“Ye higher men, free the sepulchres, awaken the corpses! Ah, why doth the worm still burrow? There approacheth, there approacheth, the hour, — — There boometh the clock-bell, there thrilleth still the heart, there burroweth still the wood-worm, the heart-worm. Ah! Ah! THE WORLD IS DEEP!”

– F. Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra

So I ran another of those Twitterpoll thingies and it was decisive. Seven people voted, including one rubbernecker who likes to watch. And so the people have spoken! So I’m back to explaining jokes, like before. (Racking numbers like those, I should start a Nietzsche joke explanation Substack. Which is to say: webcomics is hard, kids. Like the King said, ‘comics will break your heart.’)

The questions was basically: what’s up with pages like this?

If you’ve visited my fine site, you are aware I’ve opted for a handsome vermiform motif on the landing page. Observe the elegance of the design! Suggestiveness of the background!

If you’ve visited my fine site, you are aware I’ve opted for a handsome vermiform motif on the landing page. Observe the elegance of the design! Suggestiveness of the background!

And the tag:

“Ye have made your way from worm to man, and much within you is still worm.” That’s what Z says to the townsfolk, in Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke. (By the by, what should I name my little winged worm guy? I haven’t named him.)

The more famous bit from Z’s speech here is the ‘man suspended between ape and superman’ bit (which is, of course, immortalized – for better or worse – in “2001”.)

But what of worms? OK, let me quote a bit more:

Ye have made your way from the worm to man, and much within you is still worm. Once were ye apes, and even yet man is more of an ape than any of the apes. Even the wisest among you is only a disharmony and hybrid of plant and phantom. But do I bid you become phantoms or plants?

That’s wild! I should do a page for that one, Z bothering some bystander, maybe a goggle-eyed kid. “Do I ask you to become a phantom or a plant? DO I?” But hold off on phantom-or-plant just one second.

In what way(s) are we worm-like, for Nietzsche? And why is it funny?

I think the funny of it is caught well by one of my favorite Nietzsche jokes. The bit from Genealogy of Morals, First Essay, in which he is riffing about English psychologists.

These English psychologists—whom we have to thank, as well, for the sole attempts thus far to historicize the genesis of morality—are themselves no small riddle for us; I confess, in fact, that as riddles in the flesh they body forth something more substantial, above and beyond their books—they themselves are interesting! These English psychologists—what do they really want? One finds them always, by accident or design, at the same work, namely that of pushing the private parts of our inner world into the foreground, and, by the same token, seeking after that which is indeed the effective, leading, decisive root of our development just where the intellectual pride of man is most loath to admit it … What is it that always drives these psychologists in just this direction? …. I am told they are just old cold, boring frogs who creep and hop around, on and into human beings, as if here they were truly in their element, namely, a swamp. I don’t want to think it; furthermore, I don’t think it; and if one may be permitted to wish where one cannot know, I wish with all my heart it may be quite the opposite with them—that these explorers and microscopists of the soul are at bottom brave, magnanimous and proud beasts who know how to hold tight the reins on their hearts and their pain, who have conditioned themselves to sacrifice all desirability to truth, to every truth, even plain, harsh, contrary, unsightly, unchristian, immoral truth … For there are such truths!

Furthermore, as E.B. White writes: “Humor can be dissected, as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the pure scientific mind.” Which redoubles the frog-related humor of it.

OK, one more note about the comedy origins of this little project of mine.

In Comic Relief: Nietzsche’s Gay Science, Kathleen Marie Higgins writes: “My thesis, straightforwardly, is that in this work Nietzsche often aimed to be funny.” This is The Gay Science she’s writing about. Now, first, I hope everyone knows there are funny bits in The Gay Science. If you can’t find several things in there that are faintly funny, that’s definitely a you problem. But Higgins is arguing a bit more than that. But, without getting into that, the idea of writing a scholarly book the thesis of which is that another book aimed to be funny is … inherently hilarious. (I won’t explain why.)

This is sort of why I thought it was a philosophically sound plan to retell Nietzsche in a way that just makes it funnier. Period.

Anyway, Nietzsche is interested in psychology, which he finds funny, and psychologists, who are funny. And I think he finds it funny that he finds all this funny (when some others don’t.)

But frogs aren’t worms!

A fair point. But frogs are kind of gross, and dissected frogs have insides that are grosser. So the figure of a self-dissecting frog, as noble science hero, self-pinned to the board, is … something.

Now worms! Worms are not just in the ground but in fruit. Nietzsche often favors ripe fruit metaphors for ideas. By extension, for persons. His own slow growth and fruiting is like that of a tree. (So you are starting to get plant-or-phantom. Post-Christians who talk themselves into fatalism may feel it.)

Now worms! Worms are not just in the ground but in fruit. Nietzsche often favors ripe fruit metaphors for ideas. By extension, for persons. His own slow growth and fruiting is like that of a tree. (So you are starting to get plant-or-phantom. Post-Christians who talk themselves into fatalism may feel it.)

From Genealogy, the Preface:

“Rather with the necessity with which a tree bears its fruit, so do our thoughts, our values, our Yes’s and No’s and If’s and Whether’s, grow connected and interrelated, mutual witnesses of one will, one health, one kingdom, one sun — as to whether they are to your taste, these fruits of ours? — But what matters that to the trees? What matters that to us, us the philosophers?”

Will the way, will the worms. From Human, All Too Human, §353:

“Worms. — The fact that an intellect contains a few worms does not detract from its ripeness.”

Nietzsche associates wormy-thinking, more specifically, with skepticism, and a burrowing through to get beyond. From Daybreak, §477:

“Freed from Scepticism. —

A. Some men emerge from a general moral scepticism bad-tempered and feeble, corroded, worm-eaten, and even partly consumed — but I on the other hand, more courageous and healthier than ever, and with my instincts conquered once more. Where a strong wind blows, where the waves are rolling angrily, and where more than usual danger is to be faced, there I feel happy. I did not become a worm, although I often had to work and dig like a worm.

B. You have just ceased to be a sceptic; for you deny!

A. And in doing so I have learnt to say yea again.”

I could quote more in the same vein, also thoughts about worms of remorse and guilt and how they do not breed in prison, only in prisons of the mind of a more rarified sort. But let me finish this post with a worm-related thought – of thoughts-and-drives-as-polyps. Polyps are like worms. From Daybreak §119:

Experience and Invention. — To however high a degree a man can attain to knowledge of himself, nothing can be more incomplete than the conception which he forms of the instincts constituting his individuality. He can scarcely name the more common instincts: their number and force, their flux and reflux, their action and counteraction, and, above all, the laws of their nutrition, remain absolutely unknown to him. This nutrition, therefore, becomes a work of chance: the daily experiences of our lives throw their prey now to this instinct and now to that, and the instincts gradually seize upon it; but the ebb and flow of these experiences does not stand in any rational relationship to the nutritive needs of the total number of the instincts. Two things, then, must always happen: some cravings will be neglected and starved to death, while others will be overfed. Every moment in the life of man causes some polypous arms of his being to grow and others to wither away, in accordance with the nutriment which that moment may or may not bring with it. Our experiences, as I have already said, are all in this sense means of nutriment, but scattered about with a careless hand and without discrimination between the hungry and the overfed. As a consequence of this accidental nutrition of each particular part, the polyp in its complete development will be something just as fortuitous as its growth.

To put this more clearly: let us suppose that an instinct or craving has reached that point when it demands gratification, — either the exercise of its power or the discharge of it, or the filling up of a vacuum (all this is metaphorical language), — then it will examine every event that occurs in the course of the day to ascertain how it can be utilised with the object of fulfilling its aim: whether the man runs or rests, or is angry, or reads or speaks or fights or rejoices, the unsatiated instinct watches, as it were, every condition into which the man enters, and, as a rule, if it finds nothing for itself it must wait, still unsatisfied. After a little while it becomes feeble, and at the end of a few days or a few months, if it has not been satisfied, it will wither away like a plant which has not been watered. This cruelty of chance would perhaps be more conspicuous if all the cravings were as vehement in their demands as hunger, which refuses to be satisfied with imaginary dishes; but the great majority of our instincts, especially those which are called moral, are thus easily satisfied, — if it be permitted to suppose that our dreams serve as compensation to a certain extent for the accidental absence of “nutriment” during the day. Why was last night’s dream full of tenderness and tears, that of the night before amusing and gay, and the previous one adventurous and engaged in some continual obscure search? How does it come about that in this dream I enjoy indescribable beauties of music, and in that one I soar and fly upwards with the delight of an eagle to the most distant heights? These inventions in which our instincts of tenderness, merriment, or adventurousness, or our desire for music and mountains, can have free play and scope — and every one can recall striking instances — are interpretations of our nervous irritations during sleep, very free and arbitrary interpretations of the movements of our blood and intestines, and the pressure of our arm and the bed coverings, or the sound of a church bell, the weathercocks, the moths, and so on. That this text, which on the whole is very much the same for one night as another, is so differently commented upon, that our creative reason imagines such different causes for the nervous irritations of one day as compared with another, may be explained by the fact that the prompter of this reason was different to-day from yesterday — another instinct or craving wished to be satisfied, to show itself, to exercise itself and be refreshed and discharged: this particular one being at its height to-day and another one being at its height last night. Real life has not the freedom of interpretation possessed by dream life; it is less poetic and less unrestrained — but is it necessary for me to show that our instincts, when we are awake, likewise merely interpret our nervous irritations and determine their “causes” in accordance with their requirements? that there is no really essential difference between waking and dreaming! that even in comparing different degrees of culture, the freedom of the conscious interpretation of the one is not in any way inferior to the freedom in dreams of the other! that our moral judgments and valuations are only images and fantasies concerning physiological processes unknown to us, a kind of habitual language to describe certain nervous irritations? that all our so-called consciousness is a more or less fantastic commentary of an unknown text, one which is perhaps unknowable but yet felt?

What follows is a personal anecdote about Nietzsche. But never mind that. The psychology is interesting, and that Nietzsche puts it forth.

What follows is a personal anecdote about Nietzsche. But never mind that. The psychology is interesting, and that Nietzsche puts it forth.

First, Nietzsche would have understood the internet very well. The way in which internet addiction is a sort of polyp-feeding frenzy. True!

Second, it’s a kind of Schopenhauerianism, but translated into a less metaphysicalized, more psychologized idiom. The self is sort of a polyp colony, and consciousness is polyps sort of popping up out into the light. The worm as Will and Representation! The genealogy of morals told as a tale of worm impulses grown social and increasingly sophisticated?

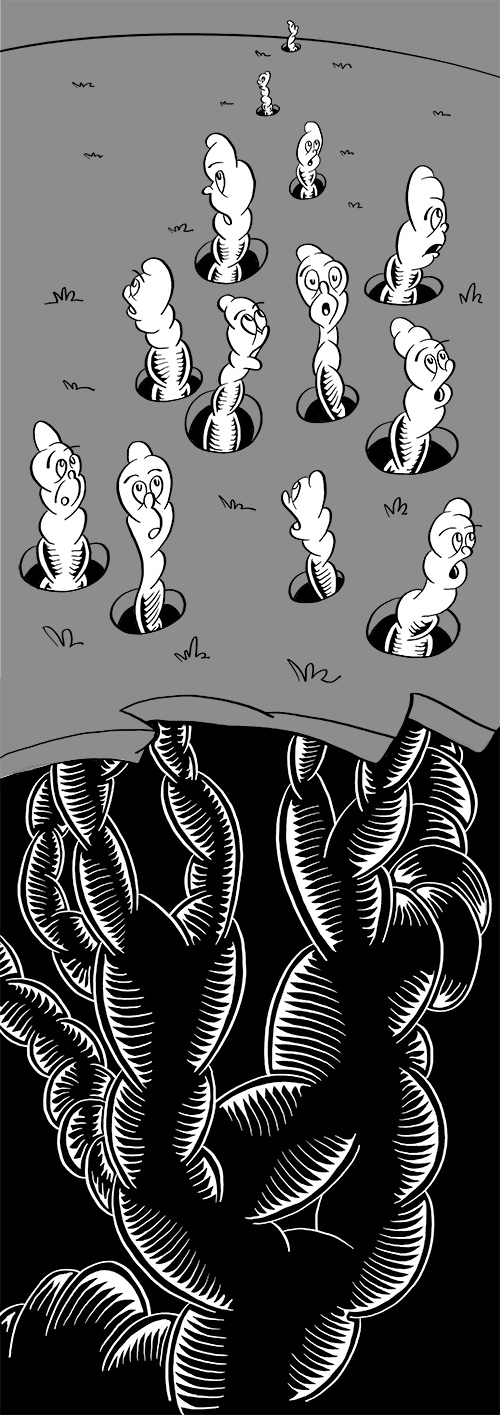

Anyway, I think Zarathustra on worms – and snakes: don’t forget biting the heads off snakes – may go with this polypolypous picture Nietzsche has of the ‘soul’. The obvious question being: if that’s who we are, in what sense can we aspire to transcend that? (Can the worm turn back on itself?)

So that’s sort of why I make Z riff on worms to the townsfolk: the image of a flicked worm ‘overcoming’, as an ideal image of progress. The overcoming of morality?

Thank you for your interest and continuing support for me sort of spelling out the reasons for my jokes. (I’m thinking of writing a book, you see.)

{ 16 comments }

Neville Morley 04.21.21 at 6:22 am

Is this where Alan Moore got his “planarian worms eating one another as vector of consciousness†thing in Swamp Thing?

John Holbo 04.21.21 at 8:39 am

I … never thought of that.

notGoodenough 04.21.21 at 9:41 am

“Humor can be dissected, as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the pure scientific mind”

I think I would disagree a little with White – sometimes the dissection (if carried out with sufficient gusto) can lend a meta-irony which is truly delightful for those of us who appreciate absurdities – the over-explanation of the joke becomes the joke (

turtlesjokes all the way down).“Thank you for your interest and continuing support for me sort of spelling out the reasons for my jokes” (I’m thinking of writing a book, you see.)

Even though I only know enough to know I know nothing, I´m enjoying these posts – I´d always associated envy more than humour with Nietzsche, and this is a fun take from a different angle than I´ve seen before (not that I´ve ever explored these sorts of topics much).

I think – whether one´s interests lie with the classical, the Hegelian, logical positivism, or one is merely tinkering with the metaphorical sheep dip – it is important to “always look on the bright side”.

Gareth Wilson 04.21.21 at 10:24 am

There was an experiment in 1960 that seemed to show flatworms acquiring memories from eating trained flatworms. That’s probably where Alan Moore got it from. Larry Niven used the idea in A World Out of Time. Unfortunately the results weren’t reproducible.

Lawrence A Schuman 04.21.21 at 4:57 pm

The frog one reminds me of Erol Otus.

oldster 04.21.21 at 5:47 pm

“(By the by, what should I name my little winged worm guy? I haven’t named him.)”

“Vermicelli” looks enough like vermis caeli (sc. the worm of heaven) to be funny.

SusanC 04.21.21 at 5:58 pm

@4. I remembered the experiment, but couldnt remember where I’d read it, Probably A World Out of Time.

Its a bad state of affairs if you cant remember whether you read it in an actual peer reviewed journal, or a Larry Niven novel.

Dr. Hilarius 04.21.21 at 6:43 pm

I recall the coverage of the planaria memory experiment. Coverage of the result being discredited was of less interest to the mass media and many people still believe the original work to be valid.

Gareth Wilson 04.21.21 at 10:38 pm

Charlie Stross said that A World Out of Time has an unusually large number of discredited ideas for an SF novel. “Memory RNA”, a global totalitarian state, interstellar ramjets…

KT2 04.22.21 at 2:25 am

Worm names…

Kermes.Â

Kermes S. Kancel.

Patraeus (see sugar glider below)

Kermes J J Aloenz (“must be alones” “2 middle names jones”)

Werner Ambul – a funambulist (‘Wern’ to friends)

I like the short names for worm gods below tho.

Gordian Worms

Introduction

Gordian worms belong to a small phylum, the Nematomorpha: a name that means ‘form of a thread’. Their habit of writhing and contorting themselves into knots, with one or more worms tangled together, accounts for their common name, ‘Gordian’ Worm. This is after Gordius, King of Phrygia, who tied an intricate knot and declared that whoever untied it should rule Asia. Alexander the Great cut the Gordian knot with his sword.”

https://australian.museum/learn/animals/worms/gordian-worms/

“THE GOD OF THE WINGED WORM

“Complete in itself, this story is part of a forthcoming novel, The Weak and the Strong

https://classic.esquire.com/article/1946/3/1/the-god-of-the-winged-worm

“The Meaning of Hermes

“The etymology of quercus coccifera, the specific name ‘coccifera,’ is related to the production of red cochineal (crimson) dye and is derived from Latin, coccum; which was from Greek κὀκκος, the kermes worm. The Latin -fera means ‘bearer’. Hence, instead of Lucifer the light bearer, we have kermes (worm) the purple bearer.

“The symbol of Hermes also has the word ker. In Greek, his symbol is called the kerykeion (ker-y-kei-on), and today it is known primarily by the Latin word ‘caduceus,’ with the two serpents/kermes/worms intertwined around a winged staff.”

https://gnosticwarrior.com/the-meaning-of-hermes.html

“Worm Gods

– Akka, the Worm of Secrets (Deceased)

– Eir, the Keeper of Order

– Ur, the Ever-Hunger

– Xol, Will of the Thousands (Incapacitated)

– Yul, the Honest Worm

https://www.destinypedia.com/Worm

The Conqueror Worm

BYÂ EDGAR ALLAN POE

[last verse]

“Out—out are the lights—out all!  Â

And, over each quivering form,Â

The curtain, a funeral pall,Â

Comes down with the rush of a storm,  Â

While the angels, all pallid and wan,  Â

Uprising, unveiling, affirmÂ

That the play is the tragedy, “Man,â€Â  Â

And its hero, the Conqueror Worm”

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48633/the-conqueror-worm

You could take On Beyond Zarathustra anywhere, even a trip downunder, via language:- “…Â for it had been announced that a rope-dancer [sugar glider!] would give a performance.”…

“Sugar glider Translation On Other Language:

…

…” The scientific name, Petaurus breviceps, translates from Latin as “short-headed rope-dancer”, a reference to their canopy acrobatics”

https://translation.babylon-software.com/english/Sugar+glider/

And any chance of working this work into OBZ?

funambulist (n.)

“tightrope-walker,” 1793, coined from Latin funis “a rope, line, cord,” + ambulare “to walk” (see amble (v.)). Earlier was funambulant (1660s), funambule (1690s from Latin funambulus, the classical name for a performer of this ancient type of public entertainment), and pseudo-Italianfunambulo (c. 1600).

https://www.etymonline.com/word/funambulist

Twelve-Winged Worm

…”  differentiated into two smaller parts, which can be moved independently from each other, because the joint of a wing has divided into six joints, one for each wing. The wings now even have different functions: The first four wings (first two pairs) are used for active movement. The next six wings (next 3 pairs) are bigger and are mostly used for gliding in the air. The last pair of wings is used for navigation, so that they can decide the course directly. Due to this active style of flying, they have to burn a lot of oxygen,. ..”

https://sagan4alpha.miraheze.org/wiki/Twelve-Winged_Worm

And who could forget…

“Lowly Worm

“Lowly Worm is a fictional character created by Richard Scarry; he frequently appears in children’s books by Scarry, and is a main character in the animated series The Busy World of Richard Scarry and Busytown Mysteries”…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lowly_Worm

I will introduce my teenager to OBZ. Thanks.

ecce cur 04.22.21 at 10:11 am

You should name the winged worm “Menocchio” in honor of the Italian peasant from Ginzburg’s ‘The Cheese and the Worms’. Regarding his heretical cosmology for which he was executed, he is reported to have said, “all was chaos, that is, earth, air, water, and fire were mixed together; and out of that bulk a mass formed – just as cheese is made out of milk – and worms appeared in it, and these were the angels.” A kindred spirit to our dear Friedrich.

Regarding philosophy and jokes, Norman Malcolm wrote in his memoir: “It is worth noting that Wittgenstein once said that a serious and good philosophical work could be written that would consist entirely of jokes (without being facetious).” Good old Ludwig, the Austrian cut up.

Bill Benzon 04.22.21 at 12:05 pm

On dissecting humor, & FWIW, Jerry Seinfeld is fond of saying that jokes are finely calibrated machines. And he just loves examining them and taking them apart.

& he has written a couple of books. In his most recent one he lists every joke he’s ever told – he keeps a record of them on the yellow pads he uses to think on. Don’t think there are any explanations in it, though.

Jake Gibson 04.22.21 at 1:01 pm

You need to tell the religionists that a global totalitarian state has been discredited.

Fcb 04.22.21 at 9:42 pm

You should name him “Oroubonot”.

John Holbo 04.23.21 at 12:38 am

Thank you for the worm names. I shall consider.

KT2 04.23.21 at 3:46 am

You never know. Seth may option OBZ.

“Seth Rogen and the Secret to Happiness

. …

“These are gags we started to actually draw,†he said.

Working with an illustrator, Rogen and Goldberg had completed what was in essence a digital flip book diagraming every scene in “Escape.†“We’re literally storyboarding every second of the movie,†Rogen said. One open-ended, three-word gag I’d seen in a list from May 2019 — centered delightfully on something you could buy in a hardware store — had been storyboarded into an elaborate action sequence. Rogen showed it to me frame by frame, narrating as he went. “She’s trying to go from there to there … these guys are chasing her. … †His finger tapped the right arrow. “She grabs that guy, he’s falling, bam, whoop!â€

Even in flip-book form, the scene was funny. “We need to know if these jokes are working, and if the timing is right,†Rogen said, “and you can’t do a table read and see if people laugh or not, because that would be me saying, like, ‘He throws the thing, it bounces off the door, it hits him in the face.’†He laughed. “We need to be able to see that!â€

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/20/magazine/seth-rogen.html

Comments on this entry are closed.