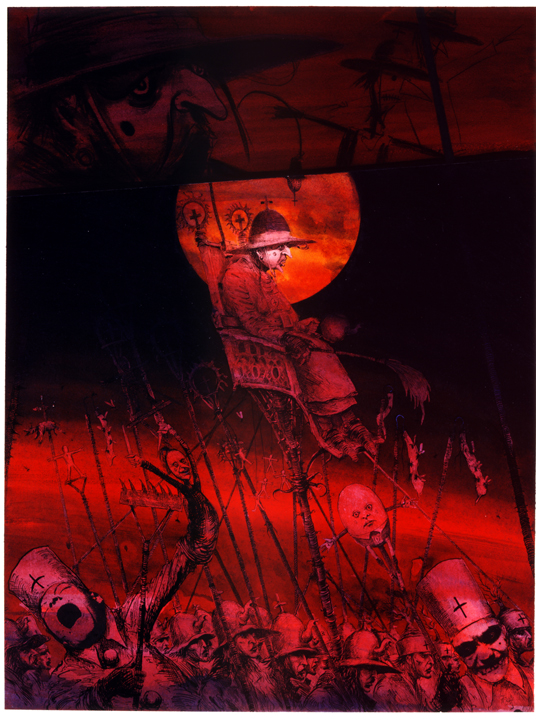

A new collection of Ian Miller‘s art is out today. When I was in my early twenties, I was mildly obsessed by Miller’s graphic novel collaboration with M. John Harrison, The Luck in the Head, to the point that a few years ago, when I could finally afford to, I bought a couple of the originals, including the ‘Procession of the Mammy’ shown above (reproduction isn’t wonderful; it’s far sharper and not nearly as drenched with red in real life).

I thought about this graphic novel, and the Harrison short story it built on a lot last year, when Margaret Thatcher died. Neil Gaiman describes in his introduction to Harrison’s work how:

For me, the first experience of reading Viriconium Nights and In Viriconium was a revelation. I was a young man when I first encountered them, half a lifetime ago, and I remember the first experience of Harrison’s prose, as clear as mountain-water and as cold. The stories tangle in my head with the time that I first read them – the Thatcher Years in England seem already to be retreating into myth. They were larger-than-life times when we were living them, and there’s more than a tang of the London I remember informing the city in these tales, and something of the decaying brassiness of Thatcher herself in the rotting malevolence of Mammy Vooley (indeed, when Harrison retold the story of “The Luck in the Head” in graphic novel form, illustrated by Ian Miller, Mammy Vooley was explicitly drawn as an avatar of Margaret Thatcher).

He doesn’t mention (but then it’s an aside) how Harrison and Miller’s collaboration captures the contrast between Thatcher’s role as emblem and her frailty as a human being. In the picture, she’s already become a kind of ritual object, carted around to no particular purpose beyond display. Like the teapots that are the helmets of her supporters, she’s been superannuated and put to new uses that are both ludicrous and sinister. Another panel shows her after the procession, without her wig, shaven-headed, exhausted and empty, pushed along in a bath-chair by a lackey wearing a fish-head mask (a reference both to Miller’s art – he likes to draw fish – and to an incident in Harrison’s short novel _In Viriconium_). Miller and Harrison depict Thatcherism not as the revolution it believed itself to be, but as an aftermath where the symbols have been emptied of all meaning. Put another way, the senescent Thatcher depicted by Miller and Harrison’s Mammy Vooley represents less a foretelling of Thatcher’s own decline, than the decay of the movement that she represented (a decay which was already present in its moment of full flowering).