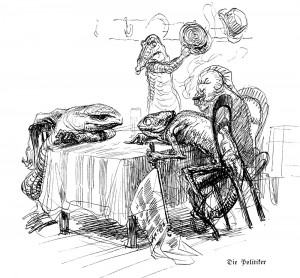

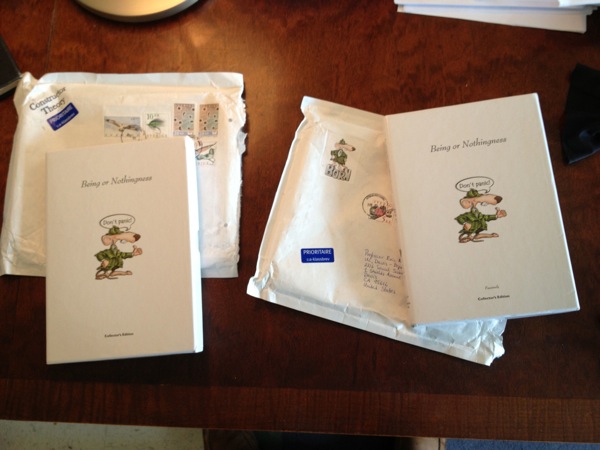

I was going to review a couple of new books I picked up – The Lost Art of Heinrich Kley, Volume 1: Drawings & Volume 2: Paintings & Sketches

. (Those are Amazon links. You can get it a bit cheaper from the publisher. And see a nifty little video while you’re there.) But now I seem to have lost vol. 1 of Lost Art. Turned the house over, top to bottom. Can’t find it anywhere! Oh, well. Bottom line: I’ve been collecting old Kley books for a while. It’s fantastic stuff – if you like this kind of stuff – and these new books contain a wealth of material I had never seen. I wish, I wish the print quality in vol. 1 were higher because the linework really needs to pop. The color stuff in volume 2 is better, and harder to come by before now. One editorial slip. Kley’s Virgil illustrations come from a ‘travestiert’ Aeneid, by Alois Blumauer, not a ‘translated’ one. Parody stuff. (There, I just had to get my drop of picky, picky pedantry in there.) That said, the editorial matter in both volumes is extremely interesting. Volume 2 has a great Intro by Alexander Kunkel and a very discerning little Appreciation by Jesse Hamm, full of shrewd speculations about Kley’s methods. He’s a bit of a mystery, Kley is.

The books are in a Lost Art series that is clearly a labor of love for Joseph Procopio, the editor.

In honor of our Real Utopias event, I’ll just give you Kley on politics and metaphysics. (These particular images aren’t from these new volumes, but they’re nice, aren’t they?)

Click for larger.