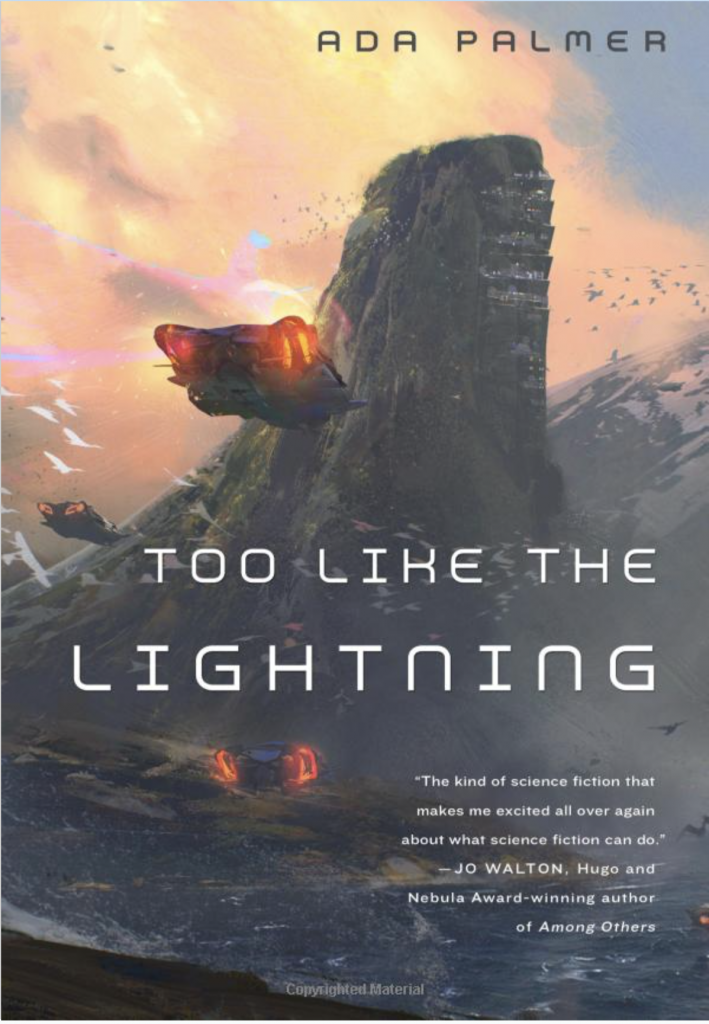

Ada Palmer’s Too Like the Lightning is finally out (Powells, Amazon), so that you can read it too (I’ve been impatiently waiting to share it with everyone I know). As Jo Walton says here, it’s wonderful. It does something that I think is genuinely new (or at least, if other people have pulled it off, I haven’t read them). Palmer is a historian (here’s an interview I did with her on her book about Lucretius’ reception in the Renaissance) and approaches science fiction in a novel way. Her 25th century draws on the ideas of Enlightenment humanism, but in the same ways that, say, America draws on the writers of the Declaration of Independence and the Federalist Papers. Which is to say that it takes the bits that seem useful, reinterprets them or misinterprets them as new circumstances dictate, and grafts them onto what is already there, throwing away the rest. Palmer does this quite thoroughly and comprehensively – her imagined society is both thrown together in the way that real societies are, and clinker-built (in the sense that she has evidently really thought through how this would be related to that and what it might mean). [click to continue…]

From the category archives:

Intellects vast and warm and sympathetic

Via Cosma, this, by Rachel Barney at the University of Toronto, is the best thing I’ve read on the Internets in quite a while. UPDATE: since it has been Creative Commonsed, as I should have spotted immediately, am publishing the whole below the fold, free to all finders, birds, beasts, Elves or Men, and all kindly creatures.

That trolling is a shameful thing, and that no one of sense would accept to be called ‘troll’, all are agreed; but what trolling is, and how many its species are, and whether there is an excellence of the troll, is unclear. And indeed trolling is said in many ways; for some call ‘troll’ anyone who is abusive on the internet, but this is only the disagreeable person, or in newspaper comments the angry old man. And the one who disagrees loudly on the blog on each occasion is a lover of controversy, or an attention-seeker. And none of these is the troll, or perhaps some are of a mixed type; for there is no art in what they do. (Whether it is possible to troll one’s own blog is unclear; for the one who poses divisive questions seems only to seek controversy, and to do so openly; and this is not trolling but rather a kind of clickbait.)

Well then, the troll in the proper sense is one who speaks to a community and as being part of the community; only he is not part of it, but opposed. And the community has some good in common, and this the troll must know, and what things promote and destroy it: for he seeks to destroy. Hence no one would troll the remotest Mysian, or even know how, but rather a Republican trolls a Democratic blog and a Democrat Republicans. And he destroys the thread by disputing what is known to be true, or abusing what is recognised as admirable; or he creates fear about a small problem, as if it were large, or treats a necessary matter as small; or he speaks abuse while claiming to be a friend. And in general the troll says what is false but sounds like the truth—or rather he does not quite say it, but rather something very close to it which is true, or partly true, or best of all merely asks a simple question about the evidence for climate change. Hence the modes of trolling are many: the concern-troll, the one who ‘sees the other side’, the polite inquirer into the obvious. For the perfected troll has no need of rudeness or abuse, or even of fallacy (this belongs rather to sophistic or eristic, and requires making an argument): he only makes a suggestion or indication [sêmainein]. [click to continue…]

I’m reading Russell Muirhead, The Promise of Party In A Polarized Age: [click to continue…]

Since the dawn of time, man has wondered: what are p-values? [click to continue…]

First things first: thanks to everyone who dug deep (or shallow) to purchase (or just freely download) a copy of Reason and Persuasion, allowing us to enjoy evanescent ecstasies of semi-upward-mobility into the 5-digit sales range on Amazon for a period of some days now. Now please keep that Amazon aspidistra flying for the next several years running and we’ll have ourselves a standard textbook! (Sigh. I know. No hope. If I want sales like that, I have to update Facebook more than once every 4 years. And be on Twitter. Shudder.)

As I was saying: it is also fun to watch the (no doubt CT-fueled) evolution of the ‘customers who viewed this item also viewed’ Amazon scrollbar, associating our Plato book with all manner of comics and science fiction. I hope the present post shall further enrich that eclectic mix.

Back in December I posted about how I would like a history of semi-popular philosophy of mind, to complement the history of science fiction. Many people left genuinely useful, interesting comments, for which I am sincerely grateful. Today I would like to strike out along a semi-parallel line. Science fiction film, with its special effects, has a strong phenotypic and genotypic relation to stage magic. Georges Méliès was a stage magician. But sf is older than film; stage magic, too. We might enhance our sense of the modern origins of the former by coordinating with the modern history of the latter. I just read a good little book, Conjuring Science: A History of Scientific Entertainment and Stage Magic in Modern France, by Sofia Lachappelle, that doesn’t make the sf connection, but makes it easy to make. (It’s an overpriced good little book, I’m sorry to say. Oh, academic publishing. But perhaps you, like me, enjoy library privileges somewhere.)

It contains some nice sentences, certainly. For example: “While Robertson was presenting his phantasmagoria in an abandoned convent and professors of amusing physics were performing their wonders, scientific and technological innovations were impacting the world of the theater at large.” (118)

As I was saying: history of modern stage magic. I’ll quote passages, and comment, and supplement with relevant images. [click to continue…]

Whew! My Dreher post comments are running kind of long. Clearly, Crooked Timber needs fresh content. OK, I just realized that two things I’ve been thinking about this week – Rod Dreher’s Ben-Op plans, and Franklin Booth’s pen-and-ink style – are kind of the same. Franklin Booth? Via Lines and Colors, I found this nice page of fairly high-quality scans. This sort of stuff (click for larger):

That’s pen-and-ink, because Booth was trying … well, I’ll just let Wikipedia explain:

His unusual technique was the result of a misunderstanding: Booth scrupulously copied magazine illustrations which he thought were pen-and-ink drawings. In fact, they were wood engravings. As a result, this led him to develop a style of drawing composed of thousands of lines, whose careful positioning next to one another produced variations in density and shade. The characteristics of his art were his scale extremes with large buildings and forests looming over tiny figures, decorative scrolls and borders, classic hand lettering and gnarled trees.

“Poor David Bowie. Barely 72 hours dead and he’s already being misremembered.”

I like the URL. “david-bowie-transgender-1970s-misappropriated?” I think probably the piece was written on a bet, and the URL reflects that.

No, seriously. The piece follows the standard template for conservative kulturkampf tu quoque. It’s by-the-numbers. But there is a purity to it.

Obituary here (via Tyler Cowen). He was a fascinating and very important writer and thinker, although his final two books were not as strong as his earlier work. The politics of his ideas are complicated – on the one hand moving away from the efficiency arguments of markets towards political processes of institutional formation, but on the other never precisely able to decide whether and when these political institutions were guided by a logic of lowering transaction costs or by the desire of powerful actors to reap distributional benefits. Path dependence in his work serves more as a stand-in for an explanation than an explanation in its own right, especially given the continuing question (not really resolved in his work or the work of those he influenced) as to why some economies (by his account) changed and began to develop towards the rule of law while others did not. Still, even if he didn’t explain this, no-one else has done an especially good job either. One thing that is likely to get overlooked in his work is his continued engagement with the left. The first time I had had a serious conversation with him, he described himself as a “Marxist of the right,” which seems correct to me (I’m pretty sure I’m not the only person he used this self-description with). There’s a good essay to be written on his encounter with Karl Polanyi – this essay (PDF) disagreeing with Polanyi contains the seeds of some of his most crucial arguments. He will be missed.

In addition to teaching Nietzsche, I’m teaching Science Fiction and Philosophy. (Yes, I lead a charmed life.)

One of the fun games hereabouts is digging up cases in which old philosophical texts anticipate sf tropes or terms. Plato’s Cave, Descartes’ demon, Leibniz’ thinking mill. You get the idea.

Here are two slightly less well-known examples from Mill. The first, from Chapter 3 of On Liberty: [click to continue…]

So the MacArthur ‘genius’ awards were announced today; I’ve always thought of them as tottering on a Bourdieuian knife-edge between two different kinds of legitimation. On the one hand, they are supposed to have consequences, to publicly recognize people who would otherwise be less well known, and giving them financial and symbolic support that they can then go on to use to do good and wonderful things. This means that it would be weird to give one e.g. to someone like Paul Krugman, who already is doing very nicely in terms of public recognition. On the other, they are supposed to go to people who are creative and brilliant – but in socially legitimated ways so as to maintain the status of the award. This means that they are unlikely to go to genuinely unsung geniuses, not simply because the selection process can’t find brilliance if it isn’t publicly well known, but because the legitimacy of the awards partly depends on their social validation by a variety of elite networks.

Hence, for example, we get today’s decision to give an award to Ta-Nehisi Coates. In one sense this is unquestionably awesome – Coates is fantastic. However, it would be unquestionably much more awesomer if they had given an award to Coates five years before, or gave it today to someone where Coates was five years ago. But the sociology of the process doesn’t seem to be set up to do that – like most institutions, it gravitates towards safe choices. A more risky symbolic venture capital approach – say giving grants to people earlier in their career in the expectation that 80% of them will flame out, 10% will do well, and 10% will be just wonderful would probably not be sustainable over the longer term (or at the least, it would make the prizes very different in status and connotation). Hence the current set up, which I suspect is mostly aimed to support safe bets – people who are either famous or very well regarded in their specific discipline – with perhaps a couple of riskier ones thrown in here and there, where they really strike fire with one of the selectors.

So if we were giving out awards rather than the actual selection committee, who would we give them to? It’s not likely, but it is possible that actual real people involved in the selection process will read this (Crooked Timber doesn’t have Vox-level readership, but it does have its own odd forms of cultural capital; stranger things have happened). So it’s possible that this thread could have consequences. Comments are open. My own two nominees (I can think of other very deserving candidates, but they’re personal friends; I’m also sure I’ll kick myself about all the people I should have mentioned as soon as I’ve posted this) would be Astra Taylor and Tom Slee. Both are writers in the hinterlands between technology and culture, neither is so high profile as to be a likely candidate at the moment. But both are just fantastic – brilliant writers (and in Taylor’s case, documentary maker and musician too) who could do wonderful things with MacArthur level exposure. Who else?

I spent a good chunk of yesterday reading the second half of Lynsey Addario’s [*It’s What I Do: A Photographer’s Life of Love and War*](http://itswhatidobook.com/). I’d been reading it a few pages at a time for the previous week, but then I just got carried away and had to read right to the end. As CT readers know, I’m keenly interested in photography, but it is also the case that reading accounts from war photographers (and seeing their pictures) has changed the way I think about war and conflict.

After September 11th 2001, the blogosphere erupted into being a thing, and several hundred part-time pundits spent a good period of their time arguing with one another about Afghanistan, Iraq, the Islamic world, military tactics and a thousand other things they knew virtually nothing about. Some of them are typing still. I penned what I now regard as an unfortunate essay on just war theory and Afghanistan, unfortunate because there I was applying abstract principles to conflicts where I hadn’t a clue about the human reality. I hope I’d be more careful and less reductive today, and that’s partly as a result of people like the photographer Don McCullin, and his autobiography *Unreasonable Behaviour*. I’d heard of Addario’s book a few months ago, but then I saw some of her pictures at a festival of documentary photography in Perpignan, France, and decided I had to read it.

[click to continue…]

Having made one recent post that topped 1000 comments, I thought I would try to be more abstruse for a time.

I have a trivia question for you. I’m reading Volney’s The Ruins. Why? Because it’s one of the books that Frankenstein’s monster overhears: [click to continue…]

I wasn’t paying attention to un-approved comments in the queue, so a bunch got stuck there. Why? Because I almost never do anything about them until a co-blogger is like, “hey Belle, remember how we have a moderation queue that ever requires you to do a thing ever?” I just went and approved them all, as is generally my inclination, even–I will have you know–the ones calling me a bad person who writes in a fundamentally unserious way about serious subjects, and who is personal friends with Brad DeLong even though he is an economic quisling and opinionatedly wrong about works of history about Eastern Europe which I (myself, Belle Waring) have not read. So, if it seemed as if you were in moderation hell, sorry about that.

You also really have to work at it to get me to ban you; please don’t. It’s tedious. I wouldn’t do it even if I personally disagreed with you about historiography of Eastern Europe, rather than at a trusted remove (at which remove I also won’t ban you obvi, since, here you are). Well, if I knew you were fabricating lies and hurling spurious claims of ‘anti-Semite’ everywhere I’d hassle you, but you’d have to be King Dick of it to get banned on my account. I did have some homophobia in the first thread from whoever it is who has been baiting MPAVictoria so incessantly. It was fake homophobia that he wasn’t even selling. I wasn’t buying a nickel bag of it. But pretending to be bigoted is almost worse. I seriously am too bored to look up his very-like-another-person’s name right now. You, thingface, knock it off, and MPAV for the love of all that is unholy just don’t rise snapping to that hand-tied-fly what has been cast onto the mottled surface of our limpen stream. And then…a male commenter said this to me:

[click to continue…]

I’m glad to have spread the gorey news regarding Daumier. Some commenters were evidently unfamiliar. Here’s a nice Flickr set if you just want to browse. But, for CT’s especially philosophically-minded and discerning readership, one from Daumier’s “Histoire Ancienne” series. (It also belongs in my collection of philosophers looking silly. This one is also good.)

I present: Socrates doing a soft cancan, to Aspasia’s discomfort. [click to continue…]