Its been a busy couple of weeks — we were on vacation sort of, and then catching up. It is wonderful to me that Wisconsin 2011 I learned of Sarah-Jane’s death from a bunch of 14 year olds I’d just made a really good dinner for. But I’d rather it weren’t true. Barry Letts, the Brig, and now Sarah Jane, its been a tough couple of years.

Grauniad obit here.

Choice quote: ‘Current producer Steven Moffat said: “Never meet your heroes, wise people say. They weren’t thinking of Lis Sladen.”‘

{ 5 comments }

In Australia it’s the evening of May Day, though as it falls on a Sunday we will (in Queensland at least[1]) celebrate it with that great Australian institution, a long weekend. Last year, I went on the march, this year I ran a triathlon instead[2]. My somewhat confused attitude is, I think, pretty characteristic of the position labour movement more generally.

Updated below

[click to continue…]

{ 34 comments }

Here’s some commentary on the Canadian general election from CT’s good friend up north, Tom Slee.

From Boring to Bizarre: Canada Votes 2011

For the second election in a row, Canada’s trip to the polls has, to use a technical term, gone weird. The big story this time round is the rise of the perennial third- or fourth-place New Democratic Party, making NDP leader Jack Layton the probable leader of the opposition and possibly even Prime Minister – something no one (and I mean NO ONE) would have believed possible three weeks ago. I was reluctant to accept Henry’s invitation to comment here because there are many people who know more about Canadian electoral politics than I do, but as NO ONE else had a clue this was going to happen either, it might as well be me to open the comment thread.

For any of you not completely up to date, here’s what’s been happening (note to self – switch to present tense here for that sports-commentator-like sense of immediacy):

- March 25: Stephen Harper’s minority Conservative government loses a no-confidence vote that found the government in contempt of parliament. (CBC report)

- March 27: The six-week campaign officially opens. The Conservatives attack Liberal leader Michael Ignatieff relentlessly for being too little Canadian (“He didn’t come back for you”) and too much academic (Harvard for God’s sake), but no issue catches fire with the public.

- April 12 and 13: The mid-campaign TV debates are held, one in English and then one in French. The French debate was moved forward a day so as not to clash with a hockey game. There is no big moment, no immediate announcement of a winner.

- Over the next few days, the NDP starts to pick up support from the Bloc Quebecois, despite never having a significant showing in that province.

- Around Easter, the Liberal vote starts to bleed to the NDP and support for the Grits falls from high 20s to low 20s, and all of a sudden the NDP has almost doubled its share from 17% up to about 30%, clearly in second place (see Andrew Heard’s page at Simon Frasier University, or ThreeHundredEight.com). The Google Trends results for the party leaders summarize the campaign as well as anything.

Which all raises two questions. What caused these dramatic shifts? And what happens next?

Causes first. The leaders are all known quantities; the policy platforms are basically the same as in the 2008 and 2006 elections; the Canadian economy was insulated from the worst of the financial collapse by a combination of oil and good fortune in its banking history; no political or economic issue has taken hold during the campaign. What gives?

It may be worth remembering that it’s the second time in a row that a Canadian election has gone from boring to bizarre. Back in 2008 the Liberals called an election and, then as now, everyone knew that the election would conclude with everything looking the same as before. The Bloc Quebecois would hold on to 50 or so seats in Quebec. The Tories, now a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Alberta-based Reform Party, were too socially conservative and too doctrinaire to make a breakthrough in seat-rich Ontario and would be limited to about 100 seats from the western provinces, the Liberals would get pretty much all of Ontario’s 100 seats plus some from the maritimes, and the NDP would stay at 20 or so seats. But Liberal leader Paul Martin stumbled and was labelled as “Mister Dithers”, the label stuck and the Tories took 40 seats in Ontario, enough to form a minority government. Once the Liberals started losing support, everything just went from bad to worse for them.

All I can see is that the self-referential nature of recent campaigns, in which poll results themselves have become the major daily news item, lends itself to wild and unpredictable fluctuations as voters’ opinions are shaped by their perceptions of the trends around the country. The patterns remind me of the Salganik, Dodds, and Watts studies of artifical cultural markets from a few years ago (PDF): social decision making leads to cascade-driven inequalities in outcomes, but the outcome is only obvious once you know the answer.

Despite talk of this being Canada’s first social media campaign, I think it’s uncontroversial to say that social media has had little impact. There has been publicity for student “vote mobs” and some questions about the legality of tweeting on election night (before the polls close in the west), but basically the campaign has been mass-media driven.

And as for what happens next? Well who the hell knows. The big questions are whether the NDP polling results will hold up and, in a country with strong regional distinctions, how the nationwide trends will be reflected at the level of individual ridings. It could be that the NDP surge leads to a majority conservative government, or it could be that an NDP-led coalition of the non-right will end up taking power, or it could be… well what? I look to commenters to tell us.

As for me, for the last few elections I have been actively involved in the local NDP campaign, and in 2008 that ended with the Conservatives winning over the Liberals by 17 votes; the closest race in the country. I have never previously considered tactical voting, but this time I have signed up at Pair Vote as my choice is strongly Anyone But Harper. I’d like to think it’s the right thing to do, but with this campaign, who knows?

{ 186 comments }

Well, now, seems like it’s about time for me to revisit <a href=”https://crookedtimber.org/2011/04/12/winter-sports-roundup/”>my predictions for the first round of the NHL playoffs (Eastern Conference)</a>, and … my stars, what do you know? My new method of choosing teams by way of citing random passages from experimental literary texts has proven to be spectacularly successful! To recap:

<b>Me</b>:

Caps in 5

Flyers in 6

Bruins in 7

Lightning in 6

<b>Reality</b>:

Caps in 5

Flyers in 7

Bruins in 7

Lightning in 7

I think this pretty much proves that <a href=”https://crookedtimber.org/2011/04/25/parents-can-rid-campuses-of-communists/#comment-356456″>Dreyfus was guilty.</a>

[click to continue…]

{ 22 comments }

On Twitter yesterday, “Daniel Davies asked”:http://twitter.com/dsquareddigest/status/63004206600167424,

bq. If AV is so god damned simple, why can nobody explain convincingly to me whether it screws the LibDems or not?

This seems like a fun question to work through at longer than Twitter length, even if it is purely hypothetical, since the No side “is going to win”:http://ukpollingreport.co.uk/blog/archives/3504.

One obvious answer is that as long as the “Liberal Democrats are polling 10%”:http://ukpollingreport.co.uk/blog/archives/3507 the voting system won’t make a lot of difference. Another obvious answer is that if the Lib Dems recover at all, then AV would seem to help them. There will be plenty of seats, such as “Oxford East”:http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/shared/election2010/results/constituency/d47.stm which they lost under FPTP, but would have a very good chance of winning under AV.

But if AV in England[1] plays out in a similar way to how AV played out in Australia, there is a big risk to the Lib Dems. They could lose a huge portion of their vote to the Greens.

{ 252 comments }

No-one will be fooled. I demand the White House release video of Obama being born on home plate during the 1961 World Series, with Roger Maris attending the delivery and being heard to remark “That’s a fine-looking future President you have there, Ann”. Oh wait, is the White House REFUSING to release this video? Or maybe—just maybe—are they in fact UNABLE TO? And why do you think that would be? Because the so-called President was IN AFRICA at the time? Because Hawaii wasn’t even a U.S. Territory in 1961? I think you can join the dots yourself. I rest my case.

{ 58 comments }

Bristol had a riot last Thursday night. I wasn’t there, although I’ve spoken to a number of people who were or who observed events from windows overlooking the action. The facts are still not entirely clear, but becoming clearer. As far as I can establish them they are:

Beyond this the facts are murky.

{ 50 comments }

John Quiggin and I have a “piece”:http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/67761/henry-farrell-and-john-quiggin/how-to-save-the-euro-and-the-eu on the eurozone mess in the new issue of _Foreign Affairs._ The piece is subscriber-only, but we’re allowed to post it (in Web format) for six months or so on a personal or institutional website. Accordingly, the piece can be found below the fold. The piece was finished some weeks ago, but I think it holds up quite well.

Four things worth noting. First – I suspect we would put our argument that the politics are more important than the economics even more strongly in the light of current events. It looks as though demonstrations against the austerity agenda are beginning to take on a European dimension. In addition, a dimension of the politics that we did not discuss – the rise of nationalist resentments in countries that are on the giving rather than receiving end of loans-linked-to-brutalism – has come more obviously to the fore with the success of the True Finns in the recent election.

Second – Paul de Grauwe has a “new paper”:http://www.econ.kuleuven.be/ew/academic/intecon/Degrauwe/PDG-papers/Discussion_papers/Governance-fragile-eurozone_s.pdf which points to a complementary mechanism through which monetary union plausibly damages political legitimacy at the national level (although his discussion is largely framed in terms of the economics).

bq. Once in a bad equilibrium, members of monetary union find it very difficult to use automatic budget stabilizers: A recession leads to higher government budget deficits; this in turn leads to distrust of markets in the capacity of governments to service their future debt, triggering a liquidity and solvency crisis; the latter then forces them to institute austerity programs in the midst of a recession.

Third: the Daniel Davies qualification. We refer to BIS data on bank holdings in the article – but as we specifically note (and as dsquared has pointed out in comments here and elsewhere), this data is biased by tax avoidance wheezes and similar. It is plausible to infer that e.g. German banks have some considerable exposure to PIIGS from the way that they are behaving, and the numbers are the best that there is, but they should be treated with caution.

Finally – the piece is written in the rhetorical style of US policy articles. This differs from that of blogposts and academic articles, in that it encourages emphatic claims rather than cautions and caveats, and self-assurance rather than social-scientific humility. Please read accordingly.

{ 190 comments }

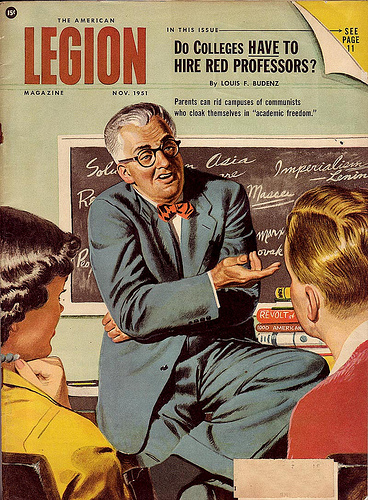

These days the bow tie signifies the opposite, of course. Which only shows their disguises have improved.

{ 228 comments }

Matthew Yglesias points to this Arthur Brooks piece, “Obama says it’s only ‘fair’ to raise taxes on the rich. He’s wrong.” Brooks says he’s shifting from the usual perverse consequences argument – if we tax the rich it will actually cost more money – to a fairness argument. But really it’s just a twistier iteration of the perverse consequences argument.

Basically the first part of the argument goes like this. [click to continue…]

{ 176 comments }

Here is a very old joke. A soldier is captured during a long-running war and thrown into the most stereotypical prison cell imaginable. Inside the cell is another solider. He has an enormous, disgusting-smelling beard and has clearly been there a long time. The young solider immediately sets about trying to escape. He is resourceful and possessed of great willpower. He bribes a guard with his emergency supply of cash. The guard gets him into a supply truck and he makes it to the prison garage, but is found during a routine vehicle search while exiting the compound. He is returned to his cell. His mangy companion says nothing about his departure or return. Undeterred, the young soldier works on the bars of the cell for weeks, filing them down with a shim made from a toothbrush. The whole time the old soldier looks on, silently. The young soldier finally breaks the bars, slips out the window and makes it to the outer wall, where he is spotted and recaptured. He is thrown back in the cell. He glowers at his grizzled companion, who still remains silent. Calming himself and mastering his despair, he tries yet again, this time digging a tunnel with the narrow end of a broken plastic coffee spoon. After about two years of work he succeeds in escaping under the wall and making it to the nearest town, only to be captured again at the train station. He is delivered, once again, back to his cell and its taciturn occupant. At the end of his wits, the young soldier finally confronts the old soldier, shouting, “Couldn’t you at least offer to help me with this?! I mean, I’ve come up with all these great plans—you could have joined me in executing them! What’s wrong with you?” The old soldier looks at him and says, “Oh I tried all these methods years ago—bribery, the bars, a tunnel, and a few others besides—none of them work.” The young soldier looks at him, incredulous, and screams “Well if you knew they didn’t work, WHY THE FUCK DIDN’T YOU TELL ME BEFORE I TRIED THEM, YOU BASTARD?!” The old soldier scratches his filthy beard and says, “Hey, who publishes negative results?“

{ 20 comments }

And so the year rolls around yet again to Krauthammer Day, the day on which we all celebrate Charles Krauthammer’s “confident assertion”:http://www.aei.org/event/274 eight years ago that:

bq. Hans Blix had five months to find weapons. He found nothing. We’ve had five weeks. Come back to me in five months. If we haven’t found any, we will have a credibility problem.

Or _nearly_ all of us celebrate it anyway. Charles Krauthammer himself seems to prefer to mark the occasion with an entirely unrelated “Run, Paul Ryan Run!”:http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-racing-form-2012/2011/04/21/AFT4TxKE_story.html?hpid=z2 column. Which is a little sad – after all it has been five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus five months plus thirty days or so since he first put his, and his friends’ credibility on the line. It would be nice to see him (and others) mark the occasion more formally.

Perhaps the problem is that we have never _fixed on exactly how_ to celebrate Charles Krauthammer Day. Easter, Christmas, Hannukah, Festivus etc all have their associated and time-honored rituals, but Krauthammer day has none. Combining suggestions from “George W. Bush”:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jA2q00caZsY&feature=related and “Hugh Hector Munro”:http://haytom.us/showarticle.php?id=31, one possibility might be an Exploding Easter Egg Hunt. But then, this would perhaps prove simultaneously too dangerous to be very attractive to participants, and not dangerous enough to really mark the occasion properly. Better suggestions invited in comments.

Update: On the basis of a genuinely insane reading of this post, the execrable Glenn Reynolds gravely “deplores”:http://pajamasmedia.com/instapundit/119106/ my incivility. I don’t read Reynolds these days, for all the obvious reasons, but have quite clear and unfond memories of his own contributions to civil conversaton back in his heyday, such as this “denunciation of Chris Hedges”:http://www.pajamasmedia.com/instapundit-archive/archives/009671.php as a ‘flat-out racist’ for suggesting that Iraq was likely to be a ‘cesspool’ for the US invasion. How this claim comported with his “approving quote of a correspondent”:http://www.pajamasmedia.com/instapundit-archive/archives2/2006/11/post_21.php a couple of years later, arguing that

bq. The ball is in the Iraqis’ court. We took away the obstacle to their freedom. If they choose to embrace death, corruption, incompetence, lethal religious mania, and stone-age tribalism, then at least we’ll finally know the limitations of the people in that part of the world. The experiment had to be made.

and his own conclusion that:

bq. On the other hand, it’s also true that if democracy can’t work in Iraq, then we should probably adopt a “more rubble, less trouble” approach to other countries in the region that threaten us. If a comparatively wealthy and secular Arab country can’t make it as a democratic republic, then what hope is there for places that are less wealthy, or less secular?

has always been a mystery to me. The only plausible way in which Reynolds could have been promoting the cause of civil conversation here was by helpfully denouncing himself in advance as a ‘flat out racist’ so that right minded people could know not to associate themselves with him. Perhaps there’s another explanation – but if so, he has as best I know (as I say I don’t read him these days) been shy about advancing it.

{ 87 comments }

Kevin Drum posts a fun screed against it. I didn’t know the experimental evidence was so damning, although I’m not surprised. But I am surprised that there is little consideration of what I would have thought was an obvious, major category of multitasking, going back to the Peripatetic School: engaging something with your mind while doing something unrelated, and probably repetitive, with your other muscles. Reading a book while riding the stationary bike. Playing scales or exercises on your instrument, over and over, while listening to the news. What about plain old reading a book while listening to music?

Drum links to an interview that rules this out, definitionally: “Multitasking as we’re studying it here involves looking at multiple media at the same time. So we’re not talking about people watching the kids and cooking and stuff like that. We’re talking about using information, multiple sources.” And there may be a music exception. Maybe we have a special module for that.

Fine, define terms how you like. But this seems misleading, because ‘task’ naturally covers cooking and kid-watching. [click to continue…]

{ 57 comments }

Because of the day that’s in it, here’s a simple Aperture Science Keynote Theme. The theme requires you have Univers installed. For maximum effectiveness, the use of this theme is best accompanied by a well-prepared text, a clear speaking voice, and—for fielding questions—a functional Aperture Science military android. I’ll probably use the theme in class tomorrow (though the turret is still being shipped to me). Here are some samples:

[click to continue…]

{ 12 comments }

I’ve been meaning to respond to this “very interesting Tom Slee post”:http://whimsley.typepad.com/whimsley/2011/03/blogs-and-bullets-breaking-down-social-media.html for weeks and weeks.

bq. Maybe we should stop talking about “information and communication technologies” or “the Internet” or “new and social media” as a single constellation of technologies that have key characteristics in common (distinctively participatory, or distinctively intrusive, for example), and that are sufficiently different from other parts of the world that they need to be talked about separately. The Internet is still pretty new, so we tend to look at it as a definable thing, but digital technologies have now become so multifaceted and so enmeshed in other facets of our lives that such a broad brush obscures more than it reveals.

[click to continue…]

{ 31 comments }