The central idea of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), as I understand it, is that, rather than worrying about budget balances, governments and monetary authority should set taxation levels, for a given level of public expenditure, so that the amount of money issued is consistent with low and stable inflation. In this context, the value of the net increase in money issue is referred to as seigniorage. To the extent that seigniorage is consistent with stable inflation, it is achieved by mobilising previously unemployed resources.

A crucial question is: what is the scope for seigniorage? In particular (expressing things in MMT terms), is the scope for seigniorage sufficient to permit the introduction of ambitious programs like a Green New Deal without the need for higher taxes to prevent inflation.

The recent episode of Quantitative Expansion in the US provides some evidence here. Contrary to the dire predictions of some critics, QE did not lead to runaway inflation. This is consistent with the view, shared by MMT advocates and mainstream Keynesians, that, in the context of a liquidity trap and zero interest rates, there is substantial scope for monetary expansion.

How much is “substantial”?

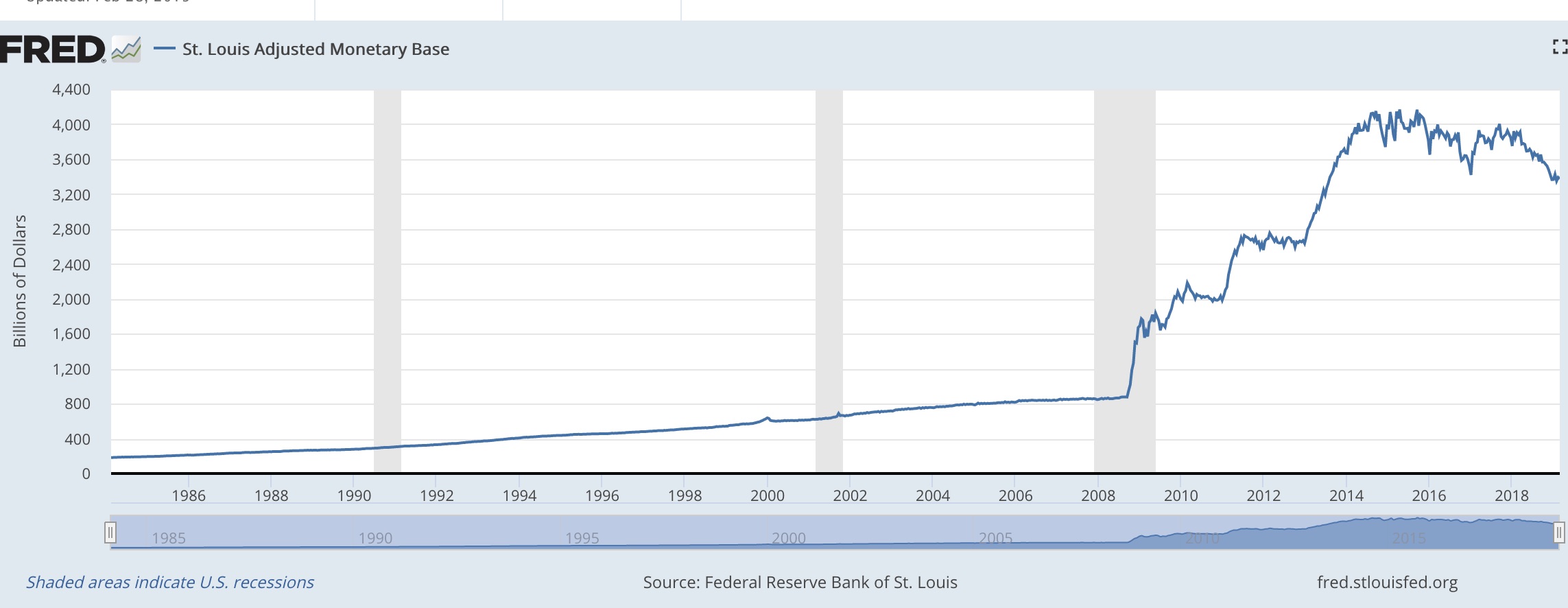

According to the St Louis Fed,

the monetary base grew from around $800 billion to just over $4

trillion between 2008 and 2016. That’s an increase of $3.2 trillion,

which is a lot of money. Expressed in terms of GDP, though, it doesn’t

seem quite as large. Over eight years, $3.2 trillion is $400 billion a

year or around 2 per cent of US GDP ($20 trillion).

Assuming that this is an upper bound for the scope of seigniorage, it’s much smaller than the amount needed to finance, say, a Green New Deal.

What qualifications need to be made here? First, it might be argued that QE should have been more aggressive than it was. Certainly, looking at things with a focus on the real economy, as traditional Keynesians do, the stance of fiscal and monetary policy overall was too restrictive. But, if you assess things on the MMT criterion of low and stable inflation, the Fed got it pretty much right. Deflation was avoided, and the inflation rate was restored to the target level of 2 per cent in a reasonably short time. That’s continued as QE has been partially reversed in recent years.

A second point is that QE wasn’t (directly) an expansionary fiscal policy of the kind Keynesians favour. Rather, the budget deficit (smaller than it should have beeb) was financed with bonds. The sale of these bonds to the public would have depressed demand, but instead the Fed bought them (and also some high-grade corporate bonds). That’s not the best way to stimulate the economy, but from an MMT viewpoint it’s not obvious that it matters (interested to get comments on this).

Overall, the evidence of QE suggests to me that the basic idea of MMT is sound, at least in the context of a llquidity trap. On the other hand, the same episode shows that a widespread interpretation of MMT, that we can greatly expand public expenditure with no corresponding increase in taxation, is both wrong and inconsistent with the core idea of MMT.

{ 39 comments }

Kevin Bryan 03.06.19 at 10:45 pm

John,

As one economist to another – this is far far too kind to the MMT crowd. The basics of their theory, and I hesitate to even call it that, are totally ridiculous, and I know of no serious economist who had plowed through the mass of word games they play and learned anything useful.

On the precise question of QE: had there been a increase in monetary base that led to 3.2 trillion of real resources being consumed, surely we all agree that, whether at the current moment or in 2008, there would have been significant inflation. QE is not at all comparable on dollar terms to expansionary fiscal policy – I don’t even know how to map the two terms. Indeed, were it comparable, the winding down of QE would be causing massive deflation and a recession!

*Even if* there are unemployed resources, expansionary fiscal policy is noninflationary only if the resources consumed by that expansion are the unemployed ones. That is, if there are unemployed stockbrokers, and full employment among solar engineers, financing a GND through MMT-type ideas is inflationary from the first dollar.

None of these statements require literally any obscure models. The fact that these statements are not obvious to, or deliberately muddled by a handful of elderly financiers and heterodox economists with no independent research of any note, does not mean the rest of us need to waste any time on them. Linking QE – which is justified on the basis of dozens of papers by some of our finest macro thinkers, and is essentially just about increasing held reserves in the financial sector which maybe doesn’t result in any additional consumption of real resources (empirically there remains debate) – and MMT – which argues that real resource consumption at large scale through de facto fiscal policy is noninflationary, is nuts. Just because a handful of misguided politicos listen to these folks doesn’t mean the rest of us have to.

Rapier 03.06.19 at 11:51 pm

What is missing in this is that the inflation that QE rendered was in the prices of financial assets. Of course that statement is almost incomprehensible to most people because assets especially financial ones are never said to inflate. They are always said to ‘increase in value’, or some such thing.

There is a very mechanistic reason why QE inflates the prices of financial assets and that is because central banks buy financial assets. They don’t by steaks or cars or big screen TV’s. The US Fed bought Treasury Notes, and Mortgage Backed Securities. (Not high grade corporate debt) The ECB bought corporate bonds. If of high grade is another question.

On the most basic mechanistic level it has to be understood that the increase in the prices of bonds and other debt securities is lower interest rates. Not like lower interest rates or analogous to lower interest rates, they are the same thing. A higher bid price for a bond is a lower interest rate. The relationship is inverse. The same thing applies to the purchase of MBS or any debt instruments but let me speak in terms of Treasury paper.

The Fed and other central banks purchased already issued securities in the open market. Obviously they purchased them from holders of said securities. Those being banks, other institutions, and money managers for the top 1%. With the money from the sale did they go out and buy a new Ford? No, they bought other financial assets and since the grade of bonds they sold were now offering a lower return than when they bought them, while pocketing a capital gain, they went looking for higher yielding assets, or, crucially, stocks.

With $15TN in additional liquidity provided by the worlds central banks injected directly into the financial system a bull market in stocks started. Exactly 10 years ago, coincidentally. Rising stock prices attracted more stock buying and so around again in a virtuous circle. Not to forget the increase in demand for lower quality debt, 50% of all US outstanding corporate debt is now at the lowest ‘investment’ grade. The flood of seemingly endless credit did spurn the expansion of some real businesses that created jobs.

I run on too long. The prices and mark to market ‘value’ of financial assets has dwarfed the growth of GDP. Here is a link to a simple chart of this and I apologize for the rhetoric embedded. And I am not a gold bug.

http://www.goldseek.com/news/2018/1-5dk/2.png

I could haul out the very old fashioned reasons why rapid monetary expansion is a devils bargain. It is now fruitless to fight this round of it because there is going to be more and more and more again because without added central bank liquidity there will be incidents of sudden freeze ups in the capital markets, again. The good thing is that GDP economies will continue to expand and make jobs. The bad thing is the obscene skewed distribution of ‘wealth. measured by the mark to market prices of the assets held by the few will grow and grow more and more. And those will more will want more yet again.

otpup 03.07.19 at 12:36 am

Afaik, MMT advocates do not specify that taxation is the only (or even necessarily the preferred) method for combating inflation.

Rapier 03.07.19 at 1:28 am

RE Kevin: QE is not at all comparable on dollar terms to expansionary fiscal policy – I don’t even know how to map the two terms. Indeed, were it comparable, the winding down of QE would be causing massive deflation and a recession!

QE put in rolling periods of demand for Treasury paper which subsidized the at first massive Treasury supply of 09 and then falling but still large amounts in 10 and beyond. On the most fundamental level it funded expansionary fiscal policy. Period.

On deflation see my above post. The inflation was the higher than would otherwise have been price of Treasury debt. Absent the Fed buying $2.5TN of Treasury notes their prices would have been lower. (interest rates higher of course) Also as described the injection of liquidity, money, directly into the financial system lifted bids for all financial assets. As to the deflation if QE is unwound. We started to see it in Q4. Admittedly this was exacerbated by the now huge waves of Treasury borrowing as the deficit is rising strongly towards 5% of GDP.

But all this QE stuff is off in the MMT weeds. I never heard of MMT talk include QE until this very moment. Before now it was always ‘currency issued’ and other such things. Or worse yet, trillion dollar coins. Thinking evidently that the Treasury creates money by ‘issuing currency’ never mind all currency now is Federal Reserve Notes, the Treasury having nothing to do with it and in any case that currency does not create money. As I said the trillion dollar coin is worse because, and while it is simple to say this but impossible for most to grasp, that there is no way to ‘deposit’ said coin in a bank so that a check can be drawn against it. Not under current law or at least inclination of the Fed and the banks. Remember the Fed is not the government.

All money today is created in one way, by two methods. The one way is to create a bank deposit, out of nothing. First when banks make a loan they create the deposit, out of nothing. Second Central banks create a deposit in the account of the seller of the Treasury or other security they purchase from them. Create said deposit out of nothing.

Don’t believe me. Believe the Bank of England.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CvRAqR2pAgw

Now I hate to have to go here, to the beginning, but unless people have a clear understanding of what money is then this MMT nonsense can’t even begin to be discussed. There are other ways money could be created, in theory.

Nicholas 03.07.19 at 1:51 am

“*Even if* there are unemployed resources, expansionary fiscal policy is noninflationary only if the resources consumed by that expansion are the unemployed ones. That is, if there are unemployed stockbrokers, and full employment among solar engineers, financing a GND through MMT-type ideas is inflationary from the first dollar.”

Kevin, that is precisely why MMT scholars advocate targeted labour management rather than aggregate demand management aka generalized stimulus aka “pump priming”.

A Job Guarantee that pays a living wage that sets the wage floor for the economy is the key mechanism for maintaining full employment alongside price stability. The JG hires off the bottom – it employs a resource (the labour power of unemployed people) that is currently not being used by the private sector. The size of the JG workforce varies automatically in response to the private sector’s demand for labour.

There would be modest variations in the size of JG workforce from the peak to the trough of the business cycle.

Wray, Fullwiler, Kelton, and Dantas use econometric modelling (the Fair model) to simulate the macroeconomic effects of a JG in the USA from 2018 to 2028. A JG would always be a small but essential segment of the total labour force. Wray et al estimate that initially a JG in the USA would employ about 15 million workers and in the long run this would likely settle down to a smaller size.

http://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/public-service-employment-a-path-to-full-employment

You are correct that fiscal expansion that pays market wages and therefore competes with the private sector for real resources can bid up prices. That is why MMT scholars warn against pump priming and advocate a JG as an essential automatic stabilizer, along with discretionary fiscal policy decisions based on careful assessments of real resource availability in specific sectors and industries. The chief purpose of an MMT-informed JG is to provide macroeconomic stability. It stabilizes prices and it stabilizes variations in private sector spending, employment, and output. It isn’t just a public sector jobs program.

MMT scholars have produced an extensive and rigorous literature over the past quarter century. This includes high quality theorizing about inflation and how to prevent it.

Nicholas 03.07.19 at 2:06 am

The MMT read on QE is that it is a monetary policy operation, not a fiscal policy operation. QE does not change the amount of net financial assets held by the non-government sector. All it does is enact a portfolio reshuffle. Private sector entities sell bonds to the currency issuer and get reserves in exchange. In other words, the composition of the non-government sector’s financial wealth has changed, but the net amount of assets has not changed at all.

QE is based on the false belief that banks make credit decisions based on their reserve positions. The orthodox neoclassical economists (who include ‘New Keynesians’) think that if banks have fewer bonds and more reserves, they are more likely to lend. This is incorrect. Banks lend if they see a profitable opportunity to lend. They sort out the reserves later. The MMT scholars have by far the most thorough understanding of the operational realities of the financial system.

MMT scholars point out that monetary policy is a weak and imprecise policy tool for influencing economic activity. Corporations won’t borrow in order to expand production if the customer demand for the extra output simply isn’t there. Even if the interest rate is zero, corporations won’t borrow to finance production that can’t be sold.

Sales expectations determine the borrowing decisions of firms.

Assessments of credit worthiness and profit expectations determine the lending decisions of banks.

Mainstream economists mostly subscribe to the erroneous “loanable funds hypothesis”. They think that if the government converts one kind of highly liquid financial asset (government bonds) into a slightly more liquid financial asset (government reserves) that the commercial banks will lend more and productive firms will borrow more and produce more. They are wrong to believe that.

There isn’t a pot of loanable funds and the banks are not intermediaries between deposits and loans.

Bank lending creates deposits.

Kevin Bryan 03.07.19 at 3:17 am

Nicholas,

A jobs guarantee may or may not be a good idea, but it sure isn’t MMT – it’s neither modern, nor monetary, nor theory. My prior is that there are much better ways to employ folks – indeed, the main justification for unemployment benefits is that they give people time and money hence induce longer searches for new jobs and therefore better matches. Make-work jobs are the opposite. But in any case, that’s a reasonable debate one could have, and it has nothing to do with the problematic parts of MMT. Nor does the general idea of automatic fiscal stabilizers – they are in every orthodox macro textbook!

Same with the idea that “monetary policy is imprecise” and often doesn’t work – indeed! Everyone in standard macro understand this (I attended pre-FOMC meetings from 2006 to 2008 when I was a young buck – I remember the debates well). The complain you give about QE is identical to the one a skeptical neoclassical economist would give!

Nevil Kingston-Brown 03.07.19 at 3:48 am

Bit of a No True Scotsman fallacy from Kevin Bryan there. No ‘serious economist’ can learn anything from MMT, and the definition of a “serious economistâ€, as opposed to “elderly financiers or heterodox economists†is apparently “does not believe or find any value or interest in MMTâ€.

“No serious economist finds anything in the word games played by capitalist economists to cause then to doubt the Labor Theory of Value. None of Marx’s thought requires any obscure models and the fact that it is deliberately muddled by financiers and a cohort of capitalist stooge economists in bourgeois universities does not mean that the rest of us should listen to themâ€

nastywoman 03.07.19 at 4:38 am

”The central idea of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), as I understand it, is that, rather than worrying about budget balances, governments and monetary authority should set taxation levels, for a given level of public expenditure, so that the amount of money issued is consistent with low and stable inflation”.

It might be high time to bring this ”theory” down to reality – and finally tell the people ”whassup” with this whole deal?

As we finally have found out -(or haven’t we?) that the only country on this planet which doesn’t have to worry about ”budget balances” seems to be the US one?

All others get punished – or should we call it ”played” by our Rating Agencies – and then by ”TEH Almighty market -(aka the ”money slosh”) if they play too much of the ”Debt-Game”?

Right?

And about this ”Inflation Thing” – it is currently ”horrific” in my homeland – as I’m not the only one who currently is screaming about Hotel – Restaurant and Aperol-Spritz Prices in Miami Beach… and as I yesterday -(on my rusty 50 dollar-beach-bike) AGAIN – nearly got run over by a (golden) Lambo – I had a talk with the (cute) driver – and you guys should have heard him complaining about ”THE inflation on wheels” – which reminds me – do you guys know that the US Trade deficit mainly get’s produced by ”automotive” – with over 250 billion in Imports and only about 150 billions in exports? – and if you stay in SOBE you get the impression that all of the utmost ”inflated wheels” – with 8-12 and even 16 cylinders – are blowing away the climate right here?

So what’s about writing a book how in these very ”unequal times” – even ”inflation” has become ”unequal” to the utmost degree – IF a newer Bugatti suddenly has a 30 to 40 percent higher sticker price than two years ago?

– and at the same time I – last week – got a really good ”bike-lock” for 99 cents at a 99 Cents Store on State Street in Santa Barbara.

BUT at this funny Fointenbleau -(a truly horrific hotel) Americas (College Youth) was downing 25 dollar drinks like nothing last tuesday?

What does MMT say about that?

nastywoman 03.07.19 at 12:11 pm

correction@9

”with over 350 billion in Imports and only about 150 billions in exports”

Alwalad 03.07.19 at 12:32 pm

@Kevin Bryan

“*Even if* there are unemployed resources, expansionary fiscal policy is noninflationary only if the resources consumed by that expansion are the unemployed ones. That is, if there are unemployed stockbrokers, and full employment among solar engineers, financing a GND through MMT-type ideas is inflationary from the first dollar.”

Bit of a lump of labour fallacy there, no? you might see an increase in prices early on, but afterwards, the incentives would cause new entrants to come in, people to change jobs, pushing prices down, so no little to net effect.

Omega Centauri 03.07.19 at 2:22 pm

To get to Kevin’s point vis-a-vie stockbrokers and solar engineers. Clearly any rationally applied GND has to be involved with workplace training/retraining. Since that is not an instantaneous process any renewables expansion will have to gradually ramp up over time probably over several years.

MisterMr 03.07.19 at 2:30 pm

There is a thing that irks me in MMT (but I’m starting to think that this is not limited to MMT but also to many other variants of keynesianism), and it is the conflation of the increase in the quantity of money with increased demand.

For example this sentence from the OP:

“In this context, the value of the net increase in money issue is referred to as seigniorage. To the extent that seigniorage is consistent with stable inflation, it is achieved by mobilising previously unemployed resources.”

Basically the idea is that there is a certain quantity of money around, that corresponds to a certain level of production. If you dump more money, first of all production increases (for some reason), thaen when production can’t increase anymore the increase in the quantity of money leads to inflation.

This could be described as a really old-styled theory of prices, that works like this:

(price level) = (quantity of money)/(quantity of stuff)

Now, if we take this idea seriously, during recessions the quantity of stuff decreases so we should have inflation, whereas during booms the quantity of stuff increases so we should have deflation.

In reality the opposite happens: during recessions there are deflationary tendencies, whereas during booms (even if those booms are not caused by economic stimulus) there is increasing inflation.

This happens because the phenomenon that we call “inflation” (actually demand-pull inflation) is a wage price spiral: as employment goes up worker can demand higer wages, but businesses also have more buyers so they can increase prices, whereas during busts unemployment increases, wages tend to fall, but businesses are forced to lower prices in part because unemployed people buy less stuff, and in part because the reduced level of investment directly lowers aggregate demand.

So what happens is that the price level is the independent variable, and the “quantity of money” is either irrelevant or non existent: non existent because, if we think of nominal GDP, this is just the number of transactions multiplied by the price level, not a “thing” in itself, or irrelevant when instead we speak of the “quantity of money” meaning credit assets – but the ratio between credit assets and nominal GDP isn’t fixed by anything so the growth of credit assets doesn’t directly influence GDP.

Even this difference between the quantity of credit assets and nominal GDP seems to be elided from the discussion.

My point is that keynesian measures increase demand (and/or inflation) by (A) directly employing people or (B) by bumping up business profits[*], and thus enticing businesses into additional investment, NOT by simply increasing some misterious quantity of money.

[*] this happens obviously when stimulus comes from lower taxes, but also by the government spending more in services without increasing taxes, because it creates new buyers for whom businesses don’t have to pay wages.

mpowell 03.07.19 at 2:43 pm

Of course you have to consider long term trends differently from short term transients. The past 10 years certainly does not indicate anything about stable long term trends as we had continuously dropping unemployment for the entire time – this was entirely a transient response to the last economic crash.

Overall, I doubt you can grow the monetary base at more than the rate of inflation you are targeting in the long term, and I also doubt a monetary base the size of national GDP is desired. There is probably something to be gained here and the fed should be far less hesitant to do QE to respond to adverse market events, but it is not, as you point out, going to be a funding source for major social programs.

Anarcissie 03.07.19 at 3:44 pm

I hadn’t thought of automobiles as a destination of the money hose. What a lack of imagination! I had been thinking instead about draggy stuff like stocks, bonds, real estate, collectibles, elite education, and other such toys of the rich. In my homeland (NYC) the inflation of real estate ‘values’ has been truly grotesque. A few months ago I looked at a teardown on a small lot sort of near Long Island City, for which they were asking over a million. But money never sleeps, and it has to go somewhere. Even funny money, evidently.

I’ve been to Miami Beach recently, though; I bought a single-scoop ice cream cone on the boardwalk for almost $8. $2.50 – $3 in Queens. So — ice cream cones too!

Trader Joe 03.07.19 at 4:50 pm

I’d just second one of the points made by Nicholas @6 that a lot of the monetary base expansion was really directed to providing deeper bank reserves which (appropriately) corresponded to increased capital requirements mandated by Dodd Frank. These increased reserves not only didn’t get lent – other aspects of D-F made it harder to lend even if the banks wanted to. This isn’t to be critical of D-F, its just to say that some amount of the increase in base was really entirely non-stimulative.

I’d add that the Fed has implied they are about done with reducing their asset portfolio and that’s expected to leave the Fed balance sheet in the $3.5-$4T range. They have said themselves that they view that level as essentially neutral with the $1T or so they used to be at after allowing for various policy changes. Accordingly, at the margin, maybe $1T-1.5T was designed to be ‘stimulative’ and the balance was essentially permanent policy adjustment which inflated money supply on a gross basis, but did little if anything to inflate it in the actual circulating economy.

Rapier 03.07.19 at 8:48 pm

RE: As we finally have found out -(or haven’t we?) that the only country on this planet which doesn’t have to worry about â€budget balances†seems to be the US one?

One of my favorite spitballs to send in the direction of the MMT crowd is exactly that. It is US specific. Well Japan is the other exception. Wouldn’t Venezuela Argentina, Zimbabwe or even Sweden be good candidates? The whole thing is wrapped up in special pleading. Over and above the fact that MMT doesn’t make sense in that its fans can’t or won’t define what money is now and how they would change it. I mean the mechanisms of it all.

I will just add somewhat cryptically that MMT springs from totally abandoning the last vestige of monies store of value function. Becoming 100% a medium of exchange. Something made inevitable probably by today’s pure fiat money at floating exchange rates. I’m no gold bug and maybe it’s time to divorce money from its store of value function. History marches on. We aren’t there yet however. History is littered with attempts to reinvent a better money. Always attended by the promise it will make the masses rich.

John Quiggin 03.08.19 at 12:58 am

Nicholas @5 Thanks for that link. It’s a nice paper, and the results seem plausible, though I haven’t checked closely. But it seems to be traditionally Keynesian in terms of the macro analysis and to assume either bond or tax financing for the net fiscal cost (which is positive, since workers are producing public services but need to consume market goods and services). There’s no mention of MMT at all. From my point of view, that’s fine – the approach is exactly the one I would recommend.

Senexx / AusMMT 03.08.19 at 1:38 am

All those authors are MMTers and MMT is just Macroeconomics done correctly. MMT is Macroeconomics. Macroeconomics is MMT.

I think all economists or at least all macroeconomists should agree with this comment from your former colleague Bill Mitchell: “…Government spending has no intrinsic financial constraints but may have real resource constraints which might impact on its ability to pursue its socio-economic mandate.”

And it is those real resource constraints or bottlenecks that can lead to accelerating and unacceptable inflation.

That is why the new book by Bill Mitchell, Randall Wray and Martin Watts is just called Macroeconomics (https://www.macmillanihe.com/page/detail/Macroeconomics/?K=9781137610669). I look forward to reading your review.

The most recent nutshell piece in my opinion is the piece by John Harvey in Forbes: https://www.facebook.com/groups/mmt75/permalink/2386745938026412/

nastywoman 03.08.19 at 1:45 am

– and about:

”the best way to stimulate US economy”

– I found out -(in California AND Florida) – in the last weeks – you just hike up prices to the utmost degree – BUT only for ”stuff” – which isn’t in any CPI basket –

(like @15 ”designer ice-cream-cones”) –

In order that the idea of there is ”no inflation” stays intact – not unlike the (American-Australian?) illusion – that any type of monetary stimulus is always helpful.

It just isn’t –

when the dough finally doesn’t go to well payed workers – who proudly build the Lambos – and instead some idiots who buy such… such ”stuff” – to rev some hundred of horse powers while crawling up and down Ocean Blvd – just to pretend that they are really really rich –

which with an Italian perspective actually… is… fine – as friends of mine from Sant’Agata Bolognese now also can afford a vacation in Miami Beach and pay 8 bucks for a portion of ice-cream which costs them about an Euro fifty in their homeland.

But when will our ”progressive friends” learn – that this Keynes-thing is GREAT -(for workers) – only if it is spend to create well paying and secure jobs.

Otherwise – it’s as silly as buying a car whith a few hundred PS – in order to drive 50 miles an hour.

Jonathan 03.08.19 at 9:22 am

This from Jo Michell is excellent on MMT

https://criticalfinance.org/2019/03/06/kelton-and-krugman-on-is-lm-and-mmt/

Faustusnotes 03.08.19 at 12:51 pm

I’m no mmter but I thought they explicitly believed that taxation is irrelevant to the basic issues they are discussing, and describe taxation as only important as an explicit tool for redistribution of wealth. Ie you print money, then use taxation to ensure everyone gets some of it (to put it very roughly).

Also surely whether the green new deal is inflationary or deflationary depends on how it is implemented, regardless of whether it is funded by taxation or money printing?

nastywoman 03.08.19 at 1:10 pm

@21

”This from Jo Michell is excellent on MMT”

and it ends with:

”The only real takeaway is that we deserve a better quality of economic debate. People with the visibility and status of Kelton and Krugman should be able to identify the assumptions driving their opponent’s conclusions and hold a meaningful debate about whether these assumptions hold — without requiring some blogger to pick up the pieces”.

So – it really might be helpful that IN TIMES where ”TEH market” -(aka ”the money slosh”) decides what is ”sound” – Paul Krugman should resist bringing up some funny old ”doctrine that fiscal policy should be judged by its macroeconomic outcomes, not on whether the financing is “sound†–

AND in times where the question of ”full employment” has changed into ”employment which pays living wages” -(otherwise it’s useless) – Lerners argument that ”fiscal policy should be set at a position consistent with full employment” – reads a bit like a… a ”satirical joke”?

and about:

”while interest rates should be set at a rate that ensures “the most desirable level of investmentâ€.

How true – how true?

BUT what IS “the most desirable level of investment†in my homeland?

It’s definitely NOT the ”German Way” -(if there is something like that?) – which invests so YUUUGELY in creating ”secure jobs which pay a living wage”?

Rapier 03.08.19 at 1:40 pm

Due to my pathological literal mindedness when I hear about MMT I always think in terms of money. What it is and where it comes from. Silly me. Just like the Feds monetary policy has nothing to do with money neither does MMT. Fed policy is about providing enough of it to keep the financial system liquid. MMT is about keeping the Treasury liquid, somehow.

One thing everyone agrees upon, especially economists and bankers, is that they want more money. More money is always the answer which will fix all our problems. For economists and bankers and financial types this can be explained by the Law Of The Instrument. When the only tool you have is money then the solution in every case is more of it.

Scott P. 03.08.19 at 4:11 pm

I’ve been to Miami Beach recently, though; I bought a single-scoop ice cream cone on the boardwalk for almost $8. $2.50 – $3 in Queens.

Well, of course it’s more expensive there. So much of the ice cream melts by the time it arrives in South Florida.

Cian 03.08.19 at 5:04 pm

The central idea of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), as I understand it, is that, rather than worrying about budget balances, governments and monetary authority should set taxation levels, for a given level of public expenditure, so that the amount of money issued is consistent with low and stable inflation. In this context, the value of the net increase in money issue is referred to as seigniorage. To the extent that seigniorage is consistent with stable inflation, it is achieved by mobilising previously unemployed resources.

I think the other idea they have is that taxation is best thought of as a way of taking money from one part of the economy and redirecting it to another (through spending, or entitlements). And that by removing money from overheating parts of the economy and redirecting it to underutilized parts, they can increase economic activity. Which sounds plausible in theory – the devil is in the details.

I have mixed feelings about MMT. I find chartalism very convincing, and MMT did do quite a good job of constructing a chartalist monetary theory for the post Bretton Woods world. Not perfect (they’re terrible on trade/foreign debt), but considerably better than what mainstream theories of economics have to offer. But in recent years they’ve become a cult, pushing bad policy ideas and pushing dubious analytical ideas. There’s still interesting stuff going on outside the cult (e.g. J.W. Mason who is excellent – as well as many post-keynesians toiling away in obscurity), but Stephanie Kalton seems to have entirely lost the plot at this point in time.

If I was to try and salvage their ideas at this point, I think I would frame it thus:

1) Government spending is simply redistribution of economic activity (taxation reduces it in one area, spending increases it in another area). The question should always be is the economy being directed appropriately.

2) Domestic government debt is mainly just accounting (foreign debt in your own currency is… complicated). To the extent it’s a problem, it’s a problem of accounting and distribution of wealth (interest is a tax that the government pays to debt owners) – and it’s best dealt with in that fashion (by taxing wealth). Short term spending doesn’t have to be matched by short term debt issuance/tax receipts (it is in the US because convention, but there’s no economic law that says it has to work that way), and worrying about those things too much is silly. Large increases of debt are a problem, but they’re a problem of distribution, will probably have negative affects on economic growth (by diverting resources to rentier segments of the economy) and require increases in taxation of the bond clipping class.

Obviously when you look at this way a green new deal is going to need taxation because you’re going to have redirect economic resources on a massive scale. And also when you look at it this way you can see that maybe one can design taxes in such a way that they help nudge economic activity towards better ends. Do you need MMT to understand these points. Probably not, but it can be a helpful tool and is I think a more accurate way of thinking about things (always helpful).

As a framing for public policy projects it could be very useful. It would make it easier to get useful projects off the ground, and maybe help nullify many right wing projects (e.g. privatisation).

Ironically, MMTers should be pushing raised taxes on the wealthy, because according to their theories there’s a huge misalignment of economic resources in the US which could be solved by heavy taxation of the rich. I guess they’re not pushing this stuff because wealthy hedge fund types write many of their checks.

Cian 03.08.19 at 5:06 pm

I think all economists or at least all macroeconomists should agree with this comment from your former colleague Bill Mitchell: “…Government spending has no intrinsic financial constraints but may have real resource constraints which might impact on its ability to pursue its socio-economic mandate.â€

And it is those real resource constraints or bottlenecks that can lead to accelerating and unacceptable inflation.

I think this is true and useful, and if this is all they said that would be fine. It’s really where they go after this that it all becomes extremely problematic…

Cian 03.08.19 at 5:16 pm

@17 I will just add somewhat cryptically that MMT springs from totally abandoning the last vestige of monies store of value function. Becoming 100% a medium of exchange.

Money has always been a medium of exchange. It’s ‘value’ as a store of money has always been secondary, and often been very problematic. For example the US had constant economic problems in the C19th because the supply of money correlated to the supply of silver, rather than the currency needs of the nation.

To be effective money either needs to be based upon another form of value (problematic because the value of money fluctuates independently to the economy), or to have another buyer of last resort (typically the government by demanding taxes of its citizens).

Kurt Schuler 03.09.19 at 5:05 am

In the United States, the huge increase in the monetary base occurred both because of the financial crisis and because the Federal Reserve started paying interest on bank reserves in excesss of the minimum requirement. The Fed’s rate has exceeded what banks could receive from other safe short-term investments. David Beckworth, who has a blog called Macro Musings, remarked on the Fed’s change in policy when it happened and noted its potentially deflationary effect. Yes, deflationary, because shifting funds into bank reserves means less lending to households and businesses than would otherwise occur. George Selgin has elaborated the case in his recent short book Floored!: How a Misguided Fed Experiment Deepened and Prolonged the Great Recession.

Note that among other effects, payment of interest on reserves reduces seigniorage compared to the hypothetical case of a monetary base just as big with no payment of interest.

The scope for seigniorage depends to a large extent on the availability of substitutes for the local currency. In countries with high inflation, people find ways to minimize their holdings of local currency, including using low-inflation foreign currency and saving in physical goods rather than through the local financial system. Even in large, fairly closed economies people have found ways to do it.

Z 03.09.19 at 8:08 am

As someone often a bit frustrated by the tendency of economists to write (trivial) equations without first lying out very clearly their assumptions and especially what alternative assumptions one could make (mimicking the worst of both math and experimental sciences, rather the best, as it were), I also recommend Jo Mitchell’s text linked @21, as well as JW Mason’s explanation, for instance on sound finance vs. functional finance and on where the differences between mainstream macro and MMT lie.

Kristjan 03.09.19 at 11:17 am

Kurt Schuler :

“In the United States, the huge increase in the monetary base occurred both because of the financial crisis and because the Federal Reserve started paying interest on bank reserves in excesss of the minimum requirement. The Fed’s rate has exceeded what banks could receive from other safe short-term investments. David Beckworth, who has a blog called Macro Musings, remarked on the Fed’s change in policy when it happened and noted its potentially deflationary effect. Yes, deflationary, because shifting funds into bank reserves means less lending to households and businesses than would otherwise occur. George Selgin has elaborated the case in his recent short book Floored!: How a Misguided Fed Experiment Deepened and Prolonged the Great Recession.”

That is because they are in loanable funds camp. Paying interest on excess reserves doesn’t shift funds from households loans. Banks don’t use reserves to make loans to the real economy.

Kurt Schuler 03.09.19 at 7:55 pm

Kristjan, reserves and loans are competing assets. The mix that banks hold depends on their judgment of risk versus return. Imagine that instead of paying interest on excess reserves, the Fed started charging a penalty. Your statement implies that banks would not then try to switch that part of their portfolio into assets that earned higher returns, such as loans. That is implausible.

Rapier 03.10.19 at 12:45 am

““In the United States, the huge increase in the monetary base occurred both because of the financial crisis and because the Federal Reserve started paying interest on bank reserves in excess of the minimum requirement. The Fed’s rate has exceeded what banks could receive from other safe short-term investments.”

I despair. The monetary base is the Feds balance sheet.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BOGMBASE

Bank reserves, ‘excess’ or not, are related and strongly influenced by the base but not totally determined by it. The Fed created deposits after all with their purchases of Treasury and MBS paper. Plain old bank credit also creates deposits. Here are the ‘excess’ reserves.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/EXCSRESNS

At the absurd 2.4% the Fed is now paying that works out to let’s say $10bn/quarter to banks, mostly the giants. So the Fed created much of those reserves, ie. money, and now is paying the banks billions for having it. The word for this is a racket, but I digress.

Oh forget about it. The last thing anyone wants to hear about when discussing monetary policy is money

John Quiggin 03.10.19 at 7:20 am

@30 JW Mason is excellent as usual and confirms my view: MMT (in its correct form) is standard Keynesianism. It’s viewed from a different perspective and most advocates have expansionist prior beliefs about the scope for stimulus, but there is no fundamental difference.

The primary problem is the MMT fans who interpret the theory as meaning “we can have all the nice things we want without any of those nasty taxes). The secondary problem is the unwillingness of some leading MMTers to set their fans straight on these errors.

Kristjan 03.10.19 at 7:51 am

Kurt Schuler said:

“Kristjan, reserves and loans are competing assets. The mix that banks hold depends on their judgment of risk versus return. Imagine that instead of paying interest on excess reserves, the Fed started charging a penalty. Your statement implies that banks would not then try to switch that part of their portfolio into assets that earned higher returns, such as loans. That is implausible.”

They are not competing assets unless household loans that banks make are cash loans. If I understand you correctly then your logic implies that if there are cheap excess reserves around then banks would prefer to loan those reserves to households and businesses. But if FED pays interest on those excess reserves then they are not available to make business and household loans. This is exactly what MMT rejects and not only MMT. Loans are made without touching those excess reserves, the thing that matters about the reserves is price(interest rate). What is the price that banks can get the reserves at? The reason FED is paying interest on excess reserves is that It wants to set the FED funds rate on target. It cannot do it normally by buying and selling government securities because It has pumped so much excess reserves to the system during QE, unless It wants to reverse the QE.

So you could say that FED hiked overnight rate and that is why loans were not made to households but the quantity of reserves is not important. There could not have been any excess reserves and FED could have conducted interest rate setting in a usual way(by buying and selling government securities) and functionally It would have been exactly the same. Banks create deposits by making loans, the deposits don’t come from anywhere.

bob mcmanus 03.10.19 at 8:13 am

MMT (in its correct form) is standard Keynesianism.

Without committing to any side in the MMT debates, I would suggest that “standard Keynesianism” ain’t what it used to be. Too monetarist, which is the point.

There was a time, oh about three decades when Keynesianism was openly a Utopian vision (Economic possibilities for our grandchildren) competing with the most radical Utopian visions. Grand programs were enacted, great structures built, hopes kindled and often fulfilled. Tragic mistakes were made, instabilities and disequilibriums were common.

There has been way too much complacency and lack of ambition among center-left economists since the 70s. Frankly they strike me as defensive and frightened of the neoclassicals and austerians. Now DeLong has ceded the crazy to his left when he should be pushing the center toward experimentalism and risky ventures.

And part of the point of MMT is to push back against economic defeatism implied in the “nasty taxes” (which can’t get passed). MMT will make them, if nothing else, at the point of hyperinflation or global depression pass some freaking taxes. The Right sure is willing to gamble with other people’s money.

Kristjan 03.10.19 at 8:29 am

Kurt Schuler:

“Kristjan, reserves and loans are competing assets. The mix that banks hold depends on their judgment of risk versus return. Imagine that instead of paying interest on excess reserves, the Fed started charging a penalty. Your statement implies that banks would not then try to switch that part of their portfolio into assets that earned higher returns, such as loans. That is implausible.”

Banking system as a whole cannot get rid of reserves unless government taxes them away or fed drains them (sells government securities from its portfolio).

Kristjan 03.10.19 at 10:50 am

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2355178

“In contrast to standard textbook renderings of an exogenous money supply and money multiplier, Post Keynesian economists contend that money supply is statistically endogenous to the demand for credit. Empirical evidence based on analysis of monthly U.S. data from 1971 to 2008 substantiates the endogenous money hypothesis. Results from Toda and Yamamoto Granger-causality tests demonstrate unidirectional Granger-causality from commercial bank lending to the monetary base and money supply. Bidirectional Granger-causality between money supply and nominal income also exists. These results are relatively robust to variations in monetary aggregates, such as broader measures (e.g. M3 and M4) and weighted-average indexing (e.g. Divisia).”

Kristjan 03.10.19 at 12:14 pm

@30 the link you provided:

“What reason do we have to believe that an elected government that was free to set the budget balance at whatever level was consistent with price stability and full employment, would actually do so? This is where the real resistance lies”

Is that where the resistance lies? Not really in NAIRU, not in loanable funds etc? Those are concepts for masking their fears?

If so then I have to ask that why should we have democracy at all? Why not let unelected officials to decide our foreign policy, educational policy etc? Who is to say that our democratically elected representatives are not going to screw up in those areas? Bad government choices affect us all, what is so special about the economy that unelected officials are suppose to tell us fairy tales?

Comments on this entry are closed.