I heard a rumour that London IT professionals have selected the pub where they will meet when the internet goes down.

It is apocalyptic thinking, perhaps, but it also feels plausible. Though the internet feels permanent, stable and sufficiently distributed to seem impervious to target, this infrastructure that underpins our daily work and life is strikingly vulnerable. Undersea cables get damaged; phone and cable systems go down; and software is frequently corrupted or hacked.

A backup plan is sensible. It matters because they might be the only ones who know how to rebuild the internet – and they need a way to contact one another.

Perhaps we also need a pub at the end of the university?

Image: I asked ChatGPT to create a picture of scholars in a pub during the apocalypse. I see chatty didn’t think there would be any women.

The End of the University?

I don’t seriously believe that the university will end any time soon. Though I do think that they have been very seriously weakened and are not presently up to the tasks that confront higher education now, which might almost amount the same thing.

Coming home to roost in universities around the world are the consequences of unbearable austerity, especially in relation to teaching, matched only by unforgivable profligacy by (and for the benefit of) a managerial class. Under their watch, and following two decades of unprecedented and exponential enrolment growth, some universities are at risk of bankruptcy, while others are cutting staff at a rate that bears no resemblance to any decline in the importance of university teaching or research. I hear that 15,000 academics have lost their jobs in the UK, just this year.

Things in universities are not great in other ways, either. Study is burdensome rather than enlivening. Teaching is performed under conditions that make it impossible. Research is measured in ways that interfere with its direction and undermine its pleasures. Management, sometimes but not only in response to governments trying to ensure management are doing what they were paid for, in turn impose so many compliance and performance measures on teachers, researchers and professional staff that it is getting hard to get much done at all.

Sustained attacks from the far right, who fear places where young people might be exposed to ideas that threaten their narrow, nasty world view, have destabilised the possibilities for a tertiary system that seeks a more equal, more inclusive world. Their alignment with powerful capitalist interests is obvious in 2025: and so too is university management’s, every time they relinquish ground.

This means that at the very moment that environmental catastrophe, energy transitions, and threats to the discernment of truth (via multiple vectors: AI, geopolitical, social media-radicalism, conspiracy-theory populism, incel and cooker self-promotion) let alone massive industry demands for the skills universities produce (yes in HASS too), these glorious and flawed institutions are sadly crippled.

The Work is Amazing

And yet, amazing work is still being produced. You really see it working for government. Lots of applied and theoretical work on nearly every issue emanates from universities. It is incredibly useful. Want to know about the economics or logistics issues related to the housing crisis? The cost of living crisis? Want to understand the teaching shortage? Need a philosophical framework for men performing care work? Want to consider the value of emotional labour? Concerned about the current state of democracy? Need ideas for reforming…pretty much anything, really? It is all there, though the system is clearly teetering, students may not be learning – or worse, having any fun – and the best intellectual talent is being pushed out. 15,000+, good lord.

Universities provide the fundamental infrastructure for decision-making in industry and government. And they provide the tools for bolstering democracy – indeed, this was what the systems we have inherited from the post-war moment were largely for. They are precious and amazing places, and being able to do that work is a gift – if you can get it done under excessive managerial surveillance, which fundamentally inhibits creativity.

It is great to do this in a university because good thinking, like most good work, is best done with other people. It is all very well for me to read, take notes, listen to podcasts and write my ideas. But those ideas are so much better when I also talk about them over drinks, in seminars and conferences, or in the corridor. This is also why for decades universities kept class sizes small enough to ensure all these new and emerging thinkers had opportunity to talk, listen, debate and (re)consider what they thought they knew. It is just not possible for all 30 (or 60!) members of a tutorial to speak, so we know that few get that experience any more.

It is a particularly tragic loss when academic staff are pushed out of the spaces where this work happens. Every one of the approximately 15,000 lost academics in the UK was producing work, teaching students, and engaging with the industries and communities that inspired or will use their work. But now they are not. We mourn their loss.

The message as always is that it is not your fault. It was (mis)management. And management has to go, not the academic and professional staff doing the work.

We don’t need them. But we do need you.

Academia and Identity

This is a problem for those whose identities are fundamentally entangled with higher education. Many academics feel singularly unequipped for any other job (I don’t believe this is true, but it certainly feels that way for many). More, they trained so hard, for so long, sacrificed so many things and loved their work so deeply that the grief associated with losing a place in the academy seems unbearable.

This was partly why management and their metrics can wield fear like a sniper on the roof. Fear inhibits good work, but it also increases managerial power. I can hardly express how wonderful it is to shed it.

It was much harder, however, to relinquish my identity as an academic. That is still a work in progress, truthfully.

It is hard to leave a cult.

But also. Academia is a cult

A thousand subliminal messages tell us that good scholarship and hierarchical academic esteem are co-dependent. RF Kuang’s Katabasis captures it well. The main characters are prepared to relinquish half of the days they have left to live for a shot at academia. They regularly say they would ‘rather die’ than leave the university. Being and feeling included in the ‘life of the mind’, she has her characters observe, requires an academic job (IRL conversations people in my world just refer to it as ‘a job’ as if it is the only kind).

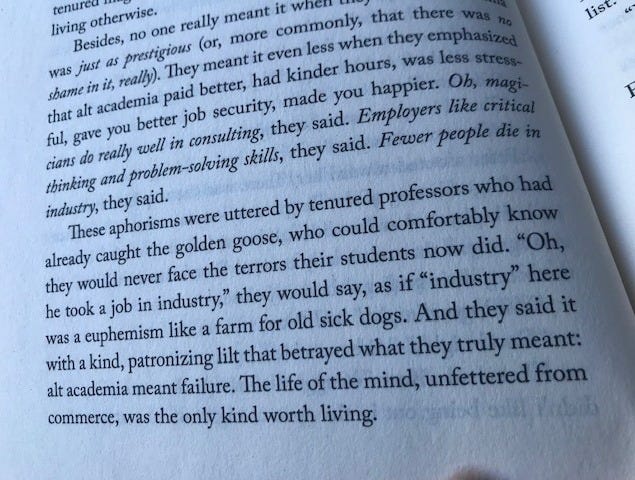

“Oh, he took a job in industry”, they would say, as if “industry” here was a euphemism like a farm for old sick dogs. And they said it with a kind, patronizing lilt that betrayed what they truly meant: alt academia meant failure.

Image from RF Kuang’s Katabasis including above quote.

To be frank, this is bullshit.

An upside is that fewer people ask you to complete the worst of the academic chores.4

I hope in time that scholars in and out of the system see that good scholars and intellectuals – 15,000+ in the UK alone – may work outside of the university, but are still colleagues in every other sense.5

Indeed, given the state of the world, it might actually be transformative to have such high quality, well-trained thinkers becoming embedded in a wider range of workplaces and communities – without losing engagement with their scholarly colleagues and disciplinary organisations (unless they choose that ofc). And that work will in turn inform and transform scholarship in valuable ways.

We should fix universities, of course. To do that we mostly need the managerial class to get out of the way. They are not keen on losing this power and some are even talking about taking a pay cut so they can stay in control.6

The pub at the end of the university

More importantly, the weakened state of the universities surely compels us to consider what might be our ‘pub’ where we meet to rebuild intellectual life as the university goes down.

Even though the university won’t exactly ‘go down’ in the way the internet might, it just may not be in a good position to face the challenges this emerging phase of f*cking capitalism looks likely to throw at us.

At the pub at the end of the university, away from managerial surveillance and control, we might really start to build something that is democratic in purpose and structure – actively inclusive, boldly truthful and protective of democratic systems, engaged with people, communities and workplaces in ways that are creative and enlivening. Transforming and rebuilding the world with ideas.

{ 0 comments… add one now }