From the category archives:

Academia

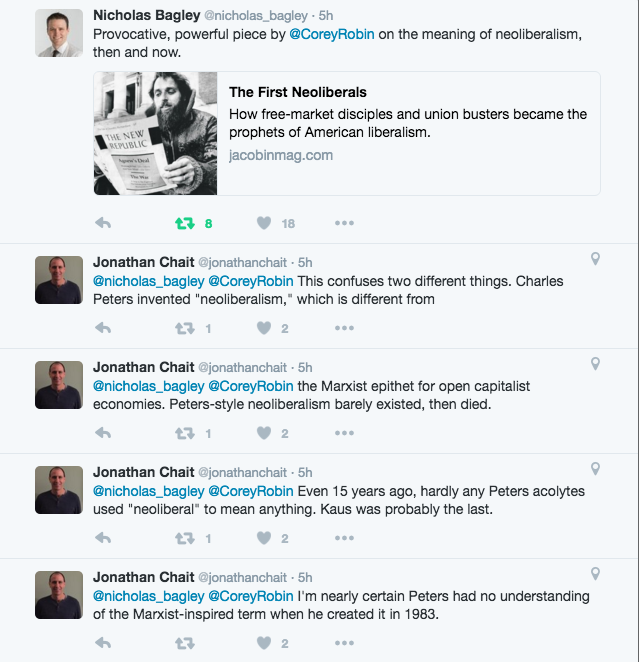

My post on neoliberalism is getting a fair amount of attention on social media. Jonathan Chait, whose original tweet prompted the post, responded to it with a series of four tweets:

The four tweets are even odder than the original tweet. [click to continue…]

Yesterday, New York Magazine’s Jonathan Chait tweeted this:

What if every use of “neoliberal” was replaced with, simply, “liberal”? Would any non-propagandistic meaning be lost?

— Jonathan Chait (@jonathanchait) April 26, 2016

It was an odd tweet.

On the one hand, Chait was probably just voicing his disgruntlement with an epithet that leftists and Sanders liberals often hurl against Clinton liberals like Chait.

On the other hand, there was a time, not so long ago, when journalists like Chait would have proudly owned the term neoliberal as an apt description of their beliefs. It was The New Republic, after all, the magazine where Chait made his name, that, along with The Washington Monthly, first provided neoliberalism with a home and a face.

Now, neoliberalism, of course, can mean a great many things, many of them associated with the right. But one of its meanings—arguably, in the United States, the most historically accurate—is the name that a small group of journalists, intellectuals, and politicians on the left gave to themselves in the late 1970s in order to register their distance from the traditional liberalism of the New Deal and the Great Society. The original neoliberals included, among others, Michael Kinsley, Charles Peters, James Fallows, Nicholas Lemann, Bill Bradley, Bruce Babbitt, Gary Hart, and Paul Tsongas. Sometimes called “Atari Democrats,” these were the men—and they were almost all men—who helped to remake American liberalism into neoliberalism, culminating in the election of Bill Clinton in 1992.

These were the men who made Jonathan Chait what he is today. Chait, after all, would recoil in horror at the policies and programs of mid-century liberals like Walter Reuther or John Kenneth Galbraith or even Arthur Schlesinger, who claimed that “class conflict is essential if freedom is to be preserved, because it is the only barrier against class domination.” We know this because he recoils in horror today so resolutely opposes the far more tepid versions of that liberalism that we see in the Sanders campaign.

It’s precisely the distance between that lost world of 20th century American labor liberalism and contemporary liberals like Chait that the phrase “neoliberalism” is meant, in part, to register. [click to continue…]

Last week, an announcement went out from The Nation that, while barely mentioned in the media-obsessed world of the Internet, echoed throughout my little corner of the Internet. John Palattella will be stepping down from his position as Literary Editor of The Nation in September, transitioning to a new role as an Editor at Large at the magazine.

For the last nine years, John has been my editor at The Nation. I wrote six pieces for him. That may not seem like a lot, but these were lengthy essays, some 42,000 words in total, several of them taking me almost a year to write. That’s partially a reflection on my dilatory writing habits, but it also tells you something about John’s willingness to invest in a writer and a piece.

John is not just an editor. Nor is he just an editor of one of the best literary reviews in the country. John is a writer’s editor. [click to continue…]

Again, it’s Krauthammer Day. Today is the unlucky thirteenth anniversary of the day when the prominent pundit announced:

Hans Blix had five months to find weapons. He found nothing. We’ve had five weeks. Come back to me in five months. If we haven’t found any, we will have a credibility problem.

As of today, we’ve had five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months and five months, and another month on top of that of Charles Krauthammer’s credibility problem. He’s still opining.

I have a piece up on the New Yorker blog, on the same theme as Damien Hirst’s 1991 shark-in-formaldehyde artwork[1], as applied to big banks and their remarkable inability to write contingency plans for what they would do if they needed to declare bankruptcy, despite being point blank ordered by the regulators to do so.

[click to continue…]

Apologies in advance for all the formatting foul-ups. My usual formatting guru, John Holbo, is off somewhere arguing about the Commerce Clause…

1.

At Vox, Dylan Matthews offers a sharp analysis of last night’s debate, which I didn’t watch or listen to. His verdict is that the three big losers of the night were Hillary Clinton, the New Democrats, and liberal technocrats. (The two winners were Bernie Sanders and Fight for $15 movement.) As Matthews writes:

But just going through the issues at tonight’s debate, it’s striking to imagine a DLCer from the ’90s watching and wondering what his party had come to. Sanders was asked not if he was sufficiently tough on crime, but if his plans to let millions of convicted criminals out of prison would actually free as many felons as promised. Clinton was criticized not for being insufficiently pro-Israel, but for being insufficiently willing to assail the killing of Palestinian civilians. Twenty years after Clinton named former Goldman Sachs chief Robert Rubin as his Treasury secretary, so much as consorting with Goldman Sachs had become toxic.

Though I’m obviously pleased if Sanders beat Clinton in the debate, it’s the other two victories that are most important to me. For those of us who are Sanders supporters, the issue has never really been Hillary Clinton but always the politics that she stands for. Even if Sanders ultimately loses the nomination, the fact that this may be the last one or two election cycles in which Clinton-style politics stands a chance: that for us is the real point of this whole thing.

I‘m always uncertain whether Clinton supporters have a comparable view. While there are some, like Jonathan Chait or Paul Starr, for whom that kind of politics is substantively attractive, and who will genuinely mourn its disappearance, most of Clinton’s supporters seem to be more in synch with Sanders’s politics. They say they like Bernie and agree with his politics; it’s just not realistic, they say, to think that the American electorate will support that.

Which makes these liberals’ attraction to Clinton all the more puzzling. If it’s all pure pragmatism for you—despite your personal support for Bernie’s positions, you think only her style of politics can win in the United States—what are you going to do, the next election cycle, when there’s no one, certainly no one of her talent or skills and level of organizational support, who’s able to articulate that kind of politics? [click to continue…]

We talk a lot on this blog about pedagogy and other issues related to classroom instruction in the academy. I don’t often participate in those discussions, though I read them avidly, with great interest and appreciation. I suppose it’s because the issues raised there sometimes seem a bit removed from what I encounter at CUNY.  But I posted this post last night on my blog, and spurred on by an appreciative tweet from Henry, I thought I’d share it here. Teaching’s not always like this at CUNY, but it often is. I remember my first semester at Brooklyn College, teaching a nighttime seminar on liberalism and constitutional law. I’ll never forget, about an hour after the class had ended, I walked by the classroom on my way home and there were three students—one from Nigeria, one from Eastern Europe, and one who was African American—still arguing over some passage from On Liberty. It sounds like something out of a movie, and the truth is, it often feels that way. More than 15 years later, I still sometimes fantasize that I’m teaching the next generation of the New York Intellectuals. Only instead of them being the children of East European Jews, they’re from the Caribbean, West Africa, Palestine, Yemen, Turkmenistan. They’re black, they’re Latina, they’re Muslim, they’re working class, they’re Orthodox Jewish, and they come from everywhere.

* * * * *Â

I’m not one of those professors who says, “I love my students,” but…I love my students. [click to continue…]

When some things have holes in them, it’s a sign of decay, like a beam with termites. But some things are meant to have holes, like Swiss cheese. I agree with John’s view on “holes and gaps”, but as always, I tend to assign agency to the political system more than to the financial sector. Nearly all of those holes were intended to be there, and it was intended that the financial system used them. The process whereby the behaviour involved is redefined from acceptable deviancy to unacceptable is very interesting, like the last chapters of a John le Carre novel by way of Foucault. A few thoughts below, ranging in geopolitical scope from “vast” to “cosmic”, in a comment which grew into an alternative monetary history of the second half of the twentieth century.

Leiter has an interesting post on why undergraduate women give up on philosophy. A senior female philosopher diagnosed the problem, and started with the following comment:

My assessment of the undergrad women in philosophy thing: undergrad women get sick of being talked over and strawmanned by their peers in and out of the classroom, and get sick of classes where the male students endlessly hold forth about their own thoughts.

Leiter adds:

I will say that over two decades of teaching, it has seemed to me that the students who speak out of proportion to what they have to say are overwhelmingly male.

My experience is exactly the same as Leiter’s. And I’ve heard from countless female students that they just got tired of being ignored, both by prof and male students, and also tired of trying to get a word in among the ramblings of boys who think that they are really smart. Even in classes taught by women. And in classes, I’m embarrassed to say, taught by me. To make things worse I think that such behavior can be a very good strategy for learning – it gets you the professor’s attention, and the professor will correct you or argue with you, even if they are extremely irritated, and you can learn a lot from that.

Leiter goes on that “Maintaining control of the classroom, and creating a welcoming environment for all student contributions, can probably go some distance to rectifying this–but that, of course, supposes levels of pedagogical talent and sensitivity that many philosophy faculty probably lack.”

I almost completely agree with this, but would substitute the word ‘skill’ for ‘talent’. I’d say that if you really feel you lack the talent to manage the classroom in this way, so do not think it is worth investing in learning how to do it, I advise that you avoid teaching in mixed male/female classrooms, or find a job that doesn’t involve teaching. But I think most of us have the talent, we just lack the skill because as a profession, at least at R1s, we are spectacularly complacent about developing our pedagogical talents into skills. We focus considerable effort on developing our talent as researchers, consuming the research of others, discussing their research, our research, and other people’s research in a community of learner/researchers, putting our research out for comments from friends and, ultimately, for review and publication. We ought to become pretty good at it. But as a recent paper by David Conception and colleagues shows, we receive hardly any training in instruction, and once we become teachers we might try very hard, but we invest very little in the kinds of processes that would enable us to learn from experts, as opposed to improving through trial-and-error. It is like trying to become a good violin player without anyone ever listening to you, and without ever listening to anyone who plays it well. Possible, I suppose, but hardly a recipe for success.

So, from my own trial and error (combined with some watching of experts, and employing coaches to observe me) here are some things that I have learned how to do which seem to me to make the classroom one in which women participate at a similar rate to men and seem to reduce the problem of particular male students dominating the room.

Reading Samuel Freeman’s review of conservative philosopher Roger Scruton in the latest NYRB, I had a mini-realization about my own work on conservatism, which features Scruton a fair amount.

In the mid-1970s, conservatism, which had previously been declared dead as an intellectual and political force, started to gain some political life (its intellectual rejuvenation had begun long before). As it did, conservatism began to have an impact on liberalism. Politically, you could see that influence in the slow, then sudden, retreat from traditional New Deal objectives, culminating in the election of Bill Clinton. What that meant was a massive turnaround on economic issues (deregulation, indifference to unions, galloping inequality) and a softer turnaround on so-called social or moral issues. While mainstream Democrats today are identified as staunch liberals on issues like abortion and gay rights, the truth of the matter is that in the early 1990s, they beat a retreat on that front (not only on abortion but also, after an initial embrace of gays and lesbians, on gay rights as well).

Among liberal academics, the impact of conservatism was equally strong. Not only in the obvious sense that conservatism became an object of increasing scholarly interest, particularly among historians. But also in a deeper sense, as the categories of traditional conservative concern, like religion, came to assume a greater role in scholarly inquiry.

The impact was especially dramatic in the world of liberal political theory. [click to continue…]

Last week I met with a group of ten interns at a magazine. The magazine runs periodic seminars where interns get to meet with a journalist, writer, intellectual, academic of their choosing. We talked about politics, writing, and so on. But in the course of our conversation, one startling social fact became plain. Although all of these young men and women had some combination of writerly dreams, none of them—not one—had any plan for, even an ambition of, a career. Not just in the economic sense but in the existential sense of a lifelong vocation or pursuit that might find some practical expression or social validation in the form of paid work. Not because they didn’t want a career but because there was no career to be wanted. And not just in journalism but in a great many industries.

The future was so uncertain, they said, the economy so broken, there simply was no point in devising a plan, much less trying to execute it. The best one could do, one of them said, was to take whatever came your way, without looking more than six months ahead of you.

They even dreamed of the Chilean example, where an activist a few years ago burned what he claimed was $500 million in student debt. Sadly, they pointed out, that option wasn’t available in the US, where all of the debt is up in the cloud. (How strange, I thought to myself: once upon a time, utopian philosophers had their heads in the clouds; that was where they found a better world. Now it is the most dreary and repressive forces of society—drones, surveillance cameras, debt collectors—that take up residence there, ruling us from their underworld in the sky.) [click to continue…]