaping animals against leaping flames is very vivid. Shadows are used for great dramatic effect

@15 Thank you for the reminder re: irony. We’re well into the weeds now so why stop. Re: JH’s wish list, subject matter, the stability of the visual text, and audiences.

We’d need to distinguish between the aesthetic preferences regarding realism (and other dramatic twists in Italian baroque, mannerism, high renaissance, etc.) with the demand for realism in botanical studies, for example, in the latter half of the 18th century. Plant science and categorization mattered and had for some time. Joseph Banks should not be confused with realist painters and engravers of different types of the same and proximal periods. Many modern critics display little awareness of actual 18th and 19th-century opinion on realist representation, and the various objects serving as physical media – objects which include canes, scabbards, blades, fans, watches, watch fobs, snuff boxes, brooches, calling cards, fans, flatware, clasps, buttons, specie, paper money, medals, barometers, furniture, windows, curtains, theater props and costumes, lamps, signboards, wall paper, announcements, government documents, book/magazine/newspaper illustrations, and even paintings, engravings and sculpture.

Strictly speaking – I’d argue that only the Banks category of realism placed the highest value on ‘pure’ or reactionary realism. All others favored a recognizable departure from the ‘real’ of one kind or another in the rendering, a departure that is ideally intentional and the result of thought, experimentation, and refinement; although critics recognized the value of the happy accident, too.

John Holbo 11.26.17 at 1:53 am

Re: the offstage action of that is only represented in shadow, not directly seen, Gombrich has two examples of that.

Gerome’s “Golgotha”

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0d/Jean-L%C3%A9on_G%C3%A9r%C3%B4me_Consummatum_est.jpg/1200px-Jean-L%C3%A9on_G%C3%A9r%C3%B4me_Consummatum_est.jpg

William Collins, “Coming Events”:

http://www.wikigallery.org/paintings/299501-300000/299983/painting1.jpg

ph 11.26.17 at 2:27 am

Sorry, a quick addition. If you enjoy the Hubble images as much as I, then you have some sense of the appetites driving the demand for realism. Banks sailed with Cook to the South Pacific. Zoffani spent a significant period of time in India and here we find a link to Tanazaki and Mishima and even Ishiguro. Zoffani used realism and irony when it served his purposes.

The staging of ‘Les sauvages do la mer Pacifique’ (the Savages of the Pacific ocean’ is an artistic mixture of realism and imagination, of the Banks subject matter, rendered by Dufour in 1804-% as panoramic wall paper. (Spectacular!). Again, wallpaper manufacturing in Europe, like that of high quality ceramics, was driven by a demand for cheaper versions of the much more expensive originals from China and Japan. And then, of course, there’s Blake.

Bill Benzon 11.26.17 at 4:42 am

@Alan White–”Mickey’s Splinters”, love it.

@ph–yes, the shadows in Bambi.

@John–Off screen action in shadow. There’s a scene in the movie version of Revolutionary Girl Utena where Anthy is stabbed off scene, in shadow, and against a red background. That just HAS to be a reference to Disney’s sorcerer’s apprentice sequence. It may also be in the AMV version, but I only know the movie version. For that matter, there’s also the manga, which I also do not know.

Bill Benzon 11.26.17 at 5:01 am

First, I got my terminology mixed up in the previous post. Where I said “AMV” I should just have said TV series. AMV=”Anime Music Video”, which is a different animal entirely. It’s fan-created video using anime clips with sound-track from some (favorite) song.

Now, here’s an AMV that has shadow/silhouette mayhem at c. 1:17 and c. 3:12. That’s not what I remember from the movie–it’s probably taken from the TV series–but it makes the point I believe.

Collin Street 11.26.17 at 10:16 am

You should watch Utena TV if you can. It’s brilliant in its own right, and the way it deliberately played into archetypes and artificed staging — theatricality — was ten years ahead of its time.

Plus, shadows!

Adam Roberts 11.26.17 at 10:35 am

Bill: Jungle Book a drag? No film with songs the calibre of “I Wanna Be Like You” can in fairness be so described.

I teach Disney’s “Snow White” on my Children’s Literature course, and we look at the scene where the Huntsman tries and fails to kill Snow White. Look at the use of shadows in this scene (from 1:30 on in this clip).

Bill Benzon 11.26.17 at 8:12 pm

“I Wanna Be Like You†IS wonderful, Adam. But it’s not the whole film.

The Pastoral Symphony episode of Fantasia does wonder work with reflections in the opening sequence, & here and there throughout. Dumbo too, I’m thinking of the clowns’ silhouettes/shadows on the tent wall, and Dumbo’s own shadow on the earth when first he flies.

And there’s the wonderful use of shadow in the WB classic “What’s Opera, Doc?”

Just did a search on “shadow” over at Splog. Looks like some good stuff here and there in there.

Comments on this entry are closed.