Ta-Nehisi Coates really likes Moby Dick, apparently the first paragraph in particular.

But not everyone feels the same. Reminds me of that great scene in Bone, vol. 5, when they are being attacked by the Stupid Rat Creatures … [click to continue…]

From the category archives:

Ta-Nehisi Coates really likes Moby Dick, apparently the first paragraph in particular.

But not everyone feels the same. Reminds me of that great scene in Bone, vol. 5, when they are being attacked by the Stupid Rat Creatures … [click to continue…]

One of the snags with really great artists is that they feed the illusion that the past is comprehensible: reading Jane Austen or listening to Beethoven, I can register a different set of manners and assumptions without feeling that there’s something utterly alien going on. (Critics generally settle for the adjective “timeless”.) Watching Charlie Chaplin, on the other hand, I’m always conscious of the chasm between then and now, how different modern times are from anything that went before. I don’t think this sense of strangeness has much to do with the question of whether we find him funny or not (the idea that Chaplin isn’t funny has fallen out of fashion in recent years, and I think it’s generally recognised that some of the time he’s very funny). But leaving aside Chaplin’s astoundingly deft comic shtick, the whole emotional world of the films seems primitive and impenetrable; I have trouble swallowing the Little Tramp himself as a sympathetic character, though the audiences a century back don’t seem to have felt any ambivalence.

I’m leading up to a proposition: that Chaplin has slipped out of our grasp. [click to continue…]

I had a simply heart-breaking experience, reading Sunnyside. (Strictly, I listened to it on Audiobook. So the following page numbers, courtesy of Amazon search-inside, do not correspond to my original ‘reading’ experience.)

Leland “Lee Duncan” Wheeler is about to audition.

The house lights went up momentarily, for the judges to introduce themselves. Each in turn stood up, announced his or her associations, then sat. Mrs. Franklin Geary, head of the Liberty Loan Committee, Christopher Sims of the Institute for Speech Benevolence … (246)

Then, on p. 256.

“We didn’t understand half of what he was doing. Mr. Sims, did you understand what he was doing?”

“I liked the kick to the face.”

Mrs. Geary frowned. “I thought he was swimming.”

You get it? Sims? Of the ISB? And the kick to the face seals the deal. I was so proud I spotted it. I emailed Sims to report my discovery of this wonderful Easter Egg and … he’d … already noticed it … himself. Way to let the air out of my little Easter Egg.

But now you know. That’s something they can put on my tombstone, I guess. [click to continue…]

On first reading, Sunnyside seems to be a picaresque with a sting in the tail. In the best spirit of Chaplin’s films, this rambling story of World War I and the movies uses slapstick and pathos to wring out tears of laughter and sadness. Many readers set it down, bemused, scratching their heads, wondering what, if anything, it was all about. Some reviewers said it was an ambitious failure. Sunnyside is a book you need to live with for a while as it unwraps itself. Or not. Like the best comedy, it’s a response, though not an answer, to the despair of the human condition. And it’s very, very funny.

On first reading, Sunnyside seems to be a picaresque with a sting in the tail. In the best spirit of Chaplin’s films, this rambling story of World War I and the movies uses slapstick and pathos to wring out tears of laughter and sadness. Many readers set it down, bemused, scratching their heads, wondering what, if anything, it was all about. Some reviewers said it was an ambitious failure. Sunnyside is a book you need to live with for a while as it unwraps itself. Or not. Like the best comedy, it’s a response, though not an answer, to the despair of the human condition. And it’s very, very funny.

What does it mean to ‘get’ a book, or at least to think you have? It’s something that happens in a reader’s mind when the characters, story, feelings and ideas of a novel unite into something greater than their sum, becoming a complete world of their own, a world that teaches true things about the world we live in. A good book that sits uncomfortably in its own era resists understanding just as it teaches you how to read it. Sunnyside is the sort of book you think about for a long time after reading, and will probably come back to again. [click to continue…]

Yep. Green Lantern and Philosophy: No Evil Shall Escape this Book [amazon] is a book. I can’t believe there is no mention of Matthew Yglesias. Not even a chapter on foreign policy.

Let’s be serious. Example: the entry on ‘serious’ from the Super Dictionary. A reference work that, of late, is slouching toward canonicity.

I think Green Lantern has just proposed Jonah Goldberg’s book for the JLA Watchtower reading group. Hence the wooden floor. [click to continue…]

The Importance of Story in Sunnyside

In a narrative bursting with stories, fictions, verbal sleight-of-hand, deliberate lies and other debateable information, Glen David Gold’s Sunnyside has a very strained relationship with its own truth and reality. There are so many examples, large moments and set plays which explore this – and which I will investigate later – but to me the crux of Sunnyside is expressed in a small running gag: that of Chaplin himself entering a Chaplin lookalike competition, and only coming in fourth.

It’s a familiar joke –an urban legend that has also been attributed to Elvis Presley, amongst others – and one that perfectly encapsulates the problem that so many of the characters in the novel face: they don’t really know who they are; and more importantly, they don’t know how they portray themselves to others. They are stitched together from uncertain memories, false information and a diet of lies: whether that be from parents, the government or from the cinema. All they have are their stories and, just as in the result of Chaplin’s lookalike contest, nothing is to be taken for granted.

Gold unnerves us with this lack of certainty as early as the preliminary pages of the book. The quotation that greets us – I was loved, Mary Pickford – is immediately subverted by her being cast in the starring line-up as “an enemy”. These are clues that point to the myriad delusions that befall America, including the umpteen sightings of Chaplin on the same day, seemingly a whole nation experiencing something impossible, and yet still believing it. As Gold himself puts it: “Such is the nature of the inexplicable that, as long as it does not involve money, it can be ignored.” [click to continue…]

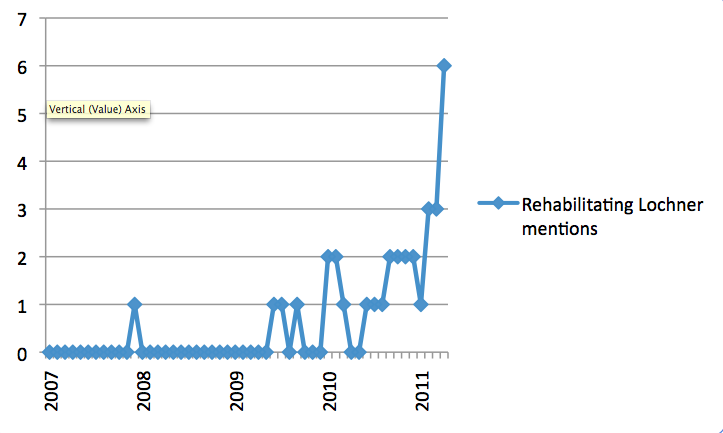

David Bernstein, who clearly worries that he didn’t “promote his last book quite enough”:https://crookedtimber.org/2003/10/31/dept-of-fair-and-balanced/, is offering “various special deals on the new one”:http://volokh.com/2011/05/19/rehabilitating-lochner-publication-date-special/ over at the _Volokh Conspiracy._ The worrying thing is not that this is the “34th post”:http://volokh.com/?s=%22rehabilitating+lochner%22 that he has written touting the book in some way. It’s the rate at which the frequency of mentions appears to be increasing. For your collective edification, I have graphed the number of mentions of the book by month between 2007 and the end of April 2011.

As is immediately apparent, the number of mentions is now increasing exponentially. Should this frightening trend continue, reliable back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that by September 2011, the publishing output of the _Volokh Conspiracy_ will consist entirely of book plugs for David Bernstein.

Would that it ended there. Some thirty-four months after that (numerologists take note of this significant coincidence), the entire Internet will be made up of blogposts lauding the virtues of _Rehabilitating Lochner_ (and offering t-shirts to every lucky fifth buyer). Not all that long after that, these posts will start straining the theoretical information-storage capacity of the planet, and, sometime within my expected lifetime, that of the galaxy. Even Charlie Stross couldn’t have predicted this one.

Pedants, potato-counters and other such folk will no doubt point to the dangers of making extrapolations from “apparent hyperbolic growth processes”:http://agrumer.livejournal.com/414194.html. But if anything, I suspect my predicted growth-curve is a gross under-estimation. After all, the book hasn’t _even been officially released yet._ One can only imagine how much further the process will accelerate once there are book tours, right-wing radio talkshow appearances and the like to chronicle exhaustively in repeated updates. And _please!_ don’t anyone tell tell him about Twitter.

Despite having recently co-edited a book on Moretti’s work [free! free download, or buy the paper!], I haven’t yet commented on his Hamlet paper, which Kieran brought to our collective attention. Because I only just now got around to reading it, and sometimes it’s good practice to hold off until you do that, even though this is the internet and all.

First things first: if you can’t access the LRB version, there’s a free, longer version available from Moretti’s own lab.

Right, the whole thing reminds me of that memorable scene in the play in which Hamlet puts on a PPT presentation, representing social networks in The Marriage of Gonzago nudge nudge wink wink. (Apparently he’s been working on this stuff at school for years.) And Ophelia doesn’t really get it and Hamlet helpfully explains: “Marry, this is miching mallecho; it means mischief.”

But seriously, folks. I like the paper, and I don’t like it. On the one hand, I wholeheartedly endorse this bit. Or at least I would very much like to be able to. [click to continue…]

The current issue of New Left Review has an article by Franco Moretti applying a bit of network analysis to the interactions within some pieces of literature. Here is the interaction network in Hamlet, with a tie being defined by whether the characters speak to one another. (Notice that this means that, e.g., Rosencrantz and Guildenstern do not have a tie, even though they’re in the same scenes.)

The Hamlet network

And here is Hamlet without Hamlet:

Hamlet without Hamlet

I think we can safely say that he is a key figure in the network. Though the Prince may be less crucial than he thinks, as Horatio seems to be pretty well positioned, too. Lots more in the article itself.

I’m thinking about doing another book, which would be a reply to Henry Hazlitt’s Economics in One Lesson a tract published in 1946, and available online, but still in the Amazon top 1000. It’s largely (as Hazlitt himself says) a rehash of Bastiat.

I’ll try to put up a prospectus soon, but I thought I’d start with something simpler, a response to Leonard Read’s I, Pencil.

Update I’m getting a lot out of the comments, and updating the piece in response.

This essay is a description of the incredibly complex “family tree” of a simple pencil, making the point that the production of a pencil draws on the work of millions of people, not one of whom could actually make a pencil from scratch, and most of whom don’t know or care that their work contributes to the production of pencils. So far, so good. Read goes on to say that

There is a fact still more astounding: the absence of a master mind, of anyone dictating or forcibly directing these countless actions which bring me into being. No trace of such a person can be found. Instead, we find the Invisible Hand at work.

Hold on a moment!

A piece I wrote on China Miéville’s _The City and the City._ has “come out”:http://bostonreview.net/BR36.2/henry_farrell_china_mieville.php in the _Boston Review_. The nub of my argument:

bq. Miéville brings these quotidian practices into stark perspective. He uses slips of perception and movement back and forth between cities to highlight the contingency of many of the social aspects of the real world. The City & the City draws no hard distinction between the world of fantasy and our own. Instead, Miéville seems to suggest, the real world is composed of consensual fantasies of varying degrees of power. The slippage isn’t between the real world and the fantastic, but between different, equally valid, versions of the real. As the title makes explicit, neither city has ontological priority over the other—Besźel is not a simple reflection of Ul Qoma, or vice versa.

I mentioned Farah Mendlesohn’s “Rhetorics of Fantasy”:http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0819568686/ref=as_li_ss_tl?ie=UTF8&tag=henryfarrell-20&linkCode=as2&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=0819568686 in the piece, but I wasn’t able to make clear how great a debt I owe to it (since Farah is an occasional CT reader, I hope this post can serve as both thanks and public acknowledgment). _Rhetorics of Fantasy_ allowed me to figure out what I thought about the book (some have “suggested”:http://vectoreditors.wordpress.com/2009/05/22/mr-h-mr-h-discuss-the-city-the-city/ that it’s indeed one of the texts behind TCATC. Its argument – brutally simplified – is that the different modes in which fantasy authors represent the relationship between the world they have created and the real world has important rhetorical consequences. Thinking about fantasy in this way highlights just what is most interesting about TCTATC – that it is a fantasy of superimposed worlds, none of which is entirely fantastic (the genuinely fantastic elements of the book are extremely limited, and are a kind of macguffin), and each of which is just as rooted (or unrooted) in reality as the other. This allows Miéville to make the familiar strange – to treat something (or somethings) that closely resembles real life as if it was fantastical in the same way that your imagined-world-of-choice is fantastical. It is a very interesting shift in perception, and one which I do not think I would have been able to decode, at least to my own satisfaction, had I not read Farah’s book.

I got an email the other day, trying to set up an interview about Zombie Economics: How Dead Ideas Still Walk Among Us. Shortly afterwards there was a cancellation – they actually wanted the author of Zombie Economics: A Guide to Personal Finance, due to be released in May.

I’m well aware that there’s no copyright in book titles (Zombie Econ was originally going to be called “Dead Ideas from New Economists, and back in the 90s I wrote one which the publisher insisted on calling Great Expectations), but I can’t help wondering about the implications for sales. At least for the moment they don’t look too bad. According to Amazon, 12 per cent of people who viewed the doppelganger ultimately bought my book, while the proportion going the other way is zero (although some zombie fans go for Chris Harman’s Zombie Capitalism). But I imagine that’s the result of bad search results among people looking for mine, rather than a spillover from those looking for the doppelganger. If so, I imagine the flow will reverse when the new one is released.

Are there other interesting examples of book title recycling, or interesting ideas for new takes on classic titles?

I’ve got no time for a proper review, so this post is just a mention of Sarah Bakewell’s How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer [UK Link]. The academic in me was initially put-off by the self-helpy presentation of the book. Because of this, I imagined that it would be (a) irritating and (b) unscholarly. It is only unscholarly in the good sense that it does not come across as a work of dry academic research. And Bakewell isn’t irritating at all: her writing is fluid, witty and unpretentious. The book provides a compelling psychological portrait of Montaigne, contains plenty of interesting background on the wars of religion, and nudges the reader towards the Montaignian attitude of sceptical curiosity about self, others and the world. I enjoyed it tremendously (got through the 300+ pages in a few days) and am now rooting through the real thing, the Essays. Highly recommended.

They close tomorrow. I’m not eligible to vote, but if I was, I’d be nominating the following.

* Felix Gilman – The Half-Made World. See here for my thoughts, and here for Cosma Shalizi’s.

* Ian McDonald – The Dervish House. Very good and interesting near-future book on Turkey – blending together historical conspiracy, complexity theory, theories of religious experience and politics. It somehow works. “True wisdom leaks from the joins between disciplines.”

* China Mieville – Kraken. Not his most intellectually challenging book, and a little bit baggy, but enormous fun.

I’d also recommend Francis Spufford’s Red Plenty (which has surely _already_ won the Hugo in the alternate reality that spun off when _Gravity’s Rainbow_ won the award in 1973 (ok – it was the Nebula – but Artistic Licence!)), but I would prefer to wait on that recommendation until its US publication (sometime this year, I think). I also enjoyed Hannu Rajaniemi’s _The Quantum Thief_ (which also gets published in the US this year), but not as much as many others – the intellectual pyrotechnics are dazzling, but it’s still a fairly straightforward caper novel underneath it all. Feel free to add others, agree/disagree etc in comments.

The great “what will we do when the machines take over” debate continues, but surprisingly little attention has been paid to the arguments of licensed speculative economists science fiction writers, who have been engaged in this debate for some decades at least. The Bertram/Cohen “thesis”:https://crookedtimber.org/2011/03/07/oh-noes-were-being-replaced-by-machines/ receives considerable support from Iain Banks’ repeated modeling exercises with slight parameter variations, which find that the advent of true artificial intelligence will free human beings to spend their time playing complicated games, throwing parties, engaged in various forms of cultural activity (more or less refined), and having lots and lots of highly varied sex. With respect to the last, it must be acknowledged that extensively tweaked physiologies and easy gender switching are important confounding factors.

But it isn’t the only such intellectual exercise out there. Walter Jon William’s Green Leopard Hypothesis (update: downloadable in various formats here – thanks to James Haughton in comments) suggests, along the lines of the Cowen/DeLong/Krugman argument, that a technological fix for material deprivation will lead to widespread inequality and indeed tyranny, unless there be root and branch reform to political economy. But perhaps the most ingenious formulation is the oldest – Frederik Pohl’s Midas Plague Equilibrium under which robots produce consumer goods so cheaply that they flood society, and lead the government to introduce consumption quotas, under which the proles are obliged to consume extravagant amounts so as to use the goods up (the technocrats fear that any effort to tinker to the system will risk reverting to the old order of generalized scarcity). This is a world of conspicuous non-consumption in which the more elevated one’s social position the less possessions one is obliged to have. Crisis is averted when the hero realizes that robots can be adjusted so that they want to consume too, hence easing the burden. One could base an entire political economy seminar around Pohl’s satirical stories of the 1950’s and 1960’s – he was (and indeed arguably still is, since he is still alive and active ) the J.K. Galbraith of the pulps. If, that is, J.K. Galbraith had been a Trotskyist. I’m sure that there are other sfnal takes on this topic that I’m unaware of – nominations?