In the recent TLS I have an essay on Benn Steil’s new book on Bretton Woods. Unlike some notices, mine is critical. You can read mine here. If you’re interested in the theory, put forward in Steil’s book, that Harry Dexter White caused US intervention in World War II, read below the fold. If you’re more interested in the late Baroness Thatcher, please carry on down to the other posts for today.

From the category archives:

Economics/Finance

My review of Mark Blyth’s forthcoming book, _Austerity: A Dangerous Idea_ can be “found here”:http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/march_april_2013/on_political_books/slaves_of_defunct_economists043306.php. After I wrote the review, Dani Rodrik “published a piece”:http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/ideas-over-interests arguing that economists needed to pay less attention to interests, and more to ideas:

bq. Interests are not fixed or predetermined. They are themselves shaped by ideas – beliefs about who we are, what we are trying to achieve, and how the world works. Our perceptions of self-interest are always filtered through the lens of ideas. … So, where do those ideas come from? Policymakers, like all of us, are slaves to fashion. Their perspectives on what is feasible and desirable are shaped by the zeitgeist, the “ideas in the air.” This means that economists and other thought leaders can exert much influence – for good or ill. John Maynard Keynes once famously said that “even the most practical man of affairs is usually in the thrall of the ideas of some long-dead economist.” He probably didn’t put it nearly strongly enough. The ideas that have produced, for example, the unbridled liberalization and financial excess of the last few decades have emanated from economists who are (for the most part) very much alive. … Economists love theories that place organized special interests at the root of all political evil. In the real world, they cannot wriggle so easily out of responsibility for the bad ideas that they have so often spawned.

Blyth thinks very similarly about how ideas dominate interests, and how we need to take account of this studying the economy. As I summarize his take (building not only on the austerity book, but his previous work too):

Blyth cares about bad ideas because they have profound consequences. We do not live in the tidy, ordered universe depicted by economists’ models. Instead, our world is crazy and chaotic. We try to control this world through imposing our economic ideas on it, and sometimes can indeed create self-fulfilling prophecies that work for a while. For a couple of decades, it looked as though markets really were efficient, in the way that economists claimed they were. As long as everyone believed in the underlying idea of underlying markets, and believed that everyone else believed in this idea too, they could sustain the fiction, and ignore inconvenient anomalies. However, sooner or later (and more likely sooner than later), these anomalies explode, generating chaos until a new set of ideas emerges, creating another short-lived island of stability.

This means that ideas are fundamentally important. The world does not come with an instruction sheet, but ideas can make it seem as if it does. They tell you which things to care about, and which to ignore; which policies to implement, and which to ridicule. This was true before the economic crisis. Everyone from the center left to the center right believed that weakly regulated markets worked as advertised, right up to the moment when they didn’t. It is equally true in the aftermath, as boosters of neoliberalism have moved with remarkable alacrity from one set of bad ideas to another.

In yesterday’s elections in Italy, ‘voters defied a failing policy and a clapped-out political establishment‘, resulting in an indecisive outcome. Here is more evidence in the Eurozone of what the late Peter Mair called the conflict between ‘responsible’ and ‘responsive’ politics. The centre-left ‘responsible’ party of Pier Luigi Bersani won most votes, just about. But the über-‘responsible’ Mario Monti, the technocratic prime minister and Bersani’s most likely coalition partner, gained only half the support he had hoped for. Quelle surprise, one may be forgiven for thinking, since the mix of ‘austerity’-driven tax increases with no real structural reform, and with none of the stimulus that would enable reform to work, has proven highly unpopular with voters.

Once again, it seems to me, we see that it really is a mistake to leave the politics out of politics. I have some thoughts about why this is a bad idea in a recent talk (audio and slides here).

In his (relatively) new gig as business and economics correspondent at Slate, Matt Yglesias is really churning out lots of material. Often, it’s useful and insightful, but, inevitably quality control is imperfect. Arguably, there’s still a net benefit from the increase in output, provided readers apply their own filters. Nevertheless, I got a bit miffed by this post, which makes a mess of a topic, I’ve covered quite a few times, namely the question of whether US middle class living standards are declining as regards services like higher education.

As I’ve pointed out, the number of places in most Ivy League colleges has barely changed since the 1950s, and many top state universities have been static or contracting since the 1970s. In addition, the class bias in admissions has increased. College graduation rates have increased modestly since the 1970s, but an increasing proportion of post-school education is at lower-tier state universities as well community colleges offering only associate degrees.[1]

(Added in response to comments): Given static numbers at the top institutions, increasing populations, and a reduced share of admissions going to the middle class, education at the kinds of colleges usually discussed in this context (the top private and state universities) is an example where the middle class (roughly, the middle three quintiles) are getting less than they did 40 years ago. They’ve substituted cheaper second-tier and third-tier institutions where tuition, while rising fast, is much lower than at the Ivies, top state unis etc. But the chance of getting into the upper middle class (top quintile) with a degree from these schools is correspondingly lower. So, education as a route out of the middle class and into the top quintile is less accessible than forty years ago – this is leading to a reduction in already limited social mobility.

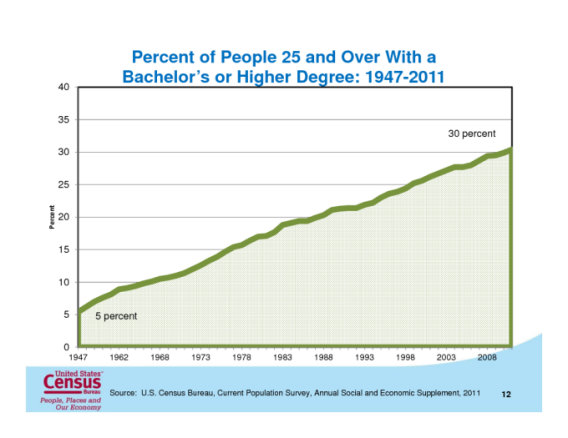

Yglesias says “Colleges charge much higher prices today than they did 40 years ago but many more people have college degrees” and backs this up with the following graph

What’s wrong with this picture?

[click to continue…]

If there were still magazine stands, I’d be all over them today. Three pieces of mine have (coincidentally) come out on in the last day or so, in fairly disparate publications

* In Aeon (a new British “digital magazine of ideas and culture, publishing an original essay every weekday”), I have a followup to my first essay there, which argued the case for a Keynesian utopia, with a drastic reduction in market working hours. In my follow-up, I look at the environmental sustainability of the idea. The tagline for the essay “For the first time in history we could end poverty while protecting the global environment. But do we have the will? ”

* Continuing on the utopian theme, Jacobin magazine has published The Light on the Hill, a reply to Seth Ackerman’s piece on market socialism, which has already been debated a bit here at CT

* And, at The National Interest, a piece with the self-explanatory title, Will Banks Finally Be Brought to Heel?

While I’m plugging my own work, I thought some readers might be interested in this paper on financial liberalisation and asset bubbles, written in the leadup to the global financial crisis. There’s not much I would change now, and it’s still a pretty good summary of how I think about the financial bubble that created the crisis. The linked working paper version is from 2004, and it eventually appeared in the Journal of Economic Issues, the main journal of the institutionalists who carry on the tradition started by Veblen and Commons in early C20. Not surprisingly, given this obscure outlet, it hasn’t had a lot of attention.

Summer[1] is the best time for reruns. A tweet from Kieran commenting to Matt Yglesias on the work of the late James Buchanan points to this 2003 post, which is itself a rerun of an article published back in the early 1990s. For added nostalgia value, it links to CT, before I joined. Thanks to Twitter, everything has a DD-style “Shorter” version now, and Kieran does a nice job “Buchanan allowed Economists to have a Marxist-Leninist theory of the capitalist state”.

The article was originally published in an Australian libertarian magazine, and annoyed plenty of readers. I expect that some readers here will be annoyed, for different reasons, and I wouldn’t write the article quite this way for a different audience (I would have qualified some points, and emphasized others, for example), but I don’t see any reason to change the basic argument.

Repost over the fold.

At the recent American Economic Association meeting in San Diego, Brad DeLong chaired a panel on ” Stimulus or Stymied?: The Macroeconomics of Recessions“, and has posted a transcript. Paul Krugman was there and picked up my claim that macroeconomics has, on balance, gone backwards since 1958. I’ve extracted his section here. Lots of useful stuff, but I’d stress this:

the whole basis on which we constructed monetary policy during the Great Moderation, which is that stabilizing inflation and stabilizing output are the same thing, is all wrong: you can have a sustained period of low but not negative inflation consistent with an economy operating far below its potential productive capacity. That is what I believe is happening now. If so, we are failing dismally in responding to this economic crisis. This is in contrast to what some central bankers are saying—that we have done well because inflation has stayed relatively stable.

To push this a bit further, I’d argue that there will be no real recovery as long as central banks continue to treat the inflation-targeting polices of the (spurious) Great Moderation as the pre-crisis normal to which we should strive to return

Roger Farmer, professor of economics at UCLA, has sent a response to my post on the fiscal multiplier, which is over the fold. I’ll make some substantive points in comments, but I’d like to start by saying that this is a good example of a discussion to which blogs are ideally suited. Contributions from people like Roger who have something important to say, but not the time or inclination for a regular blog, make it even better.

Much of the recent discussion in the “state of macroeconomics” has concerned the question

* Is macroeconomics making progress?

* If not, when did it stop?

I’m not going to survey the whole debate, but I will point to a good contribution from Robert Gordon (linked by JW Mason in comments to a previous post). Gordon argues that 1978-era New Keynesian macro is better than the DSGE approach dominant today. That implies 30 years of retrogression.

My own view is even more pessimistic. On balance, I think macroeconomics has gone backwards since the discovery of the Phillips curve in 1958 [1][2]. The subsequent 50+ years has been a history of mistakes, overcorrection and partial countercorrections. To be sure, quite a lot has been learned, but as far as policy is concerned, even more has been forgotten. The result is that lots of economists are now making claims that would have been considered absurd, even by pre-Keynesian economists like Irving Fisher.

The biggest theoretical issue in macroeconomics is “what causes unemployment”. As discussed in the last post, the classical answer, that unemployment is caused by problems in labor markets, is obviously wrong as an explanation of the simultaneous emergence of sustained high unemployment in many different countries. Unemployment is a macroeconomic problem.

The central macroeconomic policy issue, then, is “what, if anything, can macroeconomic policy do to move the economy back to full employment”. If you accept that, under current conditions of zero interest rates, there’s not much positive that can be done with monetary policy[1], and you stay within the bounds of mainstream policy debate, this question can be restated as “how effective is expansionary fiscal policy” or, in Keynesian terms, “how large is the fiscal multiplier in a depression”.

Following up my previous post, I want to look at the main areas of disagreement in macroeconomics. As well as trying to cover the issues, I’ll be making the point that the (mainstream) economics profession is so radically divided on these issues that any idea of a consensus, or even of disagreement within a broadly accepted analytical framework, is nonsense. The fact that, despite these radical disagreements, many specialists in macroeconomics don’t see a problem is, itself, part of the problem.

I’ll start with the central issue of macroeconomics, unemployment. It’s the central issue because macroeconomics begins with Keynes’ claim that a market economy can stay for substantial periods, in a situation of high unemployment and excess supply in all markets. If this claim is false, as argued by both classical and New Classical economists, then there is no need for a separate field of macroeconomics – everything can and should be derived from (standard neoclassical) microeconomics.

When econbloggers aren’t arguing about cyborgs, they spend a fair bit of time arguing about the state of (mainstream) macroeconomics[1], that is, the analysis of aggregate employment and unemployment, inflation and economic growth. Noah Smith has a summary of what’s been said, which I won’t recapitulate. Instead, I’ll give my take on some of the issues that have been raised (what follows is inevitably monkish wonkish)

I just love econobloggers, with their capacity for Swiftian satire. Dry as dust, yet clearly having a laugh, they aim to reel in the poor saps who are take them seriously, but they are big enough to continue to play along, making as if they really mean it. Until now, I’d thought of Tyler Cowen, Bryan Caplan and, perhaps, even Arnold Kling as being the true masters of the genre. But I’m pretty sure that Noah Smith surpasses them all with a new blog on The Rise of the Cyborgs. Smith does a really excellent job of pretending to be keen on the robot-human future he imagines. So, for example, we get

artificial eyes and ears would replace all input devices [i.e. actual eyes and ears]. You would never need a television screen, a phone, Google Goggles, or a speaker of any kind. All you would need would be your own artificial eyes. You could play video games in perfect, pure augmented reality. Imagine the possibilities for video-conferencing, or hanging out with friends half a world away! And why stop there? If you wanted, you could perceive the buildings around you as castles, or the inside of a spaceship. The whole world could look and sound however you wanted.

But understandably, he feigns enthusiasm most successfully about the prospects for the economy:

… cyborg technologies have the potential to improve human productivity quite a bit, as my examples above have hopefully shown. Humans who can store vast amounts of knowledge and expertise, who can directly interface with machines, and who can make themselves more well-adjusted and motivated at the touch of a (mental) button will be valuable employees indeed, and will prove useful complements to the much-discussed army of robots.

Indeed, employers could make it a condition of employment that workers undergo the necessary cyber-modifications! Actually, I think Smith missed a trick there, by failing to imagine how this might affect workplace dynamics. Oh well, I expect someone will be along to explain how such contracts would be win-win. Brilliant.

Last month’s issue of Boston Review has a very good essay by James Heckman, and follow-up discussion. Heckman’s essay argues forcefully for early childhood interventions of various kinds as efficient means for mitigating inequality of opportunity.

I’d especially recommend that you read Charles Murray’s comment, just so you can read Heckman’s (devastating) response, but also Annette Lareau’s and David Deming’s. And, if you want, mine and Swift’s.

One thing I am curious about. Heckman is consistently accused by lefties of not understanding that poverty, not parenting, is the fundamental problem. For all I know that is true, and it is not impossible that I have a tin ear, but when I read his essay (and hear him talk etc) everything he says is consistent with the (entirely reasonable) assumption that as things stand, though the fundamental problem may well be poverty, elected officials are pretty determined to do very little to reduce poverty in general and child poverty in particular, so we need to look for policy levers that would improve the prospects of poor children without addressing their poverty. (And, if by some chance, this pessimistic assessment is wrong, still the measures he proposes would play an important role during the long transition to a more equal society). Is it just because he is known to be, broadly speaking, a conservative that people read him the less charitable way? Or am I, indeed, missing something?

That’s the headline for a piece I published in The National Interest last week. Opening paras

Among the unchallenged verities of U.S. politics, the most universally accepted is that of the crucial strategic and economic significance of oil, and particularly Middle Eastern oil. On the right, the need for oil is seen as justifying an expanded and assertive military posture, as well as the removal of restrictions on domestic drilling. On the left, U.S. foreign-policy is seen through the prism of “War for Oil,” while the specter of Peak Oil threatens to bring the whole system down in ruins.

The prosaic reality is that oil is a commodity much like any other. As with every major commodity, oil markets have some special features that affect supply, demand and prices. But oil is no more special or critical than coal, gas or metals—let alone food.

This piece expands on my earlier argument that the US has no national interest at stake in the Middle East, just a set of mutually inconsistent sectional interests and policy agendas. I don’t talk about climate change explicitly, but we’ll never have a sensible debate about climate change until oil is demystified.