Animation on public walls in Buenos Aires.

Via Jenn Lena.

Posts by author:

Because Eric Rauchway‘s book on The Great Depression and New Deal makes inordinately heavy demands on the reader, is filled with hard-to-remember facts, and spends too much of its absurd length wistfully discussing fashions in men’s suits and hats of the period, I have been looking for a brief video to show in its place to undergrads in my social theory class. It’s good to finally have found it.

The first time I saw this, I honestly was waiting for a punchline at the end like, “Ponies – Free to Everyone”, or “Perpetual Motion Machines – Perfected”, or “Flying Cars – In a Range of Attractive Colors”. But it never comes, because it’s a real ad. Amazing.

Via Tina at Scatterplot, you must buy Wicked Anomie’s terrific Blind Reviewer Voodoo Doll. Designed for those moments when you need more than just a brisk letter to the journal editor explaining that your reviewer is unclear on a few points.

Via Tina at Scatterplot, you must buy Wicked Anomie’s terrific Blind Reviewer Voodoo Doll. Designed for those moments when you need more than just a brisk letter to the journal editor explaining that your reviewer is unclear on a few points.

This 9-inch doll (without hair) is lovingly crafted within the anomie studio and arrives finished and ready to be put to good use. This doll comes unstuffed, so that you can enjoy the cathartic act of shredding your own offending documents and stuffing them inside the doll. Finishing instructions and extra yarn included.

Proceeds go to fund designer’s trip to Annual Conference. Crooked Timber is not responsible for any stabbing pains you may experience in light of purchases encouraged by this post.

While at a conference in Germany over the weekend, I was initially quite chuffed by the greeting on my hotel-room TV:

But I quickly learned I am quite unable to compete on this front:

Somewhat more substantively, the conference, on norms and values, was attended by a bunch of interesting philosophers and political science types of a generally soft rat-choice disposition. As it happens, this week Aaron Swartz is writing about Jon Elster’s recent book, Explaining Social Behavior: More Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences. Aaron likes the book a lot. I haven’t read it, but now I’m curious to do so. Elster’s early work laid out an ambitious agenda for social science and its critical edge did a lot to kill off some styles of social explanation that were prevalent at the time. But then the prospects for achieving the more positive side of the research program seemed to recede in the face of efforts to achieve it, to the point where Elster became highly critical of work that might well have been inspired by Ulysses and the Sirens or Sour Grapes. The most recent book seems to be a comprehensive expression of late-Elsterian pessimism about the possibility of a general science of social explanation.

My colleague Lane Kenworthy is profiled this week at normblog. Lane’s blog, Consider the Evidence, is well worth your time.

Northwestern University has withdrawn its offer of an honorary degree to the Rev. Jeremiah Wright “in light of the controversy around” him. University Commencements in the U.S. are annual sites of ritual fighting over the appropriateness of commencement speakers and honorary degree recipients. Maybe this will be one of the highlights of the season. (Via Scatterplot.)

Just ten days or so ago Henry wrote that Chuck Tilly had won the SSRC’s Hirschman Prize, and linked to a classic paper of his. Tilly died this morning. He had been battling cancer for several years.

Just ten days or so ago Henry wrote that Chuck Tilly had won the SSRC’s Hirschman Prize, and linked to a classic paper of his. Tilly died this morning. He had been battling cancer for several years.

Tilly was a comparative and historical sociologist, an analyst of social movements, a social theorist, a political sociologist, a methodological innovator — none of these labels quite capture the scope of his work. I think of him as someone who was interested in the general problem of understanding social change, and he attacked it with tremendous, unflagging energy. Here is one of his own self-descriptions:

Among Tilly’s negative distinctions he prizes 1) never having held office in a professional association, 2) never having chaired a university department or served as a dean, 3) never having been an associate professor, 4) rejection every single time he has been screened as a prospective juror. He had also hoped never to publish a book with a subtitle, but subtitles somehow slipped into two of his co-authored books.

I saw him speak on several occasions and met him a few times, too. I particularly remember him giving the Mel Tumin lecture at Princeton, and a great chat I had with him in his office at Columbia. He was a small, wiry man who always seemed to be smiling and, like a true Weberian charismatic figure, he seemed able to transmit some of his own brio to you as he talked.

Humphrey Lyttelton has died. The Guardian has an obituary written by George Melly, who also happens to be dead.

I first came across Lyttelton not on Radio 4, but in Peter Winch’s The Idea of a Social Science and its Relation to Philosophy, of all places. He pops up there in an anecdote showing why some kinds of social practice are in principle not amenable to precise predictions derived from some (putative) social physics. Lyttelton was once asked if he knew where jazz was going, and replied “If I knew where jazz was going, I’d be there already.”

Here is a Stephen Colbert interview with Bill O’Reilly from last year. A friend drew my attention to an intriguing exchange they had. Eary in the interview O’Reilly gives Colbert some stick for the slient ‘t’ in his surname, saying “You’re French” and that “You used to be Stephen Colbert.” Colbert claims he’s even more Irish than O’Reilly. The conversation moves on, then at 5’45” this happens:

BO’R: Now, your middle name is “Tyrone.”

SC: It is.

BO’R: How could that possibly happen?

SC: Because I’m Irish, Bill. Have you ever been-

BO’R: You’re French.

SC: Have you ever been to Tyrone?

BO’R: There isn’t one Irishman …

SC: Have you ever been …

BO’R: … on earth named “Col-bear.”

SC: Have you ever – Colbert! Con Colbert of the Easter Rebellion of 1916.

BO’R: Oh, now you’re Colbert again!

SC: I thought you had researchers.

BO’R: WHO ARE YOU? Are you Colbert or Col-bear?

SC: Bill,…I’m whoever you want me to be.

And, indeed, Captain Con Colbert was a participant in the Easter Rising, and was executed by the British for his efforts. That seems like a very obscure thing for him to know off the top of his head. I suppose maybe Colbert has very good researchers (unlike O’Reilly), and they fed him this to bash O’Reilly with. But he does come from a large Irish family, so maybe he knew it himself. He also (again unlike O’Reilly) knows how to pronounce “Tyrone” properly.

Via Sally Satel, here’s a bit from a Freakonomics discussion. Stephen Dubner asked a bunch of people, “How much progress have psychology and psychiatry really made in the last century?” One of the respondents, Dan Ariely (a Professor of Management at MIT) cites some work about organ donation (emphasis added):

One of my favorite graphs in all of social science is the following plot from an inspiring paper by Eric Johnson and Daniel Goldstein. This graph shows the percentage of people, across different European countries, who are willing to donate their organs after they pass away. When people see this plot and try to speculate about the cause for the differences between the countries that donate a lot (in blue) and the countries that donate little (in orange) they usually come up with “big” reasons such as religion, culture, etc. But you will notice that pairs of similar countries have very different levels of organ donations.

For example, take the following pairs of countries: Denmark and Sweden; the Netherlands and Belgium; Austria and Germany; and (depending on your individual perspective) France and the U.K. These are countries that we usually think of as rather similar in terms of culture, religion, etc., yet their levels of organ donations are very different.

So, what could explain these differences? It turns out that it is the design of the form at the D.M.V. In countries where the form is set as “opt-in” (check this box if you want to participate in the organ donation program) people do not check the box and as a consequence they do not become a part of the program. In countries where the form is set as “opt-out” (check this box if you don’t want to participate in the organ donation program) people also do not check the box and are automatically enrolled in the program. In both cases large proportions of people simply adopt the default option.You might think that people do this because they don’t care — that the decision about donating their organs is so trivial that they can’t be bothered to lift up the pencil and check the box. But in fact the opposite is true. … The organ donation issue is just one example of the influence of rather “small” changes in the environment (opt-in vs. opt-out) on our decisions.

Johnson and Goldstein’s work on the role of default options in decision-making is good, but the figure above (especially with its y-axis labeled “Effective Consent Percentage”) is misleading as presented by Ariely. First he says, correctly, that the data show “the percentage of people, across different European countries, who are willing to donate their organs after they pass away.” But then he says, wrongly, that “similar countries have very different levels of organ donations.” The graph shows the number of people who say they are willing in principle to be donors, and the large difference that the default option to this question makes. The casual reader might think — as Ariely himself seems to — that the actual rate of organ procurement in those presumed-consent countries is vastly higher than that in informed-consent countries. But this is not the case at all. The figure shows is how many people sign up given the defaults (opt-in vs opt-out), and _not_ the rate of actual organ donors procured.

Here is a figure showing the organ procurement rate for various presumed- and informed-consent countries from the early 1990s to 2002 or so. Each green circle is the procurement rate for a particular country-year. (I want to focus on average differences between countries so I don’t show the time series itself. Click here for a figure showing the time trends.)

You can see that there are differences in the procurement rate between presumed- and informed-consent countries, and the highest-performing presumed-consent countries on average (Spain, Austria) score higher than the highest-performing informed consent countries. But the differences are not that big, and they are probably due mostly other features of the procurement system in the presumed consent countries. There is certainly not the huge disparity you might believe exists from a quick look at the post on the Freakonomics blog . (Incidentally, all of the countries shown here had their legal regime set as presumed- or informed-consent before the period covered by the data, so the often large within-country variability can’t be explained by the opt-in or opt-out defaults. Italy’s procurement rate, for instance, grew rapidly in the 1990s with no change in the law.)

In fact, as I’ve discussed recently in this post and argue in this paper, it is not at all clear that consent laws per se have any strong effect on the procurement rate (as distinct from their effect on people’s attitudes). Even if most people support organ donation, there are still large logistical hurdles to be overcome at the point of procurement. It is investment in the procurement infrastructure that really makes the difference to rates of organ donation, even if default options to opt-in or opt-out have large effects on people’s professed willingness to participate in the system.

_Update_: John Graves at the IQSS Blog makes the same error. As always, it is striking how easy it is for a mistake like this to propagate.

Like Henry, I bought the Old School Sesame Street collection for, uh, my kids. Yeah, totally for them. There’s all kinds of good stuff in there, including the God of the Classroom, Roosevelt Franklin. The improvised interactions with children who don’t always do what they are supposed to are also great. For instance, here is a great moment where Paul Simon sings an short version of “Me and Julio Down by the School Yard.” Slightly sour as always, Simon takes the song quite fast, as if he wants to just get it over with. He is immediately upstaged by the improvisations of the little girl sitting next to him. After he cuts her off, so he can start singing, she waits for her opening and then upstages him again. But by then even he is enjoying himself.

And as an added bonus, Here is Stevie Wonder playing “Superstition” live on Sesame Street. Beats the shit out of Barney, I’m telling you.

So that way, you can do something about this:

The European Commision has opened the door for mobile phones on planes, introducing measures to harmonize the technical and licensing requirements for mobiles services in the sky. This means that 90 percent of European air passengers can remain contactable during flights, according to the Commission. … As a result of the introduction of the measures by the Commission, local regulators will be able to hand out licenses to make services a reality. One regulatory decision for all of Europe was required for this new service to come into being, according to Viviane Reding, the European Union Telecommunications Commissioner. “In-flight mobile phone services can be a very interesting new service especially for those business travelers who need to be ready to communicate wherever they are,” she said in a statement.

As Kevin Drum remarked recently in connection with the possibility of acquiring the power to remain invisible, the question is not so much whether you would like to be able to do this, but whether you’d be happy if everyone else could do it, too. Looking forward, I wonder whether, in a decade or so, people who are irritated by endless yakking on a long flight will be a robust majority, or whether their disgust will seem more in line with Leon Kass and his intense disapproval of people who eat ice-cream in public.

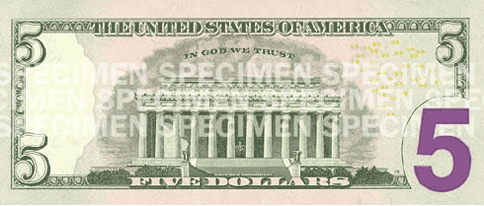

Via John Gruber comes news that the already somewhat odd augmenting of U.S. currency with larger typefaces and random bits of color has taken a horrible turn. Behold the new five dollar bill.

The new additions to this bill, apparently intended to increase legibility and accessibility, were made by my daughter, who is four. Or possibly by Harold and His Purple Crayon. Actually, as the folks at Hoefler & Frere-Jones point out, this monstrosity is in fact “the work of a 147-year-old government agency called the United States Bureau of Engraving and Printing. It employs 2,500 people, and has an annual budget of $525,000,000.”

Meanwhile in Britain, the design for their new line of coins was selected after an open competition and is the work of a 26 year-old designer who hadn’t tried his hand at coin design before.