You searched for:

too like the lightning

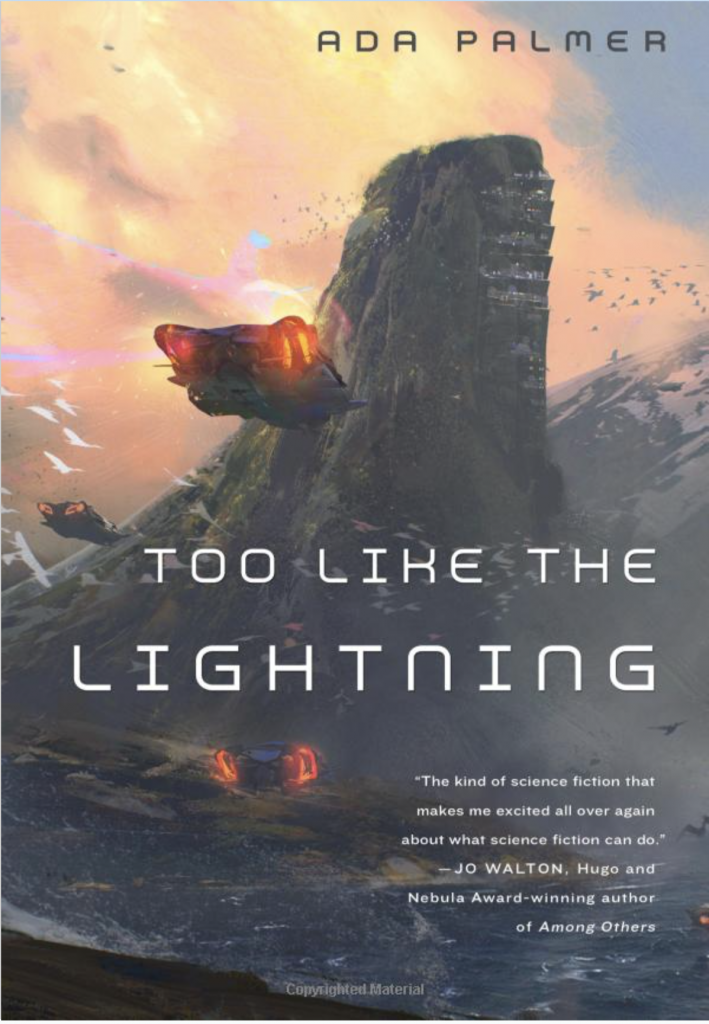

Ada Palmer’s Too Like the Lightning is finally out (Powells, Amazon), so that you can read it too (I’ve been impatiently waiting to share it with everyone I know). As Jo Walton says here, it’s wonderful. It does something that I think is genuinely new (or at least, if other people have pulled it off, I haven’t read them). Palmer is a historian (here’s an interview I did with her on her book about Lucretius’ reception in the Renaissance) and approaches science fiction in a novel way. Her 25th century draws on the ideas of Enlightenment humanism, but in the same ways that, say, America draws on the writers of the Declaration of Independence and the Federalist Papers. Which is to say that it takes the bits that seem useful, reinterprets them or misinterprets them as new circumstances dictate, and grafts them onto what is already there, throwing away the rest. Palmer does this quite thoroughly and comprehensively – her imagined society is both thrown together in the way that real societies are, and clinker-built (in the sense that she has evidently really thought through how this would be related to that and what it might mean). [click to continue…]

Reappropriated Histories

a response to Neville Morley, “Future’s Past.”

I was very excited looking forward to a classicist’s response to these books, and very satisfied that the references to antiquity loomed large for him as I expected. My use of the Enlightenment is intentionally conspicuous, even ostentatious, throughout the book. Antiquity is a quieter presence, but still, as Morley observed, deeply pervasive, in the Masons, and in Mycroft’s own thought and imagery.

I actually worked in an intentionally cumulative momentum to the presence of antiquity in the book, and especially the presence of the Iliad, as Mycroft’s references to Homeric imagery become more frequent, and as his use of grand Homeric similes become more frequent and more explicit over the course of the first two books. Ganymede is the Sun in the first book but Helios in the second, and the first time dawn has “rose fingers” as she always does in Homer is the morning of the Sixth Day of Mycroft’s history, the irrevocable day when civilization’s rose-tinted daydream breaks. This momentum builds toward the revelations of the book’s end, both the final revelation in the chapter “Hero,” and final solidification of that word which Mycroft begs Providence not to bring into his history: war. Like many subtle writing things, I don’t expect most people to be conscious of it, or for it even to have a strong effect on everyone, but especially for a classicist its presence was intended to add a more epic feeling as momentum built, and to make the end of Seven Surrenders feel, not predictable, but correct, as when a long, elaborate algebraic exercise yields a solid 1=1. [click to continue…]

The seminar with Ada Palmer on Seven Surrenders and its prequel, Too Like the Lightning is now complete. Below, a list of the participants with links to their individual posts, to make it easier to keep everything together (a PDF will be forthcoming). All posts are available in reverse chronological order here. Comments should be open, for anyone who wants to talk about the seminar (or the books) as a whole.

The participants:

* Ruthanna Emrys is author of the novel, Winter Tide. Falling into the Cracks of Identity.

* Henry Farrell blogs at Crooked Timber. De Sade, War, Civil Society.

* Maria Farrell blogs at Crooked Timber.In Good Hands.

* Max Gladstone is the author of the Craft Sequence books (see here for his interview on how James Scott’s _Seeing Like a State_ can be a great starting point for a f/sf series).The Old Dragon But Slept: Terra Ignota, the Sensayer System, and Faith.

* John Holbo blogs at Crooked Timber. Heroes and Aliens.

* Lee Konstantinou is an assistant professor of English Literature at the University of Maryland, College Park.Ada Palmer’s Great Conversation.

* Neville Morley is Professor in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Exeter.Future’s Past.

* Jo Walton is the Hugo Award winning author of many books (and subject of a previous Crooked Timber seminar).Complicity and the Reader.

* Belle Waring blogs at Crooked Timber. Gods of This Fictional Universe.

* Ada Palmer is an Assistant Professor of Early Modern European History at the University of Chicago.

The Dystopian Question and Minorities of One [Response to Emrys and Gladstone]

Reappropriated Histories and a Different Set of Tools [Response to Morley and H. Farrell]

Unusual Experience and Second Hand Plato [Response to M. Farrell and Waring]

Not Nothing and Speculating Late [Response to Holbo and Konstantinou

A Dialog on Narrative Voice, Complicity, and Intimacy [Dialogue with Jo Walton]

{ 10 comments }

Between Jo Walton and Ada Palmer.

Continuing from Jo’s essay “Complicity and the Reader”

Jo Walton is a good friend, and there is little we love than sinking our teeth into a fascinating aspect of the craft of writing. We’ve discussed questions of narration, voice and complicity in Terra Ignota many times, so much so that much of what I would say in response to Jo I already have, and she’s already addressed it in her essay. So I thought that the best way to bring something really new, and to round out this delightful seminar, was to have a fresh dialog with Jo about the subject, and to share it—in all its rawness and discovery—with you. And once again, thank you all for reading so deeply, thinking, discussing, sharing your thoughts, responding, and reading more—discussion like this seminar the happiest fate that can befall a book. And an author. [click to continue…]

The “Not Nothing” in Thomas Carlyle’s Protagonization of History

a response to

John Holbo “Heroes and Aliens”

John Holbo’s essay is a masterwork of hinting without revealing, discussing pieces while keeping the veil across the whole. As I read it, a visual kept entering my mind, of great hands reaching under the belly of a Leviathan, lifting it toward the ocean surface, not high enough to expose its shape or color, just enough for the many reefy knots and house-sized barnacles that stud its skin to poke up through the dark waves like an island chain, so the spectator on the shore can just make out that there is a living vastness in the deep whose structure connects makes many new-bared lands one.

My first contact with Carlyle’s Heroes, Hero Worship and the Heroic in History came suddenly, in my second year of grad school. The title lurked on my list of required historiographical background reading, preparation for my oral exams, amid so many histories of Italian city-states, and rebuttals of Hans Baron. My cohort and I were wolfing down a book a day in those months, looting each for thesis and argument, so we could regurgitate debates, and discuss how our own projects fit with the larger questions of the field. Only two books refused on that list to be so digested: Carlyle’s, and Burkhardt’s The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. [click to continue…]

Unusual Experience

a response to Maria Farrell “In Good Hands”

I love micro-autobiography. I love autobiography too, but micro-autobiographies like Maria Farrell’s essay here, a closely-narrated experience in which you get to know a new human being through what that person shares about a small, relatable experience of real time, are just so tender, and intimate, celebrations of the art that goes into every tiny part of being human, like the little hidden faces tucked between the tracery of a gothic archway, through which the architect shares with every visitor a small slice of play. That’s why my favorite thing, when I meet a new person who has read Too Like the Lightning is to say nothing beyond some periodic approving “oohs” so as not to interrupt the beautiful flow of this new reader’s unique and beautiful experience. [click to continue…]

The Dystopian Question: Is There a Place For Me?

a response to

Ruthanna Emrys “Falling Through the Cracks of Identity”

I was delighted to see Ruthanna touch on a number of the tensions within the Hive system that I crafted intentionally, and am setting up for further resolution in the second half of Terra Ignota. The Utopian’s isolationism, the pressure of those caught between Hives as personified by Cato Weeksbooth, and the particular awkwardness of the Cousins having what feels like a forced politico-cultural monopoly on caregiving and such huge slices of our society, and our curiosity about the Hiveless.

I was interested to see the characterization of Hiveless as “second-class citizens” and the assumption that they don’t participate in government, or inform the laws that govern them. Such guesses do indeed follow reasonably from what’s in the first two books, particularly since Mycroft makes so much of Hive power, so I’m very excited to see how Ruthanna and other readers expand their impressions of the three Hiveless groups on Book 3, when we see a lot more, both of them and of how they’re integrated into the politics of Romanova. In the first books we hear hints in that we know J.E.D.D. Mason is, among other things, a “Graylaw Hiveless Tribune” but we don’t know yet precisely what that entails, or just how powerful the Hiveless Tribunes are within the Alliance. [click to continue…]

Around a third of the way through the first book of Terra Ignota, Too Like the Lightning, we finally learn something of substance about the philosophy of the Utopians, one of the seven global Hives that dominate the Earth in Ada Palmer’s imagined twenty-fifth century.

There were hints before, but the truth finally struck me when Mycroft Canner meets two oddly named Utopians: Aldrin Bester and Voltaire Seldon. “Aldrin Bester,” Mycroft informs us in an aside is “a fine Utopian name lifted from their canon, as in the olden days Europe took its names from lists of saints.” The Utopians’ canon, of course, is the canon of science fiction. Voltaire belongs in that canon, Mycroft scrupulously reminds us, because of his 1752 novella “Micromégas,” which “makes him a candidate for the title of world’s first science-fiction author.” The Utopians, it turns out, are SF fans of the future, organized into one of the most powerful political organizations on the planet. A few years ago, Neal Stephenson called for a return to the “techno-optimism” of Golden Age and space age science fiction, expressing fears that we now live in “a world where big stuff can never get done.” (Where are our flying cars?) Palmer’s Utopians have turned Stephenson’s lament into an ideology, a way of life, and an identity. They control the Moon. They’re planning to colonize Mars (which turns out to be something of a big real estate grab, a threat to Mitsubishi, which owns most of the Earth). But more importantly, the Utopians are avatars of the imagination, ideologues of the future. [click to continue…]

“I am like a being thrown from another planet on this dark terrestrial ball, an alien, a pilgrim among its possessors.” – Thomas Carlyle [the real one, from an 1820 letter]

“So there I was, thinking: is this a space alien? Is this kid insane?” – Too Like The Lightning

‘¿How is the world weird lately?’

< you wouldn’t understand. > – Seven Surrenders“You know I’m sincere, Caesar, in my way. I love the Eighteenth Century. I fell in love reading about it at the Senseminary, that great moment when humanity realized experiments didn’t just have to be done with the sciences, they could be done with morals and religion, too. I wanted to do that, run an experiment like the American experiment, or greater. I couldn’t resist the chance to finish what my heroes started, not just the humanitarians like the Patriarch and the Romantics like Jean Jacques, but the underbelly, La Mettrie, Diderot, De Sade. The Enlightenment tried to remake society in Reason’s image: rational laws, rational religion; but the ones who really thought it through realized morality itself was just as artificial as the artistocracy and theocracies they were sweeping away. Diderot theorized that a new Enlightened Man could be raised with Reason in place of conscience, a cold calculator who would find nothing good or bad beyond what his own analysis decided. They had no way to achieve one back then, but I did it. I raised an Alien.” – Seven Surrenders

This post will be something like a Thomas Carlyle style sampler – (un)commonplace book – for potential readers of Ada Palmer’s Terra Ignota novels. (You’ve never read Carlyle? That’s quite normal! We shall remedy the defect, slightly.) The Palmer-related point will be something like this. These novels are great! But very weird. She writes like she thinks she’s … Thomas Carlyle or something. That, or I don’t know what. (She doesn’t mention Carlyle by name in her “Author’s Note and Acknowledgement”, but she keeps naming characters after him.)

I don’t propose this as some secret key to the novels. I am sure there is no one Code at the root of it, waiting to be named ‘Carlyle’ (or anything else). But I am only one voice around the table here, so I hope a spot of overemphasis shall not be taken amiss. (Seldom have I read sf novels with so much philosophy packed in, which I’m not inclined to describe as having a philosophy, or being attempted thought-experiments. I mean that in the nicest way.)

I myself have a bit of a Carlyle bug in the ear — sf related one, even. When I teach “Philosophy and Science Fiction” I talk about H.G. Wells, The Time-Machine. (By the by, I must mention that Adam Roberts has been tearing it up, Wells-wise.) I talk about why there’s a sphinx. I talk about Oedipus and the Riddle. I have a bit to say about how maybe Thomas Carlyle, Past and Present — that chapter, “The Sphinx” — is of interest to students of the history of science fiction. Cosmic vision of looming, long-term Truth behind curtain of present life!

“How true … is that other old Fable of the Sphinx, who sat by the wayside, propounding her riddle to the passengers, which if they could not answer she destroyed them! Such a Sphinx is this Life of ours, to all men and societies of men … Nature, Universe, Destiny, Existence, howsoever we name this grand unnameable Fact in the midst of which we live and struggle, is as a heavenly bride and conquest to the wise and brave, to them who can discern her behests and do them; a destroying fiend to them who cannot. Answer her riddle, it is well with thee. Answer it not, pass on regarding it not, it will answer itself; the solution for thee is a thing of teeth and claws … With Nations it is as with individuals: Can they rede the riddle of Destiny? This English Nation, will it get to know the meaning of its strange new Today? Is there sense enough extant, discoverable anywhere or anyhow, in our united twenty-seven million heads to discern the same; valour enough in our twenty-seven million hearts to dare and do the bidding thereof? It will be seen!—”

We have Nietzschean science fiction, of course; Hegelian science fiction — Olaf Stapledon oughta hold you. Why not Carlyle-style sf?

Let’s start with my epigraphs, above. [click to continue…]

{ 7 comments }

Time again (seeing as nominations close in a couple of days), for Hugo nominations suggestions, or, more precisely, an excuse to briefly talk about books that I read in the f/sf genre last year and liked a lot.

*Best Novel*

* Ada Palmer – Too Like the Lightning. Enough being said around here already.

* Paul McAuley – Into Everywhere. People in the US don’t read McAuley nearly as much as they should. This, together with his *Something Coming Through*, is as good as straight science fiction gets these days. I didn’t like M. John Harrison’s Kefahuchi Tract books nearly as much as his other work – these two books are less ambitious, but seem to me to capture better some of what Harrison was trying to do, in using near- and middle-far future science fiction to get at the tropes of consumer society. Sharp, drily funny if you read closely, and does for *Childhood’s End* what his Confluence books did for *The Book of the New Sun.* There is infinite hope, but not for us. If you haven’t read any McAuley, try his short story Reef, available for free online. If it gets on with you, the rest probably will too.

* Dave Hutchinson – Europe in Winter. Again, I don’t think Hutchinson gets the attention he deserves in the US. But this – and the other two books before – are really quite brilliant about Europe, and England’s complicated attitudes to it. The first book, *Europe in Autumn* is still my favorite of the three, but this is extremely good too – spies, a Europe that has split up into hundreds of odd microstates, and an alternative universe in which the Home Counties have extended in a manner both sinister and avuncular to take over large parts of the globe.

* Sofia Samatar – The Winged Histories. I really liked this for its combination of large scale politics and small scale personal history. It reminded me (despite differences in writing style, subject etc) of Maureen McHugh’s wonderful *China Mountain Zhang* in the interest that it takes in people’s lives.

* Max Gladstone – Four Roads Cross. The latest in his Craft sequence of novels, which is available in its entirety for $12 on Kindle – a bargain that you probably won’t regret. Enormous fun, but also very interesting in its take on the politics of globalization (the previous book, *Last First Snow* very deliberately takes on the question of how the insights of James Scott’s Seeing Like a State could be transferred into a fantasy setting).

Also, two books that I *don’t want* to see nominated for Best Related Work, if only because they were both published in the UK in 2016, and US in 2017, and probably have better chances next year.

* Edmund Gordon – The Invention of Angela Carter. I’ve loved Carter’s work since I first came across it – she’s one of the very few supserstars whom I would have loved to meet (I remember plotting as an undergraduate to go to a talk that she was going to give in Dublin; it was cancelled at short notice, because of what turned out to be her final illness). It’s surprising that we’ve had to wait so long for a biography, but this is a really quite wonderful one. It isn’t at all hagiographical (as the title suggests, she happily reinvented facts about herself and her family to come up with an identity that she felt she could get on with), but it conveys her strength, her intelligence, her contrariness and her warmth. I hadn’t realized that David Hume was such an influence on her work (not having read the novel that takes an epigraph from him), nor would I have ever suspected that William Trevor was an admirer of Carter’s work, given their differences of subject matter and style. If Carter wasn’t often formally identified as a genre writer, she was emphatically a fellow traveller, whose work both spoke to fantasy and borrowed from it.

* Mark Fisher – The Weird and the Eerie. I only figured out who Mark Fisher was after he died last year. I’d read a couple of pieces he had written (especially his interview with Burial), and encountered many of his ideas at second hand, without ever properly realizing that there was a single person behind them. Now, I’m very sorry. This is a wonderful, odd, individual book, which brings together Alan Garner, the last series of Quatermass, M.R. James and others. I desperately want to argue with him, and write at him (it seems to me that his concept of the eerie is very helpful in understanding aspects of *Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell* which isn’t nearly as cosy as it appears to the superficial glance), but can’t.

As always, feel free to carp, disagree and (especially) make other suggestions for books worth reading in comments.

You know that feeling about fifty pages into a novel you can tell you’re going to get along with? When you’re confident the various elements – character, plot, style – are going to be handled well, and the material is the right mix of familiar and challenging. When it’s about things you just find interesting. It’s quite a rare feeling, as an adult reader. It’s a call back to the cocooned and all-encompassing stimulation in the embrace of the books William Gibson calls a person’s native literary culture. That mix of feeling held and also working quite hard at it, but happily so. I had it recently, reading Becky Chambers’ The long way to a small, angry planet*. It was such a strong feeling that I took a pencil to write ‘in good hands’ in the margin.

You know that feeling about fifty pages into a novel you can tell you’re going to get along with? When you’re confident the various elements – character, plot, style – are going to be handled well, and the material is the right mix of familiar and challenging. When it’s about things you just find interesting. It’s quite a rare feeling, as an adult reader. It’s a call back to the cocooned and all-encompassing stimulation in the embrace of the books William Gibson calls a person’s native literary culture. That mix of feeling held and also working quite hard at it, but happily so. I had it recently, reading Becky Chambers’ The long way to a small, angry planet*. It was such a strong feeling that I took a pencil to write ‘in good hands’ in the margin.

I had the ‘in good hands’ feeling by page three of Too Like the Lightning (TltL). It begins at a brilliantly chosen moment of crisis that introduces great characters on the horns of a dilemma that underpins the story; how does a studiedly irreligious society cope with a miracle? TLtL also has a sweet boy, both old and young for his age, with an utterly magical power. Bridger can make objects or drawings real, be it into living creatures with all the characteristics of ensoulment, or horrifying abstract concepts with the ability to end the world. [click to continue…]

{ 16 comments }

First let me say that I recommend Too Like The Lightning and Seven Surrenders to all of you quite fervently; they are the best sci-fi books I have read in ages. John says they are weirder than Miéville, though I’m not sure about that. Less weird than Clute’s Appleseed, anyway (what isn’t?). Second, I am going to talk about both books, though not indifferently, because they are more like the continuation of a single book than most originals and sequels. Third, I am about to reveal what I consider the antepenultimate spoiler for Seven Surrenders. That is, there are two, yet more shocking revelations/events that follow this one—and to be absolutely fair the main point I discuss was quite clearly stated in Too Like The Lightning, but in a way difficult to credit. There are many other spoilers too though, so, if you don’t like spoilers you will hate this and you should not read it.

SPOILERS FOLLOW GEE WHIZ THAT’S AN UNDERSTATEMENT, BELLE WARING.

[click to continue…]

{ 12 comments }

*Too Like the Lightning* and *Seven Surrenders* tell the story of beautiful, brilliant, compassionate people who are also terribly vulnerable. They are Eloi who have convinced themselves Morlocks do not exist; they are victim-beneficiaries of two hundred years of willful ignorance of growing rot. Like the dragon Smaug, they’ve rested on their hoard for centuries, adding layer after layer to their invulnerable bejeweled armor—but they cannot see the armor’s chink, the soft space waiting for Bard the Bowman’s arrow.

The arrow is shaped like God.

[click to continue…]

{ 12 comments }

> In the five million years following the Great Nebula Burst, our people were one people. But then came the Zactor Migration, and then the Melosian Shift and a dark period of discontent spread through the land. Fighting among Treeb sects and Largoths. The foolishness! And it was in this time of dissension … *

Almost all science fiction, as J.G. Ballard remarked in the introduction to *Vermilion Sands*, is really about the present day. This is certainly less true today than it was in 1971, but it is still often the case that the relationship between our present and the future world that is depicted – or between the present of the imagined world and that future’s past, when anyone inside the story decides to look back – is oddly straightforward and uninteresting. This is certainly not something that can be said of Ada Palmer’s *Terra Ignota* books.

Why look back to the past when we’re interested in the future, or spend any time considering the less developed form of that future? Sometimes, especially in the case of film franchises desperate to keep an existing audience happy with something that’s new but not too different, it’s just a matter of expanding the known universe by answering some questions that weren’t actually in need of answering – how did humanity come to develop the warp drive and conquer the stars, why did the Rebellion start? – with varying degrees of success. The resultant products offer their consumers the usual fare of time travel stories or historical novels: the thrill of recognising the germ of a familiar artefact or institution, or the ancestor of a familiar character, or other nuggets of intertextuality. In most cases there is little or nothing at stake; we know where things are going, so this is just a matter of filling in the gaps between then and now. [click to continue…]

In the genres of science fiction and fantasy, when a book is written in an unusual mode, it’s usually either a gimmick or window-dressing. Window-dressing is when for instance a Victorian feeling book has a faux Victorian style as part of that feel. An example of this would be Heinlein’s *The Moon is a Harsh Mistress,* where Heinlein doesn’t have to tell us that the English spoken on the moon is heavily influenced by Australian and Russian, he gives us a first person narrative devoid of articles and peppered with Russian borrowings and Australian slang. It’s great, but really it’s just scenery, everything else would be the same if he’d chosen to write the book in third with just the dialogue like that. It’s quite unusual to read something where the mode is absolutely integral to what the book is doing. In Womack’s *Random Acts of Senseless Violence*, the decaying grammar and vocabulary of the first person narrator, Lola, mirrors the disintegration of society around her, and we the reader slowly move from a near future with a near normal text to a complete understanding of sentences that would have been incomprehensible on page one, in a world that has also changed that much.

In Palmer’s Terra Ignota, after a page of (amazingly clever) permissions that locate us solidly in a future world with both censorship and trigger warnings (though we may not yet be aware we should take those trigger warnings very seriously) we meet not a normal Twenty-First century “1” or even “Chapter 1” but an Eighteenth Century style “Chapter the First: A Prayer to the Reader.” Then we are addressed directly:

> You will criticize me, reader, for writing in a style six hundred years removed from the events I describe, but you come to me for an explanation of those days of transformation which left your world the world it is, and since it was the philosophy of the Eighteenth Century, heavy with optimism and ambition, whose abrupt revival birthed the recent revolution, so it is only in the language of the Enlightenment, rich with opinion and sentiment, that those days can be described. [click to continue…]

{ 22 comments }