The third and final instalment of my critique of Locke’s theory of appropriation/expropriation is up at Jacobin. I turn my attention from Locke to Jefferson, Locke’s most important follower, in practice as well as theory. By opening the Louisiana purchase for agricultural settlement, Jefferson put to the test Locke’s theory of appropriation to a practical test. In particular, the vastness of the land, compared with the modest requirements of the ideal Jeffersonian farm family seemed to support Jefferson’s prediction that the new land would be enough to last a thousand generations. But of course the opposite was true: in less than one generation, the United States had overspilled the boundaries of Jefferson’s purchase and was embroiled in a civil war that started with battles over the newly opened land. To restate the conclusion of the previous instalments, Locke’s theory was designed to justify expropriation and enslavement. Neither Locke nor epigones such as Nozick and Rothbard can provide a coherent theory of just appropriation of property.

In the hopes that everyone will stop commenting on Corey’s post, hence at considerable risk to myself: a fresh Trump post.

Since becoming aware of this thing called ‘US politics’, some decades ago, I have been addicted to the consumption of punditry. I don’t say it with pride, or because I suppose it makes me special. I just thought I’d mention that one thing that makes Trump’s candidacy weird – in a phenomenological sense, I guess – is that there is no pro-Trump pundit class. This makes his candidacy inaudible along one of the frequencies I habitually tune in. By and large, I can’t go to NR or The Weekly Standard or Red State, much less Ross Douthat or National Affairs, to get pretzel logic confabulations on Trump’s behalf, because they actually haven’t gotten on board. To their credit. Twitter is a snarknado of negative partisanship. Breitbart and Drudge are entropically dire, in a Shannon-informational sense. Hugh Hewitt? Nixonian party loyalist. He’s defending Trump the way he defended Harriet Miers, i.e. it really has nothing to do with the quality of the candidate. The only Trumpkins comfortable in their skins are the alt-right folks, reveling in rather than regretting the fact that Trump is constantly escaping from the Overton Straitjacket; and pick-up artists who regard Trump’s alpha male posturing as a feature, not a diagnosis. Oh, and there’s Scott Adams. “The fun part is that we can see cognitive dissonance when it happens to others – such as with my friend, and CNN – but we can’t see it when it happens to us. So don’t get too smug about this. You’re probably next.” Duly noted. [click to continue…]

{ 62 comments }

Another Kierkegaard post, then! The masses are clamoring for them, demanding this sweet release from ongoing Olympic coverage! Also, Trump!

19th Century European philosophy. Does it crack along the 1848 faultline, after which Hegel is dead? Not sure but maybe. In addition, many of the main figures are odd men out – Kierkegaard, Nietzsche (and I like Schopenhauer, too.) Hegel was huge but his stock collapsed. He went from hero to zero and later figures like Frege, whom analytic philosophers sometimes suppose must have been opposed to Hegel, just didn’t give him much thought. (Frege was worried about Lotze, i.e. neo-Kantianism, not Hegel. The notion that analytic philosophy opposes Hegel is a kind of anachronistic back-formation of Russell and Moore’s opposition to the likes of McTaggart, i.e. the Scottish Hegelians, who were their own thing. But I digress.) Philosophy in general had a fallen rep in the second half of the 19th century, at least in German-speaking regions. Also in France? An age of positivism? Natural science was what you wanted to be doing, not speculative nonsense. There is a strong regionalism. German stuff in the 19th Century is very German. The Romantics. (Whereas, in the 17th Century, the Frenchness of Descartes, the Germanness of Leibniz, the Englishness of Locke, even the Jewishness of Spinoza seem less formidable obstacles to mutual comprehension. I am broad-brushing, not dismissing historical digs into this stuff. Tell me I’m wrong! It won’t hurt my feelings.)

Kierkegaard is not the lone wolf Nietzsche will be later, but he’s a regional figure. Part of the Copenhagen scene, the Danish Golden Age. Nordic literary culture, tied into German culture and French culture, too, but distinctive and somewhat self-contained. So I’m asking myself: what are good historical handles? And I think: maybe read some Georg Brandes? He was very influenced by Kierkegaard, at the end of a passionate Hegelian fling in youth. He gave the first public lectures on Nietzsche, at a time when he – Brandes – was personally famous, a towering figure in criticism. He was responsible for Nietzsche’s fame, in effect. (Is that too strong?) He also traveled to England, met J.S. Mill, after translating The Subjection of Women into Danish.

I was very much surprised when Mill informed me that he had not read a line of Hegel, either in the original or in translation, and regarded the entire Hegelian philosophy as sterile and empty sophistry. I mentally confronted this with the opinion of the man at the Copenhagen University who knew the history of philosophy best, my teacher, Hans Bröchner, who knew, so to speak, nothing of contemporary English and French philosophy, and did not think them worth studying. I came to the conclusion that here was a task for one who understood the thinkers of the two directions, who did not mutually understand one another.

I thought that in philosophy, too, I knew what I wanted, and saw a road open in front of me. However, I never travelled it. (276-7, Reminiscences of My Childhood and Youth)

Yet there’s a lot of philosophical interest in his books. (You can get a number for free from the Internet Archive, as they were all translated into English in the early 20th Century, when Brandes was at the height of his fame.) [click to continue…]

{ 11 comments }

I’ve always been of the ‘McCartney is tooooo sweet’ school, though I’m aware he has tried to recapture that “Helter Skelter” grit and growl periodically down the years. Well, I just discovered his 2008 Fireman album, Electric Arguments, which is a terrible name for an album, which got some critical attention at the time but I missed it. I think a few tracks are pretty darn great. Beefheart-y beefiness, even if Paul’s pipes were built to shine at the high end. He isn’t exactly Howlin’ Wolf. But the boy can sing. Track 1 [click to continue…]

{ 11 comments }

I wrote a survey article on “Caricature and Comics” for The Routledge Companion To Comics. (I’m sorry to say that the volume is currently very overpriced, although I trust in a few years they will release a more modestly-priced paperpack version, and the Kindle version price shall descend from the heavens, where it dwells.) However, Routledge allows authors to self-archive, so I did. Abstract:

Caricature and comics are elastic categories. This essay treats caricature not as a type or aspect of comics but as a window through which we can view comics in relation to the broader European visual art tradition. Caricature is exaggeration. But all art exaggerates, insofar as it stylizes. Is all art caricature, since all has ‘style’? Ernst Gombrich’s classic Art and Illusion comes close to arguing so. This article conjoins critical reflections on Gombrich’s discussion of ‘the experiment of caricature’ with a survey of art historical paradigm cases. It makes sense for comics to emerge from this mix.

And this seems like a nice occasion to showcase the newest addition to my small, but growing set of philosophical caricatures. Soren Kierkegaard!

{ 6 comments }

There’s nothing like a few unexpected days at home to allow you to discover new things, and the great find of the past few days — thanks to a tweet from Fernando Sdrigotti @f_sd — has been to watch (via Youtube, start [here](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vpijOSSlZCI) five programmes in all) some BBC documentaries about Albert Kahn and his Archives of the Planet, now preserved at the [Musée Albert Kahn](http://albert-kahn.hauts-de-seine.fr/) outside Paris. Born in Alsace, Kahn was displaced by the Prussian seizure of the territory in 1871 and became immensely rich though banking and investing in diamonds. But he was also an idealist, convinced that if the various tribes of humanity only knew one another better they would empathize more and would be less likely to go to war. In pursuit of this hope, and taking advantage of the Lumière Brothers’ [Autochrome](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autochrome_Lumi%C3%A8re) colour process, he sent teams of photographers to all parts of the globe and, before the First World War, caught many forms of life on the edge of being swept away by globalisation, war and revolution. (There’s quite a good selection [here](http://www.afar.com/magazine/a-trip-through-time) but google away.) Pictures taken around the Balkans, for example, depict the immense variety of different cultures living side-by-side at the time and then later we see the sad stream of refugees from the second Balkan War as they head from Salonika towards Turkey. Kahn’s operative document rural life in Galway, harsh penal regimes in Mongolia, elite life in Japan and a tranquil Rio de Janeiro with little traffic and few people.

Kahn’s hope for a peaceful world was lost in 1914, but we owe to his project many images of wartime France, particularly the life of ordinary people behind the lines. Postwar, Kahn was a great supporter of the League of Nations and, again, his operatives were on hand to document many of the upheavals of the inter-war years, such as the burning of Smyrna in 1922 (as Izmir, the city is once again crowded with refugees today) and the abortive attempt to found the Rhenish Republic in 1923. Many of the photographs are included in a book by David Okuefuna, *The Wonderful World of Albert Kahn: Colour Photographs from a Lost Age* (BBC Books, 2008). Sadly, Kahn was ruined by the Great Depression and died in Paris shorly after the Germans invaded in 1940. He seems little-known today, but there’s a lot of material out there that’s worth your time.

{ 12 comments }

The Guardian today [publishes a vast number of leaked reports from Nauru](https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/aug/10/the-nauru-files-2000-leaked-reports-reveal-scale-of-abuse-of-children-in-australian-offshore-detention), one of Australia’s offshore processing sites for asylum-seekers (in reality, a camp for the indefinite detention of asylum-seekers). The reports, or “unconfirmed allegations” as the Australian government would have it, are a harrowing catalogue of physical and sexual abuse, and of consequences for mental and bodily well-being, often suffered by children. These places exist to appease an Australian citizenry hostile to the arrival of “boat people” who believe that such people — even those determined to be refugees by Convention criteria — are not their problem. Though Nauru is a particularly vile example, it would be wrong to think that Australians are alone in their attitudes to refugees and asylum seekers. Other Western governments are happy to do deals with other states beyond their borders to ensure that the wretched of the earth are out of sight, where they can exist as an abstraction, not disturbing the conscience of their own citizens. Human rights, together with other liberal principles like the rule of law, have become, for many liberal democratic states, the exclusive right of the native-born citizen or, at best, someone else’s problem, somewhere else.

I’d be interested to learn from people in Australia now, how much traction this latest leak is getting in the Australian media. A surf to the websites of the Australian and the Sydney Morning Herald suggests not much.

{ 26 comments }

Last night, I had a bout of insomnia. So I picked up the latest issue of Vanity Fair, and after reading a rather desultory piece by Robert Gottlieb on his experiences editing Lauren Bacall (who I’m distantly related to), Irene Selznick, and Katharine Hepburn (boy, did he not like Hepburn!), I settled down with a long piece by Sam Tanenhaus on William Styron and his Confessions of Nat Turner.

A confession of my own first: I read Confessions sometime in graduate school. I loved it. Probably my favorite work by Styron, much more so than Sophie’s Choice or even Darkness Visible. I say “confession” because it’s a book that has had an enormously controversial afterlife, which Tanenhaus discusses with great sensitivity, even poignancy.

Anyway, I recommend Tanenhaus’s article for a variety of reasons: great narrative pace, with that perfect balance of distance and engagement; it blows hot and cold exactly where and when you need it to; and it moves with an almost symphonic sense of time, back and forth across the decades and centuries.

But here are three things IÂ wanted to comment on. [click to continue…]

{ 12 comments }

My old poker buddy Eric Schwitzgebel has, for some time, been soliciting Top-10 lists from folks who teach SF and philosophy. So I finally got around to contributing. Tell me I’m wrong!

Eric has busted into sf authorship himself since our grad school days. Here’s one of his in Clarkesworld, “Fishdance”. “The two most addictive ideas in history, religion and video-gaming, would finally become one.” It’s good!

One thing I’m going to talk about this semester is the domestication of experience machines. In genre terms, The Matrix is a bit played out. Inception. Been there, done that. Can we agree about that? Also, video games just get normaler and normaler. Yesterday I looked around on the train and I was, literally, the only person NOT playing “Pokemon Go”. True story! It felt a bit weird. They were all off together in an alternate version of the city. I was alone in the real one, with only my headphones and music to keep me warm – like some savage. There are two obvious ways to make virtual life, as an alternative to real life, appealing: make the world really messed up. Make the virtual world nice. Maybe the people behind the scenes don’t need to be Agent Smith-style jerks. The first film to play it this way, in a nice way, is Avalon. But no one saw it. Good film. More recently you get the likes of Ready Player One and Off To Be The Wizard, in which players of games – and games within games, and games within games within games – are increasingly comfortable with the whole biz. Not that there’s no lingering anxiety about the appropriateness of this life strategy! I like to think that one of my all time faves, The Glass Bead Game, is an honored ancestor. Homo Ludens. What’s Latin for ‘man, the player of virtual reality games’?

Of course, I think of myself as more of a cartoonist than an sf author. Since I’m on the subject, here are a couple graphics I whipped up for my module last time, which amused me – although I did it all fast-and-sketchy. I’d really like to remake them carefully, in a Norman Saunders-y style.

The idea is to make fake pulp covers for classic scientific and philosophical thought-experiments. [click to continue…]

{ 28 comments }

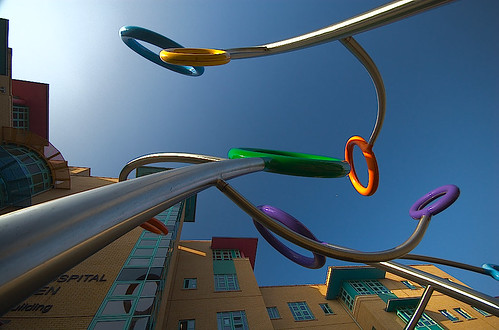

This week’s picture is quite an old one, of the sculpture outside the then-new Bristol Children’s Hospital which is directly adjacent to the Bristol Royal Infirmary, where I spent a good past of the last week following an acute gallstone attack (with associated pancreatitis) last weekend. On the Thursday I had my gall bladder removed (which turned out to be slightly more complicated than anticipated) and by Friday I was home. I’m now resting and recuperating, but basically feeling fine. Some reflections on the experience below the fold.

[click to continue…]

{ 13 comments }

I’ve been getting lots of free books lately, and the implied contract is that I should write about at least some of them. So, here are my quick reactions to some books CT readers might find interesting. They are

The Great Leveler: Capitalism and Competition in the Court of Law by Brett Christophers

The Rise and Fall of American Growth:

The U.S. Standard of Living since the Civil War by Robert J. Gordon

The Sharing Economy:The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism by Arun Sundararajan

Econobabble: How to Decode Political Spin and Economic Nonsense by Richard Denniss

Generation Less: How Australia is Cheating the Young by Jennifer Rayner

I’ll be on a panel discussing the last two of these at the Brisbane Writers Festival, Sep 11-16.

{ 7 comments }

As I believe I have mentioned, I’m teaching Kierkegaard. K is an excellently – some say inordinately – literary-aesthetical sort of fellow, so we want to welcome that quality, when we invite him to come give a talk to our class. But there comes a stage in man’s life when he wearies of undergraduates writing yet another paper about Fight Club and/or The Matrix, or even “The Grand Inquisitor” from Dostoyevsky. More broadly, there is an academic convention – who knows when it got started? – of nudging the young into equating a work of philosophy to a work of literature/art, i.e. pretending the latter is likely to be, let alone was intended to be, a vehicle for the expression of the former. And so it turns out Hamlet was Shakespeare’s ham-handed attempt to write an essay on Freud, or what have you. These attempted equations invite minor (or major) fraud. (Not that I think this is a major social problem. Mostly it’s just silly and strained.) And for what? You can fit things to things without exaggerating the degree of fit. (Kierkegaard was a weirdo. What are the odds any literary figure, who wasn’t K, ever produced a Kierkegaardian work of literary fiction? Hell, even K had to pretend he wasn’t himself, half the time, to keep from falling into error about his author’s meaning.)

I’m thinking of assigning a few short works that are, to my eye, not Kierkegaardian. But one can make connections, draw lines. For example, Lord Dunsany’s “The Kith of the Elf-Folk”. Here we have spheres of existence, I guess you could say: aesthetic, religious – ethical? (Now we are pushing it.) And there is a nice question, twinkling in the author’s eye: which is higher? How could one be in a position to say? And there is an implied indictment of modern society (who could wish for less?) And there is a lyrical seriousness, yet ironic playfulness. So the question I’m going to ask the kids is: suppose you had to rewrite “The Kith of the Elf-Folk” to be a parable of Kierkegaard’s stages – which it plainly is not. What changes would you have to make? Defend your adaptive edits!

Or maybe that’s a really, really bad question that will produce bad results in my classroom.

But my question for you is a bit different. How great is this story? Pretty great, right? [click to continue…]

{ 51 comments }

In a recent post, I remarked on the fact that hardly any self-described climate sceptics had revised their views in response to the recent years of record-breaking global temperatures. Defending his fellow “sceptics”, commenter Cassander wrote

When’s the last time you changed your mind as a result of the evidence? It’s not something people do very often.

I’m tempted by the one-word response “Derp“. But the dangers of holding to a position regardless of the evidence are particularly severe for academics approaching emeritus age[1]. So, I gave the question a bit of thought.

Here are three issues on which I’ve changed my mind over different periods

* Central planning

* War and the use of violence in politics

* The best response to climate change

[click to continue…]

{ 86 comments }

Having posted about Gaus’ new book, let me link to Will Wilkinson’s review essay at Vox. Will is more enthused about the conclusions than I am, although I agree it’s a great read. I’ve been trying to work out my own thoughts in the same vicinity and, for post purposes, I’ll just sketch a thumbnail argument that seems to me the right Gaus-style indictment of Rawls, using a modified version of his mountain metaphor. [click to continue…]

{ 50 comments }