One of my foundational theoretical commitments is that the technology of reading and writing is neither natural nor innocuous. Media theorists McLuhan, Postman, Ong and Flusser all agree on this point: the technology of writing is a necessary condition for the emerge of liberal/democratic/Enlightenment/rationalist culture; mass literacy and the proliferation of cheap books/newspapers is necessary for this culture to spread beyond the elite to the whole of society.

This was an expensive project. Universal high school requires a significant investment, both to pay the teachers/build the schools and in terms of the opportunity cost to young people. Up until the end of the 20th century, the bargain was worth it for all parties invovled. Young people might not have enjoyed learning to read, write 5-paragraph essays or identify the symbolism in Lord of the Flies, but it was broadly obvious that reading and writing were necessary to navigate society and to consume the overwhelming majority of media.

And it’s equally obvious to today’s young people that this is no longer the case, that they will not need to spend all this time and effort learning to read long texts in order to communicate. They are, after all, communicating all the time, online, without essentially zero formal instruction on how to do so. Just as children learn to talk just by being around people talking, they learn to communicate online just by doing so. In this way, digital culture clearly resonates with Ong’s conception of “secondary orality,” as having far more in common with pre-literate “primary oral culture” than with the literary culture rapidly collapsing, faster with each new generation.

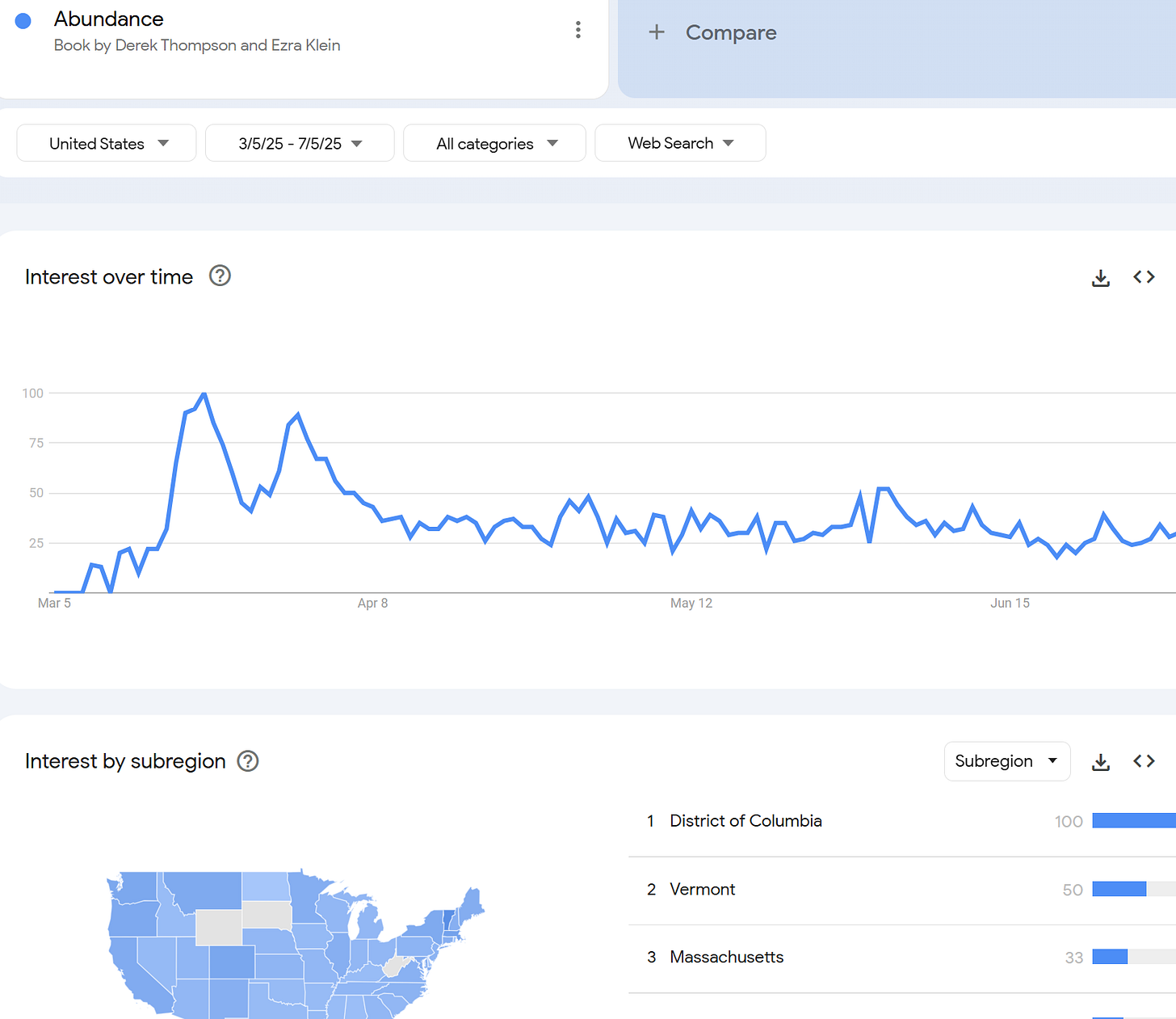

This collapse is increasingly obvious; recent high-profile midbrow examples include Chris Hayes’ book (best experienced through the medium of an Ezra Klein podcast) and Derek Thompson’s report on the end of reading:

“What do you mean you don’t read books?” And they go, “Well, we just studied Animal Farm in our class, and we read excerpts of Animal Farm and watched some YouTube videos about it.” And I basically lose my mind. I’m like, Animal Farm is a children’s parable. It’s like 90 pages long.

But we still don’t know how bad things really are — for two reasons:

- Literary culture still exists. People read and write things; motivated teenagers might find it easier than ever to find long-form text suited to their taste. But the medium of communication is a stronger filter bubble than any algorithm. I am literally never going to watch a YouTube video or Twitch stream if I can help it; as someone committed to literary culture, I detest them. Because I’m a media scholar I’ve forced myself to overcome this revulsion, to for example write a book about YouTube, but otherwise I would be completely unaware of the gravity of the cultural difference.

- Our political culture is unable to comprehend the depth of the problem posed by changing media technology. The latter point is exemplified by these same liberal progressives Klein and Thompson writing a political manifesto for premised on supply-side innovation and technological progress — which at no point addresses the decline in literary culture which they have both recently podcasted about.

This problem dates back to Plato, as many people who are critical of media technological determinism are quick to point out, and the argument in the Phaedra that this new technology of writing will cause us to lose our capacity for memory. And yet, the critic says, we can still remember things, so maybe writing doesn’t do anything to us at all!

This is put somewhat glibly, but to understand the problem with this argument, we need to appreciate that we don’t have any ground to stand on when it comes to understanding humanity and our relationship to media technology. This is Flusser’s idea of groundlessness, the fact that we are no longer grounded as a civilization because of our changing media technology. We have no stable point from which to evaluate how we experience the world and how other humans in different societies with different mixtures of media technologies appreciate the world.

This means that it’s impossible to make evaluations of whether a change in media technology (or, if you like, progress in media technology) is going to have good or bad effects on us. What we can say is that it will change us. It will change who and what we are. Lacking a stable point to evaluate this from either a positivist descriptive angle or through a normative angle of how humans should be, we don’t have any ability to evaluate whether a given change is good or bad. It is simply a change. It re-writes the rules of good and bad.

The way this plays out in our current social cultural, political environment, is that conservatives raise some opposition to new media technology, because being conservatives, they like at least certain things about our current social, cultural matrix, and they are sensitive to potential changes in this environment. As a result, they raise this opposition to whatever new media technology comes along, and in dialectical opposition, of course, liberals react to this reaction, and come up with reasons why this new media technology isn’t such a big deal. Internet porn is an easy example.

In terms of issue salience, it’s simply not in keeping with contemporary progressive liberalism to think that new media technology is a big deal. Because they are dissatisfied in some ways with the sociocultural status quo, they are able to identify ways in which the new media technology might have positive effects on certain elements that they would like to see changed. They are resistant to the idea that media technology might have broader effects that might reshape our sociocultural matrix in ways that they cannot anticipate or even understand.

And so the key question for liberals is empirical. Do we think that the current type of change is large enough in magnitude that it represents a kind of rotation of our sociocultural matrix? Or do we think that it is the kind of thing that can be managed, that can be adapted, so that we can keep only the things that we like about a new technology, or at a minimum that we can do a utilitarian calculus and move forward as long as the benefits outweigh the explicitly defined harms?

My own position is, of course, that the decline of writing as a media technology absolutely represents a rotation of the matrix, that a utilitarian calculus is ridiculous, and that we cannot hope to get only the good parts without the bad.

I’ve written on this theme many times before; blogging is an exercise in saying the same thing over and over again. So let me try a new metaphor for the same message.

This rationalist tradition tends to reflect its proudest technological achievements back on the human condition. From the 1600s to the present, Western society has likened the body to a clockwork machine (inspired by mechanical clocks and automata), then to a steam engine (reflecting 19th-century ideas of energy, pressure, and fatigue), a brief detour towards the Jacquard Loom and weaving together strands of thought, followed by the nervous system as a telegraph network (mirroring telecommunication systems). Ever since the 1950s or so, the metaphor of the mind as a computer has been central to how we understand ourselves.

But the “computer” metaphor is getting stale. Media theorists have noticed this for a while, and have been busy updating it; I especially recommend K Allado-McDowell’s framework culminating in contemporary neural media.

My contribution comes from having just taught a PhD seminar in Computational Social Science methods, getting into some of the details of how the generative pre-trained transformer models undergirding today’s “AI” work.

There are four essential advances in the past decade that have transformed LLMs into the potentially world-changing technology they are today. The first is simple and well-understood: they have sucked up more and more training data, pirating “the whole internet” and as many books as they can get their hands on; Moore’s Law is probably slowing down but we still more processing power to throw at that data. Big computer better than small computer, so far the old metaphor works.

The second is similar, and can be understood through a parallel to the hard drive and RAM. The training data is the hard drive, a static repository of knowledge; RAM, the active memory applied to a task, is the context window, or how many words the LLM can hold in its memory at once. This is usually a tighter constraint than training data, computationally — just like hard drive capacities have grown faster than RAM, it’s less expensive to grow the size of the training set than to expand the context window.

The third advance is more discontinuous, and directly interacts with the context window: the Transformer (the T in ChatGPT) models that kicked off the new era did so by parallelizing the training process to include all of the words in the same context window at once.

The 2017 paper introducing Transformers was called “Attention is All You Need.” The metaphorical resonance between machines and humans is hard to overstate.

“Attention” here is means the amount of weight the model puts on each word in the context window. An essential advance for today’s extended, chat-based interactions with the models is their ability to “attend to” both the user’s inputs and their own previous outputs.

If you just want to optimize a static classifier or rapid stimulus-response model, you don’t need attention and long context windows; you can just feed it as much data as possible. The larger the context window, the more important attention becomes.

Analogically, we can understand the role of reading in human cognition. Paying attention to an extended narrative requires us to hold a lot in our head; tracing complicated historical accounts requires paying attion to many simultaneous forces.

In contrast, scrolling a feed means shortening our context window. Short-form video like on TikTok, Reels or Shorts makes our attention less important. We are turning ourselves into these simple stimulus-response algorithms—content zombies, as Sam Kriss describes with characteristic cruelty.

It’s now cliche to say that LLMs are replacing our capacity for cognition; cliches often contain some truth, but we can benefit by drilling into the technical mechanism by which this cognition is being outsourced. By abandoning the technology of longform reading and writing, we are shortening our context windows and thus weakening our capacity for attention. At the same time, LLMs advance by expanding their context windows and refining their capacity for attention (in the form of some hideously high-dimensional vector of weights).

Attention is all we need — and the lesson of media ecology is that it doesn’t come easy.

{ 30 comments }

David in Tokyo 07.14.25 at 9:32 am

Just a quick cheap shot.

I don’t know about the English-speaking world (I mostly watch music theory and guitar stuff), but in the Japanese-speaking world, the YouTube videos are pretty good. Lots of videos on current books, literature, music, Go, calligraphy.

Sure, the “shorts” are horrible, as presumably are the various other social media quicky sites, but there’s reasonable intellectual content out there.

A second cheap shot: LLMs are random text generators and have no mechanism for relating the text that they generate randomly to the real world. No “world model”, no inferencing, no logic. No nothing. Just random text generation. It’s neat and surprising how far they get with just that, but it is, in the end, pure BS. Intellectually vacuuous BS.

Gary Markus is good on this, since he understands linguistics, psychology, the history of AI, and what AI really ought to be. Unlike the nearly illiterate college dropouts running the current AI world.

https://garymarcus.substack.com/

I wonder how much has changed since I was kid in the 60s. Sure, I read in those days. A lot. All the time. But mom was a Radcliffe English major (’38) and pointed me in good directions before I took the bit in my teeth. But what percentage of the population read that much in those days? No one I knew, and everyone from my high school went to college. Are the 90% of the folks I see here on the train with their noses in their cell phones the same 90% that wasn’t reading in 1969? But when I check, there’ll pretty much alwatys be one or two folks reading a real book. I’ll occassionally harass a native I catch reading a real book by saying “Nan dai. Kono jidai, mada katsuji yonde iru hito imasu ka?” (OK, I only did it once, and the bloke (an older guy walking down the street with his nose in a book), after doing a double take, said, “Yappari, hon ga suki desu.”)

“Huh? In this day and age are there still people who read real printed books???”

“After giving it some consideration, after all, I like books.”

(Yappari is this insanely common* Japanese word whose sole purpose is to give the speaker an air of careful, thoughtful consideration.)

Oh, yes. The printed newspaper we get has 3 pages of book reviews every Saturday.

*: I (well, my program) count over 29,000 occurences in a small (400,000 page) corpus of Japanese text. Making it one of the most common words in Japanese.

Lee A. Arnold 07.14.25 at 12:13 pm

A solution is to broaden the context window, while using less time to do it.

Have a look at this YouTube video. It is nine and a half minutes long, I’m sorry. But I promise you’ll know more going out than you did going in.

Description: This video has new ideas to win Medicare for All in the U.S. — Part of a graphic cartoon series that rewrites economics to include the basic principles of non-money social organizations. The playlist on the channel page is called “New Addition to Economics (2024-25)”. It wins the debate against market fundamentalism. It has lots of applications.

I just uploaded it. So please tell everybody to go and look at it! Because, well, you know where their attention is heading!

Now the question I have for you is this: How does this video impart meaning?

It animates a visual flowchart language and uses it in a non-mathematical way. 2. It uses a lot of text on the image, text which often moves meaningfully by using cinematographic techniques. 3. And these are combined with an essential audio narration that describes what is going on while you watch it.

This all saves your attention time to do other things, by combining three meaning-purveyances into a more concentrated form. It broadens the context window while using less time.

Lee A. Arnold 07.14.25 at 12:21 pm

By the way, I think the proper metaphor for the mind now is a “snowflake of attention,” into which we place items, to establish the possible linkages between them. (And it’s a rather short list of basic possible linkages, as it turns out.) It accretes and it melts. It is more of a self-maintaining, autopoietic process. See the four minutes of the Knowledge chapter:

Michael Furlan 07.14.25 at 1:02 pm

No plot, just vibes?

Greg Koos 07.14.25 at 1:55 pm

The spoken word whether delivered through audio or video is very linear. It demands specific sets of time. It flows and the person consuming the flow is captured for that set of time.

Text is non-time linear. Yes, while reading you are in a flow of words, but you stop to think about what you have read, you reread a sentence or a paragraph, you engage with and analyze the text.

Critical thinking is central to text. Critical reading was central to the enlightenment. It formed how we re-formed society and government. That is the power of text. It forms our critical abilities.

Democracy is based upon having an electorate with critical abilities. It is easier to fool people by commanding attention by linear media which does not invite critical thought because it does not invite pauses nor review.

When is the last time you used a back button on a video?

Tom Perry 07.14.25 at 2:25 pm

In 33 Years Among Our Wild Indians, Col. Richard Irving Dodge marveled at the cognitive capacities of the pre-literate people he lived and fought among. Plains Indians could communicate by sign language as well as speech; friendly tribes could associate profitably for generations without ever learning one another’s tongues.

A plains warrior, having made a foot journey of several hundred miles, could recall to his mind every landmark and seemingly every bend in the trail. More, he could convey this information to another Indian in a minute or two, using sign language.

These and other abilities, Dodge put down to the fact that the Indians weren’t literate. Learning to read, he was sure, foreclosed the possibility of whites being able to do some of the things Indians could.

oldster 07.14.25 at 3:11 pm

“… dates back to Plato, as many people who are critical of media technological determinism are quick to point out, and the argument in the Phaedra that….”

Plato’s dialogue is usually referred to as “Phaedrus” or “The Phaedrus” after the name of Socrates’ interlocutor.

In typing this comment, the autocorrect function twice changed “Phaedrus” to “Phaedra,” so perhaps that is what happened to you as well.

But we need to try to get the right spelling into the training data so that our LLM’s will learn the right things.

somebody who remembers the youtube adpocalypse 07.14.25 at 6:51 pm

While of course it matters that more people by a factor of 100 watch video game streamers scream anti-trans slurs for six hours a day instead of listening to the radio or watching broadcast television news, I think it’s a bit overdetermined that the current state of these platforms is, somehow, the medium’s message. The medium of these services has to be considered in the context of the deranged tech world that creates and enforces their vision on those working within it. 6-7 years ago youtube would never recommend you a video longer or shorter than, exactly, 600-660 seconds. An analyst at that time would be foolish not to recognize that this is a critical element of youtube’s financial incentives and to establish this purportedly “neutral” decision in the context of advertising, content, etc. But youtube then just, unadvertised, completely changed that, bankrupted and ruined permanently an entire “generation” of 10-11 minute filmmakers, and replaced with with a new one. Now we have a system that permits a creator to post videos of varying lengths but you need to post 1-2 times per day with no breaks, ever. Alternately, you post film-length videos, but you post them more rarely and get your money through an alternate channel like Patreon. Youtube already has taken action against the easy access to Patreon it used to provide (along with many other features which let creators monetize their work in ways that didn’t lead through the youtube advertising ecosystem), and it could do so again any time it wishes.

As for the purported death of the written word, while there certainly is a slump at the moment, and it should not be understated, it should also not be overstated. the number of people who read at least one book all the way through last year may have fallen from 54 percent to 49 percent (that’s NEA stats from 2022-2024), and certainly that’s a trend in the wrong direction. but the most prevalent cohort of people using public libraries are Gen-Z and millenials (ALA 2023), with, among readers in that age group, a firm stated preference for print books even over ebooks. Now, public libraries do a lot of things other than check out books – plenty may be there for coding camp, help with finding a job, tabletop gaming, or for other community events – but in this discussion the critical features of library use lean away from the fear that lowest-common-denominator digital broadcast media will substantially replace personal and physical experience in the long term. Nobody is doing community story time at the library, stopping the story eight minutes in and screaming at the audience to buy taco bell nachos. that, of course, is part of the structural life of youtube and twitch.

rather than concern or despair, I uncharacteristically feel a great deal of hope on this subject. youth today can pick up their phone, talk to their friends, and make a movie in an afternoon. it will stink, and get them nowhere, financially, but the process of learning filmmaking, music-making, dance, and yes, writing, is so much more accessible, mentorship is so much more available, and a supportive community is at their fingertips in a way that it wasn’t even twenty years ago. the only thing that’s needed is some money that isn’t originating in a divorced tech fascist’s desire to control all that is said or thought on earth, and larger than the scale of the same six crumpled dollars passed around from hand to hand like subscribing to a zine in the 1980s. you can take a snapshot and get depressed – maybe that line will indeed go down forever. but i think it might not.

Kenny Easwaran 07.14.25 at 10:53 pm

I’ve been thinking of the neural net as the new metaphor for the mind compared to the symbolic processing computer. It’s easy to think it’s the same thing, since we run neural nets on symbolic computers, but there really are a lot of important differences, that I think we can see with the new level of human-like-ness of the errors that these things produce. (I don’t want to say that they’re the same as humans, any more than clockwork, steam engines, or symbolic computers were, but I think each of these metaphors did in fact advance our understanding of how parts of our minds and body work.)

I do like this metaphor of the context window for an attention head in an LLM though!

Also, I’ll completely endorse David in Tokyo’s first cheap shot – there’s lots of good stuff on YouTube, even though there’s also all the Shorts and stuff.

But I’ll reject his second cheap shot – while LLMs of the BERT/GPT1-3 era were just random text generators that did nothing more than copy high-level statistical patterns in the training data, all of the modern ones have several more aspects built into their training.

Most obviously, they all now have multi-modal training – it’s not just text any more, but they also connect that text to images and videos. It’s not as many modalities as most biological creatures have, but you can’t claim it’s just got text-to-text relationships the way that you could back in 2020, when Bender and Koller wrote their “Climbing Towards NLU” paper.

But I think more importantly, models like ChatGPT o3, Claude 3.7 and 4.0, and Gemini 2.5, all also have “reasoning” training – just as AlphaGo plays against itself and figures out which moves on a Go board help it achieve its goal of winning, these models (after learning to generate plausible random text) try their hand at generating text to lead them to an answer for various mathematical and computational questions where answers can easily be checked for correctness (though they are often hard to find). This training reinforces moves that help it achieve the goal of producing answers that check out rather than answers that turn out incorrect. These “reasoning traces” that they generate are some kind of inference, even if they’re not the logically valid deductive inferences that people like Gary Marcus emphasize as important (perhaps because they were so central to the previous paradigm of symbolic computing). (Also, modern LLM-based chatbots call on good old fashioned symbolic programming in a good number of circumstances where it helps.)

Also, while Marcus likes to claim there are no “world models”, he can only substantiate that if he uses a very strict definition of what a “world model” is. Even as far back as GPT-2, it was clear that there were some sorts of internal states in the LLM that worked like representations of parts of the world, that helped it do better at predicting text than anything simplistically focused on just input-output correspondences would.

navarro 07.15.25 at 3:14 am

@1

these are one man’s observations . . .

i have read in the vicinity of 16,000 books since i began reading fiction and non-fiction books in the adult section of the library when i was 10. in the intervening 54 years i have encountered few people outside my immediate family who read close to what i read.

@op

not to sound snarky but were the occasional creative spellings intentionally placed to see if we were paying “attion”(sic)?

also, while your disdain for youtube shorts is something i can get behind, yet there are people on youtube making literate, even scholarly work. spend some time on dan olson’s channel “folding ideas”. you will be amazed at the scope and power of the video essay in the hands of a master.

regarding llms: this whole sphere of effort smells more like a scam every month that passes.

Michel 07.15.25 at 4:09 am

To be clear, their communication skills.suck. The very best of them osmose them more or less just fine, but that was always true. The rest of them, though…

Tm 07.15.25 at 7:38 am

“it’s simply not in keeping with contemporary progressive liberalism to think that new media technology is a big deal. Because they are dissatisfied in some ways with the sociocultural status quo, they are able to identify ways in which the new media technology might have positive effects on certain elements that they would like to see changed.”

This take seems outdated. The players that are pushing technological change for change’s sake, eager to change the sociocultural status quo – the tech oligarchs – are allied with the reactionary right, whereas progressive liberals are mostly at least somewhat critical of new media.

MisterMr 07.15.25 at 8:21 am

Two random observations:

The neural net as a methaphor for the brain is not new, when “hypertexts” were the new shini thing the idea was that those were a more natural way of thinking than purely linear texts, because the mind is not linear. This logic goes at least back to C.S. Peirce and his logic of infinite semiosis: because each sign is an interpretant of other signs and interpreted by other signs, knowledge becomes a net of signs that interpret each other, potentially infinite. This is true for the mind, and for culture in general (wikipedia as a methaphor of culture).

My hate of Marshall McLuhan: I once read McLuhan’s book where he said that “the medium is the message”, where he says that there are “hot” media, like book, that require concentration, and “cold” media, like comics or TV, that are supposed to be fast and not require concentration, and this is what “the medium is the message” means, that TV will stupidize everyone because it is a cold medium that doesn’t require concentration and thinking.

Problem is, comics, that he describes as a cold stupidizing medium (probably thinking of silver age superhero comics that honestly weren’t that smart) are not really a different medium of books, they are still ink on paper: the same medium used differently.

A similar argument could be made of tabloids that have clickbait titles and short articles about love affairs of VIPs: they are cold stupidizing media in McLuhan’s logic, but they are still the same medium, technologically, of books and comics.

So if we speak of pure technological determinism McLuhan’s theory fails big time.

If we use the term “medium” in a more nuanced way, so that we include also chains of distribution and expected public, then we can see tabloids, comics and books as three different mediums, but then the idea that different publics, reached by different social systems (distribution), want to read different messages isn’t all that surprising honestly.

Also as a counterpoint to the idea that attention spans are going down, while I think it is true, but compare a TV serie from the 70s like Columbus or Star Treck to a modern netflix serie: the older ones were way more stupidized because they had to compress a plot in 30 minutes, plus people had to be able to follow the plot even from the middle of an epiosode or while dining and chatting with family or both; today instead we have more complex bingeable series.

So the pendulum swings in different directions for different media.

Though it is true that, books being an extremely compressed form of narrative, they were more useful in the past and we will be moving somewhat away from that specific ultracompressed model.

Also I googled for an historical statistic of book sales, but I found nothing, so I’m not even sure people are reading less now that they were in the 70s.

David in Tokyo 07.15.25 at 8:23 am

“but you can’t claim it’s just got text-to-text relationships the way that you could back in 2020, ”

Sure you can. Ask any of the image generators to show a clock/watch showing any time other than 10:10, and it’ll fail. Ditto for “a wine glass filled to overflowing with wine.”

(That’s cheap writing. Once you’ve discovered some stupidity in the neural models, the twats put in a kludge to fix the problem, so they may have figured out kludges to handle those particular cases. The point is, of course, that the underlying technology gets those things wrong, because it doesn’t actually do any reasoning.)

Like navarro says: “this whole sphere of effort smells more like a scam every month that passes.”

I audited Minsky and Pappert’s grad seminar my freshperson year. That year (fall 1972), Minsky’s thing was going over, in gory detail, why the “perceptron” model was a crock. Hilariously, the history of “neural AI” after that was to gussy up the models so they don’t do the stupid things the simple models did, and then pull out the gussy parts and go back to stuff that doesn’t work for the next generation. Nowadays, they’ve simply given up on that cycle and blithely do things that don’t work, and put kludges in the front ends to get around obvious problems.

To misquote Jerry Fodor “The brain doesn’t work that way”: it’s a great title and applies exactly to the current “neural” models. There’s absolutely nothing in them that looks even vaguely like what’s going on in mammalian neurons. It takes a friggin enormous “neural net” to even partially simulate a single neuron, and they’re still not getting to the connectivity issue (a cubic millimter of gray mater has about 70,000 neurons and multiple of KILOMETERS of axon. (And axons can do computations locally independent of the cell body.) This whole round of “neural” stuff is even a worse crock than the perceptron stuff was over 50 years ago.

(In their defense, it’s a way to tame and get mileage out of the SIMD computers that are so common (GPUs) and getting better. Thus the Go programs are ridiculously good.)

ozajh 07.15.25 at 9:17 am

just like hard drive capacities have grown faster than RAM

Is that actually true, in percentage terms?

Anders Widebrant 07.15.25 at 11:56 am

I’ll keep the cheap shots flowing – while I don’t know as much as I probably should about LLMs, I think that it’s not quite right to say that the context window is as RAM to the trained model’s hard drive.

The trained model is a static object that does not update as it’s being used. That makes it more similar to an application or a computer. Crucially, it also makes it radically dissimilar to a brain, which even when fed hundreds of short videos can – if it wants – find patterns and insights and meanings across them all.

Vasilis 07.15.25 at 12:52 pm

“The trained model is a static object that does not update as it’s being used. That makes it more similar to an application or a computer. Crucially, it also makes it radically dissimilar to a brain, which even when fed hundreds of short videos can – if it wants – find patterns and insights and meanings across them all.”

The brain is not “updated” either when it finds patterns across short videos. Not sure what you’re trying to say.

As for the comment that LLMs look/work nothing like human brains, why should they? Anthromorphize much?

JCM 07.15.25 at 3:45 pm

But Kriss’s point is that the claim that our attention is narrowing is only something we’re likely to say if we come at the matter from the traditional canons of what kind of thing we attend to, isn’t it? That if we think about things from the point of view of the “zombies” we get a different object of attention, viz., the algorithm itself—something that only becomes visible through extended attention?

Lee A. Arnold 07.15.25 at 4:00 pm

People who are wary of McLuhan’s theories will enjoy the deft intellectual demolition in the slim volume titled, Marshall McLuhan by Jonathan Miller, in the Modern Masters series edited by Frank Kermode (Fontana Books, and also Viking Press, 1971). Among his other considerable talents Miller was a brilliant intellect and science writer, and a lucid and entertaining prose stylist.

Mitchell Porter 07.15.25 at 8:17 pm

David in Tokyo #14

“Ask any of the image generators to show a clock/watch showing any time other than 10:10, and it’ll fail.”

That’s a good trick but it can be solved with sophisticated verbal pre-processing. The reason AI image generators trip up on this, is that they have only learned language to a certain degree of sophistication. The bulk of their knowledge concerns how to map simple descriptions onto visual features. It is hard to learn the semantic nuances needed to understand “any time other than 10:10” (or “a room without an elephant”), from a list of concrete pairings of images and descriptions.

On the other hand, large language models can learn such subtleties. So the request intended for the image generator, should instead first be sent to an LLM, along with the request that it be re-written e.g. at the level of “explain like I’m five years old”. The LLM can then e.g. tell the image generator to draw a watch showing the time 11:37, and the result will satisfy the original request.

JPL 07.15.25 at 10:32 pm

@The OP:

In the second sentence of the first paragraph, why did you use the attempted nominalization “emerge” instead of the already available, and perfectly acceptable nominalized form “emergence”? (Since you say you are concerned with finding “the right words”, how did the thought you were trying to express differ from what would have been expressed by the available form “emergence”?) I found that use puzzling and I’m curious. Either way, I would judge the claim expressed between the colon and the semicolon in that sentence to be false, or at least, as they say, overstated.

BTW, I see on the tv screen that The Atlantic reports that the Trump admin is going to incinerate 500 tons of emergency food that otherwise would have been distributed to people in great need. If they wanted to end the program, they could have phased it out gradually, to give people a chance to find alternatives. As it is, it’s like you’re face-to-face with a mother and a small child in desperate need of food, and you are capable of looking that child in the face with full attention and saying, “I have plenty of food here, but I’m just not going to give you.” You can’t save everybody, but you can save those who you are in a position to save, and you ought to do so. Anybody, e.g., in the villages misunderstood by Evans-Pritchard would would have known intuitively that they must help. So what exactly has gone wrong with European culture?

David in Tokyo 07.16.25 at 1:27 am

Anders is, of course, correct here.

“The brain is not “updated” either when it finds patterns across short videos. Not sure what you’re trying to say.”

Of course the brain is “updated”. We remember (some aspects of) everything we attend to. Normal people don’t “persevere” (in the psychiatric technical sense). Your aging aunt who repeats the same question over and over again over dinner conversations didn’t do that until recently.

Keeping a rough memory of just about everything we do is a central part of what makes us human and what makes human intelligence so kewl. (In particular, it sneakily avoids the need for solving certain computationally intractable problems.)

(Sometimes we have to work at it. For example, I neglected to take my morning meds, and had to think back to how I got from the breakfast table to the couch (where I read the newspaper and Science), and Oops, there wasn’t a fetch a glass of water step in there. Yikes.)

Somewhat seriously, the problem with our current AI overlords is that they don’t respect human intelligence, and think their stupid tricks with just a bit more data will really be “intelligent”. They’re arrogant and wrong.

nicopap 07.16.25 at 7:28 am

The idea that the brain metaphor is influenced by transformer research doesn’t pass the sniff test.

Like: the metaphor of memory layers with different access speed in the brain exists since at least 2 decades (George Miller’s memory span). For computers: I have a C programming book from the 1980 that graphs the difference in speed between CPU cache, RAM, and disk.

The most recent metaphor for the brain I heard was as a complex system, the modular cognition framework. It reminds me a lot of how software projects organically grow. For the metaphor, I’ll have a shot: it is a workshop, a bunch of tinny intellectual tools you use for various aspect of the intellectual work, and that you use to build other tools that may be useful in the future or the immediate task.

For the impact of media, I found Tommaso Venturini interesting: Oral traditions share a lot of characteristics with today’s social media: repetition (as in meme format), re-use of narrative templates (the hero’s path) and a few others. Why? Because those are technologies that help people remember facts without writing them down. The bard’s story, like a social media post, is ephemeral, you can’t refer to it in a future date.

Outside of that, yeah. Information is not useful by itself, it needs context and analysis, a way of integrating with your own knowledge. But I don’t think the medium is the culprit here, it’s the lack of dead time, it’s difficult to just sit down and either talk with someone or think in a structured fashion.

Jim Buck 07.17.25 at 9:01 am

David in Tokyo @1:

(Yappari is this insanely common* Japanese word whose sole purpose is to give the speaker an air of careful, thoughtful consideration.)

To me, that looks how speakers of Yorkshire dialect used the word Happen e.g.

“Happen, after all, I like books.”

engels 07.17.25 at 11:55 am

The title of this post sounds like a Gen Z anthem, replacing the boomers’ All You Need Is Love.

Mtn Marty 07.17.25 at 2:56 pm

I wonder what the new media has done to our subconscious and unconscious minds. Being a person that likes to “sleep on it” i’m decision making, I wonder about the connections between how the media comes in and how it is processed by our longer run mind. Do people dream differently? Do the ideas that “pop into our head” days, weeks or months later operate the same way?

Theodora 07.17.25 at 5:56 pm

I’m approaching the point where pretty much anything thinkpiece-adjacent about the panoply of techno-cultural crises we are facing right now feels like going through the motions. (Maybe this is too Woke Cancel Culture of me but perhaps I’m just “triggered” by being forced to remember Sam Kriss, who was credibly accused of sexual assault, being given a wide platform for his misanthropic extremely-online-millennial-posting-misanthropically-about-others-who-are-extremely-online slop.) It’s like Sedgwick in the reparative reading essay: we still have so much faith in exposure. But the problem is obvious: the profit motive, the attention economy, the speed-up writ large, Silicon Valley oligarchs, useless Democrats…I don’t know. I’ve started so many books in recent years about how phones are bad only to put them down because, like, I know phones are bad already.

Obviously thinking what we are doing is useful, so I’m not entirely pessimistic; I did enjoy reading this post, as I think the context window framing is lucid. (I do find your take on YouTube faintly absurd given the sheer quantity of quality stuff buried under the slop-pile, but stubbornness can be an underrated intellectual virtue, so I get it.)

Some of my response is also just my own depressive and anxious temparament — exacerbated, of course, by the precise conditions these diagnoses diagnose, including a material and psychological precarity that frankly undercuts my capacity for sustained impersonal or dialectical thought. A symptom of being under attack is feeling under attack, and without the cathartic outlet of researching and publishing on this stuff it seems to function in my life as a means of making me feel rotten. I suppose all I am saying is that little makes me feel my powerlessness more intensely than this genre of cultural critique, even as my general incoherence and learned helplessness are symptoms of the disease we are justly and rightly attempting to diagnose.

This is hardly about the post at this point, though, so you know.

Fortus 07.19.25 at 6:23 pm

Is “matrix” a literary concept? I find it funny that an essay arguing for the supremacy of the written word posses the central question in terms we all understand instantly thanks to a film.

Jim Buck 07.20.25 at 6:57 am

“Matrices vary from fully automatized skills to those with a high degree of plasticity; but even the latter are controlled by rules of the game which function below the level of awareness. These silent codes can be regarded as condensations of learning into habit. Habits are the indispensable core of stability and ordered behaviour; they also have a tendency to become mechanized and to reduce man to the status of a conditioned automaton. The creative act, by connecting previously unrelated dimensions of experience, enables him to attain to a higher level of mental evolution. It is an act of liberation-the defeat of habit by originality.”

? Arthur Koestler, The Act of Creation

J-D 07.20.25 at 8:42 am

Wiktionary offers twenty definitions of the word, the third of which is:

This usage is illustrated by a 1920 quotation.

Wiktionary’s eleventh definition is:

Comments on this entry are closed.