I am at the airport in Melbourne (again). I’m sitting in the window eating one of those excellent boxes of kale, broccoli, beans, seeds, peas and a boiled egg that I am grateful are now available at airports. Next to me a father and daughter are observing the world – look at how that plane looks like a giant shark! And oooh, here come the bags!

What looked like an automated process when a Virgin Airlines robot told me my bag on the conveyer belt was heading towards the same destination as me turns out, my eyes now tell me as this adorable pair observe the world out the window, is also a matter of human labour. A human is driving all the bags to the plane.

One characteristic of the combination of neoliberal managerialism and technological automation is that a whole lot of things are experienced as less material. Even the airport cafe in which I sit. I selected my salad and approached. Ugh, one of those giant iPod-looking terminals. I look it up and down. It did the same. Thankfully a silent human, hovering weirdly in the background, took two lanky steps forward to help me scan my salad and press the right buttons to enable me to pay for it.

This human-machine tag team surely a transitional arrangement, for it makes no sense this way. In due course, surely, I will confidently approach the giant terminal and the young man will have a job doing something less weird. And there will be literally no one to complain to, or ask for help. This, of course, is the ideal experience under neoliberalism, enabling endless cost-saving enshittification (I bet it starts with the seeds in the salad) with no evidence of consumer dissatisfaction (because there is no one to collect said complaints).

This I also know because, like nearly everyone I saw at this week’s mega-meta-humanities and social science conferences in Melbourne, my plane from Sydney to the best-caffeinated city in the world, was cancelled. Needing to fix something in the rescheduling, all I could do was listen to Virgin’s recorded message about how cancelling your flight when you are almost at the airport two hours from your home is perfectly normal and fine, actually.

When it comes to money – which (as we know from the authority of songs about money) makes the world go around – such disembodiment seems kinda fitting.

Since the ATM, money comes from machines. And now, as cash becomes ever-more scarce, it dwells in machines – abstract ledgers that we can check using other machines, and which monitor how much money (but not cash) that we have. Kinda like the silent human who stepped up to press buttons on the confusing terminal, it hovers ever-more in the background, seeming ever-less tangible.

And yet, like that human – and the one driving my bag to the plane just about now, the circulation of money combines all sorts of automation with human labour.

This, plus how bankers pretty much run the world (and have since approximately 1844-ish), makes me want to understand something about the relationship between banking labour (including machine labour) and historical capitalism.

I think this deserves more than a little substack, but in the first instance let me tell you a little bit about a paper I gave a few days ago at the law and history conference in Melbourne. The archival foundation of this paper – meaning the primary historical records I used (in a preliminary way) to talk about banking labour – were some early records of the United Bank Officers’ Association, which was (and so is its successor) a union, formed in 1919.

The United Bank Officers’ Association grew like mad, reaching 10% density for the industry within a few months. Banking was bigger metaphorically than it was numerically, and yet soon found 50-60 new members for its union in Sydney every day in 1919.

Bankers? In a union? Wot?

Yeah, that is what the banks wanted people to wonder too. So in an act of capitalist solidarity, several of Australia’s biggest banks (such as they were in 1919) got together to hire a hot-shot lawyer who would point out, repeatedly, that banks are lovely warm cuddly organisations creating a supportive, highly professional and (importantly) exceedingly well-dressed environment in which white-collar elites were given every opportunity for advancement and riches – given their wonderful proximity to capital – in a way that is supportive of their family and financial obligations.

Certainly, the banks’ lawyers argued, this was not what Australia’s special and (almost) unique arbitration system intended when it referred to ‘workers’, who were dirty and wore terrible clothes (according to the lawyers, not me, obv).

As it turned out, bankers were recruited at approximately age 15 and paid really, really badly. This meant that families who recognised the ‘prospects’ of banking work would subsidise their children’s clothing budget (and sometimes other things) to ensure that this foot in the door would pay off for families that found themselves at the arse end of empire, needing to build a new middle class trajectory for their family.

Wider recruitment was needed during the Great War in banking (as in other industries), so that women and less-elite young men became more important. Union activity grew and bankers like others, including clerks and journalists (with whom the bankers consulted when deciding to unionise), began to see the strength embodies in their work.

And yet, because of the importance of their ‘prospects’ in relation to the sacrifices demanded for entering the industry, bank workers were subject to arbitrary managerial decision-making that kept them fearful and subservient. In 1919 they’d had enough, and collectively pressed for something better.

This is cool – and there is more to this story that I will get to another day. But I want to know about the value of the work they were doing. And here Australia’s arbitration court records offer something exceedingly fabulous. The court’s purpose (once they told the banks and their lawyers that this whole business about their workers not being eligible to form a union was rubbish) was to establish levels of responsibility and therefore salary rates. This means they brought in so many bank employees and asked them to describe exactly what they did at work. Records like these, from Australia’s arbitration system, are not used nearly enough in my view. It is pretty exciting to use a beautiful collection like this one.

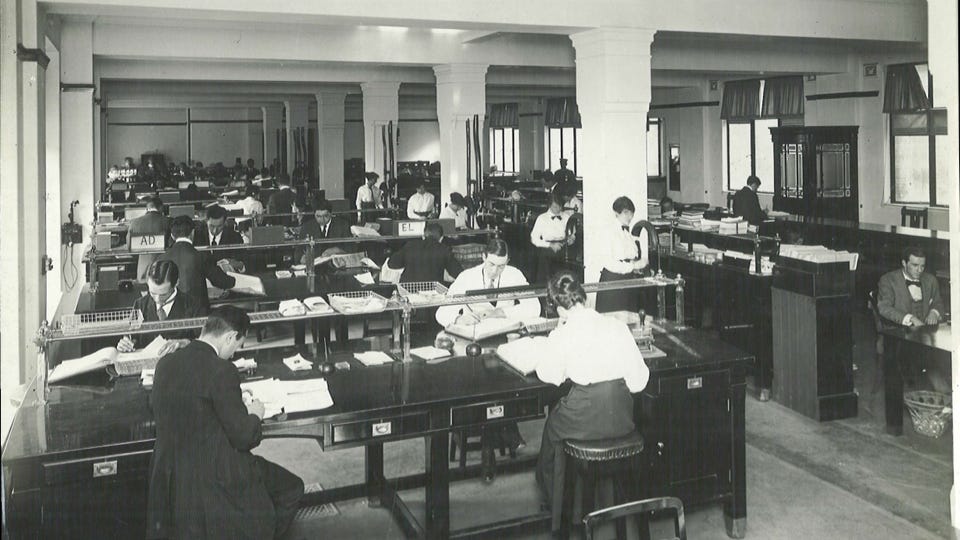

As well as an archive that describes 1919 banking work in glorious detail, we also have a beautiful collection of glass plate negatives at the Reserve Bank of Australia archives showing bankers c.1916-1923 doing their work. I am able to (or, perhaps more accurately, able to attempt to) match the descriptions of banking work in the arbitration court to these pictures.

Look at this picture below, for example. We can see some sense of the gendered division of labour in that it is only women working the pneumatic tubes on the right, facilitating communication, probably between the tellers we can’t see and the ledger keepers who dominate the picture. Most of the ledger keepers are men, but some are women. This had become especially common during the war, the arbitration testimony tells us, but in some banks it was not that uncommon beforehand.

Image: General Banking Floor, Commonwealth Bank Head Office 1916, RBA Archive

From teller to ledger

Then the teller takes the duplicate deposit slip to the cash book department. This is like mail-sorting and the deposit slips are organized so that the correct ledger keeper collects it.

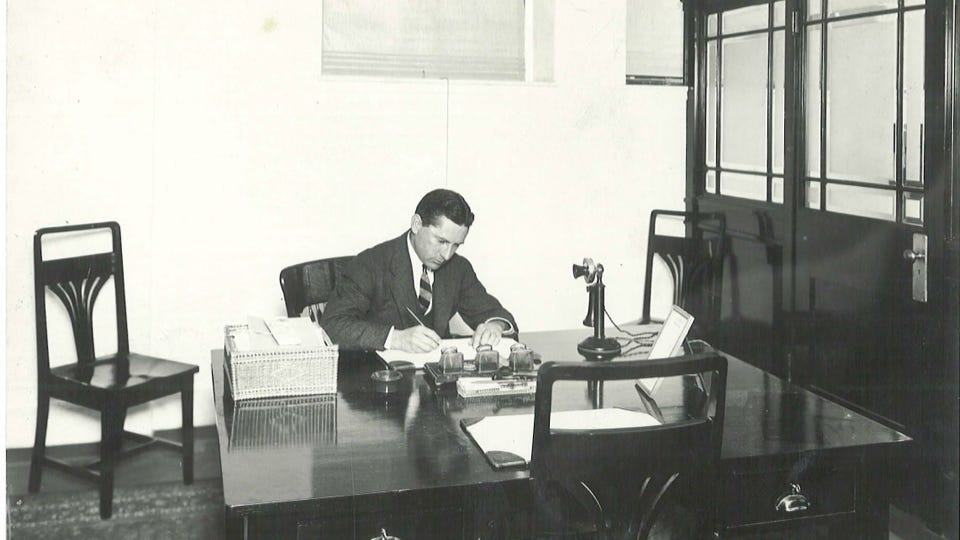

Image: Commonwealth Bank – Head Office cnr Pitt Street & Martin Place – Banking Chamber (view 4) – c.1917 (plate 733), RBA Archives. You’ll note the pre-Nazi swastikas in the floor tiles, at that time denoting prosperity. I popped my head in to the building the other day and they don’t seem to be there anymore, surely correctly.

Ledger-keepers performed the work currently done by the banks’ big computer systems.

The ledger keeper would take the deposit slip and enter it against the correct account. At this point it is important that the ledger keeper crosses the deposit slip with a pen so they don’t accidentally enter it twice. They keep the deposit slip on hand until they have enough to call over a clerk, usually a woman (Montgomery Shepherd calls them ‘lady clerks) who checks that each deposit has been correctly entered in the ledger. This happened about twice a day.

As well as the ledger, the ledger keeper has a loose cash sheet where they jot down all their deposits and cheques, for withdrawals. This was then ‘machined’.

Image: Interior new War Loan offices, April-May, 1920: First floor office (plate 200) – zoomed in on machinist.

This picture is actually from the war bonds department but I’ve zoomed in on the woman doing the machining.

She is using an adding machine, a Burroughs I think. At the end of each day the ‘lady clerk’ adds up the deposits for each ledger keeper. These are pasted into the ledger.

Montgomery Shepherd told the arbitration court that ledger keepers were expected to look out for death notices of the people their ledger covered.

Another ledger keeper, William Elmhurst Parnell Carboyd, explained that each ledger keeper is responsible for 500-600 accounts.

He was recalled to give the court more details in which he explained that his ledger consisted of: 483 credit accounts and 91 overdraft accounts. In recent times he also dealt with 74 Stop payment notices and 192 ‘authorities’, which gave the authority for various firms to operate on account. He was also responsible for special notices, which include letters of credit and transfer of balances to the London office.

26 year old John Chandos Elliott described telephoning and telegraphing fund transfers using code that is kept in a secure code book.

The arbitration court was obviously trying to establish levels of responsibility in order to set wages, so they were especially interested in what happens when there was a mistake.

The machining is intended to act as a check on human adding, but is actually a source of errors. Apparently it is easy to forget to ‘reset’ the machine so that there are already numbers stored.

John Elliott said that when there is an error they try to re-trace it. But when it is work that has been machined they can’t easily tell if it is ‘the girl or the machine’.

This reminds us that the work of banking is as entangled with its technologies as it is with the ideas about virtue and integrity that were embodied in the work processes, so that while the machine might enhance a woman’s capacity, the machine was also as plausible an agent of error as she was.

Almost all of the banking jobs that were described in the arbitration court are now done by machines, which also need to be regulated in ways that ensure the integrity of the banks. I think there is space here to think about the feminisation of machines, governed of course by a deeply masculine IT profession, and the connection of feminising and digitisalising labour to masculinised aspects of banking work.

But for now, let’s focus on the ledger keepers where we can see that the physical and technological labour (that is, work being done by both the girl and the machine) of keeping the ledger is fundamental to the functioning of the bank. This is simultaneously embodied and disembodied; one one hand, the ledgers are abstractions of exchanges using currency at the tellers and elsewhere in the economy. But on the other hand, the ledger also seems to be the thing that is most real to the bank, so that the work of the ledger keepers produces and maintains the currency that matters, at least to the bank. That is, when the ledger keepers work, this produces the only thing that really matters to the bank, the ledger.

Since bitcoin, ledger theories are a bit trendy. And (or but?) they might be onto something.

I’m going to give this a bit more thought. If you have ideas about this I’d love to hear them. For now I reckon the ledger (and the ledger-keeper, whether human or machine) might give us some clues about the ecosystem (thinking as an actor-network-system type), the technologies of power (thinking Foucauldianly), or the institutional (thinking through institutional lenses, or else the ‘rule of law’) or maybe (so say some business folk) even the location where the energy of capital and labour collide. Maybe.

Why do I think this might matter? Well we have these two archetypes, in fiction as in real life, of the banker. The first, from Mary Poppins’ Fidelity Fiduciary Bank (left picture below), where a kind of upright masculinity not only holds together British finance but also England herself – and her colonies (listen to the song OMG). So ‘upright’, right? And on the right, the Wolf of Wall Street, where wild speculation is paired with toxic masculinity.

As a historian of professional virtue, this is intriguing. And, I suspect a ledger theory of banking might enable me to see these (upright v toxic masculinities) as two sides of the same ledger, so to speak. That is, the integrity of the ledger is what enables wild speculation.

This will also mean that instead of thinking of money as ‘circulating’ in some sort of disembodied manner, we can better see the labour (human and machine) that makes it go – just like watching the human drive the bags to the plane.

This is a short version (plus airport stories) of a talk I gave as part of a plenary panel and the Australia and New Zealand Law and History Conference on Currency recently. Many thanks to the organisers for having me.

{ 10 comments }

John Q 12.10.25 at 6:50 am

This is the only scene from Mary Poppins that I can still remember in any detail from my first and only viewing at the time of its cinematic release. I was struck by the miracle of compound interest, even then.

engels 12.10.25 at 8:51 am

This human-machine tag team surely a transitional arrangement, for it makes no sense this way. In due course, surely, I will confidently approach the giant terminal and the young man will have a job doing something less weird. And there will be literally no one to complain to, or ask for help

Other possibilities:

1 he’ll be on the dole, or refused the dole

2 he’ll be overseeing your scanning from a distance and shouting at you to do it faster/better as if work at the salad store

(2 is what British supermarkets sent to have progressed to.)

D. S. Battistoli 12.11.25 at 3:34 pm

What a vivid case study of a sort of capitalist flow: at first, all tasks and roles are assigned to men of the socially dominant group. Then, especially during labor crises of all sorts, women and racial and ethnic minorities are brought in to do marginal work (such as clerkship), eventually getting greater responsibilities. And eventually technology, developed by teams mainly consisting in men of the socially dominant group, is acquired to perform the marginal work, eating in ever more to core activities (that of ledger-keepers).

I’m sorry, that’s a very pedestrian reading. But your post opens so many interesting paths!

engels 12.15.25 at 8:22 pm

Btw may I mention, at the end of a trip to Spain, that Alsa (main bus company) replaced its staff with touchscreens and it’s a shitshow even by Spanish standards: horrible interface that doesn’t accept minor spelling errors and constantly tries to upsell you crap, huge queues for the single machine in a bus station with 20 platforms, machines won’t take card/cash or are completely broken and there’s no notice or way to report it and an endless Sisyphean churn of people trying and failing to buy tickets (for journeys that might have been really important to them…)

Trader Joe 12.16.25 at 4:35 pm

A very interesting look at the very old days of banking.

I’d note (and this all US perspective) that as recently as the 1980s a much greater than you’d expect portion of transactions were still primarily paper based with actual required ink signatures on them and a verification process which matched physical slips of paper against what was on the system. It was really only in the 1990s where larger banks completely did away with most of the paper and late 90s when smaller local or single state banks did the same.

I can recall multiple instances where we had to chase down customers for what we called “actual signatures” as we were provided documents that were faxed, copied or otherwise conveyed. If there wasn’t ink produced by a human hand on the page, it wasn’t deemed a valid or complete document by bank auditors.

Id also add that the concept of ‘ledgering’ remains firmly embedded among Wall Street traders. In real time a trader can see his “pad” which tells where his long positions, short postitions, float and leverage stand and all of that needs to be balanced against a mathematically determined value at risk based on the volatility of the underlying positions. For a trader – the system is god and is deemed right until proven wrong (contra the example of balancing the girl vs. the machine).

When a single trader at Barrings (Nick someone) brought down that bank in the mid-1990s it was because he was operating in Singapore (if I remember correctly) where systems were still pencil and paper first and a verification versus the system second. Part of his scam was basically using that lag to take outsize positions and then close them before the system caught up and could see how large of bets he was taking. Not really possible today, at least until someone figures out how.

Thanks for an informative piece.

Tm 12.17.25 at 9:46 am

“One characteristic of the combination of neoliberal managerialism and technological automation is that a whole lot of things are experienced as less material.”

“This human-machine tag team surely a transitional arrangement, for it makes no sense this way. ”

“This, of course, is the ideal experience under neoliberalism, enabling endless cost-saving enshittification”

“an endless Sisyphean churn of people trying and failing to buy tickets”

Surely, if enshittification prevents customers from buying the product or even making payments, that cannot be a viable business model? It can’t, can it??

This issue of automation and enshittification is full of contradictions. Remember that LLM chatbots not only don’t even remotely generate a profit, they rely on whole armies of (low-paid) human enablers sifting through data for them. And the whole online commerce is made possible by armies of humans sorting and delivering packages. Sure a lot of it has been automated but the delivery end hasn’t so far. I find it hard to believe that for example ordering food online requires less human labor, all told, than going to a restaurant in person. It is true that the experience is radically different but the appearance of “dematerialization” is totally an illusion.

This brings to mind the absurd performance of a human dancer wearing a robot costume demonstrating the prowess of Elon Musk’s genius new robot army. It was the most ridiculous and embarassing business presentation ever but it was enough for the investor class. Yesterday it was reported in some pseudo investor news that Teslas “robotaxis” will soon be able to run without human monitoring. There is no evidence whatsoever that this will happen any time soon (remember that Waymos have to be monitored in real time round the clock, and remeber also that the market leader is burning billions and has no plausible path to profitability any time soon) but who cares?

Tesla stock reached an all time high yesterday with an insane price earnings ratio of 333 that everybody knows is wildly inflated. A whole chunk of the economy and trillions in investments now depend on the belief that automation and “AI” will in the near future make a huge fraction of the global labor force redundant. A belief that is probably illusory and also highly contradictory – how will they generate profits if nobody has a job any more – but it has been enough to make a bunch of already insanely rich oligarchs insanely richer and they’ll do whatever it takes to keep the grift going for as long as possible and to offload the damage on small investors and the public, knowing full well that the bubble will inevitably burst.

And in the meantime they’ll continue destroying decency (because a decent society wouldn’t tolerate their behavior), science and education (because an educated society wouldn’t admire them as geniuses), democracy (because feudal level inequality cannot coexist wirth democracy), the rule of law (because their wealth depends on big time fraud), and burn the planet to fuel their insane machine.

Tm 12.17.25 at 10:08 am

Trader 5: “It was really only in the 1990s where larger banks completely did away with most of the paper and late 90s when smaller local or single state banks did the same.”

Why then did I have to literally make every single payment with a paper check even less than 15 years ago (and also have to cash checks regularly)? In Europe, payments were made by online banking from the 1990s (before the internet, payments were made with paper slips that you gave the bank teller).

My US banks did have online banking in the 2000s, but you couldn’t use it to make payments online. You still wrote a paper check and mailed it to the recipient (or brought it in person). The backwardsness of the US banking system is unfathomable, and I’m sure the main reason why paypal was so successful.

Tm 12.17.25 at 10:27 am

“money – which (as we know from the authority of songs about money) makes the world go around”

Since you mention it, might as well remember that ‘Money makes the world go around’ is from the 1972 film version of Kander and Ebb’s ‘Cabaret’, a musical essentially about the rise of the Nazis.

Trader Joe 12.18.25 at 11:38 am

@7 TM

You are correct, the ability to pay electronically varied widely, but generally had more to do with the recipient of the funds than the bank’s ability to process.

To this day I can still only pay my water bill via physical check (I can use an auto-charge to my credit card for a fee).

Equally, as you note, if you received a check for whatever reason you had to physically take that to deposit it and that persisted well into the 2000s. Both of these were sort of the point of my comment which was that for all of the technological advances, there is still considerable room available for further automation – enshitified or not.

Tm 12.21.25 at 1:01 pm

Trader Joe agreed, but why is the US banking system so backward? I never used it received a paper check in Europe in all my life.

Comments on this entry are closed.