Just north of the Alps, on the border between Germany and Switzerland, lies beautiful Lake Constance. And on the northwest shore of the lake is the lovely small city of Constance, Germany.

Constance is well worth a visit. A lot of German cities have rather bland or unattractive centers, thanks to the American and British air forces. But Constance escaped these attentions entirely, because the Allies didn’t want to risk any bombs landing in neutral Switzerland. So Constance has an unusually intact Old Town with lots of interesting old buildings, some going right back to medieval times.

Constance also has this::quality(80)/images.vogel.de/vogelonline/bdb/1272600/1272674/original.jpg)

A nine meter tall, 18 ton statue of a medieval sex worker. She’s down at the harbor, on the lake. She rotates once every four minutes. Her name is Imperia.

You may reasonably ask, what? And part of the answer is, she’s memorializing the Council of Constance, the great political-religious council that happened here 600-some years ago, from 1414 to 1417. And you may ask again, what?

I’ll try to explain.

Constance

Lake Constance gets its modern name from the city of Constance. And the city of Constance is named after Constantius, a fourth century Roman emperor.

[probably this guy, though it might have been his grandson. it was the 4th century, stuff got confused.]

Back in the first century AD, the Romans pushed up through the Alps into what’s now southern Germany. They brought peace to the region via their traditional mix of mass murder, ethnic cleansing, and forced Romanization. They seem to have built a bridge at Constance — the lake tapers down to a narrow neck there. And credit where it’s due: the Romans loved nothing better than building transport infrastructure. Bridge going north, good Roman roads going south, inevitably a town sprang up. Later, in the 4th century when the Empire was turtling up against the ever more aggressive barbarians, the trading town built walls. It became a border fortress, and got a new Imperial name.

(You have to work a bit to find corners of Europe that haven’t been touched by someone’s empire. Roman, Frankish, Byzantine, Holy Roman, Ottoman, Spanish, French, Russian, British, German… ruins and roads, castles and place names, borders and battlefields. The continent is pock-marked with them like acne scars.)

The Romans eventually departed, but the bridge and the town seem to have survived. Certainly both were still there a thousand years later, when the Catholic Church convened a General Council there in 1414.

So is Imperia about the Roman Empire, then?

No, not at all. Well… not directly.

Three Popes, One Council

“And if a man consider the original of this great ecclesiastical dominion, he will easily perceive that the papacy is no other than the ghost of the deceased Roman Empire, sitting crowned upon the grave thereof: for so did the papacy start up on a sudden out of the ruins of that heathen power.” — Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan

For a while, back in the 14th century, there were two rival Popes. Each had his own Papal court and hierarchy, each was doing all sorts of Papal things — collecting religious dues, appointing Bishops and Cardinals, excommunicating heretics — and each was recognized by about half of Europe. This was generally agreed to be a bad situation! So there were several attempts to fix this problem. They all failed, and one went so spectacularly wrong that it produced a third Pope, recognized by another couple of European countries.

At this point pretty much everyone agreed that something drastic had to be done. So a General Council of the Church was called, with implicit power to sit in judgment on all three rival Popes. Italy was problematic for a bunch of reasons, France was in the middle of the Hundred Years War —

[Branagh or Olivier? discuss.]

— so after some discussion it was decided to convene the Council in the small neutral city of Constance, which if nothing else was centrally located.

In Conference Decided

“A conference is a gathering of people who singly can do nothing but together can decide that nothing can be done.” — Fred Allen

The Council of Constance is just so darn interesting.

I’ll try not to chase too many rabbits, but here’s a thought. In the early 15th century Europe was, in terms of global civilization, a backwater. The Chinese were more technologically advanced, India was richer. Asia was full of cities that were larger, cleaner, safer, and better designed than Europe’s grubby little burgs. Heck, the contemporary Aztecs had a capital at Tenochtitlan that was bigger and nicer than anything in Europe, and those guys were barely out of the Stone Age.

Europe had nothing that the rest of the world particularly wanted to buy, which meant that Europe had been running a trade deficit for literally centuries. (This would lead to a serious economic crisis later in the century, as the continent nearly ran out of gold and silver.) Militarily, Europeans had been losing battles and wars to non-Europeans for a while, and this would continue for some time. In particular, the Ottomans had just embarked on a long career of kicking Europe’s ass. Within a century, a huge chunk of the continent would be Ottoman provinces or tributaries.

And yet. Somewhere along the line, Europe went from “D-tier also-ran kind of lame civilization” to “planetary apex predator”.

Why? Why Europe?

Some of the world’s smartest people have spent lifetimes of scholarship trying to answer that question. Not for a moment will I imagine I can add anything useful to that great debate. But here’s an offhand thought: there’s a short list of things that are, historically, unique or nearly unique to Europe. One of those things? International conferences.

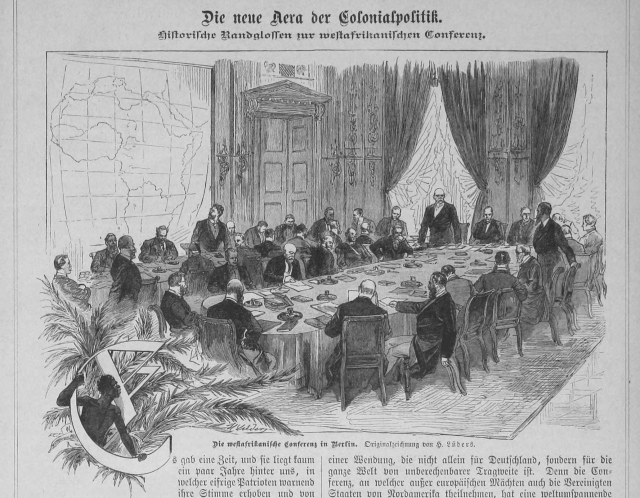

[it doesn’t get much more European than this.]

This is probably because international conferences started as a particularly Christian thing. The early Church was spread broadly but thinly across a politically united Roman Empire that had, for a premodern state, unusually excellent transport links. (See earlier comment re: Romans and transport infrastructure.) So it made sense to periodically come together: to keep doctrine and practice consistent, to resolve leadership disputes, and just generally to settle questions that couldn’t be worked out locally. The great-grandfather of them all was the Council of Nicaea, back in 325 AD, which gave us the Nicene Creed.

[BEGOTTEN NOT MADE HERETIC iykyk]

And there were lots more Councils, all through late Antiquity and the Middle Ages: Chalcedon, Constantinople, Lateran, Lyons.

But there’s a second line of mostly secular conferences called by Europeans to resolve international disputes: most typically to end a war, but often with a sidebar of “and let’s try to set up some sort of international order”. And you can argue with a straight face that the Council of Constance is the takeoff point for this second line.

Because Constance was a Church council, yes. But it was also political in a way that previous medieval Councils hadn’t been. It was attended by kings and dukes and counts, lawyers and professors and representatives of Imperial Free Cities — in fact, the lay attendees may have outnumbered the clerics. It relied on the Emperor Sigismund to provide security and enforcement. Its decisions required buy-in from the secular authorities. Voting at the council was done by “nations” — groups of Churchmen, but sorted geographically by region within Europe. And while Church reform and heresy were on the agenda, the overriding imperative was straight-up power politics: to resolve the Papal schism and settle the Church’s internal government.

So on one hand, Constance was just another in that long line of Church councils from Nicaea to Vatican II (1962-65). But at the same time, it was arguably the first great multilateral peace conference. Lodi, Westphalia, Vienna, Versailles, Yalta: Europeans have been holding these conferences for a long time. There’s a direct line from Constance to the G-20.

— No, I’m not claiming that international conferences are what made Europe special. I’m just noting that these secular peace-and-international-order councils really get going in the 15th century, right around the time that Europe begins its slow ascent out of mediocrity. Almost certainly a coincidence! Still: interesting.

Deliverables

So the Council of Constance had three declared goals, plus one goal that was undeclared but universally recognized.

The declared goals were:

1) Fix the whole three Popes thing.

2) Deal with heresy. Specifically, deal with Jan Hus, who was the beta version of Martin Luther, and his followers. The Hussites had basically taken over one European country already, and were threatening to spread.

3) Reform the Church, which everyone agreed was spectacularly corrupt, and doing a pretty terrible job of providing spiritual guidance and moral leadership to Catholic Europe. (This was cross-wired with (2) because the Hussites were claiming to be, not heretics, but reformers.)

The undeclared goal was

4) By asserting the superiority of a Church Council over Popes, convert the Catholic Church from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy.

Nobody was publicly saying this was the plan, but this was totally the plan. There had been a bunch of bad Popes already. It was clear that giving that much power to anyone was a dubious idea to begin with, and that this was made worse by a selection process that favored ruthless conniving corrupt SOBs.

Getting rid of the Papacy was unthinkable, of course. But regular Church Councils to keep the Popes in check? That seemed entirely doable.

Key Performance Indicators

They succeeded at (1) and failed at the other three.

They did burn poor Jan Hus. It’s a sad story and I won’t go into the details. TLDR, they burned him, but the Hussites took over Bohemia anyway — the modern Czech Republic, more or less — and stayed in power there for over a century. The secular rulers around them did manage to contain the Hussite heresy and keep it from spreading, but that wasn’t because of anything the Council did.

But the really consequential failures were that they utterly failed to reform the Church and they didn’t curb the powers of the Papacy. The Church would remain horrifically corrupt, and the Popes would remain autocratic — and all too often greedy, cruel, and completely uninterested in providing spiritual or moral leadership.

It would take nearly another century for these particular chickens to come home. But the eventual, inevitable result was the Protestant Reformation.

[hammer time]

By failing to fix the system, the attendees of the Council guaranteed that the system would eventually explode.

But, really, how could they do otherwise? Cardinals and bishops and abbots, counts and dukes and kings, priests and professors… they were all products of the system, and they were all benefiting from it.

Somewhere, Imperia is smiling. We’ll get back to Imperia.

One fled, one dead, one sleeping in a golden bed

So what happened to those three Popes, anyway?

Well: John, the Neapolitan Pope, was a pretty sketchy character even by the low standards of late medieval Popes. Among other things — many, many other things — he was plausibly suspected of having poisoned his predecessor. So the Council offered him a deal: resign, and we won’t open an investigation into these accusations. Since an investigation would lead to a trial, and a trial would lead to a conviction, Pope John agreed and stepped down.

But then! John slipped out of Constance — disguised as a postman, some say. He fled to the castle of a friendly noble, un-resigned, and declared the Council dissolved.

The Council wasn’t having it. The Holy Roman (German) Emperor summoned an army to besiege the castle. John fled again, but the Emperor’s forces followed. Eventually he was caught and dragged back to Constance, where they did put him on trial, and convicted him too. He spent several years in comfortable but secure confinement. He was allowed out once it was clear that he would behave himself, i.e. not try to be Pope any more.

Now, one of John’s few accomplishments as Pope was choosing the Medici of Florence as his bankers. Did you ever wonder why the Medici were such a big deal? It’s because they were the bankers for the Papacy for almost a century. Immense sums of money flowed into Rome from all over Europe. All of it passed through Medici hands at some point, and of course the bankers took their cut.

And, credit to the Medici, they used at least some of that money to become some of the greatest patrons of art that the world has ever known. Michelangelo, Botticelli, the Duomo, Donatello, the Sistine Chapel… all that happened because of bad Pope John.

[“Award of a Sole Source Contract for Financial Services”, fresco, c. 1509]

When the disgraced ex-Pope eventually died, the reigning Pope didn’t want to give him a burial in Rome. So the grateful Medici whisked John’s body off to Florence, where they gave him a nine-day funeral. Then they built him a nice little tomb. It was eight meters tall, marble and gilt, with Corinthian columns and a bronze effigy — you know, the usual — designed by Medici client artists Donatello and Michelozzo. It’s still there in Florence today.

[phrases rarely found together: “Medici” and “tasteful understatement”]

Gregory, the Venetian Pope? He cut a deal. He agreed to resign if (1) the Council subsequently acknowledged that he had been the One True Pope all along, so that his rivals were declared schismatic antipopes, and also (2) he got a unique one-time title of “Second Most Important And Holy Guy In The Church, After The Pope”. The Council decided this was cheap at the price, and agreed.

So Gregory is still counted by the Catholic Church as an official Pope. (Which means he was the last official Pope to resign the office until Benedict XVI’s abdication in 2013, five hundred and ninety-seven years later.)

[he even got to keep the hat]

Benedict, the Spanish Pope? He refused to resign. But the Council went to work on the remaining countries and monarchs who were supporting him, and talked them around. So Benedict ended up abandoned by most of his supporters. He died a few years later, mule-stubborn to the end, isolated and mostly ignored.

That time they elected the Pope in a shopping mall

Once the Council had eliminated or sidelined the three Popes, they needed to choose a new one. For this, they used a unique, one-time-only system of voting. Council attendees gathered into geographic “Nations”, each nation picked six guys to represent them, those six guys cast one vote. This was an attempt to put a new, Council-based system of Pope selection in place, since the existing College of Cardinals process kept throwing up Popes who were scheming evil bastards.

It didn’t take. The next Papal election took place when there was no Council, so they went right back to the College of Cardinals.

[and they’ve kept it ever since]

But they also had the problem of where to hold the election. Because traditionally, Papal electors are isolated, cut off from outside influences until they decide. So they needed a building that was large, but that could be sealed off, but also handed over to the electors for some indefinite period of time. As it turned out, medieval Constance had exactly one building that fit the requirements: the town Kaufhaus.

Today the word “Kaufhaus” gets translated as “department store”. But the Constance Kaufhaus was a combination warehouse and retail center. Foreign merchants kept and sold premium goods there. It was a big building full of little shops selling luxury items. Literally, a high-end shopping mall.

Still, needs must. And credit to the electors: they managed to reach a consensus and elect a Pope who was, if not brilliant, at least not an incompetent, a criminal, or a monster. Pope Martin V would rule for 13 years and while he wouldn’t do much that was memorable, neither would he poison his enemies, appoint a bunch of nephews and bastard sons to high office, run the Church into bankruptcy, or otherwise disgrace the office.

Of course, this goes to a deep structural problem. The Council chose a kindly mediocrity because they were afraid that a strong Pope would claw power back from Councils. (Which is exactly what happened, a Pope or two later.) But the Church desperately needed reform, which a kindly mediocrity couldn’t possibly deliver.

Also, the College of Cardinals absolutely hated the idea of anyone else being involved in electing the Pope. Partly this was a status issue. Partly it was about ambition — most Popes came out of the College, after all. (Still true.) But most of all, it was about cold hard cash. Would-be Popes were often willing to pay immense bribes in order to buy votes. Kings and Dukes would throw in more bribes to support or oppose a particular candidate. Banks and wealthy families would coolly lend money to finance these bribes, since backing a winning Pope could mean an instant flow of massive wealth.

This is, of course, how the Medici became the Papal bankers. It was they who funded the election of bad Pope John in the first place.

[Allegory of a Papal Election, c. 1480. the winged figures represent the Medici, scattering flowers (money) as they blow the candidate to the shores of success. the handmaiden (the Church) is about to clothe her in a robe decorated with flowers (even more money). the candidate gazes into the middle distance, seemingly unaware.]

So reforming the electoral process would not only have been a hit to the Cardinals’ status, it would also have drastically curtailed their future income. It’s no surprise that they weren’t enthusiastic about the new system, and abandoned it as soon as they could.

Somewhere, Imperia is still smiling. We’ll get back to Imperia.

Everybody goes home

The Council wrapped up in 1418. Joan of Arc would have been in first grade, if medieval French peasant girls went to first grade, which they didn’t. She was about 10 years away from starting her brief incredible career as the savior of France. Johannes Gutenberg was a freshman at the University of Erfurt. He was about twenty years away from inventing the printing press. Over in England, a handsome young Welshman named Owen Tudor was hanging around the court of King Henry V. In a few years, King Henry would die of dysentery. His widowed Queen would marry handsome Owen. Their grandson would be the first Tudor king of England, and their descendants are sitting on the British throne today.

Jan van Eyck was in his twenties, just getting started on his career as a painter.

[weird mirrors were already a thing]

And down in Portugal — a kingdom small and obscure even by medieval European standards, out on the far edge of the continent — Prince Henry the Navigator was forming an ambitious plan. Portugal, like the rest of Europe, was running out of gold. But there was gold down in Africa… somewhere. It came north regularly, after all, in caravans across the Sahara. The trade was controlled by Islamic middlemen, who took a hefty cut.

But what if Portuguese ships could work their way down along the African coast? They might find the source of the gold… and who knows what else?

[just getting started]

And that’s the story of the Council of Constance.

But wait, you ask. What about Imperia?

Yes, well… this post got a little out of hand. But Imperia is not forgotten! Modern Constance has a nine meter, 18 ton concrete statue of a medieval sex worker that rotates every four minutes, and there’s a reason for that. We’ll get to her story shortly.

Because she is most certainly still smiling.

[Edit: Part 2 is up, and can be found here.]

{ 46 comments… read them below or add one }

AndrewMcK 02.21.26 at 1:22 am

You tease

PatinIowa 02.21.26 at 1:35 am

Please tell me you’ll manage to fit the Black Death into all of this.

marcel proust 02.21.26 at 2:15 am

1) A pedantic correction: From the map (see centrally located), on the northwest shore of the lake is the lovely small city of Constance, Germany appears to be incorrect. Rather, Constance appears to be on the southern shore of the lake.

2) But here’s an offhand thought: there’s a short list of things that are, historically, unique or nearly unique to Europe. One of those things? International conferences… No, I’m not claiming that international conferences are what made Europe special.

Europe was much more fractured than any of the other contemporaneous major old world civilizations. China was pretty much united, as was most of the Indian subcontinent until the end of the 14th C. Much of the rest of Asia was dominated by various descendants of Genghis Khan, and what conferences they had were usually family affairs.

BTW, whatever the reason for this fracturing (geography?), some economists credit it for Europe’s going from “D-tier also-ran kind of lame civilization” to “planetary apex predator” . It gave many people opportunities that would otherwise not have existed, fleeing from one polity to another after offending a local ruler or losing out to a rival for some contract etc: freer thought, etc.

3) Branagh or Olivier? Definitely Branagh (I’ll admit up front that the only one of Olivier’s Shakespeare movies I like is his Richard III, which PBS broadcast in the mid 1970s, when the American version of this character was going through his own fall from power. Watching the play, it was impossible not to see uncanny parallels).

Olivier displayed his typical idolatry for Da Bard; perhaps not surprising in this case since it was clearly shot as British propaganda late during WW2 (according to Wikipedia, “Winston Churchill instructed Olivier to fashion the film as morale-boosting propaganda for British troops fighting World War II.[5] The making and release of the film coincided with the Allied invasion of Normandy and push into France.”). The pomp and pageantry is quite tedious. Branagh toned this down a great deal to good effect. Even better is the Hollow Crown version; much as I like Branagh’s approach to Shakespeare (esp. the comedies that he’s filmed), I prefer Hiddleston as Henry V. It doesn’t hurt that viewing the plays in the Hollow Crown in order places the play in context better than Branagh’s version; moreover, coming to Henry V after the 2 Henry IV plays (with Hiddleston playing Hal in both) allows us to see the title character grow into his kingship.

oldster 02.21.26 at 5:10 am

Great stuff, Doug!

“ Voting at the council was done by “nations” — groups of Churchmen, but sorted geographically by region within Europe.”

I wonder whether this organizing structure was borrowed from the medieval universities?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nation_(university)

Doug K 02.21.26 at 5:52 am

thank you, awaiting the further adventures of Imperia with great interest..

These popery shenanigans were entirely a Catholic show, due to the papal infallibility doctrine that was part of the Great Schism. The patriarch Leo went rogue, decided he was the One True Pope, and generated a lot of history.

Orthodox Christians have been getting along with multiple patriarchs for millennia now, each elected by a wild variety of mechanisms (link from my name) but mostly councils of the clergy and laity, which seems to work a bit better.

Peter T 02.21.26 at 6:10 am

By the early 15th century Europe was on a broad par economically and technically with China and India, remembering that those hosted great empires with much greater aggregate wealth than any single European state (and hence larger capital cities and a larger luxury market). India did textiles, China porcelain and silk and agriculture, Europe did metals and ships. It was probably pulling ahead of the older Middle East (the ottomans were rapidly becoming as much a European as Middle eastern power).

The failure of Europe to follow the usual trajectory of rebuilding empire after Rome and the Carolingians (who after all ruled from the Ebro to the Elbe and the middle Danube) is peculiar. Basically, if you were a recognised kingdom in Europe by 1100 you were still there in 1900 (the extinction of Poland in the later C18 caused such unease it was resurrected within 30 years in the usual form of personal union). I put it down to the unusual basis of political legitimacy that was consolidated in the post-Carolingian turmoil: states were the collective expression of ‘peoples’ whose king was their representative to God. So you could collect crowns (see Charles V, who had at least seven), but not re-order the collectivity. So Croatia comes under the Hungarian crown in the 10th century but remains a distinct legal entity all the way to 1918 and beyond. Ditto Bohemia, Aragon, Ireland, Poland, Norway ..

It certainly enhanced military competition and state depth.

MisterMr 02.21.26 at 7:59 am

Interesting post, but I have two nitpicks:

When I was in high school, the theory was that the middle ages were a dark period until the year 1000, at which point the tide turned and european economy started growing again. My understanding is that today archaeology shows that the turning point was actually around the year 800 (but also the slide downwards was backdated to the year 300). So if we speak of levels, it is true that Europe was behind or at best on par with China or India in 1400, but if we speak of direction Europe was already 600 years into the upswing.

Other nitpick: Gutenberg didn’t invent the printing press, he invented movable characters that made his version of the printing press way more efficient than the one that was already in use (where I think the artisan had to carve each page anew on wood).

Peter T 02.21.26 at 10:05 am

oldster – more likely that the universities borrowed from Church councils – which were held quite frequently at various levels (provincial, regional, royal). After all, theology was the standard university major and graduates keen participants.

MisterMr – China and India had major upswings ahead: population and – as far as we can judge, wealth – rose sharply under the Ming and early Qing. India still had the Mughals to come, and Iran the Safavids. The laggard is the old Middle East – Iraq, Syria and Egypt, which took a long time to recover from the Mongols and, for Egypt, the Black Death.

Doug Muir 02.21.26 at 11:00 am

PatinIowa @2, the worst of the Black Death was over by 1415. The big epidemic in 1347-49 was followed by another bad one in 1361, then three more smaller-but-still-bad outbreaks over the next 50 years. By 1415 Europe’s population was probably about half of what it had been 70 years earlier.

This had complicated effects. The simplistic narrative is “while it was horrible, it did raise wages and per capita income while significantly reducing pressure on land and resources. Rising wages, in particular, encouraged investment in labor-saving devices and capital.”

And that’s not wrong, but it’s very incomplete. So for instance: there was a huge amount of pushback on rising wages, so that in many places they rose only a bit or not at all. Or: the Black Death hit Europe much harder than it hit China, Central Asia, or India. But it may have hit some parts of the Middle East harder still. If losing half the population was a long-term net positive, why did it lead to investment and innovation in Central Europe but not in Egypt or the Levant? Or: if there was less pressure on resources, why was 14th century Europe still running short on bullion, and why were most Europeans still living with food insecurity even when there was twice as much land per capita?

Anyway, super interesting, but probably a topic I’ll leave to a real historian. (You know I’m not a historian, yes? Interested amateur at best.)

Doug M.

Doug Muir 02.21.26 at 12:00 pm

Marcel @3, counter-pedantry: the old city is indeed on the south bank. However, because it was surrounded on three sides by Switzerland, for a long time it could only grow north. So today the majority of Constance’s area, and most of its population, are on the north bank.

I’m mildly skeptical that Europe’s political division played a direct, straightforward role. “fleeing from one polity to another after offending a local ruler or losing out to a rival for some contract etc: freer thought,” — I’ve seen this argument and it’s always struck me as a Just So Story. Yes, Stadluft ist Frei Luft and all that. But how exactly did this translate into innovation, increased spread of useful ideas, relevant investment? Not “isn’t it obvious” — what specific examples?

There are a few, but less than you might think, and a lot of them are post-medieval — i.e., the knitting frame, which was rejected in England but was able to find investment and modest success in France, came in the 17th century. Meanwhile, there are a number of counter-examples. For instance, a major innovation in metal technology with important military implications took place in Nuremberg… and then didn’t spread for decades, because the Nurembergers kept it a trade secret. If they’d been part of a larger kingdom, the Crown would have had every reason to break up their monopoly. But since they weren’t, it was a couple of generations before rivals finally reverse-engineered the wire-pulling technology that let Nuremberg make cheap high-quality chain mail.

TLDR, the “borders let people and ideas go where they worked best!” isn’t completely ridiculous but overall it’s IMO thin gruel.

I do think there’s an argument to be made that political division led to intrastate military competition led to the development of the fiscal-military state plus a bunch of military innovations that made European armies very hard to beat. But that came later — 17th century, not 15th.

If you go back to the 1400s, you see a bunch of actors, state and nonstate, with very limited capacity. The states are mostly weak and painfully underfunded. Nonstate actors, you see some real concentrations of capital — Medici, Fuggers, Grimaldi, Mendes — but their investment is disproportionately going into land, agriculture, construction, or conspicuous consumption. (I love me some Botticelli, but it’s hard to argue that the Allegory of Fortitude led to Europe dominating the world.)

Here and there you do have some interesting stuff like the Fuggers investing in metallurgy and silver mines, including pushing for innovative techniques that alleviated the bullion shortage. But those were very much exceptions. Broadly speaking, there’s not a lot of investment going into the stuff that is going to make Europe deadly.

People like to witter on about the Ming treasure fleets. But the more interesting comparandum is the Ming repair and expansion of the Grand Canal. This was happening at almost exactly the same time as Constance — early 1400s — and the Ming state mobilized over 100,000 workers continuously for most of a decade.

It was totally worth it, of course. The Canal was literally China’s economic and strategic backbone for the next couple of centuries. But the point here is that no 15th century European entity, state or otherwise, could mobilize anything remotely like this level of investment.

The expansionist ball gets rolling with the Portuguese drive into Africa. That was very much a public-private partnership, because neither state nor private actors had the capital to make it work, at least at first. It did eventually prove very profitable — the Portuguese reached what is now Senegal in the 1440s, and gold, ivory, spices and slaves started flowing up immediately. (Yes, the Atlantic slave trade predated Columbus by decades. If Portugal had a 1619 Project, it would be a 1444 Project.)

So there was enough revenue to provide capital for further investment, in everything from bigger and better ships to longer voyages. So long-term there was a virtuous circle / snowball effect. But because the initial investment was so dinky, it took literally most of a century before the payoffs started to become economically and strategically important.

oldster @4 and Peter T @8, IIUC they were absolutely borrowing it from the university system. The Council was attended by hundreds of university professors — of course, most professors were also clerics, at least formally — and lots of other scholars, amateur and professional, clerical and lay. You could argue with a straight face that it was an academic conference every bit as much as a religious or political one.

(Not even kidding. One side effect of the Council that I didn’t mention, because the post was already very long: a huge trade in manuscripts, swapping and recopying. IMS it’s how a number of rare manuscripts survived, including most famously Lucretius’ De Rerum Naturae. More generally, it helped spray Italian humanism all over the continent.)

Doug K @5, I wasn’t aware that Papal infallibility played an important part in the Papal Schism? If I’m wrong I welcome correction.

Doug M.

PatinIowa 02.21.26 at 9:02 pm

Also not a historian, as I’ve been gently reminded by some of my history colleagues. I suppose historian-adjacent as I did my diss on Thomas More and executions. There was a little, “Isn’t this intellectual history?” from the English faculty, and I had to negotiate that.

I’m always happy to think along with other amateurs.

Anyway, you’re right: fascinatingly complicated. I’m recently retired, so down the rabbit hole I go.

For example, I’ve seen it claimed that the behaviour (i.e. corruption, self-dealing, and flight from the infected) of the church during the plague and a general sense of apocalypse contributed to the Reformation, giving the Hussites purchase on the fears of … well … everybody.

Doug M.: If memory serves, papal supremacy mattered more than infallibility. Infallibility didn’t become dogma until Vatican I in 1870. Of course, in arguing for it, the council claimed, “We’re simply articulating what everybody has always known,” as one does. Another rabbit hole.

Which is why I come here.

Austin Loomis 02.21.26 at 10:16 pm

Did you know they made an action figure? Link in name.

Alex SL 02.22.26 at 12:48 am

I am not a historian, but it seems obvious to me that what changed the fortunes of Europe was the combination of ocean-going ships and the discovery of large landmasses whose inhabitants were relatively easily subdued because they had no immunity against pox, flu, and other assorted diseases that the inhabitants of Eurasia had contended with for millenia. This allowed European nations to build large economic areas that multiplied their power to the degree that they could then take on India and China at moments when those empires showed internal weakness, as every nation inevitably does sooner or later. Even then, some of them squandered the opportunity, like Spain, which mostly achieved genocide and extraction of silver but failed to build the kind of trade economy and proto-industrial division of labour that Britain did.

The strongest argument I have seen for the proposition that institutional arrangements matter is the lost opportunity of China’s naval explorations led by Zheng He. The commonly told story goes that the bureaucrats shut the project down because they didn’t like foreign influence being brought in with such trade, and that that couldn’t have happened if China had been as politically fragmented between competing nation-states as Europe was.

Doug Muir 02.22.26 at 8:09 am

Austin Loomis @12, oh my goodness. My understanding of the human condition continues to evolve.

Peter T @6, “Europe did metals and ships” — not in the early 1400s we didn’t. European metallurgy was nothing special. European ships sucked, full stop. We had to borrow pretty much everything from the Arabs (lateen sails) or from the Chinese via the Arabs (rudders, compasses). About the only thing Europeans brought to the table was clinker-building.

Okay, but just because a technology is borrowed doesn’t mean you can’t put it to good use, right? Right! Except, European ships still sucked. They were small, slow, clumsy, and not very seaworthy.

The Chinese had ships that were much bigger and safer. The Arabs had ships that were faster and could sail closer to the wind. In the early 1400s Europeans were just cautiously getting started on the sorts of long-distance blue-water journeys that other Old World civilizations had been doing for centuries.

Certainly after 1400 European ship technology got steadily better and better — for a bunch of reasons, of which the Portuguese voyages of discovery were one of several. By the early 1500s, with the deployment of the galleon, Europeans had pulled ahead of the other Old World civilizations. The big Iberian galleons could, as the saying goes, outrun anything they couldn’t fight, and outfight anything they couldn’t run from, and they were literally capable of sailing around the world. Galleons absolutely allowed the Portuguese to fight well above their weight in the Indian Ocean. Heck, galleons were originally /designed/ for that purpose. And the fact that Portuguese shipwrights could develop that design and build it, and on pretty short notice, tells us that by the early 1500s European naval technology had come a long, long way.

But that was 100 years after the period under discussion. In the early 1400s? We sucked.

Doug M.

Doug Muir 02.22.26 at 9:27 am

…some additional nerdery about galleons, because I am that guy.

1) The galleon was one of those fundamentally sound military designs, like the Ak-47 or the Jeep. So it stuck around for a very long time. There were tweaks and upgrades, but in the 1660s the Spanish conquered the Marianas Islands with galleons that would have been instantly recognizable to their great-great-great-grandfathers in the 1520s.

2) The galleon grew out of the carrack. The carrack is a mid 1400s design, and it’s what Columbus and Vasco da Gama used. The carrack was much better than anything Europeans had in the early 1400s — in particular, it could do long-distance blue water voyages. Very roughly speaking, the widespread deployment of carracks in the late 1400s meant that European naval technology had roughly caught up with the other Old World civilizations, while the galleon meant we had pulled ahead.

3) That said, while the galleon was an excellent design, it didn’t mean that Europeans always and automatically won. In the Indian Ocean, yes, Portuguese galleons could catch lighter Arab and Indian ships and literally blow them to pieces. In that theater, there were multiple instances of small groups of a few galleons defeating much larger enemy fleets.

But when the Portuguese reached the South China Sea, they were confronted with Ming Chinese war junks. These junks were even bigger than galleons, and they carried cannon too. The galleon still had an edge — better guns, more maneuverable — but it was no longer absolute technological dominance.

Furthermore, at that point the Portuguese were operating at the end of a 10,000 kilometer long supply line, while the Chinese were in home waters. The Chinese had more war junks, and they could replace losses almost instantly, while the Portuguese were months from their forward base at Goa and literally years away from home.

This goes a long way to explain why the Portuguese, so bold and murderously aggressive in the Indian Ocean, suddenly became much more chill and reasonable when they reached Chinese waters. The Ming navy was green-water, not blue-water: ships with short legs, designed for coastal patrols, pirate suppression, and customs work. They didn’t do long-range force projection. But in Chinese coastal waters, they were very formidable. The Portuguese seem to have recognized this instantly, and adjusted their behavior accordingly.

Doug M.

Doug Muir 02.22.26 at 9:36 am

Alex SL @13, your first paragraph yes, second paragraph hard no.

IIUC there’s now general agreement that the discovery and exploitation of the New World was necessary to later European dominance of the Old World. New World resources were absolutely important: gold and silver bullion, fish, leather, sugar, timber, all these things were a major windfall for Europe.

But “necessary” is not “sufficient”. Without the New World Europe would surely have stayed a relative backwater, but the New World alone wasn’t enough to put Europe on top. Spain and Portugal had pretty much a free hand in the Americas for almost 150 years, and it didn’t lead to global dominance. Quite the opposite: by 1650 Spain was in decline, while Portugal had temporarily ceased to exist.

The French, Dutch and above all the English were able to leverage their New World possessions more effectively… but they barely /had/ any New World possessions until after 1600, and for decades after that their colonies were basically rounding errors.

“The lost opportunity of Zheng He” — no no no. This is a myth. It’s wrong on pretty much every level. Stopping here because I don’t want to spend the next half hour writing a very long comment explaining why.

Doug M.

Peter T 02.22.26 at 10:18 am

Doug

In the friendliest way, have to disagree. By 1400 German and Italian smiths were churning out reasonable plate armour in quantity, cannon were in common use, mining was a skilled occupation. Europe was on a par with China or India and ahead of the Middle East. While I think gdp figures do not carry much weight in these very different economies, most estimates put core western Europe of 1400 at level with or ahead of China (obviously the comparison is inept – China is larger than western Europe, and Flanders was very different to, say, Scandinavia).

On ships – by 1400 or a little earlier European shipbuilders had combined northern hull forms with southern building techniques -: frame first, carvel planked (Arab merchant ships followed the older tradition of hull first, frames inserted), multiple masts with a mixed rig. They could take rougher seas and longer voyages: year round trips from Flanders to Italy were routine. Unger notes that by 1400 Genoese cogs of 600 tons – forerunners of the carrack – were hauling from the eastern Mediterranean to the English Channel. Arabic writers noted that Italian ships were larger, and stronger than their own. Rigging was a mix of lateen and square (lateens are efficient up-wind but need large crews and are hard to reduce sail quickly). So no, European ships of 1400 did not suck.

LFC 02.22.26 at 4:14 pm

Alex SL @13

Wallerstein argued that Europe’s political fragmentation (which included both stronger and weaker polities) contributed, and even was essential, to the emergence of an integrated (though he doesn’t use that word) Europe-wide economy during what W., following Braudel, called the “long 16th century”, i.e., roughly 1450 to 1640. See The Modern World-System, vol.1.

Mike on the Internet 02.22.26 at 6:11 pm

For an interesting survey of European metallurgy and mining through this period, it’s worth checking out De Re Metallica, published in 1556 and translated into English by Herbert Hoover (a world-leading mining expert before he became president). It’s public domain and easily found online. (Yes 1556 is a long way from 1414, but the book traces the development of mining and metallury from Roman times up to its present).

J-D 02.23.26 at 2:23 am

If it were possible to compare literacy rates in different parts of the world in the fifteenth century, what do you think the results might be?

If it were possible to compare rates of book publication/production/circulation, what do you think the results might be?

Phil 02.23.26 at 10:45 am

His widowed Queen would marry handsome Owen. Their grandson would be the first Tudor king of England, and their descendants are sitting on the British throne today.

Considering that women were excluded from the succession until very recently, it’s odd to look back and realise that the current Head of State’s accession derives from him being the son of the great-great-granddaughter of the 5-greats-granddaughter of the great-granddaughter of the granddaughter of that widowed Queen. (I think.) Excluding women from the succession altogether – Handmaid’s Tale primogeniture – would be an interesting What If; I wonder if we would just have ended up being ruled by (say) Mortimers or Howards, or if the cocky thoroughbreeders* would have completely run out of male second and third cousins some time in the last half-millennium.

*Jake Thackray

Tm 02.23.26 at 11:58 am

„But Constance escaped these attentions entirely, because the Allies didn’t want to risk any bombs landing in neutral Switzerland“

There were in fact a few instances when the allies accidentally bombed Swiss border towns. The old town of Constance is in fact unusual in that it sits on the South shore of the Rhine, which forms the border. It’s probably the only German territory South of the Rhine border (there are however several Swiss exclaves North of the Rhine). According to Wikipedia, the city (which had achieved independence of the Bishop and became reformed in the 16th century) would have liked to join the Swiss Confederation but the rural member states wouldn’t allow it, fearing that the city states become too dominant.

BTW The historic German name of Lake Constance has nothing to do with Constance.

Doug M. 02.23.26 at 6:16 pm

Peter T @17, you make some good points, and yes — “sucked” was too strong. But I was reacting to “Europe did metals and ships”, which c. 1400 was certainly not the case.

Metals — cranking out lots of armor doesn’t mean your metallurgy is actually good. In Europe around 1400, it just meant (1) there was constant endemic warfare creating a market, plus (2) the Italians successfully marketed plate armor as a luxury / status good, and then the Germans figured out how to produce lots of it cheaply.

Cannon definitely weren’t “everywhere” in 1400. Battlefield cannon wouldn’t be significant for another 40-50 years. I think the first European battle decided by cannon was Chatillon, in1453? Thinking about battles around 1400 — Nicopolis, Homildon Hill, Tannenberg, Ceuta, Agincourt — I can’t think of one where cannon played a significant role.

Cannon on ships were just starting to be a thing. The first naval battle I’m aware of where cannon were important, if not decisive, was the Venetian destruction of an Ottoman fleet at [googles] Gallipoli, 1416. And afaik the first decisive use of siege cannon to successfully open a breach, at least in western Europe, was… good old Harfleur, 1415.

But anyway! Take a step back: “Europe did metals and ships”. Well… if Europe “did metals”, was early 15h century Europe exporting metal goods to anyone? As far as I know, no we weren’t. Toledo swords were already a thing, but afaict they weren’t exported outside of Europe. And Europe was desperate for export goods. So if there had been a market, some eager Genoese or Venetian would have found it.

Ships — yes, “sucked” was too strong. But we definitely weren’t ahead of the rest of the Old World, either. We can see this by the simplest possible metric: around 1400, and for decades afterwards, European ships regularly lost naval conflicts to non-European rivals.

I mentioned Gallipoli, where the Venetians beat the Ottomans. They won that battle because of superior leadership and seamanship. But the Ottomans came back to kick Venice’s ass repeatedly, and more generally to score victory after victory in the Mediterranean.

Constantinople fell, then the Morea, then Trebizond. The Venetians lost Crete and their Aegean and Greek holdings. The Ottomans rolled up the coast of Albania. The Genoese lost Crimea. The Ottomans then captured Otranto, on the Italian mainland, in 1480. The only reason that didn’t ramp up into a full-scale invasion was Sultan Mehmet’s sudden death. Nevertheless, if you’re looking at the 15th century Mediterranean, there’s a consistent pattern of growing Ottoman naval dominance. The only serious setback came when the main Ottoman fleet was destroyed in 1488… by a storm, while fighting their Islamic rivals, the Mamluks.

To be fair, the Mediterranean and the Atlantic were two different worlds. There was overlap, but the very different circumstances of the Mediterranean led to different shipbuilding, naval designs, and tactics. Most obviously, galleys made a lot more sense in the Mediterranean, where storms were more predictably seasonal, summers were usually calm, and where you were almost never more than a hard day’s row away from food and fresh water.

The interesting sort-of exception here is Genoa, which — as you note — diversified into more “Atlantic” designs like the cog, and later the carrack, because they were trading in the Atlantic as well. But this didn’t translate into naval success. Cogs didn’t stop the Ottomans from throwing the Genoese out of Crimea and the Black Sea in the 1470s, nor did the presence of Atlantic designs in the western Mediterranean stop North African corsairs from constantly raiding Christian shipping.

(But I should be writing part 2 now.)

Doug M.

Doug Muir 02.23.26 at 6:31 pm

J-D @20, I’m pretty sure the comparison has been done, and it favored the Ming — though that might be the effect of fewer languages and a larger single market.

Phil @21, the Normans, Plantagenets, Tudors and Stuarts all ran out of direct legitimate male heirs. (For the first two, their habit of murdering each other didn’t help.) As I noted in a previous post, horrific infant and child mortality rates — including for royalty — meant that you were lucky to get a couple of legitimate kids surviving to adulthood. So the odds were pretty good that sooner or later you’d get a generation with no boys.

In the last couple of centuries, this has become much less of an issue. So the Hanoverians do have a living legitimate male heir: Ernst August von Hannover.

Doug M.

Tm 02.23.26 at 9:24 pm

OP: „Portugal — a kingdom small and obscure even by medieval European standards“

A nitpick but that statement sounds odd to me. I don’t know whether contemporary Europeans would have considered Portugal “obscure” (from whose perspective anyway?) but size is an objective fact, and afaik there weren’t many European states at the time (c. 1400) significantly larger than Portugal. Probably just Poland-Lithuania, Hungary, Castile, France (but hardly a unified country at the time), Sweden. Even England (without Scotland and Ireland) was (and is) not much bigger. Btw the alliance between England and Portugal dates from 1386, so Portugal wasn’t quite hidden (obscure) from the rest of Europe.

An aside, it seems Portugal is the only European state that has kept the same territorial size and shape and borders since the Middle Ages, that is more than 700 years. From Wikipedia: “Portugal’s land boundaries have been notably stable for the rest of the country’s history. The border with Spain has remained almost unchanged since the 13th century.”

Tm 02.23.26 at 9:51 pm

Peter 6: “Basically, if you were a recognised kingdom in Europe by 1100 you were still there in 1900”

Another statement that strikes me as odd. If you look at a map of medieval Europe and compare it to a modern one, or one from 1900, there is very little similarity. The medieval kingdoms of Aragon, Castile, Catalonia, Naples, Sardinia, Sicily, Burgundy, Scotland, England all disappeared (as states, not as cultural entities) and most states existing today didn’t exist (as states) in medieval time.

J-D 02.23.26 at 10:07 pm

No! England has never had an explicit rule excluding women from the succession.

What there was until very recently was a rule giving a younger brother precedence over an older sister, but that’s not an exclusion of women.

J-D 02.23.26 at 10:15 pm

In the last half-millennium the line of legitimate patrilineal descent from James I (the Stuarts) ran out (although its last representatives had already been excluded from the succession on religious grounds). Before that the line of legitimate patrilineal descent from Henry VII (the Tudors) ran out; and earlier the line of legitimate patrilineal descent from Henry II (the ‘Plantagenets’) ran out; and earlier still the line of legitimate patrilineal descent from William I ran out. Going back even further, it turns out that the line of legitimate patrilineal descent from Alfred the Great ran out, although its last representative had in any case been ousted by the Norman Conquest.

J-D 02.23.26 at 10:20 pm

So when did that turn around?

Also, if it favoured the Ming in the fifteenth century, by how much? And was Europe second, third, what?

Tm 02.23.26 at 11:01 pm

Since this seems to be the place for amateur historian musings, forgive me another remark:

The map raises the question why “small, obscure” Portugal wasn’t, along with Castile, Leon, Aragon and Catalonia, integrated into the Spanish kingdom. Wouldn’t that seem natural (and efficient) – a small country with a big neighbor with similar language and history? Why wasn’t it attempted (or if it was, why didn’t it succeed) to unify Iberia under a single crown, by marriage or if necessary by force?

It’s another example that history doesn’t work the way the so-called foreign policy realists think it works – big fish eating small fish. Sometimes the small fish get eaten but often they don’t. Otherwise there wouldn’t be so many small fish still around.

Tm 02.23.26 at 11:07 pm

Regarding J-Ds question, it may be relevant that some (or all?) Muslim rulers banned the printing press. That definitely hampered their intellectual exchange, which earlier had been more robust in the Muslim world than in Christian Europe.

Peter T 02.24.26 at 1:39 am

tm: Aragon has a different tax regime even today, Catalonia was part of Aragon, Scotland retained independence in the law, education and religion even under the Act of Union (ie it was recognised as a legally separate entity in key areas), the Kingdom of Italy kept a shadowy existence, Burgundy was either an appanage under the French crown (Duchy Burgundy), part of the Empire (County Burgundy) and a a collection of counties under one or the other (Flanders, Holland, Zeeland et al). Pre-modern states had much less central control and sub-units more room to manoevre, but the overall concept of, say a Kingdom of France or an Empire with the royal or imperial courts as the ultimate arbiter retained considerable meaning even in the loosest periods.

There are exceptions and pre-modern polities with their overlapping jurisdictions, conjoined rulers and fuzzy boundaries are hard to map precisely, but European states have an astonishing history of competitive endurance compared to other parts of the world.

Peter T 02.24.26 at 2:59 am

Doug

On cannon – used with effect at the Battle of Crecy (1346), and siege of Calais (same year). Wikipedia notes Petrarch (1350) that cannon were ‘as common and familiar as other kinds of arms.

I’ll use the occasion to recommend Tonio Andrade’s The Gunpowder Age, which delves into the different trajectories of gunpowder weaponry across Eurasia.

On ships – you neglected the Venetian ‘great galleys’, which made round trips between Flanders and Venice. My comment was less on naval warfare than commerce. Yes, the Ottomans could mop up Venetian and Genoese holdings in the eastern Mediterranean and hold their own in the Red Sea (fascinating diversion into successful Portuguese assistance to the Kingdom of Abyssinia, despite Ottoman help to the Sultanate of Harar). They had no equivalent to the humble cog rapidly integrating commerce from the Baltic to Sicily: cheap, low operating cost, able to handle both the North Sea and the Adriatic.

MisterMr 02.24.26 at 10:34 am

About cannons, here there is a blog post by Brett Deveraux about the history of fortifications, and specifically on the impact of cannon technology in Europe between 1300 to early 1500, in particular it seems that european castle-walls were built in a way that was particularly weak to big cannonballs (they were high and thin), so at some point Charles VIII of France wages war in Italy in 1494 with more powerful cannons and smaps everyone because he can destroy in days fortresses that previously took months, which in turn leads to a specific arms race in Europe.

LFC 02.24.26 at 11:53 am

Re Burgundy:

From the 1380s and for roughly the next hundred years (until 1477), Valois Burgundy, encompassing the duchy and county of Burgundy as well as Flanders (and other parts of the Low Countries), was a formidable power, and the duke of Burgundy in the mid 15th cent was, in the words of one historian (M. Gilmore), “undoubtedly…the most considerable political power in western Europe.” Significant bc it had v. non-contiguous territories and was nonetheless a major geopolitical force.

engels 02.24.26 at 12:29 pm

why “small, obscure” Portugal wasn’t… integrated into the Spanish kingdom… It’s another example that history doesn’t work the way the so-called foreign policy realists think it works – big fish eating small fish

Ahem. Portugal was part of the Umayyad caliphate and then the Kingdom of Leon along with much of modern Spain. Long after independence it was reabsorbed in the Iberian Union of 1580.

Realists don’t think “big fish eat small fish” but as a colonial power with a vast empire Portugal was only a “small fish” in the sense that, say, Victorian Britain was.

Apart from that, Mrs Lincoln, how did you enjoy the point?

marcel proust 02.24.26 at 2:01 pm

TM@30: Portugal was united with Spain for 60 years in the late 16th-mid 17th century following a dynastic crisis. Spain treated Portugal essentially as a defeated enemy, and when the Spaniard’s Flemish subjects were busy throwing off the Spanish Yoke, Portuguese nobility saw an opportunity to do the same.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Portugal#1580_succession_crisis,_Iberian_Union_and_decline_of_the_Empire

According to google’s AI, the only parts of the Iberian peninsula that were not part of Aragon or Castile in 1479 at the time of the 2 kingdoms union under Ferdinand and Isabella were Granada (conquered in 1492), Navarre in the north (the area south of the Pyrenees was conquered shortly thereafter in 1512*) and (wait for it) Portugal.

*The king of Navarre inherited the French throne in 1589 and it became part of France in 1620.

steven t johnson 02.24.26 at 3:09 pm

Re the longevity of some dynasties (Romanovs and Habsburgs?): A wonderful tale of potent husbands and faithful wives?

engels 02.24.26 at 6:43 pm

Re the longevity of some dynasties (Romanovs and Habsburgs?): A wonderful tale of potent husbands and faithful wives?

Undiscovered infidelity might be more realistic.

Alex SL 02.24.26 at 8:08 pm

Doug Muir @16,

That is why I wrote “argument I have seen” and “the commonly told story” instead of stating it as fact. My own hunch is generally that technology, logistics, resources, and numerical superiority matter much more in history than one-off political decisions or institutional arrangements.

Tm 02.25.26 at 12:36 pm

Thanks for the remarks about Portugal. I relied in Wikipedia and my historical Atlas, which both indicate that the present day borders were established by the 13th century and remained unchanged ever since. That Portugal became a world power in the 16th century is of course relevant but doesn’t explain why Portugal exists in the first place (that’s a historic contingency which cannot really explained imho).

Didn’t know about the union with Spain but obviously it was short-lived. There was also a union between Denmark and Sweden, also short-lived. Poland-Lithuania persisted for centuries but finally disappeared, its parts eaten by what at the time were bigger fish, but nowadays several parts exist as independent states. Other union have formed (Germany, Italy, Switzerland), others have broken up.

Regarding Scotland, Catalonia etc, they still exist as cultural entities and with a measure of self-governance, but not as independent states although this might change again. Burgundy was not just a powerful duchy in the 15th century; it was actually a kingdom around the 11th c, which is why I mentioned it. At the time it was formally part of the Holy Roman Empire.

What all this is meant to prove? Really just that history is contingent and almost everything is possible.

Tm 02.25.26 at 1:09 pm

To be clear, Burgundy the medieval kingdom and Burgundy the early modern Duchy/wannabe European power were completely different entities on different territories, and the modern region Bourgogne has little to do with both. And of course they have little to do with the 4th and 5th century Burgundians, even less with the mythical Burgundians of Nibelungenlied fame. Names are deceptive.

J-D 02.26.26 at 3:35 am

Is it possible that literacy and book production/circulation in Europe surged ahead of China because of the invention of movable type? The printing press was invented in China and Europe imported it but movable type was a European innovation, and one which offers much bigger advantages when working with European writing systems than when working with Chinese writing systems. I suppose this raises the question of why China and Europe had such different writing systems.

engels 02.26.26 at 11:08 am

…which was obviously the joke (duh).

Alternative answer to why the big fish aren’t gobbling up the small fish (they already have).

Nachasz 03.09.26 at 12:31 pm

@steven t johnson

Romanovs do not seem to be a particularly good example of dynastic longevity, especially if compared to Habsburgs.

Doctor Memory 03.09.26 at 2:39 pm

Please ignore this; I’m coming back around to the CT cleanup project and wanted to test something:

‘straight single quotes’

“straight double quotes”

straight backticks“Smart double quotes”

‘smart single’

“Smart double ‘smart single’ quotes”