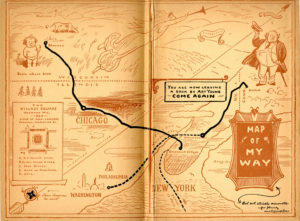

Today I conclude my reflections on Art Young, occasioned by the great new book about him [amazon associates link]. For those disinclined to purchase, I found a copy of one of his books, On My Way (1928), in free PDF form. (Doc announces itself as legal. No copyright renewal, so it seems.) Anyway, in honor of my earlier, literary maps post: say! the endpapers make a swell map!

But the Art path I shall trace in this post is not from Monroe, WI, to Bethel, Conn. A few years back I published a survey article on ‘caricature and comics‘. On the one hand, caricature is a minor art form – not necessarily low but distinctly niche. Funny line drawings of celebrities. On the other hand, formally, caricature is very old and very broad. This produces categorial dissonance. Caricature techniques are at the root of styles we don’t think of as caricature. This is the main thesis of Gombrich’s Art and Illusion, by the by. (No one seems to have noticed, but it’s true.)

In that essay I make some points with reference to the case of caricaturist-turned-Expressionist, Lyonel Feininger, but I could have used Art Young.

But let me start at the beginning, regarding Young. I like reading stories of youthful artistic influence, so here is his, pieced together from the new book and other sources.

He was a huge Doré fanboy.

There is a charming passage from this book – I’ll just quote it.

Dante’s Inferno was the first book to give me a real thrill. I thought Doré’s drawings in it remarkable, and I became exceedingly curious about his work. No one in town owned a Doré Bible, the highest priced table book of the period, but I soon began to see Doré’s pictures in magazines. Who was he? Then a man came to town opportunely and lectured about Doré in Wells’s Opera House. Admission 15 cents. It seems strange that the visiting lecturer on that subject could have hoped to draw much of an audience in a town of 2,000 in 1881. But there was a good turnout – and I suppose the explanation is that anyone coming to a town of that size to lecture about anything was an event.

That was a great night for me. I was the town’s fifteen year-old prodigy in art, and I remember the people turning to look in my direction as a the speaker proceeded. Edith Eaton leaned over and said: This ought to interest you, Artie.” I sat there fascinated, especially by the lantern slides of the imaginative Doré’s paintings and illustrations.

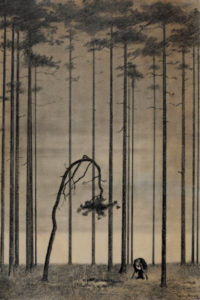

Jump ahead 40 years. In 1922, after being sued for libel by the AP, and twice indicted by the US government for sedition, Young gets an offer to publish cartoons in the Saturday Evening Post, despite that publication’s conservative profile. (Yes, he thought it was peculiar that they wanted him, too.) He contributes a series, Trees At Night, which are (we would say today) kinda Expressionist, stylistically. (The new book contains very nice reproductions of the original art, as well as a nice essay on Young’s treescapes by Justin Young.) In deference to copyrights on that original art, I’ll show you how they looked originally in print, courtesy of this old post.

One interpretation might be: Art Young is just late to the European, post-Impressionist, Expressionist party. From a museum catalogue on my shelf [amazon associates link]: “Just as the market for Expressionist prints was heating up in the early 1920s, artistically the movement was winding down. Expressionism had failed to bring about revolution and instead evolved into a popularly accepted style, avidly collected by the bourgeoisie that many of the artists had originally denounced. Although the leading Expressionists and Post-Expressionists were still creating outstanding prints during the immediate postwar years, in terms of innovation it was the Dada artists who now led the way.”

One might add: a lot of this stuff looks proto-Disney. It wouldn’t surprise me if the “Ave Maria” scene in Fantasia owed something to someone having seen this.

Nice! But, some might say, a step back from the harsh boldness of the early days of die Brücke, Klee and Kandinsky!

But there’s another way to tell it. Per this old post of mine, Doré was always a master caricaturist, as well as great for all those engravings of Hell.

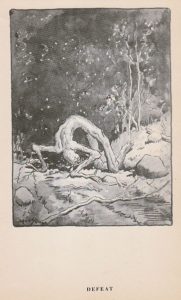

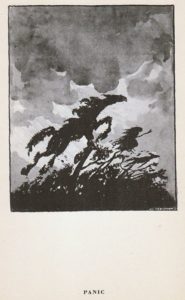

Art Young is, early on, influenced by Daumier, too. The wavery lines in his “Defeat” tree are a Daumier signature, and an expressive horse silhouette might come from his Quixote paintings.

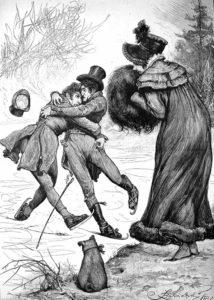

Young writes about admiring the caricature art of Fred Barnard, who did a lot of Dickens illustration. Here’s a nice one, “The Rivals Embrace”, which suggests where some of the later leg work – maybe in Seuss as well – might be coming from.

Young also admired, early on, the battlefield art and illustration of R. Caton Woodville, Jr (who was a student of Gerome, evidently.) Lots of dramatic horses. He also did some H. Rider Haggard illustrations for the Illustrated London News, and Young specifically mentions that paper as a source of graphic inspiration.

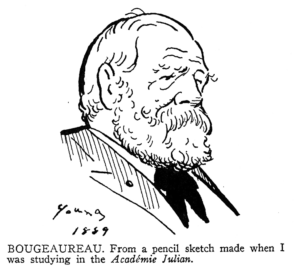

Young actually studied art for about a year in Paris, and his teachers were Bougeaureau and Fleury. Young did a caricature of Bougeaureau, which is neat! I’ve never seen it before. (I’ll bet some Bougeaureau scholars don’t know it exists!)

So Young got a brief but standard, French academic education. His comments on the state of modern art in 1888 are interesting.

Bougeaureau was then the high priest of French painters. I liked his work, for its thoroughness of draftsmanship and his ability to impose beauty over realism, though his art was being assailed as sentimental “candy-box stuff” by both realists and impressionists.

And:

One day I had sketched a big-muscled male, and Bougeaureau came around inspecting our work. When he saw my drawing, he commented, with vigorous shoulder-shrugging. I didn’t understand French, and it was my custom to ask a fellow-student named Robert Henri what the instructor had said. “He says your drawing is too brutal. The model looks brutal enough without making him more so.”

But I knew that Hogarth, Daumier and Doré also had been brutal in portraying brutality, an that caricature meant the ability to exaggerate. Indeed, that all good art had this quality in some degree.

Art Young doesn’t seem to have much sympathy for, or antipathy for, or interest in, ‘modern art’ movements in the 20th Century. He doesn’t write about it. He’s a cartoonist. No cartoonist can resist indulging a few modern art-is-funny gags. He’s got some. But he also makes fun of caricaturists, reserving special punishments for them in hell. Fair is fair.

He writes about how he met and admired John Shirlaw “a great artist now neglected”. And

the picturesque DeLeftwitch Dodge, who was one of the promising wizards of sensual and fantastic murals even in the days when we were both at Julien’s in Paris. The last time I saw him he was teaching at the Art Students’ League – and in one of those casual street talks with him it was plain that the tendency of the younger generation to see some merit in the new cult of Picasso and the other modernists aggravated him.

I infer from the tone that Young himself was lukewarm on Picasso-type stuff. All the stuff that really excites him seems a bit old-fashioned.

Back to Expressionism. Like I said, you might suspect Young was peddling some lightweight, late-to-the-Expressionist party stuff to the Saturday Evening Post, to pay the bills. But I say he was just staying true to his roots, and the branches were ending up in the same place as Expressionism, which says something.

Some folks say Expressionism starts, treescape-wise, with Klee’s “Virgin In A Tree” (1903). Some folks might point to earlier, French influence on later German work. The same year Young was caricaturing Bougeaureau, van Gogh was painting “Pollard Willows At Sunset, Arnes” [scroll down].

The correct answer is: the answer is simpler. Expressionism is a caricature style. It grows out of caricature. It grows alongside stuff you see in German satirical magazines – in Simplicissimus, say. Which starts in 1896. But all that hearkens back to earlier, French and English work. To Daumier, especially.

There is a tendency to downplay this, on behalf of the art ‘ideology’ of Expressionism. (I know, I know, it’s not like there was one party line. I’m oversimplifying for blog post purposes.) It was opposed to realism and naturalism, also to Impressionism (allegedly, the way light and color ‘really appears to us’). Expressionism self-styles as ‘inner’ – self-expressive. (Hence the name.) This style of self-advertisement discourages attention to two really rather obvious features.

First, medium-wise, it’s predominantly an illustration style, graphically. This point is very well made in a very nice book, from 1974, which I highly recommend: Lothar Lang, Expressionist Book Illustration in Germany, 1907-1927 [amazon link.] The author heroically combs through books and magazines and archives and libraries and collections, coming up with 157 artists and 380 works. He grumps about the fact that this labor is necessary.

It may seem odd that there has been no detailed study and appreciation of Expressionist illustration of literary works before now. The argument that the prejudices of conservative book-designers and typographical fetishists have stubbornly endured for all these years and are the true explanation of current disregard is one that cannot be taken seriously. It is to say the least surprising to watch bourgeouis art-historians extolling Expressionism and at the same time treating Expressionist illustration with shy reserve. (6)

The scholarly situation has gotten rather better since. (There is still a shy reserve with the word ‘caricature’.) But that it was so blinkered in 1974 says something.

Expressionism is (unlike Daumier or Doré): all cuts and angles rather than pen-and-ink curves and sketchiness. This is due to all the woodcuts. But woodcut is not for fine art pieces, for some museum wall. Woodcut is for printmaking, for publishing. That it would ever seem strange to associate Expressionism with illustration, given its strong association with woodcut printing-making is … really strange. But there was a will to make Expressionism … expressive. And the illustrator really does not get to be that first. The illustrator is semi-subservient to a subject. And that seems rather intolerably un-Expressionist. ‘Illustration’ is not mystical-sounding enough. Yet Expressionism is an illustration style.

Second, formally – functionally – Expressionism ‘works’ the way caricature does: it achieves a strikingly strong recognition response, yet without appearing strongly to resemble its intended subject. But this is just a different illusionistic trick, not non-illusionism. To conjure a face with just a few cuts is a … conjuring trick. But Expressionism doesn’t think of itself that way. It wants to think of itself as radically breaking with the stagy illusionism of the tradition, when the truth is that caricature techniques are just a few tricks out of the bag of pictorial illusion tricks. What Expressionism offers is not any new technique, but simply a will to put forth, as finished, something Bougeaureau would regard as appallingly unfinished. A sketch doesn’t have to be a preliminary. Expressionism is the tradition truncated, for effect – not the tradition overthrown in revolution. (And being brutal is ok. That, too. But caricaturists knew that already.)

Getting back to Art Young. There’s no way the Saturday Evening Post would have been interested in him publishing a series of expressionistic treescapes if Expressionism weren’t a European art style that was a bit past its avant garde prime – hence it was suitable for the Post‘s conservative readership. So Expressionism shifted the aesthetic Overton Window, as we might say today. But the room that shift gave Art Young to move was room in which he practiced old-fashioned stuff, which was – all the same – formally indistinguishable from Expressionism. Stuff he learned from Doré. One last quote from Young.

Doré had at least one admirer who accepted all that he did – painting, cartoons, statuary, and illustrations – as beyond criticism. A young man from Wisconsin who thought he understood him and counted him the greatest artist of his time. I estimated the gift of imagination in all of the arts as supreme. And Doré had it. Rowlandson, George Cruikshank, the elder Breughel, Gillray, Callot, Durer, and Oberlander also had it in the graphic arts, as did most of the Renaissance painters. But Doré’s torrential ambition and his over-production not only killed him at fifty-one – it deadened a decent appreciation of his work. He was a sensation, and it may have been only “for the day thereof.” Time will tell whether much of his work will survive.

{ 10 comments }

eg 02.06.19 at 10:51 am

Thanks for this — put me in mind of Beerbohm, given the emphasis on caricature.

Jennifer Krieger 02.06.19 at 7:39 pm

I dip in here from time to time. A most interesting essay. Thanks for introducing me to an entirely new person.

John Holbo 02.06.19 at 9:52 pm

Thanks!

Doug K 02.06.19 at 10:41 pm

thank you, fascinating.

The visualHaggard.org site is astonishing, I had no idea there were so many illustrators..

the link here goes to R. Caton Woodville though, and I don’t find any Young in their list ?

alfredlordbleep 02.07.19 at 12:21 am

Some striking images in your piece, JH.

For the non-specialist like me there’s this (but well-known to the cognoscenti here?):

[Heinrich] Kley attained greater notoriety with his sometimes darkly humorous pen drawings, published in Jugend and the notorious Simplicissimus.

. . . Cartoonist Joe Grant was well aware of Kley’s work and introduced his drawings to Walt Disney, who built an extensive private collection. A number of early Disney productions, notably Fantasia, reveal Kley’s inspiration.

Due to Disney’s interest and reprints by Dover Publications, Kley is still known in the USA, while he is nowadays little regarded in Germany.—Wikipedia

I’ve had Dover’s two volumes of Kley since student days. His stuff goes from obvious (political) to bizarre to obscure. Couldn’t find his curious All Souls’ Day despite a bit of a search on Google and Bing.

example:

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/565835140660820751/

John Holbo 02.07.19 at 12:04 pm

Hi, alfredlord, Kley is a real favorite of mine!

https://crookedtimber.org/2013/04/10/heinrich-kley-on-politics-and-metaphysics/

Another Nick 02.08.19 at 2:31 am

Thanks John, really interesting.

I think you’re pretty spot on with the ‘crippled tree’ image as an influence for the Disney artists. Some of Kay Nielsen’s earlier work prior to his art direction on Fantasia is reminiscent, but Art Young’s ‘dead straight sparse trees’ are kind of unique, and it looks like a straight up rip. They were using 6 or 7 layers of glass in front of the camera to create that same depth and layering we can see in Young’s image.

Later in the scene, the foliage starts to look like ukiyo-e bamboo groves. I came across Russian illustrator, Ivan Bilibin, a few months ago, who also studied in Munich. I find his images striking, and a real halfway point between Japanese woodcuts and Disney cel animation. I haven’t seen anything else quite like these from the late 1890s. Check out the shadows beneath her dress. He also does a great Baba Yaga.

Mainmata 02.08.19 at 4:11 am

This was a really fascinating essay on a subject in which I am really interested. I used to do cartooning regularly (even appearing in Carter’s NSC, which surprised me). And practicing various media my whole life while making a career in a different environment (the environment). But, reducing Expressionism to a version of caricature seems wrong. Yes, a lot of it had political messaging. But German and, especially post-war (then) Czechoslovakian and other eastern European expressionist art had a surrealist, political and sometimes semi-erotic content (thinking of the Brunovsky school and others). I happen to be a real fan of that art. But “Expressionism” in art exists in non-European art too: for sure Latin America, also parts of Southeast Asia (Indonesia for sure, which I know about).

John Holbo 02.08.19 at 6:43 am

“But German and, especially post-war (then) Czechoslovakian and other eastern European expressionist art had a surrealist, political and sometimes semi-erotic content (thinking of the Brunovsky school and others). I happen to be a real fan of that art. But “Expressionism†in art exists in non-European art too: for sure Latin America, also parts of Southeast Asia (Indonesia for sure, which I know about).”

I don’t disagree with this. The proper response – I spell this out better in the linked essay – is that caricature, as a technique, should be regarded as at the root of all that other stuff, too. I’m not reducing Expressionism to caricature (a major modern art movement to a niche category of funny faces, mostly of celebrities.) Rather, I ‘m pointing out that caricature should really be regarded as a much more commodious category that encompasses the niche products we think of as ‘caricature’ but a great deal else instead, including Expressioinism. A lot of things work the way that the things we call ‘caricature’ more obviously work – so those niche-seeming items are formal-functional paradigms.

Suppose we distinguish Narrow Caricature (funny pictures, mostly of celebrities) and Broad Caricature (a lot more stuff.) Expressionism is more caricaturish in BOTH senses than it sometimes admits.

I didn’t really get the full-dress argument into the post, so I’m sure I was misunderstandable on that point. It is likely that you are using ‘Expressionism’ – broadly – to mean exactly what I mean by ‘caricature’, broadly. Which is fine, and we aren’t really disagreeing, except the terms get confusing.

But glad you liked the post!

John Holbo 02.08.19 at 6:46 am

Thanks for the links, Another Nick!

Comments on this entry are closed.