One of my favorite metasciences lines is: “Does anyone look around and say…things are going great, I just think we need MORE PAPERS?”

Obviously, we all want more scientific progress, better evidence, broader scope — but I don’t think that this is best accomplished by churning out more of these fancy peer-reviewed pdfs. Indeed, our systems of peer review and knowledge evaluation are breaking down under the strain. Everyone is under pressure to produce more and more papers earlier and earlier in their careers.

The situation is accelerating with LLMs. The cost of producing these pdfs continues to decline, and as long as the demand for the pdfs stays strong, we should expect the supply to increase. Everyone agrees that this is a problem.

Well, almost everyone.

If this were a well-functioning economy, demand would eventually be sated. The for-profit corporations running the academic journals at the heart of our enterprise are more than happy to “buy” every single one of these pdfs — because they’ve figured out how to “buy” them from us using our own money.

This “AI revolution” is coming on the tails of another revolution in academic publishing — the move away from subscription-based academic journals to individual articles published “Open Access” in exchange for Article Processing Charges (APCs).

Under the old model, academic libraries paid for printed academic journals to be delivered so that professors and grad students could read them. This was a high-margin business, but there was still a verifiable service being rendered by the publishers: someone had to format, archive and deliver the physical pieces of paper. With the internet, the dead trees became vestigial; the subscriptions were to the online versions of these journals, but they were sold as a package: the libraries had to subscribe to an entire publishers’ catalogue in order for their academic institution to remain competitive.

But this model wasn’t incentive-compatible. Once an academic has published an article, they want it to be read by as many people as possible. And the internet makes it very easy for these pdfs to slip through paywalls. Just like streaming music allowed the big labels to maintain market dominance, the publishing corporations figured out a new model: Open Access. Who could possibly be against Open Access!

Some journals became entirely Open Access, moving 100% to the Article Processing Charge model where the authors pay up front and then the pdf is put on the internet for free. The model comes out of the hard sciences — like all metascience reforms, it makes the most sense in the context in which it was developed. Natural sciences have to get massive grants to actually conduct the research, so the cost of the APC is a rounding error. For social scientists and especially humanities disciplines where the work costs very little or nothing, the APCs represent a massive cost. Even worse, some of the journals are “double dipping” by offering individual authors the right to publish their work open access in exchange for an APC but still charging subscription fees to access the rest of the articles published in those journals — the so-called “hybrid model.”

It’s worth noting that none of this money is necessary. Academics could decide to cut out for-profit journals entirely, to put our own pdfs online ourselves. The Journal of Machine Learning Research did it:

The journal was established as an open-access alternative to the journal Machine Learning. In 2001, forty editorial board members of Machine Learning resigned, saying that in the era of the Internet, it was detrimental for researchers to continue publishing their papers in expensive journals with pay-access archives. The open access model employed by the Journal of Machine Learning Research allows authors to publish articles for free and retain copyright, while archives are freely available online.

The journal I co-founded does it:

JQD:DM is a diamond access, double-blind peer-reviewed scholarly journal hosted on the University of Zurich’s HOPE platform. We do not require article processing charges (APCs), and articles are available to access for free (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

The journal publishes quantitative descriptive social science. It does not publish research that makes causal claims.

The Journal of Trial and Error does it — and they even published a handy guide for setting up your own diamond open access journal online.

But the absurdity of for-profit academic publishing has been obvious for decades. Academics are complacent — and there enough academics in pivotal positions getting a few crumbs from these academic publishers — so the system perpetuates itself. Fine. These are messy, complex systems and it’s naive to think that changing them will be easy.

Which actors want more pdfs in circulation? The ones getting paid $1,500 or $3,450 or $12,290 a pop.

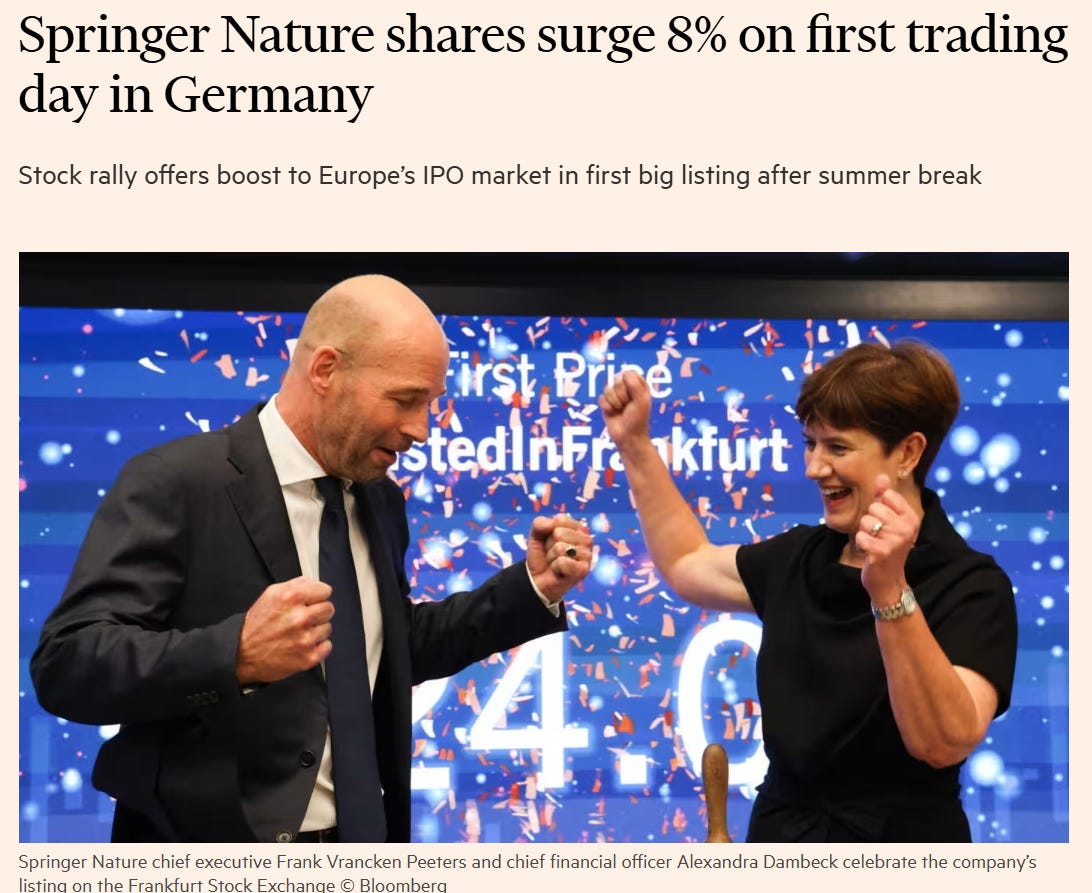

But the APC model means that academic journals are aiming for a future in which we’re swimming in LLM garbage. Which actors want more pdfs in circulation? The ones getting paid $1,500 or $3,450 or $12,290 a pop. What an astonishing business model, as the FT reports: Nature is the journal commanding that eye-watering sum.

The for-profit journals don’t care about academic progress. They care about….profit. They literally cannot care about anything else, thanks to the doctrine of maximizing shareholder value in a context of private equity and hostile corporate takeovers. If they try to care about anything but profit, someone can come along and take them over and make them more profit-focused, as Dan Davies documents in his excellent book earlier this year.

Peeters and Dambeck say: hooray for Open Access!!

A recent publication titled “The oligopoly’s shift to open access” provides some hard numbers:

We aim to estimate the total amount of article processing charges (APCs) paid to publish open access (OA) in journals controlled by the five large commercial publishers (Elsevier, Sage, Springer Nature, Taylor & Francis, and Wiley) between 2015 and 2018…we estimate that globally authors paid $1.06 billion in publication fees to these publishers from 2015–2018. Revenue from gold OA amounted to $612.5 million, and $448.3 million was obtained for publishing OA in hybrid journals. Among the five publishers, Springer Nature made the most revenue from OA ($589.7 million), followed by Elsevier ($221.4 million). (emphasis mine)

The annual revenue from Open Access has surely skyrocketed in the six years since the data from this study concluded.

Academia is far smaller and more federal than “the market.” People literally built this thing. In order to make it better, we should do metascience: we should use our tools to figure out what we want to do, and then use our institutions to actually do that. The mystical complexity of “the market” as some emergent phenomenon just doesn’t apply here.

Academic publishing is yet another example of the artificial. We’ve let the epiphenomenal outputs of doing science, of generating knowledge, of thinking, stand in for the phenomenon itself. The idea that using “AI” as a shortcut for human work will produce a de-skilling of new generations is now well-understood. But this is just one example of the more general cybernetic maxim that “You can never do one thing.”

When we write and publish a peer-reviewed paper, there is work going in at every stage. The fact that there’s a human coordinating all of the action means that there’s a human with a map of the overall project in their head. When we divide and sub-divide all the processes that go into the project — whether through human delegation or with “AI” — we lose the guarantee of an integral, individual human brain with the overall map of the project in it. The future of AI-powered social science is one where every scientist is a middle manager.

Academia isn’t just producing pdfs. The more we throw ourselves into this artificial little world where Springer-Nature gets $12290 a pdf, the less effective academics become at all of the other functions we serve in society.

The future of AI-powered social science is one where every scientist is a middle manager.

Now, the looming disruption promised by LLMs can be productive if we collectively try to address the crisis. The status quo really is incoherent and sclerotic. The most likely response to the flood of pdfs is a further retreat into elite networks — being “in the room” will become even more important if that’s something AI can’t do. This is far from the optimal outcome. We should think bigger, about how LLMs (or even just the internet) allows us to re-organize scientific knowledge production.

One thing we definitely need to do, though, is work. We need to read and write and think about things. The “Open Science” response is to create artificial representations of those activities in order to make them auditable, to make them visible to outsiders, to make academics therefore rankable. This means throwing away the very thing that makes academia distinct. Academic freedom doesn’t just mean getting to say whatever we want — it’s not just this freedom to. It’s the freedom from the systems of control that continue to creep into every area of human endeavor.

It was one thing when the for-profit academic journals extracted ridiculous profit margins from the work done by volunteers and financed by taxpayer dollars. As communication technology changes and they scrambled to adapt their business model, the actual practice of science has shifted as well. I know that serious scientists don’t wanna hear it, but the scientific knowledge we produce is obviously and strongly structured by our institutions. The tighter the labor market and the more artificial the metrics we use to evaluate each other (the farther from actually reading the work and subjectively evaluating its quality), the more power these institutions have.

And now these for-profit corporations are setting the agenda for how LLMs will be incorporated into scientific practice. They are very clearly aiming towards a world in which text is commodified, greater and greater volumes of meaningless and unread text circulating for the sole purpose of individual academic careers — where they get $1,500 a pop. Hence the only guidelines for the use of LLMs in academic publishing put out by Springer amount to: “Let’er rip.”

The big worry in the research community is that students and scientists could deceitfully pass off LLM-written text as their own, or use LLMs in a simplistic fashion (such as to conduct an incomplete literature review) and produce work that is unreliable….

That’s why it is high time researchers and publishers laid down ground rules about using LLMs ethically. Nature, along with all Springer Nature journals, has formulated the following two principles:

The fear is that LLMs might threaten “Transparent Science,” per the title, or that LLMs might produce work that is “unreliable.” So they say that in order to use LLMs “ethically,” they require that you….just say that you used LLMs. That’s it. Otherwise go nuts. Don’t worry about the institutions of knowledge production and verification — let’s just get as many pdfs circulating as we possibly can.

Anyone talking about “The Ethics of LLMs” and scientific publishing is trying to sell you something—or, in the case of Springer Nature, trying to buy something from you with your own money.

If the ethical questions are individual rather than systemic or collective, the questions are irrelevant.

{ 14 comments }

William D'Alessandro 11.08.24 at 7:34 pm

Great piece — the points about OA and the impending flood of LLM trash seem obviously right and are very worrying, and the only solution may be to keep beating each other over the head with the diamond OA model until it spreads more widely. Another encouraging example is the political philosophy journal Free & Equal, launched this fall by the former editors of Philosophy & Public Affairs in response to pressure from Wiley to publish more (OA-fee-generating) articles.

But also — and maybe this is a weird personal idiosyncrasy — I do wish there were more papers published on the topics I work on. Not because I’d aim to read them all, and not because I think the median published paper is all that amazing. But I learn at least one useful thing from almost every piece that makes it to print (even the dead-wrong ones), and every day I think of topics which I’ll never have time to write about, but which I’d be happy to know that someone did. I find it surprising that many others feel differently.

Probably this is in part a humanities luxury — I can spend 20 minutes on a paper and have a pretty good idea what I think is true, interesting and useful about it. But in the sciences this is often much less obvious and legible, and in some fields your prior on “this is a totally fake result engineered to look convincing to someone who spent 20 minutes on it” has to be pretty high.

Alex SL 11.08.24 at 8:44 pm

Yes, organising things as for-profit corrodes everything. However, the statement the publishing corporations figured out a new model: Open Access is ahistorical to me. As I experienced it as an extremely skeptical observer who feels he has since been completely vindicated by his skepticism, the push for open access came from the community. People were understandably fed up with for-profit publishers but latched onto a pseudo-solution that solved absolutely nothing. It merely shifted the problem from under-resourced colleagues unable to access literature, which at least can be overcome easily by sending a reprint request, to under-resourced colleagues unable to publish, which cannot be overcome.

All the while, the for-profit publishers get fatter on article processing charges, as outlined in the post. But they did not ‘figure this out’, they merely happily adopted the new model after and because large parts of the academic community advocated for it.

David Mitchell 11.08.24 at 11:35 pm

A related area in the academic world where open access would be helpful is textbooks. Textbooks are a substantial part of the cost of getting a degree, in particular in the sciences and engineering. In recent times there is a trend with textbooks having an online access part. This is often linked to online quizzes. This trend eliminates the reuse of textbooks by other students and prevents them from economizing by buying used. Going to online open textbooks would help students save money and I believe result in better quality. It would also open up areas on knowledge to the general population.

There are areas where open access exists. In the world of software defined radio (SDR), there are considerable online open resources and I understand some universities use them in their courses.

DCA 11.09.24 at 10:53 pm

Several things come to mind. As background, I’ve spent my career in a STEM field at an R1 university, and have been on the editorial board of a major journal in my field for 11 years. Said journal is “run” by a society–a nonprofit one, but also one (like many others) that has seen the journal move, via subscriptions, from a loss to a source of income for various things, many of them worthy, such as additional outreach activities. (To see this change at work, try the book “A History of Scientific Journals: Publishing at the Royal Society, 1665-2015” by Fyfe et al [open access]). For decades the machinery for reviewing, printing, and distributing of the journal I’m associated with has been done by a large university press, which at the last contract renewal said, like all the other bidders, that the journal had to move to OA/OPC and drop the hardcopy version.

Am I happy about this? I am not, and would like nothing more than to see Diamond Open Acess. There is a new journal in my field that is following this model, by getting some support from a university press and relying on volunteers for everything from reviewing from copyediting. But the problem I see is, how does this scale? The society journal gets about 1000 submissions a year–and many of them, probably most, need anywhere from some to too much work to be made publishable (we reject about 70%). It is hard enough just to get reviewers–but volunteer copyeditors and formatters?

The other point comes from many years of being on hiring and promotion committees, where nothing has quite the same effect as “last year, published a paper in Nature”. Hence the enormous APC, and also the proliferation of “Nature X” journals–they may not be that selective, but they bear the magic name. In the nature of things, the committee members lack the level of expertise (in whatever relevant sub-sub-field) that the journal can (in principle) bring to bear. So it isn’t just laziness, or being affected by branding, that makes universities outsource their quality control to the journals–but since this is the way things are, change is close to impossible. I was on a faculty committee in 1999 to consider the journal crisis, and I can’t see that anything has changed. (For a good set of views from someone who thought there would be change, and has had to rethink this, see the website of Andrew Odlyzko at https://www-users.cse.umn.edu/~odlyzko/ — he is a very history-minded mathematician.)

TF79 11.10.24 at 2:37 am

Presumably the big dogs looked at what the predatory journals were doing and said “let’s get in on that!”

SusanC 11.10.24 at 10:07 am

One of the questions you might ask is, “who, if anyone, is evaluating whether the research is any good?”

In the sciences, at least, we might be moving the quality assessment to the grant making g bodies…

You write a grant proposal

Reviewers appointed by funding body review your proposal. (QA happens here)

They give you the money (or don’t )

You do the research

You write it up

Online journal publishes it, because you pay them out of the money you got at step (3). QA does not happen here; publisher publishes whatever you pay them to publish

So the stuff that gets published at step 6 is the stuff where at step 2, the reviewers were like “yes, this question is interesting g enough it is worth giving these guys a million dollars to go do the experiment”

Karellen 11.10.24 at 10:47 am

Isn’t there also a demand for pdfs from the academic side? Researchers are pressured to produce pdfs to show results from the funding they’ve received, to justify their position, and to advance their careers. And the academic institutions they work for are pressured to produce pdfs to raise their status amongst similar institutions, and to secure future funding from wealthy donors.

You definitely hint at this with

But I think it deserves more significance as a factor in the overall demand for more and more papers, and hence the desire to use LLMs to produce those papers as efficiently as possible, orthogonally to the actual scientific work being done. Yeah, publishers are happy to take advantage of the situation, and are probably encouraging it in whatever ways they can, but I’m not convinced they’re the main driver of the demand?

SusanC 11.10.24 at 3:23 pm

Perhaps surprisingly, I am an advocate of more papers.

Current system causes academics to optimize the metric that is number of papers in top ranked journals / conferences.

There is an alternative view, along the lines of: since the government just paid you over a million dollars to do that experiment, you should properly write up all the interesting results that came out of it, not just the major result that will make it into a top rated journal. The second ranking results too. Metric optimising leads – somewhat – to underpublication.

P.S. “million dollars” sounds like a deliberate made up number – and it is – but, really, isn’t that far off.

SusanC 11.10.24 at 3:36 pm

DARPA Principal Investigators’ Meetings are probably the other side of the optimum. If you’re in the position where you get to go to some of these, you get to hear other PI’s presentations to DARPA along the lines of “here’s what we’ve done so far, please don’t kill our funding”, which covers what they did rather more expansively than what made it into the peer-reviewed literature. I guess what I’d typically want to read lies somewhere between the two.

SusanC 11.10.24 at 3:44 pm

While I’m on this…

European Commission funding: your interim reports are just between you and the project monitoring officer. (For those readers who havent done this, just imagine a cross between your PhD viva and the Inland Revenue auditing your tax return)

DARPA: the other PIs off the same finding tranche are in the audience, listening, (typically, technical questioning only and no grilling on the terms of the contract, financials, schedule overruns)

Alex SL 11.10.24 at 8:01 pm

SusanC,

I find if very difficult to accept giving up peer review as a quality control mechanism, as flawed as it is due to being done my humans. As it is, I know that I can expect an on average higher standard of quality and likelihood of accuracy of papers in a plant systematics journal than of blog posts, and I would like to keep it that way.

DCA,

In a previous but very recent discussion I said that I had never done any copy-editing in tens of publications over my career. In the weeks since, I have for the first time submitted an article to an open source journal that uses a system where the author does the copy-editing themselves. It is, of course, more work for the author but not as much as I expected, especially because they have a clever DOI lookup for literature citations.

But the results, the look and feel of the articles they publish, is definitely less professional than, those of journals published by say, Wiley. Partly I think this is because of all the decisions that have been automated away. For example, every figure or table is placed after the paragraph where it is first cited, whether it looks good there or not.

dk 11.12.24 at 1:28 am

@2

Indeed, open access was pushed by a segment of the scientific community initially against the will of the publishers. I was an academic then, and I was appalled by the idea that I’d have to pay to publish – so much moral hazard! so much neoliberalism! And thus it’s proved to be. On the other hand, when I was young, some very wise people told me that the move to publish physics papers in for-profit journals like Nature was going to create a real problem, and I dismissed that as oldthink. Oops.

KT2 11.12.24 at 5:03 am

“Well, almost everyone.”

“Then came ChatGPT. Suddenly students had a free alternative to the answers Chegg spent years developing with thousands of contractors in India. Instead of “Chegging” the solution, they began canceling their subscriptions and plugging questions into chatbots. Since ChatGPT’s launch, Chegg has lost more than half a million subscribers who pay up to $19.95 a month for prewritten answers to textbook questions and on-demand help from experts. Its stock is down 99% from early 2021, erasing some $14.5 billion of market value. Bond traders have doubts the company will continue bringing in enough cash to pay its debts.”

https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/careersandeducation/how-chatgpt-brought-down-an-online-education-giant/ar-AA1tMKzw

KT2 11.18.24 at 10:55 pm

“This “AI revolution”…

The Murdoch ai market / publishing monsopony / ai investors, are trying to turn academics smarts into commodity training data.

Academics strike? “The Writers Guild spent 148 days on the picket line”?

The image Cory Doctorow places under headline is Murdoch as Sauron. I cant unsee it.

https://i0.wp.com/craphound.com/images/murdoch-ai.jpg

“Harpercollins wants authors to sign away AI training rights

…

“The right to decide who can train a model on your work does you no good unless it comes with the power to exercise that right.

“Rather than campaigning for the right to decide who can train a model on our work, we should be campaigning for the power to decide what terms we contract under. The Writers Guild spent 148 days on the picket line, a remarkable show of solidarity.”

…

https://pluralistic.net/2024/11/18/rights-without-power/#careful-what-you-wish-for

Comments on this entry are closed.